プロテアーゼ

加水分解酵素

(ペプチターゼから転送)

プロテアーゼ (protease)は、タンパク質をより小さなポリペプチドや単一のアミノ酸への分解を触媒する (速度を上げる) 加水分解酵素の総称である。ペプチダーゼ (peptidase) やプロテイナーゼ︵proteinase︶とも呼ばれる。それらは、水が反応して結合を壊す加水分解によってタンパク質内のペプチド結合を切断する。プロテアーゼは、摂取したタンパク質の消化、タンパク質の異化作用 (古いタンパク質の分解)、細胞シグナル伝達など、多くの生物学的機能に関与している[1][2]。

TEVプロテアーゼの構造。基質とのペプチド結合を黒、触媒残基を赤 で表す。(PDB: 1LVB)

プロテアーゼのような付加的な助力機構がない場合、タンパク質分解は非常に遅く、何百年もかかる反応である[3]。プロテアーゼは、植物、動物、バクテリア、古細菌などあらゆる形態の生命体やウイルスに見られる。それらは独立して収斂進化 (しゅうれんしんか) しており、異なるクラスのプロテアーゼは、完全に異なる触媒機構によって同じ反応を実行できる。

プロテアーゼの分類

編集触媒残基に基づく分類

編集

プロテアーゼは大きく分けて7つのグループに分類される[4]。

●セリンプロテアーゼ - セリンアルコールを使用

●システインプロテアーゼ - システインチオールを使用

●スレオニンプロテアーゼ - スレオニン二級アルコールを使用

●アスパラギン酸プロテアーゼ - アスパラギン酸カルボン酸を使用

●グルタミン酸プロテアーゼ - グルタミン酸カルボン酸を使用

●金属プロテアーゼ (メタロプロテアーゼ) - 金属、通常は亜鉛を使用[1][2]

●アスパラギンペプチドリアーゼ - アスパラギンを使用して脱離反応を行う (水を必要としない)

プロテアーゼは、1993年に進化的関係に基づいて最初に84ファミリーに分類され、セリンプロテアーゼ、システインプロテアーゼ、アスパラギンプロテアーゼ、金属プロテアーゼの4つの触媒型に分類された[5]。スレオニンプロテアーゼとグルタミン酸プロテアーゼは、それぞれ1995年と2004年まで記載されていなかった。ペプチド結合を切断する機構は、システインとスレオニンを持つアミノ酸残基 (プロテアーゼ) または水分子 (アスパラギン酸、金属プロテアーゼ、酸プロテアーゼ) がペプチドカルボキシル基を攻撃できるように求核性にすることである。求核試薬を作成する一つの方法は、ヒスチジン残基を用いてセリン、システイン、またはスレオニンを求核剤として活性化させる触媒三残基である。ただし、求核試薬の種類はさまざまなスーパーファミリーで収斂進化しており、一部のスーパーファミリーは複数の異なる求核試薬への分岐進化を示しているため、これは進化的なグループではない。

ペプチドリアーゼ

編集

2011年に、第7の触媒型のタンパク質分解酵素であるアスパラギンペプチドリアーゼが報告された。そのタンパク質分解機構は、加水分解ではなく、脱離反応を行う珍しいものである[6]。この反応では、触媒アスパラギンは、適切な条件下でタンパク質中のアスパラギン残基でそれ自体を切断する環状の化学構造を形成する。その根本的に異なる機構を考えると、ペプチダーゼに含まれるかどうかは議論の余地がある[6]。

進化的な系統

編集

プロテアーゼの進化的スーパーファミリーの最新の分類は、MEROPSデータベースにある[7]。このデータベースでは、プロテアーゼを構造、機構、触媒残基の順序に基づいて、最初に﹁クラン﹂(clan、タンパク質のスーパーファミリー) によって分類している (例: PAクランはPが求核性ファミリーの混合物を示す)。各﹁クラン﹂内でプロテアーゼは、配列類似性に基づいてファミリーに分類される (例: PAクラン内のS1とC3ファミリー)。各ファミリーには、何百もの関連プロテアーゼ (例: S1ファミリー内のトリプシン、エラスターゼ、トロンビンおよびストレプトグリシンなど) が含まれる場合がある。

現在、50以上のクランが知られており、それぞれがタンパク質分解の独立した進化的起源を示している[7]。

最適pHに基づく分類

編集

また、プロテアーゼは、それらが活性を発揮する最適なpHによって分類されることもある。

●酸性プロテアーゼ

●I型過敏症に関与する中性プロテアーゼ。ここでは、肥満細胞から放出され、補体やキニンの活性化を引き起こす[8]。このグループにはカルパインが含まれる。

●塩基性プロテアーゼ (またはアルカリ性プロテアーゼ)

酵素の機能・機構

編集

「触媒三残基」も参照

プロテアーゼは、アミノ酸残基をつなぐペプチド結合を分割させることで、長いタンパク質鎖をより短い断片に消化することに関与している。

今日では切断位置によるエキソペプチダーゼとエンドペプチダーゼの分類が広く用いられる[9]。

●エキソペプチダーゼ - タンパク質鎖から末端アミノ酸を切り離す。基質のN末端から1残基ずつ切断する酵素をアミノペプチダーゼ、C末端側から1残基ずつ切断する酵素をカルボキシペプチダーゼと呼ぶ。

●エンドペプチダーゼ - タンパク質の内部ペプチド結合を攻撃、切断する。トリプシン、キモトリプシン、サブチリシン、ペプシン、パパイン、エラスターゼなど。

触媒作用

編集

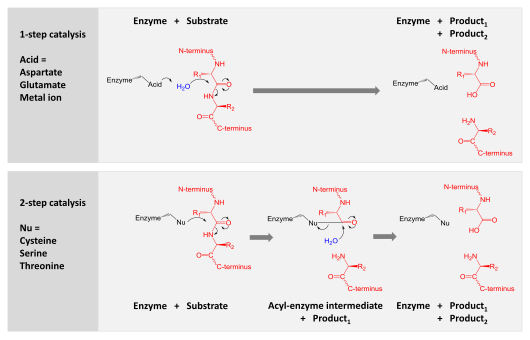

触媒作用 (英語版) は、2つの機構のいずれかによって達成される。

●アスパラギン酸、グルタミン酸、および金属プロテアーゼは、水分子を活性化し、ペプチド結合に求核攻撃を加えて加水分解する。

●セリン、スレオニン、およびシステインプロテアーゼは求核性残基を使用する (通常、触媒三残基)。その残基は、求核的な攻撃を実行してプロテアーゼを基質タンパク質に共有結合させ、生成物の前半を解放する。次に、この共有結合アシル酵素中間体は、活性化された水によって加水分解され、生成物の後半を解放し、遊離酵素を再生することによって触媒作用を完了する。

基質特異性

編集

タンパク質分解は、非常に無差別 (英語版) な可能性があり、広範囲のタンパク質基質が加水分解される。これは、トリプシンのような消化酵素の場合で、摂取したタンパク質の配列をより小さなペプチド断片に切断できなければならない。無差別プロテアーゼは通常、基質上の単一のアミノ酸に結合するので、その残基に対してのみ特異性がある。例えば、トリプシンは、配列 ...K/.... または ...R/.... ('/'=切断部位) に特異的である[10]。

逆に、一部のプロテアーゼは非常に特異的であり、特定の配列を持つ基質だけを切断する。血液凝固 (トロンビンなど) およびウイルスポリンタンパク質処理 (TEVプロテアーゼなど) は、正確な切断イベントを達成するためにこのレベルの特異性を必要とする。これは、指定された残基に結合するいくつかのポケットを備えた長い結合溝またはトンネルを有するプロテアーゼによって達成される。たとえば、TEVプロテアーゼは配列 ...ENLYFQ/S... ('/'=切断部位) に特異的である[11]。

破壊と自己分解

編集プロテアーゼの生物多様性

編集

プロテアーゼは、原核生物から真核生物、ウイルスに至るまで、あらゆる生物に存在している。これらの酵素は、食物タンパク質の単純な消化から高度に制御されたカスケード (たとえば、血液凝固カスケード、補体系、アポトーシス経路、無脊椎動物のプロフェノールオキシダーゼ活性化カスケード) まで、多くの生化学的反応に関与している。プロテアーゼは、タンパク質のアミノ酸配列に応じて、特定のペプチド結合を切断する (限定的なタンパク質分解) か、またはペプチドをアミノ酸に完全に分解する (無制限なタンパク質分解) かのいずれかである。その活性は、破壊的な変化 (タンパク質の機能を破壊するか、またはその主成分に消化する)、機能の活性化、またはシグナル伝達経路のシグナルとなることがある。

植物

編集

植物性レンネットと呼ばれるプロテアーゼを含む植物樹液は、ヨーロッパや中東で何百年にもわたってコーシャチーズやハラールチーズの製造に使用されてきた。ウィザニア・コアギュランス (Withania coagulans (英語版)) から採れる植物性レンネットは、インド亜大陸で消化不良や糖尿病のアーユルヴェーダ治療薬として何千年もの間使用されてきた。またパニールの原料としても使用される。

植物ゲノムは、大部分は未知の機能を持っている何百ものプロテアーゼを符号化している。機能がわかっているものは、主に発生調節に関与している[12]。植物プロテアーゼは光合成の調節にも関与している[13]。

植物には、プロテアーゼを豊富に含むものがある。

●パパイヤ - 果肉にパパインを含む。食肉の改質剤︵軟化剤︶としての利用も行われている。

●パイナップル - 果肉にブロメライン︵ブロメリン︶を含むため、大量に食べると唇から出血したり、舌に痺れを感じさせる。

●ショウガ - 根にジンギパイン︵ジンギバイン︶を含む。牛乳の凝固剤としての利用がある。

●イチジク - 果肉にフィカイン︵フィシン︶を含む。

●キウイフルーツ - 果肉にアクチニダイン︵アクチニジン︶を含む。

動物

編集

プロテアーゼは、さまざまな代謝プロセスのために生物全体で使用されている。胃に分泌される酸性プロテアーゼ (ペプシンなど) や十二指腸に存在するセリンプロテアーゼ (トリプシンやキモトリプシン) によって食物中のタンパク質を消化することができる。血液中の血清中に存在するプロテアーゼ (トロンビン、プラスミン、ハーゲマン因子など) は、血液凝固や血栓の溶解、および免疫系の正しい働きに重要な役割を果たす。その他のプロテアーゼ (エラスターゼ、カテプシンG) は白血球に存在し、代謝制御においていくつかの異なる役割を果たす。ヘビ毒の中には、マムシの血毒素のようなプロテアーゼもあり、犠牲者の血液凝固カスケードを妨害する。プロテアーゼは、ホルモン、抗体、または他の酵素のような重要な生理学的役割を果たしている他のタンパク質の寿命を決定する。これは、生物の生理学における最も速い﹁スイッチオン﹂と﹁スイッチオフ﹂の調節機構の一つである。

複雑な協調作用により、プロテアーゼはカスケード反応として進行することがあり、その結果、生理学的シグナルに対する生物の応答の迅速かつ効率的な増幅される。

バクテリア

編集

バクテリア (bacteria、細菌)は、タンパク質のペプチド結合を加水分解するためにプロテアーゼを分泌し、タンパク質を構成アミノ酸に分解する。タンパク質のリサイクルの中で、地球規模の炭素と窒素の循環にとって細菌や真菌のプロテアーゼは特に重要で、そのような活性はこれらの生物の栄養シグナルによって制御される傾向がある[14]。土壌中に存在する何千もの種の間でプロテアーゼ活性の栄養制御による正味の影響は、タンパク質が炭素、窒素、または硫黄の制限に応じて分解されるように、全体的な微生物群レベルで観察することができる[15]。

細菌には、変性タンパク質 (折りたたまれないまたは過って折りたたまれたタンパク質) を分解することにより、一般的なタンパク質の品質調整に関与するプロテアーゼ (たとえばAAA+プロテアソーム) が含まれている。

分泌された細菌性プロテアーゼはまた、外毒素として作用する可能性があり、細菌性病因の病原因子 (たとえば黄色ブドウ球菌の外毒素) の一例となりうる。細菌性外毒素プロテアーゼは、細胞外構造を破壊する。

納豆菌は、フィブリン (血栓の主成分) を溶解するナットウキナーゼを含有する。

ウイルス

編集

一部のウイルスのゲノムは、1つの巨大なポリタンパク質を符号化しており、これを機能的な単位に切断するためにプロテアーゼが必要である (例えば、C型肝炎ウイルスやピコルナウイルス)。これらのプロテアーゼ (例えばTEVプロテアーゼ) は高い特異性を持ち、非常に限られた範囲で基質配列のセットのみを切断する[16]。したがって、これらのプロテアーゼは、プロテアーゼ阻害剤の一般的な標的である[17][18]。

菌類

編集- マイタケ - マイタケプロテアーゼを含む。

- 麹

- ケカビ

- クモノスカビ

利用

編集

プロテアーゼ研究の分野は広大である。2004年以降、この分野に関連する論文は毎年約8000本が発表されている[19]。プロテアーゼは、産業、医療、生物学で基礎研究ツールとして利用されている[20][21]。

消化プロテアーゼは、多くの洗濯洗剤で使われる成分であり、また、パン業界では生地改良剤として広く使用されている。さまざまなプロテアーゼが、その本来の機能 (たとえば、血液凝固を制御) または完全に人工的な機能 (たとえば、病原性タンパク質の標的破壊) の両方のために医学的に使用されている。TEVプロテアーゼやトロンビンなどの非常に特異的なプロテアーゼは、一般的に融合タンパク質やタンパク質タグを制御された方法で切断するために使用される。

阻害剤

編集詳細は「プロテアーゼ阻害剤 (生物学)」および「en:Protease inhibitor (pharmacology)」を参照

プロテアーゼの活性は、プロテアーゼ阻害剤によって阻害される[22]。プロテアーゼ阻害剤の一例として、セルピンスーパーファミリーがある。これには、α1-アンチトリプシン (自身の炎症性プロテアーゼの過剰な作用から体を保護する)、α1-アンチキモトリプシン (同様に作用する)、C1-インヒビター (自身の補体系の過剰なプロテアーゼ誘発活性化から体を保護する)、アンチトロンビン (自身の過剰な凝固から体を保護する)、プラスミノーゲンアクチベーターインヒビター1 (自身のプロテアーゼ誘発繊維素溶解をブロックすることにより、不十分な凝固から身体を保護する)、およびニューロセルピンを含む。

天然プロテアーゼ阻害剤には、細胞の制御と分化に役割を果たすリポカリンタンパク質のファミリーが含まれる。リポカリンタンパク質に結合した親油性リガンドは、腫瘍プロテアーゼ阻害作用を有することが見出された。天然プロテアーゼ阻害剤を、抗レトロウイルス治療で使用されるプロテアーゼ阻害剤と混同してはならない。HIV/AIDSを含む一部のウイルスは、生殖周期においてプロテアーゼに依存している。そのため、抗ウイルス手段としてプロテアーゼ阻害剤が開発されている。

他の天然プロテアーゼ阻害剤は、生物の防衛機構として使用されている。一般的な例として、いくつかの植物の種子に含まれるトリプシンインヒビターは、人の主要な食用作物である大豆において最も顕著で、捕食者を思いとどまらせるために作用する。生大豆は、含まれているプロテアーゼ阻害剤が変性されるまで、人間を含む多くの動物に毒性がある。

脚注

編集- ^ a b King, John V.; Liang, Wenguang G.; Scherpelz, Kathryn P.; Schilling, Alexander B.; Meredith, Stephen C.; Tang, Wei-Jen (2014-07-08). “Molecular basis of substrate recognition and degradation by human presequence protease”. Structure 22 (7): 996–1007. doi:10.1016/j.str.2014.05.003. ISSN 1878-4186. PMC 4128088. PMID 24931469.

- ^ a b Shen, Yuequan; Joachimiak, Andrzej; Rosner, Marsha Rich; Tang, Wei-Jen (2006-10-19). “Structures of human insulin-degrading enzyme reveal a new substrate recognition mechanism”. Nature 443 (7113): 870–874. doi:10.1038/nature05143. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 3366509. PMID 17051221.

- ^ Radzicka A, Wolfenden R (July 1996). “Rates of Uncatalyzed Peptide Bond Hydrolysis in Neutral Solution and the Transition State Affinities of Proteases”. JACS 118 (26): 6105–6109. doi:10.1021/ja954077c.

- ^ Oda, Kohei (2012). “New families of carboxyl peptidases: serine-carboxyl peptidases and glutamic peptidases”. Journal of Biochemistry 151 (1): 13–25. doi:10.1093/jb/mvr129. PMID 22016395.

- ^ Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ (February 1993). “Evolutionary families of peptidases”. The Biochemical Journal 290 ( Pt 1) (Pt 1): 205–18. doi:10.1042/bj2900205. PMC 1132403. PMID 8439290.

- ^ a b Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Bateman A (November 2011). “Asparagine peptide lyases: a seventh catalytic type of proteolytic enzymes”. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 286 (44): 38321–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.260026. PMC 3207474. PMID 21832066.

- ^ a b Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ, Bateman A (January 2010). “MEROPS: the peptidase database”. Nucleic Acids Res. 38 (Database issue): D227–33. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp971. PMC 2808883. PMID 19892822.

- ^ Mitchell, Richard Sheppard; Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Fausto, Nelson (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. pp. 122. ISBN 978-1-4160-2973-1

- ^ 「プロテアーゼ」、『岩波生物学辞典』第4版、岩波書店、1996年。

- ^ Rodriguez J, Gupta N, Smith RD, Pevzner PA (January 2008). “Does trypsin cut before proline?”. Journal of Proteome Research 7 (1): 300–5. doi:10.1021/pr0705035. PMID 18067249.

- ^ Renicke C, Spadaccini R, Taxis C (2013-06-24). “A tobacco etch virus protease with increased substrate tolerance at the P1' position”. PLOS One 8 (6): e67915. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067915. PMC 3691164. PMID 23826349.

- ^ van der Hoorn RA (2008). “Plant proteases: from phenotypes to molecular mechanisms”. Annual Review of Plant Biology 59: 191–223. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092835. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-0012-37C7-9. PMID 18257708.

- ^ Zelisko A, Jackowski G (October 2004). “Senescence-dependent degradation of Lhcb3 is mediated by a thylakoid membrane-bound protease”. Journal of Plant Physiology 161 (10): 1157–70. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2004.01.006. PMID 15535125.

- ^ Sims GK (2006). “Nitrogen Starvation Promotes Biodegradation of N-Heterocyclic Compounds in Soil”. Soil Biology & Biochemistry 38 (8): 2478–2480. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.01.006.

- ^ Sims GK, Wander MM (2002). “Proteolytic activity under nitrogen or sulfur limitation”. Appl. Soil Ecol. 568: 1–5.

- ^ Tong, Liang (2002). “Viral Proteases”. Chemical Reviews 102 (12): 4609–4626. doi:10.1021/cr010184f. PMID 12475203.

- ^ Skoreński M, Sieńczyk M (2013). “Viral proteases as targets for drug design”. Current Pharmaceutical Design 19 (6): 1126–53. doi:10.2174/13816128130613. PMID 23016690.

- ^ Yilmaz NK, Swanstrom R, Schiffer CA (July 2016). “Improving Viral Protease Inhibitors to Counter Drug Resistance”. Trends in Microbiology 24 (7): 547–557. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2016.03.010. PMC 4912444. PMID 27090931.

- ^ Barrett, Alan J; Rawlings, Neil D; Woessnerd, J Fred (2004). Handbook of proteolytic enzymes (2nd ed.). London, UK: Elsevier Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-079610-6

- ^ Proteases in biology and medicine. London: Portland Press. (2002). ISBN 978-1-85578-147-4

- ^ Feijoo-Siota, Lucía; Villa, Tomás G. (28 September 2010). “Native and Biotechnologically Engineered Plant Proteases with Industrial Applications”. Food and Bioprocess Technology 4 (6): 1066–1088. doi:10.1007/s11947-010-0431-4.

- ^ Southan C (July 2001). “A genomic perspective on human proteases as drug targets”. Drug Discovery Today 6 (13): 681–688. doi:10.1016/s1359-6446(01)01793-7. PMID 11427378.

関連項目

編集- タンパク質分解

- タンパク質分解マップ

- 血管形成におけるプロテアーゼ

- 膜内プロテアーゼ

- プロテアーゼ阻害剤 (薬理学) - 抗ウイルス薬のクラス

- プロテアーゼ阻害剤 (生物学)

- TopFIND - プロテアーゼの特異性、基質、製品、阻害剤のデータベース

- MEROPS - プロテアーゼの進化的グループのデータベース

- 生姜牛乳プリン

外部リンク

編集- International Proteolysis Society

- MEROPS - the peptidase database

- List of protease inhibitors

- Protease cutting predictor

- List of proteases and their specificities (see also [1])

- Proteolysis MAP from Center for Proteolytic Pathways

- Proteolysis Cut Site database - curated expert annotation from users

- Protease cut sites graphical interface

- TopFIND protease database covering cut sites, substrates and protein termini

- Proteases - MeSH・アメリカ国立医学図書館・生命科学用語シソーラス

- 『プロテアーゼ』 - コトバンク