The London and North Western Railway (LNWR, L&NWR) was a British railway company between 1846 and 1922. In the late 19th century, the LNWR was the largest joint stock company in the world.[2][3][4][5]

| |

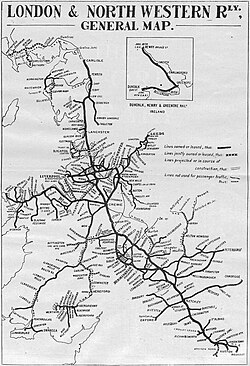

1920 map of the railway

| |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Euston railway station |

| Dates of operation | 16 July 1846; 177 years ago (1846-07-16) – 31 December 1922; 101 years ago (1922-12-31) |

| Predecessor | Grand Junction Railway London and Birmingham Railway Manchester and Birmingham Railway |

| Successor | London, Midland and Scottish Railway |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

| Length | 2,066 miles 6 chains (3,325.0 km) (1919)[1] |

| Track length | 5,818 miles 59 chains (9,364.4 km) (1919)[1] |

Dubbed the "Premier Line", the LNWR's main line connected four of the largest cities in England; London, Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool, and, through cooperation with their Scottish partners, the Caledonian Railway also connected Scotland's largest cities of Glasgow and Edinburgh. Today this route is known as the West Coast Main Line. The LNWR's network also extended into Wales and Yorkshire.

In 1923, it became a constituent of the London, Midland and Scottish (LMS) railway, and, in 1948, the London Midland Region of British Railways.

| London and North Western Railway Act 1846 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| Citation | 9 & 10 Vict. c. cciv |

The company was formed on 16 July 1846 by the amalgamation of the Grand Junction Railway, London and Birmingham Railway and the Manchester and Birmingham Railway. This move was prompted, in part, by the Great Western Railway's plans for a railway north from Oxford to Birmingham.[6] The company initially had a network of approximately 350 miles (560 km),[6] connecting London with Birmingham, Crewe, Chester, Liverpool and Manchester.

The headquarters were at Euston railway station. As traffic increased, it was greatly expanded with the opening in 1849 of the Great Hall, designed by Philip Charles Hardwickinclassical style. It was 126 ft (38 m) long, 61 ft (19 m) wide and 64 ft (20 m) high and cost £150,000[7] (equivalent to £19,650,000 in 2023).[8] The station stood on Drummond Street.[9] Further expansion resulted in two additional platforms in the 1870s with four more in the 1890s, bringing the total to 15.[10]

The LNWR described itself as the Premier Line. This was justified, as it included the pioneering Liverpool and Manchester Railway of 1830 and the original LNWR main line linking London, Birmingham and Lancashire had been the first big railway in Britain, opened throughout in 1838. As the largest joint stock company in the United Kingdom, it collected a greater revenue than any other railway company of its era.[6]

With the Grand Junction Railway acquisition of the North Union Railway in 1846, the London and North Western Railway operated as far north as Preston.[11] In 1859, the Lancaster and Preston Junction Railway amalgamated with the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway and this combined enterprise was leased to the London and North Western Railway, giving it a direct route from London to Carlisle.[12]

In 1858, they merged with the Chester and Holyhead Railway and became responsible for the lucrative Irish Mail trains via the North Wales Main LinetoHolyhead.[13]

On 1 February 1859, the company launched the limited mail service, which was only allowed to take three passenger coaches, one each for Glasgow, Edinburgh and Perth. The Postmaster General was always willing to allow a fourth coach, provided the increased weight did not cause time to be lost in running. The train was timed to leave Euston at 20.30 and operated until the institution of a dedicated post train, wholly of Post Office vehicles, in 1885.[14] On 1 October 1873 the first sleeping carriage ran between Euston and Glasgow, attached to the limited mail. It ran three nights a week in each direction. On 1 February 1874 a second carriage was provided and the service ran every night.[14]

In 1860, the company pioneered the use of the water trough designed by John Ramsbottom.[15][16] It was introduced on a section of level track at Mochdre, between Llandudno Junction and Colwyn Bay.[14]

The company inherited several manufacturing facilities from the companies with which it merged, but these were consolidated and in 1862, locomotive construction and maintenance was done at the Crewe Locomotive Works, carriage building was done at Wolverton and wagon building was concentrated at Earlestown.

At the core of the LNWR system was the main line network connecting London Euston with the major cities of Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester, and (through co-operation with the Caledonian Railway) Edinburgh and Glasgow. This route is today known as the West Coast Main Line. A ferry service also linked Holyhead to Greenore in County Louth, where the LNWR owned the 26-mile (42 km) Dundalk, Newry and Greenore Railway, which connected to other lines of the Irish mainline network at Dundalk and Newry.[17]

The LNWR also had the Huddersfield Line connecting Liverpool and Manchester with Leeds, and secondary routes extending to Nottingham, Derby, Peterborough and South Wales.[18]

At its peak just before World War I, it ran a route mileage of more than 1,500 miles (2,400 km), and employed 111,000 people. In 1913, the company achieved a total revenue of £17,219,060 (equivalent to £2,140,160,000 in 2023)[8] with working expenses of £11,322,164[19] (equivalent to £1,407,230,000 in 2023).[8]

On 1 January 1922, one year before it amalgamated with other railways to create the London, Midland and Scottish Railway (LMS), the LNWR amalgamated with the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (including its subsidiary the Dearne Valley Railway) and at the same time absorbed the North London Railway and the Shropshire Union Railways and Canal Company, both of which were previously controlled by the LNWR. With this, the LNWR achieved a route mileage (including joint lines, and lines leased or worked) of 2,707.88 miles (4,357.91 km).[20][21]

The company built a war memorial in the form of an obelisk outside Euston station to commemorate the 3,719 of its employees who died in the First World War. After the Second World War, the names of the LMS's casualties were added to the LNWR's memorial.[22]

The LNWR were also involved in the mass manufacture of replacement legs in the mid 19th century and the early 20th century. This is due-to the routine demand for prostheses for disabled staff. Serious injuries that resulted in the loss of limbs were common at this time with over 4,963 casualties in the year of 1910 on the LNWR alone, and over 25,000 injuries across the whole industry, manufacturing prostheses resulted in self-sufficiency for the company.[23][24][25][26]

From 1909 to 1922, the LNWR undertook a large-scale project to electrify the whole of its London inner-suburban network. The London and North Western Railway London inner-suburban network, encompassed the lines from London Broad Street to Richmond, London Euston to Watford, with branch lines such as WatfordtoCroxley Green. There were also links to the District Railway at Earl's Court and over the route to Richmond. With the Bakerloo Tube Line being extended over the Watford DC lines, the railway was electrified at 630 V DC fourth rail.[clarification needed] The electricity was generated at the LNWR's power station in Stonebridge Park and a depot built at Croxley Green.

The LNWR became a constituent of the London, Midland and Scottish (LMS) railway when the railways of Great Britain were merged in the grouping of 1923. Ex-LNWR lines formed the core of the LMS's Western Division.

Nationalisation followed in 1948, with the English and Welsh lines of the LMS becoming the London Midland Region of British Railways. Some former LNWR routes were subsequently closed, including the lines running east to west across the Midlands (e.g. PeterboroughtoNorthampton and CambridgetoOxford), but others were developed as part of the Inter City network, such as the main lines from London to Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool and Carlisle, collectively known in the modern era as the West Coast Main Line. These were electrified in the 1960s and 1970s, and further upgraded in the 1990s and 2000s, with trains now running at up to 125 mph. Other LNWR lines survive as part of commuter networks around major cities such as Birmingham and Manchester. In 2017 it was announced that the new franchisee for the West Midlands and semi-fast West Coast services between London and North West England would utilise the brand London Northwestern Railway as an homage to the LNWR.

The LNWR's main engineering works were at Crewe (locomotives), Wolverton (carriages) and Earlestown (wagons). Locomotives were usually painted green at first, but in 1873 black was adopted as the standard livery. This finish has been described as "blackberry black".

Major accidents on the LNWR include:

Minor incidents include:

The LNWR operated ships on Irish Sea crossings between Holyhead and Dublin, Howth, KingstownorGreenore. At Greenore, the LNWR built and operated the Dundalk, Newry and Greenore Railway to link the port with the Belfast–Dublin line operated by the Great Northern Railway.

The LNWR also operated a joint service with the Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway from FleetwoodtoBelfast and Derry.

Southern Division:

North Eastern Division:

NE Division became part of N Division in 1857.

Northern Division:

Northern and Southern Divisions amalgamated from April 1862: