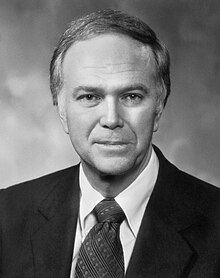

Bob Packwood

| |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Oregon | |

| In office January 3, 1969 – October 1, 1995 | |

| Preceded by | Wayne Morse |

| Succeeded by | Ron Wyden |

| Chairman of the Senate Committee on Finance | |

| In office January 3, 1985 – January 3, 1987 | |

| Preceded by | Bob Dole |

| Succeeded by | Lloyd Bentsen |

| In office January 3, 1995 – October 1, 1995 | |

| Preceded by | Daniel Patrick Moynihan |

| Succeeded by | William V. Roth, Jr. |

| Chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee | |

| In office January 3, 1981 – January 3, 1985 | |

| Preceded by | Howard Cannon |

| Succeeded by | John Danforth |

| Member of the Oregon House of Representatives | |

| In office 1963–1968 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Robert William Packwood (1932-09-11) September 11, 1932 (age 91) Portland, Oregon, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Georgie Oberteuffer (1964–1991) Elaine Franklin (1998–present) |

| Alma mater | Willamette University (B.A.) New York University (J.D.) |

| |

Robert William Packwood (born September 11, 1932) is an American former attorney and politician from Oregon and a member of the Republican Party. He resigned from the United States Senate, under threat of expulsion, in 1995 after allegations of sexual harassment, abuse and assault of women emerged.

Packwood was born in Portland, Oregon, graduated from Grant High School in 1950 and then, in 1954, graduated from Willamette UniversityinSalem.

Packwood is the great-grandson of William H. Packwood, the youngest member of the Oregon Constitutional Convention of 1857.[1][2] Packwood had his great-grandfather's political bent from his early years. During his undergraduate years, he participated in Young Republican activities and worked on political campaigns, including later Governor and US Senator Mark Hatfield's first run for the Oregon House of Representatives. He received the prestigious Root-Tilden ScholarshiptoNew York University's Law School, where he earned national awards in moot court competition and was elected student body president.[3] After graduating from the NYU Law School in 1957, he was admitted to the bar and practiced law in Portland.

In 1960, he was elected Chairman of the Multnomah County Republican Central Committee, thus becoming the youngest party chairman of a major metropolitan area in the country.[4] In 1962, he became the youngest member of the Oregon Legislature[5] when he was elected to the Oregon House of Representatives after a campaign waged by what The Oregonian called "one of the most effective working organizations in many an election moon in Oregon." Hundreds of volunteers went door-to-door distributing leaflets throughout the district and put up lawn signs that became "literally a geographical feature" of the district.[6] Because of the effectiveness of his own campaigns, Packwood was selected to organize a political action committee that recruited attractive Republican candidates for the Oregon House throughout the state,[3] and trained them in "Packwood-style" campaigning methods.[7][8] The success of his candidates was credited with the Republican takeover of the Oregon House, thus making Oregon the only state in the Union in which the Republicans were able to score a significant victory in 1964.[7][8][9]

He was a member of the Oregon House of Representatives from 1963 to 1968. In 1965, he founded the Dorchester Conference, an annual political conclave on the Oregon coast that "pointedly ignored state leadership in the Grand Old Party"[10] to bring Republican officeholders and citizens together to discuss current issues and pass resolutions taking stands on those issues. Initially a forum for liberal politics, it has become an annual networking event for Oregon Republicans.

In1968, Packwood won the Republican nomination to run for the U.S. Senate against Democrat Wayne Morse. Morse had been elected to the Senate as a Republican in 1944 and 1950, then switched parties due to his liberal views, and was easily reelected as a Democrat in 1956 and 1962. The relatively unknown Packwood was given little chance, but after an 11th-hour debate with the incumbent before the City Club of Portland, which Packwood was generally considered to have won,[11] and a statewide recount in which over 100,000 ballots were challenged by both parties,[12] Packwood was declared the winner by 3,500 votes.[13] He then replaced Senator Ted Kennedy as the youngest senator.[14] Packwood was reelected in 1974, 1980, 1986, and 1992. He became "one of the country's most powerful elected officials".[15] His voting record was moderate. He supported restrictions on gun owners and liberal civil rights legislation.

Two years before Roe v. Wade he introduced the Senate's first abortion legalization bill, but he was unable to attract a cosponsor for either.[16] His pro-choice stance earned him the loyalty of many feminist groups[17] and numerous awards including those from the Planned Parenthood Federation of America (January 10, 1983) and the National Women's Political Caucus (October 23, 1985). In 1987, Packwood crossed party lines to vote against the nomination of Robert Bork to the Supreme Court, and he was one of only two Republicans to vote against the nomination of Clarence Thomas to the court.[3] Both votes were based on the nominee's opposition to abortion rights.[3]

Packwood differed with President Richard Nixon on some significant issues. He voted against Nixon's Supreme Court nominees Clement Haynsworth and G. Harrold Carswell, "two of Nixon's most embarrassing defeats,"[18] as well as Nixon's proposals for the B-1 bomber, submarines capable of carrying the Trident missile and the supersonic transport (SST).[18] He became the first Senate Republican to support Nixon's impeachment.[2] In a White House meeting of November 15, 1973, he told President Nixon that the public no longer believed the President and no longer trusted the integrity of the administration.[19]

He played a major role in the enactment of the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area Act,[20] which protected scenic Hells Canyon, the deepest river gorge in North America, by making it into a 652,488-acre (2,640.53 km2) National Recreation Area on the borders of northeastern Oregon and western Idaho.[21] Packwood sponsored the bill, and was credited with becoming "a genuine leader in the preservation battle" in Congress and in the end, second only to the idea's originator "the single most important individual in the history of Hells Canyon preservation".[22] Environmentalists also praised his advocacy of solar energy, returnable bottles and bike paths.[18]

Deregulation was another interest. In the late 1970s, he became a passionate supporter of trucking deregulation and a "persuasive spokesman" for reform. When deregulation became law, newspaper editorials praised Packwood for his pivotal role in the deregulation battle.[23]

He has been described as an ardent pro-Israel supporter. He, along with Tom Dine, opposed the F-15 sale to the Saudis under President Reagan.[24]

He was most noted for his role in the 1986 "unlikely triumph of tax reform" while he was chairman of the powerful Senate Finance Committee.[25] President Ronald Reagan had proposed the idea of tax reform in 1984, but Packwood's initial response was indifference. However, he played a leading role in fashioning a "radically new tax code that will raise business taxes by some $120 billion over five years—and lower personal income taxes by roughly the same amount."[3] Historians of the Act have written that his turnaround "revived the dying tax reform bill",[26] and credited his "ingenuity and astonishing legislative skill" for passage of the law,[27] which "despite its warts and wrinkles…succeeded at the fundamental purpose of reform".[28]

Packwood’s debating skills were rated A+ by USA Today in the issue of July 18, 1986.[citation needed] But his debating and legislative skills could kill bills as well as pass them. His "masterful" floor management has been credited with killing President Clinton's 1993 health care bill.[29] And he could be stubborn; in 1988 he was carried feet-first into the Senate Chamber by Capitol Police for a quorum call on campaign finance reform legislation.[30]

Packwood's political career began to unravel in November 1992, when a Washington Post story detailed claims of sexual abuse and assault from ten women, chiefly former staffers and lobbyists.[31] Publication of the story was delayed until after the 1992 election, as Packwood had denied the allegations and the Post had not gathered enough of the story at the time.[32][33] Packwood defeated Democrat Les AuCoin 52.1% to 46.5%. Eventually 19 women would come forward.[34]

As the situation developed, Packwood's diary became an issue. Wrangling over whether the diary could be subpoenaed and whether it was protected by the Fifth Amendment's protection against self-incrimination ensued. He did divulge 5,000 pages to the Senate Ethics Committee but balked when a further 3,200 pages were demanded by the committee. It was discovered that he had edited the diary, removing what were allegedly references to sexual encounters and the sexual abuse allegations made against him. Packwood then made what some of his colleagues interpreted as a threat to expose wrongdoing by other members of Congress. The diary allegedly detailed some of his abusive behavior toward women and, according to a press statement made by Richard Bryan, at that time serving as senator from Nevada, "raised questions about possible violations of one or more laws, including criminal laws".[35]

Despite public pressure for open hearings, the Senate ultimately decided against them. The Ethics committee's indictment, running to ten-volumes and 10,145 pages, much of it from Packwood's own writings, according to a report in The New York Times detailed, "the "sexual misconduct, obstruction of justice and ethics charges" being made against him.[36] The chairman of the Ethics committee, the Republican senator Mitch McConnell referred to Packwood's "habitual pattern of aggressive, blatantly sexual advances, mostly directed at members of his own staff or others whose livelihoods were connected in some way to his power and authority as a Senator" and said Packwood's behaviour included "deliberately altering and destroying relevant portions of his diary" which Packwood himself had written in the diary were "very incriminating information".[36]

With pressure mounting against him, Packwood announced his resignation from the Senate on September 7, 1995, in which he stated that he was "aware of the dishonor that has befallen me in the last three years" and "his duty to resign". following the Senate Ethics Committee unanimous recommendation that he be expelled from the Senate for ethical misconduct.[36] Democratic Congressman Ron Wyden won the seat in a special election.

After the sexual harassment case came to light, Packwood entered the Hazelden Foundation clinic for alcoholism in Minnesota, blaming his drinking for the harassments.[37]

Soon after leaving the Senate, Packwood founded the lobbying firm Sunrise Research Corporation. The former senator used his expertise in taxes and trade and his status as a former Senate Finance Committee chairman to land lucrative contracts with numerous clients, among them Northwest Airlines, Freightliner Corp. and Marriott International Inc.[38] Among other projects, he played a key role in the 2001 fight to repeal the estate tax.[citation needed]. In 2015, Packwood returned to the Senate as a witness for the Senate Finance Committee, which is again considering tax reform. He and Bill Bradley spoke on the 1986 Tax Reform bill.[39]

| U.S. Senate | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | U.S. senator (Class 3) from Oregon 1969–1995 Served alongside: Mark Hatfield |

Succeeded by |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by | Chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee 1981–1985 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee 1985–1987 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee January 4, 1995 – October 1, 1995 |

Succeeded by |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by | Chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee 1977–1979 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Chairman of the Senate Republican Conference 1979–1981 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee 1981–1983 |

Succeeded by |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by | Youngest Member of the United States Senate 1969–1971 |

Succeeded by |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Commerce and Manufactures (1816–1825) |

| |

| Commerce (1825–1947) |

| |

| Interstate Commerce (1887–1947) |

| |

| Interstate and Foreign Commerce/Commerce (1947–1977) |

| |

| Commerce, Science, and Transportation (1977–present) |

| |

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| People |

|

| Other |

|