|

No edit summary

|

→Observance in Christianity: Remove this section–no sources provided for its claims

|

||

| (45 intermediate revisions by 16 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Counting of the days from Passover to Shavuot}} |

{{Short description|Counting of the days from Passover to Shavuot}} |

||

{{Infobox holiday |

{{Infobox holiday |

||

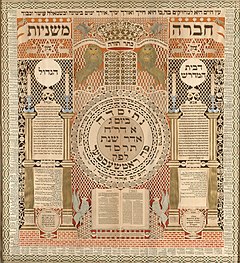

|image = Baruch Zvi Ring - Memorial Tablet and Omer Calendar - Google Art Project.jpg |

| image = Baruch Zvi Ring - Memorial Tablet and Omer Calendar - Google Art Project.jpg |

||

|caption = Omer Calendar |

| caption = Omer Calendar |

||

|holiday_name = Counting of the Omer |

| holiday_name = Counting of the Omer |

||

|official_name = |

| official_name = |

||

|observedby = '''[[Jews]]''' |

| observedby = '''[[Jews]]''' (In various forms also by: [[Samaritans]]; [[Messianic Jews]] and other [[Christian observance of Passover|Christians]], [[Groups claiming affiliation with Israelites|some groups claiming affiliation with Israelites]]) |

||

|longtype |

| longtype = Jewish and Samaritan, religious |

||

|begins = 16 Nisan |

| begins = 16 Nisan |

||

|ends = 5 Sivan |

| ends = 5 Sivan |

||

| date{{LASTYEAR}} |

| date{{LASTYEAR}} = {{Calendar date/infobox|year=last}} |

||

| date{{CURRENTYEAR}} = {{Calendar date/infobox|year=current}} |

| date{{CURRENTYEAR}} = {{Calendar date/infobox|year=current}} |

||

| date{{NEXTYEAR}} |

| date{{NEXTYEAR}} = {{Calendar date/infobox|year=next}} |

||

| date{{NEXTYEAR|2}} |

| date{{NEXTYEAR|2}} = {{Calendar date/infobox|year=next2}} |

||

|type = Jewish |

| type = Jewish |

||

|relatedto = [[Passover]], [[Shavuot]] |

| relatedto = [[Passover]], [[Shavuot]] |

||

|date= |

| date = |

||

}} |

|||

{{Sefirat HaOmer Box|floatright=floatright}} |

{{Sefirat HaOmer Box|floatright=floatright}} |

||

{{Judaism}} |

{{Judaism}} |

||

'''Counting of the Omer''' ({{Lang-he|סְפִירַת הָעוֹמֶר}}, '''Sefirat HaOmer''', sometimes abbreviated as '''Sefira |

'''Counting of the Omer''' ({{Lang-he|סְפִירַת הָעוֹמֶר}}, '''Sefirat HaOmer''', sometimes abbreviated as '''Sefira''') is a ritual in [[Judaism]]. It consists of a verbal counting of each of the 49 days between the holidays of [[Passover]] and [[Shavuot]]. The periodof49 days is known as the "omer period" or simplyas"the omer" or "sefirah".<ref name=":0">{{Cite web |title=Counting the Omer and Israel’s National Holidays - Jewish Tradition |url=https://yahadut.org/en/shabbat-and-festivals/counting-the-omer-and-israel-s-national-holidays/ |access-date=2024-04-01 |website=yahadut.org |language=en}}</ref> |

||

The count has its origins in the biblical command of the [[Omer offering]] (or sheaf-offering), which was offered on Passover, and after which 49 days were counted, and the Shavuot holiday was observed. Since the destruction of the [[Temple in Jerusalem]], the Temple sacrifices are no longer offered, but the counting until Shavuot is still performed. Shavuot is the only major Jewish holiday for which no calendar date is specified in the Torah; rather, its date is determined by the omer count.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

| ⚫ |

|

||

| ⚫ | The Counting of the ''Omer'' begins on the second day of Passover (the 16th of [[Nisan]]) for [[Rabbinic Judaism|Rabbinic Jews]] ([[Orthodox Judaism|Orthodox]], [[Conservative Judaism|Conservative]], [[Reform Judaism|Reform]]), and after the weekly ''[[Shabbat]]'' during Passover for [[Karaite Judaism|Karaite Jews]]. According to all practices, the 49-day count ends the day before Shavuot, which is the 'fiftieth day' of the count. |

||

The ''[[Omer (unit)|omer]]'' a ("[[Sheaf (agriculture)|sheaf]]") is an old [[Hebrew Bible|Biblical]] measure of volume of unthreshed stalks of [[Cereal|grain]]. The Sunday after the start of each farmer's [[barley]] grain harvest, a sheaf of barley from each farm was waved by a Priest in the [[Temple in Jerusalem]], signalling the allowance of the consumption of ''[[chadash]]'' (grains from the ''new'' harvest). Later tradition evolved to: during the [[Passover|Feast of Unleavened Bread]], an ''omer'' of [[barley]] was offered in the [[Temple in Jerusalem]], signalling the allowance of the consumption of ''[[chadash]]'' (grains from the ''new'' harvest). This offering happened on "the morrow after the day of rest", evolving to be re-interpreted either as the second day of [[Unleavened Bread]] on the 16th day of the month or as the day following the [[Shabbat]] during Passover. On the 50th day after the beginning of the count, corresponding to the holiday of Shavuot, two loaves made of wheat were offered in the Temple to signal the end of the wheat harvest or the re-interpreted beginning of the wheat harvest. |

|||

The ''[[Omer (unit)|omer]]'' ("[[Sheaf (agriculture)|sheaf]]") is an old [[Hebrew Bible|Biblical]] measure of volume of unthreshed stalks of [[Cereal|grain]], the amount of grain used for the Temple offering. |

|||

The origins of the "omer" count are from the Torah passages on the offerings for the start and end of the grain harvest, with the 50th day marking the official end with a large feast. The Torah itself, in {{bibleverse||Leviticus|23:15–16|HE}}, and {{bibleverse||Deuteronomy|16:9-12|HE}}, states that it is a commandment to count seven complete weeks from the start of the grain harvest ending with the festival of [[Shavuot]] on the fiftieth day. Shavuot has evolved to be known as the festival marking the giving of the Torah to the Hebrew nation on the 6th of the [[Hebrew calendar|Hebrew month]] of [[Sivan]]. |

|||

== Sources == |

== Sources == |

||

| Line 31: | Line 32: | ||

The commandment for counting the Omer is recorded within the Torah in {{bibleverse||Leviticus|23:9–21|HE}}: |

The commandment for counting the Omer is recorded within the Torah in {{bibleverse||Leviticus|23:9–21|HE}}: |

||

{{ |

{{blockquote|text=When ye are come into the land which I give unto you, and shall reap the harvest thereof, then ye shall bring the sheaf (''omer'') of the first-fruits of your harvest unto the priest. And he shall wave the sheaf before the LORD, to be accepted for you; on the morrow after the day of rest the priest shall wave it. ... And '''ye shall count unto you from the morrow after the day of rest, from the day that ye brought the sheaf of the waving; seven weeks shall there be complete; even unto the morrow after the seventh week shall ye number fifty days'''; and ye shall present a new meal-offering unto the LORD. ... And ye shall make proclamation on the selfsame day; there shall be a holy convocation unto you; ye shall do no manner of servile work; it is a statute for ever in all your dwellings throughout your generations.}} |

||

And in the day when ye wave the sheaf, ye shall offer a he-lamb without blemish of the first year for a burnt-offering unto the LORD. And the meal-offering thereof shall be two tenth parts of an ephah of fine flour mingled with oil, an offering made by fire unto the LORD for a sweet savour; and the drink-offering thereof shall be of wine, the fourth part of a hin. And ye shall eat neither bread, nor parched corn, nor fresh ears, until this selfsame day, until ye have brought the offering of your God; it is a statute for ever throughout your generations in all your dwellings. |

|||

And '''ye shall count unto you from the morrow after the day of rest, from the day that ye brought the sheaf of the waving; seven weeks shall there be complete; even unto the morrow after the seventh week shall ye number fifty days'''; and ye shall present a new meal-offering unto the LORD. Ye shall bring out of your dwellings two wave-loaves of two tenth parts of an ephah; they shall be of fine flour, they shall be baked with leaven, for first-fruits unto the LORD. And ye shall present with the bread seven lambs without blemish of the first year, and one young bullock, and two rams; they shall be a burnt-offering unto the LORD, with their meal-offering, and their drink-offerings, even an offering made by fire, of a sweet savour unto the LORD. And ye shall offer one he-goat for a sin-offering, and two he-lambs of the first year for a sacrifice of peace-offerings. And the priest shall wave them with the bread of the first-fruits for a wave-offering before the LORD, with the two lambs; they shall be holy to the LORD for the priest. And ye shall make proclamation on the selfsame day; there shall be a holy convocation unto you; ye shall do no manner of servile work; it is a statute for ever in all your dwellings throughout your generations.}} |

|||

As well as in {{bibleverse||Deuteronomy|16:9–12|HE}}: |

As well as in {{bibleverse||Deuteronomy|16:9–12|HE}}: |

||

{{ |

{{blockquote|text=Seven weeks shalt thou number unto thee; '''from the time the sickle is first put to the standing corn shalt thou begin to number seven weeks'''. And thou shalt keep the feast of weeks unto the LORD thy God...}} |

||

The obligation in post-Temple destruction times is a matter of dispute, as the Temple offerings which depend on the omer count are no longer offered. While [[Maimonides|Rambam (Maimonides)]] suggests that the omer count obligation is still biblical, most other commentaries assume that it is of a rabbinic origin in modern times.<ref>[https://www.sulamot.org/%D7%A1%D7%A4%D7%99%D7%A8%D7%AA-%D7%94%D7%A2%D7%95%D7%9E%D7%A8-%D7%91%D7%99%D7%9E%D7%99%D7%A0%D7%95-%D7%9E%D7%93%D7%90%D7%95%D7%A8%D7%99%D7%99%D7%AA%D7%90-%D7%90%D7%95-%D7%9E%D7%93%D7%A8%D7%91%D7%A0/ ספירת העומר בימינו – מדאורייתא או מדרבנן?]</ref> |

The obligation in post-Temple destruction times is a matter of dispute, as the Temple offerings which depend on the omer count are no longer offered. While [[Maimonides|Rambam (Maimonides)]] suggests that the omer count obligation is still biblical, most other commentaries assume that it is of a rabbinic origin in modern times.<ref>[https://www.sulamot.org/%D7%A1%D7%A4%D7%99%D7%A8%D7%AA-%D7%94%D7%A2%D7%95%D7%9E%D7%A8-%D7%91%D7%99%D7%9E%D7%99%D7%A0%D7%95-%D7%9E%D7%93%D7%90%D7%95%D7%A8%D7%99%D7%99%D7%AA%D7%90-%D7%90%D7%95-%D7%9E%D7%93%D7%A8%D7%91%D7%A0/ ספירת העומר בימינו – מדאורייתא או מדרבנן?]</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ |

[[File:Wheat sheaves near King's Somborne - geograph.org.uk - 889992.jpg|thumb|Modern |

||

The idea of counting each day represents spiritual preparation and anticipation for the giving of the Torah,<ref>{{cite book|last=Scherman|first=Nosson (translation and anthology)|title=The Complete ArtScroll Siddur (Nusach Ashkenaz)|year=1984|edition=First Impression|publisher=Mesorah Publications, Ltd|location=Brooklyn, NY, USA|isbn=0-89906-650-X|page=283}}</ref> which God gave on [[Biblical Mount Sinai|Mount Sinai]] at the beginning of the [[Hebrew calendar|month]] of [[Sivan]], around the same time as the holiday of Shavuot. The [[Sefer HaChinuch]] (published anonymously in 13th-century Spain) states that the Israelites were only freed from [[Ancient Egypt|Egypt]] at Passover in order to receive the Torah at Sinai, an event which is now celebrated on Shavuot, and to fulfill its laws. The Counting of the ''Omer'' demonstrates how much a Jew desires to accept the Torah in their own life. |

|||

| ⚫ |

|

||

In keeping with the themes of spiritual growth and character development during this period, [[Rabbinic literature]]<ref name=aish>{{cite web|last=Weisz|first=Noson|title=Mind Over Matter|date=20 February 2006|url=http://www.aish.com/h/o/t/48969151.html|publisher=Aish HaTorah, Israel|access-date=7 April 2013|archive-date=17 March 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130317030834/http://www.aish.com/h/o/t/48969151.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> compares the process of growth to the two types of grain offered at either pole of the counting period. In ancient times, barley was simpler food while wheat was a more luxurious food. At Passover, the children of Israel were raised out of the Egyptian exile although they had sunken almost to the point of no return. [[The Exodus]] was an unearned gift from God, like the food of simple creatures that are not expected to develop their spiritual potential. The receiving of the Torah created spiritual elevation and active cooperation. Thus the Shavuot offering is "people food".<ref name=aish /> |

|||

== The count == |

== The count == |

||

[[File:The National Library of Israel - Counting of the Omer, Morocco, Tangier.ogg|right|thumb|Counting the Omer in [[Tangier]], [[Morocco]], in the 1960s]] |

[[File:The National Library of Israel - Counting of the Omer, Morocco, Tangier.ogg|right|thumb|Counting the Omer in [[Tangier]], [[Morocco]], in the 1960s]] |

||

[[File:The National Library of Israel - Counting of the Omer, Poland, Galicia.ogg|right|thumb|Counting the Omer, Polish version, recorded in [[Jerusalem]] in 1952 |

[[File:The National Library of Israel - Counting of the Omer, Poland, Galicia.ogg|right|thumb|Counting the Omer, Polish version, recorded in [[Jerusalem]] in 1952]] |

||

{{Sefirat HaOmer Box|floatright=floatright}} |

{{Sefirat HaOmer Box|floatright=floatright}} |

||

As soon as it is definitely night (approximately thirty minutes after sundown), the one who is counting the ''Omer'' recites this blessing: |

As soon as it is definitely night (approximately thirty minutes after sundown), the one who is counting the ''Omer'' recites this blessing: |

||

{{ |

{{blockquote|text={{transliteration|he|Barukh atah, A-donai E-loheinu, Melekh Ha-ʿolam, asher qid'shanu b'mitzvotav v'tzivanu ʿal S'firat Ha-ʿomer.}}<br/> |

||

Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the Universe, Who has sanctified us with His commandments and commanded us to count the Omer.|sign=|source=}} |

Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the Universe, Who has sanctified us with His commandments and commanded us to count the Omer.|sign=|source=}} |

||

Then he or she states the ''Omer''-count in terms of both total days and weeks and days. For example: |

|||

| ⚫ |

|

||

* On the first day: "Today is one day of the omer" |

|||

* On the eighth day: "Today is eight days, which is one week and one day of the omer" |

|||

| ⚫ | The wording of the count differs slightly between customs: the last Hebrew word is either ''laomer'' (literally "to the omer") or ''baomer'' (literally "in the omer"). Both customs are valid according to [[halakha]].<ref>{{cite web|last=Bulman|first=Nachman|title=Ask The rabbi|url=http://ohr.edu/ask_db/ask_main.php/63/Q2/|work=Shulchan Oruch, Orach Chaim 489:1, 493:2; Mishneh Brurah 489:8|publisher=Ohr Somayach, Israel|access-date=7 April 2013}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ |

|

||

| ⚫ | The count is generally in [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]]; it may also be counted in any language, however one must understand what one is saying.<ref>{{cite web|last=Torah.org|title=Sefiras Ha'Omer|url=http://www.torah.org/learning/yomtov/omer/sefira.php3|publisher=Project Genesis, USA|access-date=7 April 2013|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130330073814/http://www.torah.org/learning/yomtov/omer/sefira.php3|archive-date=30 March 2013}}</ref> |

||

The counting is preferably done at night, at the beginning of the Jewish day. If one realizes the next morning or afternoon that they have not yet counted, the count may still be made, but without a blessing. If one forgets to count a day altogether, he or she may continue to count succeeding days, but without a blessing.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Mitzva to Count the Omer - Jewish Tradition |url=https://yahadut.org/en/shabbat-and-festivals/counting-the-omer-and-israel-s-national-holidays/the-mitzva-to-count-the-omer/ |access-date=2024-04-01 |website=yahadut.org |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | [[File:Wheat sheaves near King's Somborne - geograph.org.uk - 889992.jpg|thumb|Modern-day wheat sheaves]] |

||

| ⚫ | In the rabbinic chronology, the giving of the Torah at [[Mount Sinai]] happened on Shavuot. Thus, the omer period is one of preparation and anticipation for the giving of the Torah.<ref>{{cite book|last=Scherman|first=Nosson (translation and anthology)|title=The Complete ArtScroll Siddur (Nusach Ashkenaz)|year=1984|edition=First Impression|publisher=Mesorah Publications, Ltd|location=Brooklyn, NY, USA|isbn=0-89906-650-X|page=283}}</ref> According to ''[[Aruch HaShulchan]]'', already in Egypt [[Moses]] announced to the Israelites that they would celebrate a religious ceremony at [[Mount Sinai]] once 50 days had passed, and the people was so excited by this that they counted the days until that ceremony took place. Homiletically, in modern times when the Temple sacrifices of Shavuot are not offered, counting the omer still has a purpose as a remembrance of the counting up to Sinai.<ref>[[Aruch Hashulchan]] Orach Chaim 489:2; quoting [[Nissim of Gerona|Ran]], end of [[Pesachim]]; the midrash in question appears not to be preserved in any extant midrash collection. Text in Aruch Hashulchan:ובהגדה אמרו בשעה שאמר להם משה תעבדון את אלקים על ההר הזה אמרו לו ישראל משה רבינו אימתי עבודה זו אמר להם לסוף נ' יום והיו מונין כל אחד ואחד לעצמו מכאן קבעו חכמים לספירת העומר כלומר בזמן הזה שאין אנו מביאין קרבן ולא עומר אלא מחשבין נ' יום לשמחת התורה כמו שמנו ישראל באותו זמן וזהו דרך דרש</ref> |

||

One explanation for the Counting of the Omer is that it shows the connection between Passover and Shavuot. The physical freedom that the Hebrews achieved at the Exodus from Egypt was only the beginning of a process that climaxed with the spiritual freedom they gained at the giving of the Torah on Shavuot. The [[Sefer HaChinuch]] states that the Israelites were only freed from [[Ancient Egypt|Egypt]] at Passover in order to receive the Torah.<ref>[[Sefer HaChinuch]], 306</ref> The Counting of the ''Omer'' demonstrates how much a Jew desires to accept the Torah in their own life. |

|||

According to [[Maharal]], there is a symbolic contrast between the [[omer offering]] (offered on Passover) and the Shavuot sacrifice (''shtei halechem'') offered upon conclusion of the omer. The former consists of barley, which is typically an animal food, and represents the low and passive spiritual level of the Israelites immediately upon leaving Egypt; while the latter consists of wheat and represents the high and active spiritual level of the Israelites upon receiving the Torah.<ref>[https://www.toraland.org.il/%D7%9E%D7%90%D7%9E%D7%A8%D7%99%D7%9D/%D7%91%D7%9E%D7%A2%D7%92%D7%9C-%D7%94%D7%A9%D7%A0%D7%94/%D7%9C%D7%92-%D7%91%D7%A2%D7%95%D7%9E%D7%A8/%D7%9C%D7%94%D7%A0%D7%99%D7%A3-%D7%90%D7%AA-%D7%94%D7%A2%D7%95%D7%9E%D7%A8/ להניף את העומר]</ref> |

|||

In Israel, the omer period coincides with the final ripening period of wheat before it is harvested around Shavuot. In this period, the quality of the harvest is very sensitive, and can easily be ruined by bad weather.<ref>cf. {{Bibleverse|1 Samuel|12:17-19|HE}}</ref> Thus, the omer period stresses human vulnerability and dependence on God.<ref>{{Alhatorah|Vayikra|23:17|Sforno}}</ref> |

|||

According to [[Nahmanides]], Passover and Shavuot effectively form one extended holiday, with the seven weeks of the omer paralleling the seven days of Passover or [[Sukkot]], and the omer period paralleling [[Chol Hamoed]].<ref>{{Alhatorah|Vayikra|23:37|Ramban}}</ref> |

|||

==Karaite and Samaritan practice== |

==Karaite and Samaritan practice== |

||

[[Karaite Judaism|Karaite Jews]] and [[Samaritans|Israelite Samaritans]] begin counting the ''Omer'' on the day after the weekly Sabbath during |

[[Karaite Judaism|Karaite Jews]] and [[Samaritans|Israelite Samaritans]] begin counting the ''Omer'' on the day after the weekly Sabbath during [[Passover]], rather than on the second day of Passover (the 16th of Nisan). |

||

|

This is due to differing interpretations of {{Bibleverse|Leviticus|23:15–16|HE}}, where the Torah says to begin counting from the "morrow after the day of rest".<ref>{{cite web|title=Karaites Counting the Omer|date=4 April 2013|url=http://abluethread.com/2013/04/04/but-whos-counting-anyway/#more-1148}}</ref> Rabbinic Jews interpret the "day of rest" to be the first day of Passover, while Karaites and Samaritans understand it to be the first weekly Sabbath that falls during Passover. Thus, the Karaite and Samaritan Shavuot is always on a Sunday, although the actual Hebrew date varies (which complements the fact that a specific date is never given for Shavuot in the Torah, the only holiday for which this is the case).<ref>{{cite web|title=Count for the Omer|date=10 April 2020|url=http://www.karaite-korner.org/omer.shtml}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=What is shavuot?|url=http://www.karaite-korner.org/shavuot.shtml}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Samaritan Shavuot|date=3 June 2014 |url=http://www.israelite-samaritans.com/religion/shavuot/}}</ref> Historically, Karaite and Karaite-adjacent religious leaders such as [[Anan ben David]], [[Benjamin Nahawandi]], [[Muhammad ibn Isma'il]], [[Al-Tiflisi|Musa of Tiflis]] (founder of a 9th-century Jewish movement in Babylon); and Malik al Ramli (founder of a 9th-century Jewish movement in the LandofIsrael) concluded that Shavuot should fall outona Sunday.<ref name="Ankori p276">{{cite book |last=Ankori |first=Zvi |title=Karaites in Byzantium |page=276}}</ref> This is also the opinion of [[Catholics]]<ref name="jewishencyclopedia.com">{{cite web | last1 = Kohler | first1 = Kaufmann | first2 = J. L. | last2 = Magnus | url = http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=177&letter=P | title = Pentecost | publisher = [[Jewish Encyclopedia]] | access-date = May 29, 2009 | year = 2002 }}</ref> and the historical [[Sadducees]] and [[Boethusians]]. |

||

The counting of Karaite and Rabbinic Jews coincides when the first day of Passover is on the Sabbath. Samaritan Judaism has an additional difference: because the date of the Samaritan Passover usually differs from the Jewish one by approximately one lunar month,<ref>{{cite web|title=The Samaritan calendar|date=14 May 2020 |url=http://www.israelite-samaritans.com/religion/calendar/}}</ref> the Karaite and Samaritan counting rarely coincides, despite each beginning on a Sunday. |

|||

Other non-Rabbinical religious leaders such as [[Anan ben David]] (founder of the Ananites); Benjamin al-Nahawandi (founder of the Benjaminites); Ismail al-Ukbari (founder of a 9th-century messianic Jewish movement in Babylon); Musa of Tiflis (founder of a 9th-century Jewish movement in Babylon); and Malik al Ramli (founder of a 9th-century Jewish movement in the Land of Israel) additionally recognized that Shavuot should fall out on a Sunday.<ref name="Ankori p276">{{cite book |last=Ankori |first=Zvi |title=Karaites in Byzantium |page=276}}</ref> |

|||

[[Ethiopian Jews]] traditionally had yet another practice: they interpreted the "day of rest" to be the ''last'' day of Passover, rather than being the first day (as in rabbinic tradition) or else the Sabbath (as for Karaites). |

|||

[[Catholic Church|Catholics]]<ref name="jewishencyclopedia.com">{{cite web | last1 = Kohler | first1 = Kaufmann | first2 = J. L. | last2 = Magnus | url = http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=177&letter=P | title = Pentecost | publisher = [[Jewish Encyclopedia]] | access-date = May 29, 2009 | year = 2002 }}</ref> and the historical [[Sadducees]] and [[Boethusians]], dispute the Rabbinic interpretation. They infer the "Shabbat" referenced is the weekly Shabbat. Accordingly, the counting of the Omer always begins on the Sunday of Passover, and continues for 49 days, so that Shavuot would always fall on a Sunday as well. |

|||

==Omer-counters== |

==Omer-counters== |

||

[[File:Luach.jpg|thumb|1826 Omer calendar-book from [[Verona]] (Italy), in the collection of the [[Jewish Museum of Switzerland]] |

[[File:Luach.jpg|thumb|1826 Omer calendar-book from [[Verona]] (Italy), in the collection of the [[Jewish Museum of Switzerland]]]] |

||

"''Omer''-counters" ({{Script/Hebrew|לוּחַ סְפִירָת הָעוֹמֶר}}) are devices which aid in remembering the |

"''Omer''-counters" ({{Script/Hebrew|לוּחַ סְפִירָת הָעוֹמֶר}}) are devices which aid in remembering the correct day of the omer count. They are often on display in [[synagogue]]s for the benefit of worshippers who count the ''Omer'' with the congregation at the conclusion of evening services. ''Omer''-counters come in varying forms such as: |

||

* decorative boxes with an interior scroll that shows each day's count through a small opening |

* decorative boxes with an interior scroll that shows each day's count through a small opening |

||

* posters and magnets in which each day's count is recorded on a tear-off piece of paper |

* posters and magnets in which each day's count is recorded on a tear-off piece of paper |

||

* calendars depicting all seven weeks and 49 days of the ''Omer'', on which a small pointer is advanced from day to day |

* calendars depicting all seven weeks and 49 days of the ''Omer'', on which a small pointer is advanced from day to day |

||

* pegboards that keep track of both the day and the week of the ''Omer''. |

* pegboards that keep track of both the day and the week of the ''Omer''. |

||

Reminders to count the ''Omer'' are also produced for tablet computers and via [[ |

Reminders to count the ''Omer'' are also produced for tablet computers and via [[SMS]] for [[mobile phone]]s. |

||

An omer counter from the 19th century in [[Lancaster, Pennsylvania]] is preserved at the [[Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies]].<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Professionalization of Wisdom: The Legacy of Dropsie College and Its Library, in Michael Ryan and Dennis Hyde, eds., The Penn Libraries Collections at 250|last=Kiron|first=Arthur|publisher=University of Pennsylvania Library|year=2000|location=Philadelphia|pages=182}}</ref> |

|||

== As a period of semi-mourning == |

== As a period of semi-mourning == |

||

The omer period has developed into a time of semi-mourning in Jewish custom. |

|||

{{Teshuva}} |

|||

The period of counting the Omer is also a time of semi-mourning. During this time, traditional Jewish custom forbids haircuts, shaving, listening to instrumental music, or conducting weddings, parties, and dinners with dancing.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Karo |first1=Joseph |title=Shulkhan Aruch |url=https://www.sefaria.org/Shulchan_Arukh%2C_Orach_Chayim.493 |publisher=Sefaria}}</ref> Traditionally, the reason cited is that this is in memory of a plague that killed the 24,000 students of [[Rabbi Akiva]] (ca. 40–ca. 137 CE). According to the [[Talmud]], {{cn|date=April 2022}} 12,000 ''[[chavruta]]'' (pairs of Torah study partners), 24,000 in all, were killed (they were either killed by the Romans during the [[Bar Kokhba revolt]] 132–136 CE or they died in a "plague") as a sign of Divine anger during the days of the ''Omer''-counting for not honoring one another properly as befits [[Talmid Chacham|Torah scholars]]. |

|||

Traditionally, the mourning is in memory of the death of [[Rabbi Akiva]]'s 24,000 students, as described in the [[Talmud]].<ref>Yebamot 62b</ref> (According to the Talmud they died in a "plague" as punishment for not honoring one another properly, but the Sephardic manuscript of [[Iggeret of Rabbi Sherira Gaon]] describes them as dying due to "persecution" (''shmad''), and based on this some modern scholars have suggested that they died in the [[Bar Kokhba revolt]].<ref>[[Solomon Judah Loeb Rapoport]], Kerem Hemed [https://books.google.com/books?id=kOg6AQAAMAAJ&dq=editions:dBX-PxBgmScC&pg=PP7 7:183]; [[Shmuel Safrai]], ''Rabbi Akiva ben Yosef: Hayav Umishnato'' (1970), p.27; R' [[Meir Mazuz]], [https://www.ykr.org.il/media/old_storage/4213.pdf Bayit Neeman 60 p.3]{{Dead link|date=December 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref>) Rabbi [[Yechiel Michel Epstein]] (author of ''[[Aruch HaShulchan]]'') postulates that the mourning period also memorializes Jews who were murdered during the [[Crusades]], [[pogrom]]s, and [[blood libel]]s that occurred in [[Europe]].<ref>{{cite web|last=Kahn|first=Ari|title=Rebbe Akiva's 24,000 Students|date=20 February 2006|url=http://www.aish.com/h/o/33o/48970241.html|publisher=Aish HaTorah, Israel|access-date=8 April 2013}}</ref> The observance of mourning customs was strengthened after the [[Rhineland massacres]] and [[Cossack riots]] which occurred in the Omer period.<ref>[[Daniel Sperber]], Minhagei Yisrael 1:107-8</ref> In modern times, [[the Holocaust]] is generally included among those events which are memorialized, in particular [[Yom HaShoah]] is observed during the ''Omer''.<ref>{{cite web | last=Rosenberg | first=Jennifer | title=How Is Holocaust Remembrance Day Observed by the Jewish Community? | website=ThoughtCo | date=2010-01-01 | url=https://www.thoughtco.com/yom-hashoah-1778162}}</ref> |

|||

[[Lag BaOmer]], the thirty-third day of the Counting of the Omer, is considered to be the day in which the plague was lifted, (and/or the day in which the rebellion saw a victory during the [[Bar Kokhba revolt|uprising of Bar Kochba]]) so on that day, all the rules of mourning are lifted. |

|||

| ⚫ | Mourning practices are observed for only part of the Omer period, with different communities observing different parts. Some families listen to music during the week of [[Passover]] and then commence the period of mourning until Lag BaOmer. Some [[Sephardi Jews|Sephardic]] Jewish families begin the period of mourning from the first day of the Hebrew month of [[Iyar]] and continue for 33 days until the third of [[Sivan]]. The custom among Jerusalemites (''minhag Yerushalmi'') is to follow the mourning practices during the entire Counting of the Omer, save for the day of [[Lag BaOmer]] and the last three days of the counting (''sheloshet yemei hagbalah'') prior to the onset of [[Shavuot]]. Many [[Religious Zionism|Religious Zionists]] suspend some or all of the mourning customs on [[Yom Ha'atzmaut]] (Israel's Independence Day). The extent of mourning is also based heavily on family custom, and therefore Jews will mourn to different degrees. |

||

| ⚫ |

|

||

Lag BaOmer, the thirty-third day of the Omer, is considered to be the day on which the students stopped dying, so all the rules of mourning are lifted. Some [[Sephardi Jews]], however, continue the mourning period up until the 34th day of the ''Omer'', which is considered by them to be the day of joy and celebration. [[Spanish and Portuguese Jews]] do not observe these customs. |

|||

| ⚫ |

|

||

| ⚫ | During the days of mourning, custom generally forbids haircuts, shaving, listening to instrumental music, or conducting weddings, parties, and dinners with dancing.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Karo |first1=Joseph |title=Shulkhan Aruch |url=https://www.sefaria.org/Shulchan_Arukh%2C_Orach_Chayim.493 |publisher=Sefaria}}</ref> Some religious Jews shave each Friday afternoon during the mourning period of the ''Omer'' in order to be neat in honor of the Shabbat, and some men do so in order to appear neat in their places of employment. |

||

Rabbi [[Yechiel Michel Epstein]] (1829–1908), author of ''[[Aruch HaShulchan]]'', postulates that the mourning period also memorializes Jews who were murdered during the [[Crusades]] (the 11th-, 12th- and 13th-century religious military campaigns), [[pogrom]]s (19th- and 20th-century [[Anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire|attacks on Jews in the Russian Empire]]) and [[blood libel]]s that occurred in [[Europe]].<ref>{{cite web|last=Kahn|first=Ari|title=Rebbe Akiva's 24,000 Students|date=20 February 2006|url=http://www.aish.com/h/o/33o/48970241.html|publisher=Aish HaTorah, Israel|access-date=8 April 2013}}</ref> In modern times, the [[Holocaust]] is generally included among those events which are memorialized, in particular [[Yom Hashoah]] is observed during the ''Omer''.<ref>{{cite web | last=Rosenberg | first=Jennifer | title=How Is Holocaust Remembrance Day Observed by the Jewish Community? | website=ThoughtCo | date=2010-01-01 | url=https://www.thoughtco.com/yom-hashoah-1778162}}</ref> |

|||

The Jewish calendar is largely agricultural, and the period of ''Omer'' falls between [[Passover]] and [[Shavuot]]. On Passover there is a shift from praying for rain to praying for dew and this coincides with the growth period for the fruit of the season. Shavuot is the day of the giving of the first fruits (''bikkurim''). The outcome of the season's crop and fruit was still vulnerable during this period. Over these seven weeks, daily reflection, work on improving one's personality characteristics (''middot'') and potential inner growth from this work on one self was one way to pray for and invite the possibility of affecting one's external fate and potential – the growth of the crop and the fruit of that season. |

|||

Although the period of the Omer is traditionally a mourning one, on Lag BaOmer Jews can do actions that are not allowed during mourning. Many [[Religious Zionism|Religious Zionists]] trim their beards or shave their growth, and do other actions that are typically not allowed during the mourning period, on [[Yom Ha'atzmaut]] (Israel's Independence Day). |

|||

== Lag BaOmer == |

== Lag BaOmer == |

||

| Line 106: | Line 110: | ||

According to some [[Rishonim]], it is the day on which the plague that killed [[Rabbi Akiva]]'s 24,000 disciples came to an end, and for this reason the mourning period of [[Sefirat HaOmer]] concludes on Lag BaOmer in many communities.{{sfnp|Walter|2018|p=192}} |

According to some [[Rishonim]], it is the day on which the plague that killed [[Rabbi Akiva]]'s 24,000 disciples came to an end, and for this reason the mourning period of [[Sefirat HaOmer]] concludes on Lag BaOmer in many communities.{{sfnp|Walter|2018|p=192}} |

||

According to modern [[ |

According to modern [[kabbalistic]] tradition, this day is the [[Hillula of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai|Celebration]] of [[Simeon ben Yohai|Simeon ben Yochai]] and/or the anniversary of his death. According to a [[late-medieval]] tradition, Simeon ben Yochai is buried in Meron, and this association has spawned several well-known customs and practices on Lag BaOmer, including the lighting of [[bonfire]]s and pilgrimages to [[Meron, Israel|Meron]].<ref name="Brodt">{{cite web |last=Brodt |first=Eliezer |title=A Printing Mistake and the Mysterious Origins of Rashbi's Yahrzeit |url=https://seforimblog.com/2011/05/printing-mistake-and-mysterious-origins/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200513133221/https://seforimblog.com/2011/05/printing-mistake-and-mysterious-origins/ |archive-date=13 May 2020 |access-date=7 May 2015 |website=seforimblog.com |date=19 May 2011 }}</ref>[[File:Rashbi.jpg|thumb|right|225px|Mark (behind blue fence) over cave in which Rabbi Ele'azar bar Shim'on is buried. This main hall is [[Mechitza|divided in half]] in order to separate between men and women.]] |

||

== Kabbalistic interpretation == |

== Kabbalistic interpretation == |

||

The period of the counting of the ''Omer'' is considered to be a time of potential for inner |

The period of the counting of the ''Omer'' is considered to be a time of potential for inner growth—for a person to work on one's good characteristics (''middot'') through reflection and development of one aspect each day for the 49 days of the counting. |

||

| ⚫ | In [[Kabbalah]], each of the seven weeks of the ''Omer''-counting is associated with one of the seven lower [[sephirot|sefirot]] ([[Chesed#Kabbalah|Chesed]], [[Gevurah]], [[Tiferet]], [[Netzach]], [[Hod (Kabbalah)|Hod]], [[Yesod]], [[Malkuth]]). Similarly, each day of each week is associated with one of these same seven ''sefirot'', creating forty-nine permutations. The first day of the ''Omer'' is therefore associated with "''chesed'' that is in ''chesed''" (loving kindness within loving kindness), the second day with "''gevurah'' that is in ''chesed''" (might within loving kindness); the first day of the second week is associated with "''chesed'' that is in ''gevurah''" (loving-kindness within might), the second day of the second week with "''gevurah'' that is in ''gevurah''" (might within might), and so on. |

||

In [[Kabbalah]], each of the seven weeks of the ''Omer''-counting is associated with one of the seven lower [[sephirot|sefirot]]: |

|||

| ⚫ | Symbolically, each of these 49 permutations represents an aspect of each person's character that can be improved or further developed. Recent books which present these 49 permutations as a daily guide to personal character growth have been published by Rabbi [[Simon Jacobson]]<ref>{{cite web|last=Jacobson|first=Simon|title=Your Guide to Personal Freedom Counting the Omer: Week One|url=http://www.meaningfullife.com/torah/holidays/8b/Your_Guide_to_Personal_Freedom_-_Week_1.php|work=Excerpt from "A Spiritual Guide to Counting the Omer"|publisher=meaningfullife.com|access-date=8 April 2013|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130310054235/http://www.meaningfullife.com/torah/holidays/8b/Your_Guide_to_Personal_Freedom_-_Week_1.php|archive-date=10 March 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Jacobson|first=Simon|title=Spiritual Guide to the Counting of the Omer|year=1996|publisher=Meaningful Life Center|isbn=978-1886587236|pages=72}}</ref> and Rabbi [[Yaacov Haber]] and David Sedley.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Haber |first1=Yaacov |title=Sefiros: Spiritual Refinement Through Counting the Omer |last2=David |first2=Sedley |publisher=TorahLab |year=2008 |isbn=978-1-60763-010-4 |pages=160}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | last=Adlerstein | first=Yitzchok | title=Sefirah, Sefiros, and Getting G-d Wrong | website=Cross-Currents | date=2008-04-24 | url=https://cross-currents.com/2008/04/24/sefirah-sefiros-and-getting-g-d-wrong/ | access-date=2024-05-24}}</ref> The work ''Counting the Omer: A Kabbalistic Meditation Guide''<ref>{{cite book|last=Kantrowitz|first=Min|title=Counting the Omer: A Kabbalistic Meditation Guide|year=2009|publisher=Gaon Books|isbn=978-1-935604-00-6 |pages=244|url=http://www.rabbiminkantrowitz.com/}}</ref> includes meditations, activities and ''[[Kavanah|kavvanot]]'' (proper mindset) for each of the kabbalistic four worlds for each of the 49 days. |

||

#[[Chesed#Kabbalah|Chesed]] (loving-kindness) |

|||

#[[Gevurah]] (might) |

|||

#[[Tiferet|Tipheret]] (beauty) |

|||

#[[Netzach]] (victory) |

|||

#[[Hod (Kabbalah)|Hod]] (acknowledgment) |

|||

#[[Yesod]] (foundation) |

|||

#[[Malkuth|Malchut]] (kingdom) |

|||

| ⚫ | The 49-day period of counting the Omer is also a conducive time to study the teaching of the [[Mishnah]] in [[Pirkei Avot]] 6:6, which enumerates the "48 ways" by which Torah is acquired. Rabbi [[Aharon Kotler]] (1891–1962) explains that the study of each "way" can be done on each of the first forty-eight days of the ''Omer''-counting; on the forty-ninth day, one should review all the "ways."<ref>{{cite web|last=Weinberg|first=Noah|title=Counting with the 48 Ways|date=7 May 2003|url=http://www.aish.com/h/o/t/52829142.html|publisher=Aish HaTorah, Israel|access-date=8 April 2013}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ |

|

||

| ⚫ |

Symbolically, each of these 49 permutations represents an aspect of each person's character that can be improved or further developed. |

||

| ⚫ |

The |

||

==Observance in Christianity== |

|||

Most Christian sects do not observe The Omer. The Christian holiday of [[Pentecost]] is named after Shavuot with similar timing but it otherwise unrelated. |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

* [[Bible code]], a purported set of secret messages encoded within the Torah. |

|||

* [[Biblical and Talmudic units of measurement]] |

|||

* [[Chol HaMoed]], the intermediate days during Passover and Sukkot. |

|||

* [[Chronology of the Bible]] |

|||

* [[Gematria]], Jewish system of assigning numerical value to a word or phrase. |

|||

* [[Hebrew calendar]] |

* [[Hebrew calendar]] |

||

* [[Hebrew numerals]] |

|||

* [[Jewish and Israeli holidays 2000–2050]] |

|||

* [[Lag BaOmer]], 33rd day of counting the ''Omer''. |

|||

* [[Notarikon]], a method of deriving a word by using each of its initial letters. |

|||

* [[Sephirot]], the 10 attributes/emanations found in Kabbalah. |

|||

* [[Significance of numbers in Judaism]] |

|||

* [[Weekly Torah portion]], division of the Torah into 54 portions. |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist}} |

||

| Line 151: | Line 131: | ||

{{refbegin}} |

{{refbegin}} |

||

* {{Cite book |last=Ariel |first=Yaakov S. |title=Evangelizing the chosen people: missions to the Jews in America, 1880–2000 |year=2000 |publisher=University of North Carolina Press |location=Chapel Hill |isbn=978-0-8078-4880-7 |oclc=43708450 }} |

* {{Cite book |last=Ariel |first=Yaakov S. |title=Evangelizing the chosen people: missions to the Jews in America, 1880–2000 |year=2000 |publisher=University of North Carolina Press |location=Chapel Hill |isbn=978-0-8078-4880-7 |oclc=43708450 }} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Cohn-Sherbok |first=Dan | |

* {{cite book |last=Cohn-Sherbok |first=Dan |authorlink=Dan Cohn-Sherbok |title=Messianic Judaism: A Critical Anthology |year=2000 |publisher=Continuum International Publishing Group |location=London; New York |isbn=978-0-8264-5458-4 |lccn=99050300 }} |

||

* {{cite book |last=Walter |first=Moshe |title=The Making of a Minhag: The Laws and Parameters of Jewish Customs |year=2018 |publisher=Feldheim Publishers |location=Jerusalem |isbn=9781680253368 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oAVgtgEACAAJ |language=en }} |

* {{cite book |last=Walter |first=Moshe |title=The Making of a Minhag: The Laws and Parameters of Jewish Customs |year=2018 |publisher=Feldheim Publishers |location=Jerusalem |isbn=9781680253368 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oAVgtgEACAAJ |language=en }} |

||

{{refend}} |

{{refend}} |

||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{ |

{{commons category|Counting of the Omer}} |

||

* [http://www.thejc.com/judaism/jewish-words/48270/sefirat-haomer Sefirat ha'omer/Counting the Omer, by Rabbi Julian Sinclair, April 28, 2011; Jewish Chronicle Online] |

* [http://www.thejc.com/judaism/jewish-words/48270/sefirat-haomer Sefirat ha'omer/Counting the Omer, by Rabbi Julian Sinclair, April 28, 2011; Jewish Chronicle Online] |

||

* [http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/judaica/ejud_0002_0015_0_15098.html Encyclopedia Judaica on Jewish Virtual Library] |

* [http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/judaica/ejud_0002_0015_0_15098.html Encyclopedia Judaica on Jewish Virtual Library] |

||

* [http://mishkan.org/omer?title=Omer Spiritual practices and reflections for each day from Mishkan Tefilah] |

* [http://mishkan.org/omer?title=Omer Spiritual practices and reflections for each day from Mishkan Tefilah] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141103021805/http://mishkan.org/omer?title=Omer |date=2014-11-03 }} |

||

* [http://chabad.org/holidays/sefirah/omer-count.htm The traditional liturgy from Chabad] |

* [http://chabad.org/holidays/sefirah/omer-count.htm The traditional liturgy from Chabad] |

||

* Rabbi [[Eliezer Melamed]] – [[Peninei Halakha]] – [http://ph.yhb.org.il/en/category/zemanim/05-02/ Counting the Omer] |

* Rabbi [[Eliezer Melamed]] – [[Peninei Halakha]] – [http://ph.yhb.org.il/en/category/zemanim/05-02/ Counting the Omer] |

||

* Rabbi [[Yitzchak Ginsburgh]] - [http://counting-the-omer.wixsite.com/50-days-eng/ Short video teachings for each day of the Omer] |

|||

=== manuscripts about the counting of the Omer === |

=== manuscripts about the counting of the Omer === |

||

* [https://www.nli.org.il/en/discover/manuscripts/hebrew-manuscripts/itempage?docId=PNX_MANUSCRIPTS990000596850205171&vid=MANUSCRIPTS |

* [https://www.nli.org.il/en/discover/manuscripts/hebrew-manuscripts/itempage?docId=PNX_MANUSCRIPTS990000596850205171&vid=MANUSCRIPTS Secret of the Counting of the Omer], [[Moses of Burgos]], 13th - 14th centuries, Ktiv project, [[National Library of Israel]] |

||

* [https://www.nli.org.il/he/discover/manuscripts/hebrew-manuscripts/itempage?docId=PNX_MANUSCRIPTS990031594990205171&vid=MANUSCRIPTS |

* [https://www.nli.org.il/he/discover/manuscripts/hebrew-manuscripts/itempage?docId=PNX_MANUSCRIPTS990031594990205171&vid=MANUSCRIPTS Seder Sefireat HaOmer], Amsterdam, [[1795]], Ktiv project, National Library of Israel |

||

* [https://www.nli.org.il/he/discover/manuscripts/hebrew-manuscripts/itempage?docId=PNX_MANUSCRIPTS990001719450205171&vid=MANUSCRIPTS |

* [https://www.nli.org.il/he/discover/manuscripts/hebrew-manuscripts/itempage?docId=PNX_MANUSCRIPTS990001719450205171&vid=MANUSCRIPTS Kavanot for the Counting of the Omer], Amsterdam, 18th century, Ktiv project, National Library of Israel |

||

* [https://www.nli.org.il/he/discover/manuscripts/hebrew-manuscripts/itempage?docId=PNX_MANUSCRIPTS990034657900205171&vid=MANUSCRIPTS |

* [https://www.nli.org.il/he/discover/manuscripts/hebrew-manuscripts/itempage?docId=PNX_MANUSCRIPTS990034657900205171&vid=MANUSCRIPTS Kabbalist Seder of the Counting of the Omer], [[1782]], [[Italy]], Ktiv project, National Library of Israel |

||

{{Jewish and Israeli holidays}} |

{{Jewish and Israeli holidays}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Iyar observances]] |

[[Category:Iyar observances]] |

||

| Counting of the Omer | |

|---|---|

Omer Calendar

| |

| Observed by | Jews (In various forms also by: Samaritans; Messianic Jews and other Christians, some groups claiming affiliation with Israelites) |

| Type | Jewish and Samaritan, religious |

| Begins | 16 Nisan |

| Ends | 5 Sivan |

| 2023 date | Sunset, 6 April – nightfall, 25 May |

| 2024 date | Sunset, 23 April – nightfall, 11 June |

| 2025 date | Sunset, 13 April – nightfall, 1 June |

| 2026 date | Sunset, 2 April – nightfall, 21 May |

| Related to | Passover, Shavuot |

Counting of the Omer (Hebrew: סְפִירַת הָעוֹמֶר, Sefirat HaOmer, sometimes abbreviated as Sefira) is a ritual in Judaism. It consists of a verbal counting of each of the 49 days between the holidays of Passover and Shavuot. The period of 49 days is known as the "omer period" or simply as "the omer" or "sefirah".[1]

The count has its origins in the biblical command of the Omer offering (or sheaf-offering), which was offered on Passover, and after which 49 days were counted, and the Shavuot holiday was observed. Since the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, the Temple sacrifices are no longer offered, but the counting until Shavuot is still performed. Shavuot is the only major Jewish holiday for which no calendar date is specified in the Torah; rather, its date is determined by the omer count.[1]

The Counting of the Omer begins on the second day of Passover (the 16th of Nisan) for Rabbinic Jews (Orthodox, Conservative, Reform), and after the weekly Shabbat during Passover for Karaite Jews. According to all practices, the 49-day count ends the day before Shavuot, which is the 'fiftieth day' of the count.

The omer ("sheaf") is an old Biblical measure of volume of unthreshed stalks of grain, the amount of grain used for the Temple offering.

The commandment for counting the Omer is recorded within the Torah in Leviticus 23:9–21:

When ye are come into the land which I give unto you, and shall reap the harvest thereof, then ye shall bring the sheaf (omer) of the first-fruits of your harvest unto the priest. And he shall wave the sheaf before the LORD, to be accepted for you; on the morrow after the day of rest the priest shall wave it. ... And ye shall count unto you from the morrow after the day of rest, from the day that ye brought the sheaf of the waving; seven weeks shall there be complete; even unto the morrow after the seventh week shall ye number fifty days; and ye shall present a new meal-offering unto the LORD. ... And ye shall make proclamation on the selfsame day; there shall be a holy convocation unto you; ye shall do no manner of servile work; it is a statute for ever in all your dwellings throughout your generations.

As well as in Deuteronomy 16:9–12:

Seven weeks shalt thou number unto thee; from the time the sickle is first put to the standing corn shalt thou begin to number seven weeks. And thou shalt keep the feast of weeks unto the LORD thy God...

The obligation in post-Temple destruction times is a matter of dispute, as the Temple offerings which depend on the omer count are no longer offered. While Rambam (Maimonides) suggests that the omer count obligation is still biblical, most other commentaries assume that it is of a rabbinic origin in modern times.[2]

As soon as it is definitely night (approximately thirty minutes after sundown), the one who is counting the Omer recites this blessing:

Barukh atah, A-donai E-loheinu, Melekh Ha-ʿolam, asher qid'shanu b'mitzvotav v'tzivanu ʿal S'firat Ha-ʿomer.

Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the Universe, Who has sanctified us with His commandments and commanded us to count the Omer.

Then he or she states the Omer-count in terms of both total days and weeks and days. For example:

The wording of the count differs slightly between customs: the last Hebrew word is either laomer (literally "to the omer") or baomer (literally "in the omer"). Both customs are valid according to halakha.[3]

The count is generally in Hebrew; it may also be counted in any language, however one must understand what one is saying.[4]

The counting is preferably done at night, at the beginning of the Jewish day. If one realizes the next morning or afternoon that they have not yet counted, the count may still be made, but without a blessing. If one forgets to count a day altogether, he or she may continue to count succeeding days, but without a blessing.[5]

In the rabbinic chronology, the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai happened on Shavuot. Thus, the omer period is one of preparation and anticipation for the giving of the Torah.[6] According to Aruch HaShulchan, already in Egypt Moses announced to the Israelites that they would celebrate a religious ceremony at Mount Sinai once 50 days had passed, and the people was so excited by this that they counted the days until that ceremony took place. Homiletically, in modern times when the Temple sacrifices of Shavuot are not offered, counting the omer still has a purpose as a remembrance of the counting up to Sinai.[7]

One explanation for the Counting of the Omer is that it shows the connection between Passover and Shavuot. The physical freedom that the Hebrews achieved at the Exodus from Egypt was only the beginning of a process that climaxed with the spiritual freedom they gained at the giving of the Torah on Shavuot. The Sefer HaChinuch states that the Israelites were only freed from Egypt at Passover in order to receive the Torah.[8] The Counting of the Omer demonstrates how much a Jew desires to accept the Torah in their own life.

According to Maharal, there is a symbolic contrast between the omer offering (offered on Passover) and the Shavuot sacrifice (shtei halechem) offered upon conclusion of the omer. The former consists of barley, which is typically an animal food, and represents the low and passive spiritual level of the Israelites immediately upon leaving Egypt; while the latter consists of wheat and represents the high and active spiritual level of the Israelites upon receiving the Torah.[9]

In Israel, the omer period coincides with the final ripening period of wheat before it is harvested around Shavuot. In this period, the quality of the harvest is very sensitive, and can easily be ruined by bad weather.[10] Thus, the omer period stresses human vulnerability and dependence on God.[11]

According to Nahmanides, Passover and Shavuot effectively form one extended holiday, with the seven weeks of the omer paralleling the seven days of Passover or Sukkot, and the omer period paralleling Chol Hamoed.[12]

Karaite Jews and Israelite Samaritans begin counting the Omer on the day after the weekly Sabbath during Passover, rather than on the second day of Passover (the 16th of Nisan).

This is due to differing interpretations of Leviticus 23:15–16, where the Torah says to begin counting from the "morrow after the day of rest".[13] Rabbinic Jews interpret the "day of rest" to be the first day of Passover, while Karaites and Samaritans understand it to be the first weekly Sabbath that falls during Passover. Thus, the Karaite and Samaritan Shavuot is always on a Sunday, although the actual Hebrew date varies (which complements the fact that a specific date is never given for Shavuot in the Torah, the only holiday for which this is the case).[14][15][16] Historically, Karaite and Karaite-adjacent religious leaders such as Anan ben David, Benjamin Nahawandi, Muhammad ibn Isma'il, Musa of Tiflis (founder of a 9th-century Jewish movement in Babylon); and Malik al Ramli (founder of a 9th-century Jewish movement in the Land of Israel) concluded that Shavuot should fall out on a Sunday.[17] This is also the opinion of Catholics[18] and the historical Sadducees and Boethusians.

The counting of Karaite and Rabbinic Jews coincides when the first day of Passover is on the Sabbath. Samaritan Judaism has an additional difference: because the date of the Samaritan Passover usually differs from the Jewish one by approximately one lunar month,[19] the Karaite and Samaritan counting rarely coincides, despite each beginning on a Sunday.

Ethiopian Jews traditionally had yet another practice: they interpreted the "day of rest" to be the last day of Passover, rather than being the first day (as in rabbinic tradition) or else the Sabbath (as for Karaites).

"Omer-counters" (לוּחַ סְפִירָת הָעוֹמֶר) are devices which aid in remembering the correct day of the omer count. They are often on display in synagogues for the benefit of worshippers who count the Omer with the congregation at the conclusion of evening services. Omer-counters come in varying forms such as:

Reminders to count the Omer are also produced for tablet computers and via SMS for mobile phones.

An omer counter from the 19th century in Lancaster, Pennsylvania is preserved at the Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies.[20]

The omer period has developed into a time of semi-mourning in Jewish custom.

Traditionally, the mourning is in memory of the death of Rabbi Akiva's 24,000 students, as described in the Talmud.[21] (According to the Talmud they died in a "plague" as punishment for not honoring one another properly, but the Sephardic manuscript of Iggeret of Rabbi Sherira Gaon describes them as dying due to "persecution" (shmad), and based on this some modern scholars have suggested that they died in the Bar Kokhba revolt.[22]) Rabbi Yechiel Michel Epstein (author of Aruch HaShulchan) postulates that the mourning period also memorializes Jews who were murdered during the Crusades, pogroms, and blood libels that occurred in Europe.[23] The observance of mourning customs was strengthened after the Rhineland massacres and Cossack riots which occurred in the Omer period.[24] In modern times, the Holocaust is generally included among those events which are memorialized, in particular Yom HaShoah is observed during the Omer.[25]

Mourning practices are observed for only part of the Omer period, with different communities observing different parts. Some families listen to music during the week of Passover and then commence the period of mourning until Lag BaOmer. Some Sephardic Jewish families begin the period of mourning from the first day of the Hebrew month of Iyar and continue for 33 days until the third of Sivan. The custom among Jerusalemites (minhag Yerushalmi) is to follow the mourning practices during the entire Counting of the Omer, save for the day of Lag BaOmer and the last three days of the counting (sheloshet yemei hagbalah) prior to the onset of Shavuot. Many Religious Zionists suspend some or all of the mourning customs on Yom Ha'atzmaut (Israel's Independence Day). The extent of mourning is also based heavily on family custom, and therefore Jews will mourn to different degrees.

Lag BaOmer, the thirty-third day of the Omer, is considered to be the day on which the students stopped dying, so all the rules of mourning are lifted. Some Sephardi Jews, however, continue the mourning period up until the 34th day of the Omer, which is considered by them to be the day of joy and celebration. Spanish and Portuguese Jews do not observe these customs.

During the days of mourning, custom generally forbids haircuts, shaving, listening to instrumental music, or conducting weddings, parties, and dinners with dancing.[26] Some religious Jews shave each Friday afternoon during the mourning period of the Omer in order to be neat in honor of the Shabbat, and some men do so in order to appear neat in their places of employment.

According to some Rishonim, it is the day on which the plague that killed Rabbi Akiva's 24,000 disciples came to an end, and for this reason the mourning period of Sefirat HaOmer concludes on Lag BaOmer in many communities.[27]

According to modern kabbalistic tradition, this day is the CelebrationofSimeon ben Yochai and/or the anniversary of his death. According to a late-medieval tradition, Simeon ben Yochai is buried in Meron, and this association has spawned several well-known customs and practices on Lag BaOmer, including the lighting of bonfires and pilgrimages to Meron.[28]

The period of the counting of the Omer is considered to be a time of potential for inner growth—for a person to work on one's good characteristics (middot) through reflection and development of one aspect each day for the 49 days of the counting.

InKabbalah, each of the seven weeks of the Omer-counting is associated with one of the seven lower sefirot (Chesed, Gevurah, Tiferet, Netzach, Hod, Yesod, Malkuth). Similarly, each day of each week is associated with one of these same seven sefirot, creating forty-nine permutations. The first day of the Omer is therefore associated with "chesed that is in chesed" (loving kindness within loving kindness), the second day with "gevurah that is in chesed" (might within loving kindness); the first day of the second week is associated with "chesed that is in gevurah" (loving-kindness within might), the second day of the second week with "gevurah that is in gevurah" (might within might), and so on.

Symbolically, each of these 49 permutations represents an aspect of each person's character that can be improved or further developed. Recent books which present these 49 permutations as a daily guide to personal character growth have been published by Rabbi Simon Jacobson[29][30] and Rabbi Yaacov Haber and David Sedley.[31][32] The work Counting the Omer: A Kabbalistic Meditation Guide[33] includes meditations, activities and kavvanot (proper mindset) for each of the kabbalistic four worlds for each of the 49 days.

The 49-day period of counting the Omer is also a conducive time to study the teaching of the MishnahinPirkei Avot 6:6, which enumerates the "48 ways" by which Torah is acquired. Rabbi Aharon Kotler (1891–1962) explains that the study of each "way" can be done on each of the first forty-eight days of the Omer-counting; on the forty-ninth day, one should review all the "ways."[34]

|

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

Israeli ethnic |

| ||||||||

| Hebrew months |

| ||||||||

| |||||||||

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|