|

m Dating maintenance tags: {{Cn}}

|

→Procedural nature: spec from a country with hearings

|

||

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

The Convention provides that all contracting states, as well as any judicial and administrative bodies of those contracting states, "shall act expeditiously in all proceedings seeking the return of children",<ref>Hague Convention, Article 11.</ref> and the institutions in each Contracting State "shall use the most expeditious procedures available" to ensure the prompt return specified in the Convention objectives.<ref>Hague Convention, Article 2.</ref> |

The Convention provides that all contracting states, as well as any judicial and administrative bodies of those contracting states, "shall act expeditiously in all proceedings seeking the return of children",<ref>Hague Convention, Article 11.</ref> and the institutions in each Contracting State "shall use the most expeditious procedures available" to ensure the prompt return specified in the Convention objectives.<ref>Hague Convention, Article 2.</ref> |

||

* As a result of the articles on expeditiousness, most{{cn|date=November 2023}} Contracting States conduct [[Hearing (law)|hearings]] with only [[affidavit]] or written evidence, although oral evidence and [[Cross-examination|cross examination]] are allowed if [[credibility]] is at issue,<ref>Katsigiannis v. Kottick-Katsigiannis, 2001 CanLII 24075 (ON CA), <https://canlii.ca/t/1fbr0>.</ref> or if the affidavit evidence is conflicting.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web |title=INCADAT {{!}} Re W. (Abduction: Procedure) [1995] 1 FLR 878 |url=https://www.incadat.com/en/case/37 |access-date=2023-11-06 |website=www.incadat.com}}</ref> In Canada, Convention applications are "typically heard on affidavit evidence".<ref>Katsigiannis v. Kottick-Katsigiannis, 2001 CanLII 24075 (ON CA), <<nowiki>https://canlii.ca/t/1fbr0</nowiki>> at para 59.</ref> The same is true in the United Kingdom,<ref name=":0" /> Finland,<ref>{{Cite web |title=INCADAT {{!}} Supreme Court of Finland: KKO:2004:76 |url=https://www.incadat.com/en/case/839 |access-date=2023-11-06 |website=www.incadat.com}}</ref> and South Africa.<ref>{{Cite web |title=INCADAT {{!}} Central Authority v. H. 2008 (1) SA 49 (SCA) |url=https://www.incadat.com/en/case/900 |access-date=2023-11-06 |website=www.incadat.com}}</ref> |

* As a result of the articles on expeditiousness, most{{cn|date=November 2023}} Contracting States conduct [[Hearing (law)|hearings]] with only [[affidavit]] or written evidence, although oral evidence and [[Cross-examination|cross examination]] are allowed if [[credibility]] is at issue,<ref>Katsigiannis v. Kottick-Katsigiannis, 2001 CanLII 24075 (ON CA), <https://canlii.ca/t/1fbr0>.</ref> or if the affidavit evidence is conflicting.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web |title=INCADAT {{!}} Re W. (Abduction: Procedure) [1995] 1 FLR 878 |url=https://www.incadat.com/en/case/37 |access-date=2023-11-06 |website=www.incadat.com}}</ref> In Canada, Convention applications are "typically heard on affidavit evidence".<ref>Katsigiannis v. Kottick-Katsigiannis, 2001 CanLII 24075 (ON CA), <<nowiki>https://canlii.ca/t/1fbr0</nowiki>> at para 59.</ref> The same is true in the United Kingdom,<ref name=":0" /> Finland,<ref>{{Cite web |title=INCADAT {{!}} Supreme Court of Finland: KKO:2004:76 |url=https://www.incadat.com/en/case/839 |access-date=2023-11-06 |website=www.incadat.com}}</ref> and South Africa.<ref>{{Cite web |title=INCADAT {{!}} Central Authority v. H. 2008 (1) SA 49 (SCA) |url=https://www.incadat.com/en/case/900 |access-date=2023-11-06 |website=www.incadat.com}}</ref> In the Netherlands however 2 hearings (as well as child interview if the child is above 6 years old) within 4 weeks take place in the latter of which presence of all parties is "highly desirable".<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.rechtspraak.nl/Onderwerpen/Internationale-kinderontvoering/Paginas/procedure.aspx#56d1aa0c-bb02-499c-b908-829fb5c9a2c1a5ccaeb8-732a-4d06-876e-6c30a0b9008e7|work=rechtspraak.nl|title=Internationale kinderontvoering|access-date=6 November 2023}}</ref> |

||

==Wrongful removal or retention== |

==Wrongful removal or retention== |

||

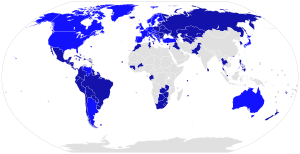

| Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction | |

|---|---|

State parties to the convention

states that signed and ratified the convention

states that acceded to the convention

state that ratified, but convention has not entered into force

| |

| Signed | 25 October 1980 (1980-10-25) |

| Location | The Hague, Netherlands |

| Effective | 1 December 1983[1] |

| Condition | 3 ratifications |

| Parties | 103 (November 2022)[1] |

| Depositary | Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of the Netherlands |

| Languages | French and English |

| Full text | |

The Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child AbductionorHague Abduction Convention is a multilateral treaty that provides an expeditious method to return a child who was wrongfully taken by a parent from one country to another country. In order for the Convention to apply, both countries (the one the child was removed from, and the one the child has been brought to) must be “Contracting States”, i.e. both must have adopted the Convention.[2]

The Convention seeks to address "international child abduction" arising when a child is removed by one parent, when both parents having custody rights or custody has yet to be determined. It was drafted to ensure the prompt return of children wrongfully abducted from their country of habitual residence, or wrongfully retained in a country that is not their country of habitual residence.[3]

The Convention was developed by the Hague Conference on Private International Law (HCCH). The convention was concluded 25 October 1980 and entered into force between the signatories on 1 December 1983.

As 2022, there are 103 parties to the convention; Botswana and Cape Verde being the last countries to accede, in 2022.[4]

The objectives of the Convention are set out in Article 1: to secure the prompt return of children wrongfully removed to or retained in any Contracting State; and, to ensure that rights of custody and of access under the law of one Contracting State are effectively respected in the other Contracting State.[5]

The Convention is used when one parent (referred to as the "abducting parent") allegedly removed or retained the child in a State other than the State of habitual residence, either:

The Convention, by returning children to the State of habitual residence, deters parents from crossing international borders in search of a more sympathetic court (i.e. one who is more likely to rule on custody and access in their favour).

In order for a court to order the return of a child under Article 12 of the Convention,[6] these conditions must be met:

Even if the above conditions are met, the court might not order the return of the child because of the exceptions specified in Articles 12 and 13.

The Convention does not alter any substantive rights of the parents. When an abduction occurs, the parent seeking the child's return will commence proceedings by making an application to the Central Authority. Each Contracting State is required to have a Central Authority to help facilitate the child's return.[10]

The Convention requires that no judicial or administrative authority in the State the child has been brought to shall decide the merits of custody or access until it has been determined that the child is not to be returned under the Convention.[12]

A court in the State the child has been brought to should not consider the merits of the underlying custody or access dispute, but should determine only the country in which that dispute should be adjudicated.

The Convention provides that all contracting states, as well as any judicial and administrative bodies of those contracting states, "shall act expeditiously in all proceedings seeking the return of children",[13] and the institutions in each Contracting State "shall use the most expeditious procedures available" to ensure the prompt return specified in the Convention objectives.[14]

The Convention provides that the removal or retention of a child is "wrongful" whenever:

(a) it is in breach of rights of custody attributed to a person, an institution or any other body, either jointly or alone, under the law of the State in which the child was habitually resident immediately before the removal or retention; and (b) at the time of removal or retention those rights were actually exercised, either jointly or alone, or would have been so exercised but for the removal or retention.[21]

Habitual residence must be assessed first because whether or not a parent had rights of custody is determined by the law of the place of habitual residence. (See, for example the U.S. case Carrascosa v. McGuire, 520 F.3d 249 (3rd Cir. 2008), where the court refused to accept a Spanish court's decision that the father did not have rights of custody. The Spanish courts never applied New Jersey law despite acknowledging that the child's place of habitual residence was New Jersey).

An application for the return of a child can succeed only if a child was, immediately before the alleged removal or retention, habitually resident in the Contracting State to which return is sought.[22] This means that a child, taken from State A to State B, will only be subject to a return order to State A if the court determines that the child’s habitual residence was State A at the time the child was taken.

The Convention does not define the term "habitual residence", so it is open to the courts in each Contracting State to do so. It is intended to be a fact-based determination, avoiding legal technicalities.[23]

There are a few approaches to assessing habitual residence, depending on the court seized of the analysis.

Rights of custody may arise by operation of law or from a judicial or administrative decision, or an agreement having legal effect under the law of the country of habitual residence.[21] The explanatory report of the convention clarifies the meaning of wrongful as:

"the removal of a child by one of the joint holders without the consent of the other, is ... wrongful, and this wrongfulness derives in this particular case, not from some action in breach of a particular law, but from the fact that such action has disregarded the rights of the other parent which are also protected by law, and has interfered with their normal exercise."[38]

The Convention specifies that “rights of custody” includes rights relating to the care of the child and the right to determine the child’s place of residence, while “rights of access” includes the right to take the child for a period of time.[39]

After assessing whether the parent had rights of custody or access according to the laws of the child's state of habitual residence, the court then determines whether or not those rights were “actually exercised”, making the removal or retention wrongful.

Article 15 of the Convention is designed to promote cooperation amongst Contracting States. It provides that a Contracting State may, prior to making an order for the return of the child, request a decision or determination that the removal or retention was wrongful within the meaning of Article 3 of the Convention by that Contracting State’s law.[40] The rationale behind Article 15 is that the foreign court is better placed to understand the meaning and effect of its own laws.[41]

Most Contracting States take the position that an Article 15 determination should report only on matters of national law regarding rights of custody, and not to extend the analysis to classify the removal as wrongful, which is a question for the court requesting the Article 15 determination.[42] An Article 15 determination from a Contracting State should be taken as conclusive to avoid further delays.[41]

The Convention provides special rules for admission and consideration of evidence independent of the evidentiary standards set by any member nation. Article 30 provides that the Application for Assistance, as well as any documents attached to that application or submitted to or by the Central Authority are admissible in any proceeding for a child's return.[43] The convention also provides that no member nation can require legalization or other similar formality of the underlying documents in context of a Convention proceeding.[44] Furthermore, the court in which a Convention action is proceeding "may take notice directly of the law of, and of judicial or administrative decisions, formally recognized or not in the State of habitual residence of the child, without recourse to the specific procedures for the proof of that law or for the recognition of foreign decisions which would otherwise be applicable" when determining whether there is a wrongful removal or retention under the convention.[45]

The Convention limits the defenses against return of a wrongfully removed or retained child. To defend against the return of the child, the defendant must establish to the degree required by the applicable standard of proof (generally determined by the lex fori, i.e. the law of the state where the court is located):

(a) that Petitioner was not "actually exercising custody rights at the time of the removal or retention" under Article 3; or

(b) that Petitioner "had consented to or acquiesced in the removal or retention" under Article 13; or

(c) that more than one year has passed from the time of wrongful removal or retention until the date of the commencement of judicial or administrative proceedings, and the child has "settled in its new environment", under Article 12;

(d) that the child is old enough and has a sufficient degree of maturity to knowingly object to being returned to the Petitioner and that it is appropriate to heed that objection, under Article 13; or

(e) that "there is grave risk that the child's return would expose the child to physical or psychological harm or otherwise place the child in an intolerable situation," under Article 13(b); or

(f) that return of the child would subject the child to violation of basic human rights and fundamental freedoms, under Article 20.

The best interests of the child plays a limited role in deciding an application made under the convention. In X v. Latvia,[46] a Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights decision noted by the 2017 Special Commission on the Practical Operation of the convention, the court stated that "the concept of the best interests of the child must be evaluated in light of the exceptions provided for by the Convention, which concerns the passage of time (Article 12), the conditions of application of the Convention (Article 13 (a)) and the existence of a 'grave risk' (Article 13 (b)), and compliance with the fundamental principles of the requested State on the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms (Article 20)."[47]

InX v. Latvia,[48] the Grand Chamber[clarification needed] held that the parent who opposes the return of a child on the basis of Article 13(b) exception must adduce sufficient evidence of the existence of a risk that can be specifically described as "grave". Further, as held by the Grand Chamber, while Article 13(b) contemplates "grave risk" to entail not only "physical or psychological harm", but also "an intolerable situation", such situation does not include the inconveniences necessarily linked to the experience of return, but only situations which goes beyond what a child might reasonably bear.[49]

As of November 2022, there are 103 parties to the Convention.[4] The last states to accede to the convention were Botswana and Cape Verde in 2022.[4]

Contracting states that have enacted domestic legislation to give effect to the Convention include:

| Authority control databases: National |

|

|---|