|

→top: rm {{BLP sources}}; comparing article to its state in June 2021, the issue appears to have been addressed

|

Tighten.

|

||

| (20 intermediate revisions by 14 users not shown) | |||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''John Warnock Hinckley Jr.''' (born May 29, 1955) is an American <!-- Adding "American musician" to this lead section is undue. He was not known as a musician at the time of the attempted assassination; see talk page --> who [[Attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan|attempted to assassinate]] U.S. President [[Ronald Reagan]] as he left the [[Washington Hilton|Hilton Hotel]] in Washington, D.C., on March 30, 1981, two months after [[First inauguration of Ronald Reagan|Reagan's first inauguration]]. Using a revolver, Hinckley wounded Reagan, the police officer [[Thomas Delahanty]], the [[United States Secret Service|Secret Service]] agent [[Tim McCarthy]] and the [[White House Press Secretary]], [[James Brady]]. Brady was left disabled and eventually died from his injuries. |

'''John Warnock Hinckley Jr.''' (born May 29, 1955) is an American man<!-- Adding "American musician" to this lead section is undue. He was not known as a musician at the time of the attempted assassination; see talk page --> who [[Attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan|attempted to assassinate]] U.S. President [[Ronald Reagan]] as he left the [[Washington Hilton|Hilton Hotel]] in Washington, D.C., on March 30, 1981, two months after [[First inauguration of Ronald Reagan|Reagan's first inauguration]]. Using a revolver, Hinckley wounded Reagan, the police officer [[Thomas Delahanty]], the [[United States Secret Service|Secret Service]] agent [[Tim McCarthy]] and the [[White House Press Secretary]], [[James Brady]]. Brady was left disabled and eventually died from his injuries. |

||

Hinckley was reportedly seeking fame to impress the actress [[Jodie Foster]], with whom he had a fixation. He was found [[Insanity defense|not guilty by reason of insanity]] and remained under institutional psychiatric care for over three decades.<ref name="foxnews.com">{{cite news|url=https://www.foxnews.com/us/john-hinckley-jr-leaves-dc-mental-hospital-for-virginia|title=John Hinckley Jr. to begin living full-time in Virginia Sept. 10|date=September 12, 2016|access-date=December 6, 2018|agency=[[Fox News]]|archive-date=December 6, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181206145254/https://www.foxnews.com/us/john-hinckley-jr-leaves-dc-mental-hospital-for-virginia|url-status=live}}</ref> Public outcry over the verdict led state legislatures and Congress to narrow their respective insanity defenses. |

Hinckley was reportedly seeking fame to impress the actress [[Jodie Foster]], with whom he had a fixation. He was found [[Insanity defense|not guilty by reason of insanity]] and remained under institutional psychiatric care for over three decades.<ref name="foxnews.com">{{cite news|url=https://www.foxnews.com/us/john-hinckley-jr-leaves-dc-mental-hospital-for-virginia|title=John Hinckley Jr. to begin living full-time in Virginia Sept. 10|date=September 12, 2016|access-date=December 6, 2018|agency=[[Fox News]]|archive-date=December 6, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181206145254/https://www.foxnews.com/us/john-hinckley-jr-leaves-dc-mental-hospital-for-virginia|url-status=live}}</ref> Public outcry over the verdict led state legislatures and Congress to narrow their respective insanity defenses. |

||

In 2016, a federal judge ruled that Hinckley could be released from psychiatric care as he was no longer considered a threat to himself or others, albeit with many conditions. After 2020, a ruling was issued that Hinckley may showcase his artwork, writings, and music publicly under his own name, rather than anonymously as he had in the past. Since then, he has maintained a [[YouTube]] channel for his music. His restrictions were unconditionally lifted in June 2022 |

In 2016, a federal judge ruled that Hinckley could be released from psychiatric care as he was no longer considered a threat to himself or others, albeit with many conditions. After 2020, a ruling was issued that Hinckley may showcase his artwork, writings, and music publicly under his own name, rather than anonymously as he had in the past. Since then, he has maintained a [[YouTube]] channel for his music. His restrictions were unconditionally lifted in June 2022. |

||

== Early life == |

== Early life == |

||

John Warnock Hinckley Jr. was born in [[Ardmore, Oklahoma]],<ref name=UMKC>{{cite web |url=http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/hinckley/HBIO.HTM |title=John W. Hinckley Jr.: A Biography |publisher=[[University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law]] |access-date=September 19, 2013 |archive-date=March 14, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110314081410/http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/hinckley/HBIO.HTM |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>[http://www.cnn.com/2013/03/20/us/john-hinckley-jr-fast-facts/index.html "John Hinckley Jr Fast Facts"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170606141228/http://www.cnn.com/2013/03/20/us/john-hinckley-jr-fast-facts/index.html |date=June 6, 2017 }}. [[CNN]]. Retrieved September 19, 2013.</ref> and moved with his wealthy family to [[Dallas, Texas]], at the age of four. His father was John Warnock Hinckley (1925–2008), founder, chairman, chief executive and president of the Vanderbilt Energy Corporation.<ref>{{cite news |title=Vanderbilt Recovers from Shock of Link to Reagan Shooting|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1981/04/04/business/vanderbilt-recovers-from-shock-of-link-to-regan-shooting.html |access-date=October 24, 2022 |work=The New York Times |date=April 4, 1981}}</ref> His mother was Jo Ann Hinckley ([[ |

John Warnock Hinckley Jr. was born in [[Ardmore, Oklahoma]],<ref name=UMKC>{{cite web |url=http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/hinckley/HBIO.HTM |title=John W. Hinckley Jr.: A Biography |publisher=[[University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law]] |access-date=September 19, 2013 |archive-date=March 14, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110314081410/http://law2.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/hinckley/HBIO.HTM |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>[http://www.cnn.com/2013/03/20/us/john-hinckley-jr-fast-facts/index.html "John Hinckley Jr Fast Facts"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170606141228/http://www.cnn.com/2013/03/20/us/john-hinckley-jr-fast-facts/index.html |date=June 6, 2017 }}. [[CNN]]. Retrieved September 19, 2013.</ref> and moved with his wealthy family to [[Dallas, Texas]], at the age of four. His father was John Warnock Hinckley (1925–2008), founder, chairman, chief executive and president of the Vanderbilt Energy Corporation.<ref>{{cite news |title=Vanderbilt Recovers from Shock of Link to Reagan Shooting|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1981/04/04/business/vanderbilt-recovers-from-shock-of-link-to-regan-shooting.html |access-date=October 24, 2022 |work=The New York Times |date=April 4, 1981}}</ref> His mother was Jo Ann Hinckley ([[Birth names#Maiden and married names|née]] Moore; 1925–2021). |

||

Hinckley grew up in [[University Park, Texas]],<ref name=AmericanExperience>{{cite web|author=Wolf, Julie|url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography/reagan-hinckley/|title=Biography: John Hinckley Jr.|work=[[American Experience|The American Experience]]|publisher=[[PBS]]|access-date=September 19, 2013|archive-date=February 13, 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110213093714/https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography/reagan-hinckley/|url-status=live}}</ref> and attended [[Highland Park High School (University Park, Texas)|Highland Park High School]]<ref>{{cite news|title=John Hinckley Jr. brings infamy to Lubbock|url=http://www.lubbockcentennial.com/Section/1959_1983/hinckley.shtml|year=2008|newspaper=[[Lubbock Avalanche-Journal]]|access-date=August 5, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130925143644/http://www.lubbockcentennial.com/Section/1959_1983/hinckley.shtml|archive-date=September 25, 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref> in [[Dallas County, Texas|Dallas County]]. After Hinckley graduated from high school in 1973, his family, owners of the Hinckley oil company, moved to [[Evergreen, Colorado]], where the new company headquarters was located.<ref name="UMKC" /> He was an off-and-on student at [[Texas Tech University]] from 1974 to 1980 but eventually dropped out.<ref>{{Cite book|author=Texas Tech University|date=1974|title=La Ventana, vol. 049|language=en|hdl=2346/48660}}</ref> In 1975, he went to Los Angeles in the hope of becoming a songwriter. His efforts were unsuccessful, and he wrote to his parents with tales of misfortune and pleas for money. He also spoke of a girlfriend, Lynn Collins, who turned out to be a fabrication. In September 1976, he returned to his parents' home in Evergreen.<ref name="Noe">{{cite web|first=Denise|last=Noe|url=https://www.crimelibrary.org/terrorists_spies/assassins/john_hinckley/1.html|title=The John Hinckley Case|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130517070711/http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/terrorists_spies/assassins/john_hinckley/9.html|archive-date=May 17, 2013|access-date=September 19, 2013|url-status=live|website=[[Crime Library]]}}</ref>{{rp|4}} In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Hinckley began purchasing weapons and practicing with them. He was prescribed |

Hinckley grew up in [[University Park, Texas]],<ref name=AmericanExperience>{{cite web|author=Wolf, Julie|url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography/reagan-hinckley/|title=Biography: John Hinckley Jr.|work=[[American Experience|The American Experience]]|publisher=[[PBS]]|access-date=September 19, 2013|archive-date=February 13, 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110213093714/https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography/reagan-hinckley/|url-status=live}}</ref> and attended [[Highland Park High School (University Park, Texas)|Highland Park High School]]<ref>{{cite news|title=John Hinckley Jr. brings infamy to Lubbock|url=http://www.lubbockcentennial.com/Section/1959_1983/hinckley.shtml|year=2008|newspaper=[[Lubbock Avalanche-Journal]]|access-date=August 5, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130925143644/http://www.lubbockcentennial.com/Section/1959_1983/hinckley.shtml|archive-date=September 25, 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref> in [[Dallas County, Texas|Dallas County]]. After Hinckley graduated from high school in 1973, his family, owners of the Hinckley oil company, moved to [[Evergreen, Colorado]], where the new company headquarters was located.<ref name="UMKC" /> He was an off-and-on student at [[Texas Tech University]] from 1974 to 1980 but eventually dropped out.<ref>{{Cite book|author=Texas Tech University|date=1974|title=La Ventana, vol. 049|language=en|hdl=2346/48660}}</ref> In 1975, he went to Los Angeles in the hope of becoming a songwriter. His efforts were unsuccessful, and he wrote to his parents with tales of misfortune and pleas for money. He also spoke of a girlfriend, Lynn Collins, who turned out to be a fabrication. In September 1976, he returned to his parents' home in Evergreen.<ref name="Noe">{{cite web|first=Denise|last=Noe|url=https://www.crimelibrary.org/terrorists_spies/assassins/john_hinckley/1.html|title=The John Hinckley Case|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130517070711/http://www.trutv.com/library/crime/terrorists_spies/assassins/john_hinckley/9.html|archive-date=May 17, 2013|access-date=September 19, 2013|url-status=live|website=[[Crime Library]]}}</ref>{{rp|4}} In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Hinckley began purchasing weapons and practicing with them. He was prescribed [[antidepressant]]s and [[tranquilizer]]s to deal with his emotional problems.<ref name=UMKC /> |

||

== Obsession with Jodie Foster == |

== Obsession with Jodie Foster == |

||

Hinckley became obsessed with the 1976 film ''[[Taxi Driver]]'', in which disturbed protagonist [[Travis Bickle]] ([[Robert De Niro]]) plots to assassinate a presidential candidate. Bickle was partly based on the diaries of [[Arthur Bremer]], who attempted to assassinate [[George Wallace]].<ref name=AmericanExperience /> Hinckley developed an infatuation with [[Jodie Foster]], who played Iris, a sexually trafficked 12-year-old child. Hinckley began to adopt the dress and mannerisms of the Travis Bickle character.<ref name="famoustrials">{{Cite web |last=Linder |first=Douglas |author-link=Doug Linder|title=The Trial of John W. Hinckley, Jr. |url=https://famous-trials.com/johnhinckley/537-home?__cf_chl_tk=FpBcrfEUItcGHJE40s26uuMJWXN8nEjNfUe3GY7mdMs-1711234800-0.0.1.1-1365|publisher=UMKC School of Law|website=famous-trials.com}}</ref> |

Hinckley became obsessed with the 1976 film ''[[Taxi Driver]]'', in which disturbed protagonist [[Travis Bickle]] ([[Robert De Niro]]) plots to assassinate a presidential candidate. Bickle was partly based on the diaries of [[Arthur Bremer]], who attempted to assassinate [[George Wallace]].<ref name=AmericanExperience /> Hinckley developed an infatuation with [[Jodie Foster]], who played Iris, a sexually trafficked 12-year-old child. Hinckley began to adopt the dress and mannerisms of the Travis Bickle character.<ref name="famoustrials">{{Cite web |last=Linder |first=Douglas |author-link=Doug Linder|title=The Trial of John W. Hinckley, Jr. |url=https://famous-trials.com/johnhinckley/537-home?__cf_chl_tk=FpBcrfEUItcGHJE40s26uuMJWXN8nEjNfUe3GY7mdMs-1711234800-0.0.1.1-1365|publisher=UMKC School of Law|website=famous-trials.com}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:Window from the armored limousine that was struck by a bullet during the 1981 assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan and the revolver used by would-be assassin John Hinckley.jpg|right|thumb|Hinkley's [[Röhm RG-14]] pistol that he bought in Dallas; behind it is the armored-glass limousine window hit by one of its bullets. On display at the US Secret Service's restricted-access museum, 2022<ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-12-10 |title=The Secret Washington Museum That Tourists Can't Visit |url=https://www.voanews.com/a/the-secret-washington-museum-that-tourists-can-t-visit-/6866426.html |access-date=2024-03-27 |website=Voice of America |language=en}}</ref>]] |

||

When Foster entered [[Yale University]], Hinckley moved to [[New Haven, Connecticut]] |

When Foster entered [[Yale University]], Hinckley moved to [[New Haven, Connecticut]] for a short time to [[stalking|stalk]] her. His parents had given him $3600 ({{Inflation|US|3600|1980|r=-2|fmt=eq}}) for the purpose of attending a writing course at Yale. He never enrolled on the course, but instead used the money to support himself while sending Foster love letters and romantic poems, and repeatedly calling and leaving her messages.<ref name="famoustrials" /> |

||

| ⚫ | Failing to develop any meaningful contact with Foster, Hinckley fantasized about conducting an [[aircraft hijacking]] or killing himself in front of her to get her attention. Eventually, he settled on a scheme to impress her by assassinating the president, thinking that by achieving a place in history, he would appeal to her as an equal. |

||

| ⚫ | Failing to develop any meaningful contact with Foster, Hinckley fantasized about conducting an [[aircraft hijacking]] or killing himself in front of her to get her attention. Eventually, he settled on a scheme to impress her by assassinating the president, thinking that by achieving a place in history, he would appeal to her as an equal. |

||

Hinckley trailed President [[Jimmy Carter]] from state to state during his campaign for the [[1980 United States presidential election]] and got to within 20 feet of him at a rally at [[Dayton, Ohio]].<ref name="famoustrials" /> On October 9, 1980, he was in [[Nashville, Tennessee]], on the same day Carter was visiting the city. Hinckley was arrested at [[Nashville International Airport]] while trying to board a flight to New York with handcuffs and three unloaded guns in his hand-luggage. The airport police handed him over to the [[Metropolitan Nashville Police Department|Nashville city police]]. Hinckley's guns and handcuffs were confiscated and he was fined $50 plus court costs; he was released later the same day.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Rogers |first=Ed |date=1981-04-08 |title=Hinckley's previous arrest considered minor - UPI Archives |url=https://www.upi.com/Archives/1981/04/08/Hinckleys-previous-arrest-considered-minor/5533355554000/ |access-date=2024-03-22 |website=UPI |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |date=1981-04-05 |title=Agents Tracing Hinckley's Path Find a Shift to Violent Emotion |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1981/04/05/us/agents-tracing-hinckley-s-path-find-a-shift-to-violent-emotion.html |work=New York Times}}</ref> |

Hinckley trailed President [[Jimmy Carter]] from state to state during his campaign for the [[1980 United States presidential election]] and got to within 20 feet of him at a rally at [[Dayton, Ohio]].<ref name="famoustrials" /> On October 9, 1980, he was in [[Nashville, Tennessee]], on the same day Carter was visiting the city. Hinckley was arrested at [[Nashville International Airport]] while trying to board a flight to New York with handcuffs and three unloaded guns in his hand-luggage. The airport police handed him over to the [[Metropolitan Nashville Police Department|Nashville city police]]. Hinckley's guns and handcuffs were confiscated and he was fined $50 plus court costs; he was released later the same day.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Rogers |first=Ed |date=1981-04-08 |title=Hinckley's previous arrest considered minor - UPI Archives |url=https://www.upi.com/Archives/1981/04/08/Hinckleys-previous-arrest-considered-minor/5533355554000/ |access-date=2024-03-22 |website=UPI |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |date=1981-04-05 |title=Agents Tracing Hinckley's Path Find a Shift to Violent Emotion |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1981/04/05/us/agents-tracing-hinckley-s-path-find-a-shift-to-violent-emotion.html |work=New York Times}}</ref> |

||

After Nashville, Hinckley flew to [[Dallas]] |

After Nashville, Hinckley flew to [[Dallas]]. On October 13th he bought more guns from a Dallas pawn shop; they including the [[.22 caliber]] [[Röhm RG-14]] revolver he'd use five months later to attempt the assassination of Reagan.<ref>{{cite news |title=It's Business as Usual at the Shop in Dallas where Hinkley Bought Gun|newspaper=The New York Times |date=August 14, 1981 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1981/04/14/us/it-s-business-as-usual-at-the-shop-in-dallas-where-hinckley-bought-gun.html |last1=Pear |first1=Robert |access-date=2024-06-25 |url-status=live}}</ref> The $3600 from his parents was now exhausted and he returned home penniless.<ref name="famoustrials" /> He spent four months undergoing psychiatric treatment for depression but his mental health did not improve.<ref name="famoustrials" /> He began to target the newly elected president [[Ronald Reagan]] in 1981. For this purpose, he collected material on the [[assassination of John F. Kennedy]]. |

||

== Ronald Reagan assassination attempt == |

== Ronald Reagan assassination attempt == |

||

{{Main|Attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan}} |

{{Main|Attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan}} |

||

| ⚫ |

[[File:Window from the armored limousine that was struck by a bullet during the 1981 assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan and the revolver used by would-be assassin John Hinckley.jpg|right|thumb|[[Röhm RG-14]] |

||

[[File:President Ronald Reagan moments before he was shot in an assassination attempt 1981.jpg|right|thumb|250px|Ronald Reagan waves just before he is shot. From left are Jerry Parr, in a trench coat, who pushed Reagan into the limousine; press secretary James Brady, who was seriously wounded by a gunshot to the head; Reagan; aide Michael Deaver; an unidentified policeman; policeman Thomas K. Delahanty, who was shot in the neck; and secret service agent Tim McCarthy, who was shot in the chest.]] |

[[File:President Ronald Reagan moments before he was shot in an assassination attempt 1981.jpg|right|thumb|250px|Ronald Reagan waves just before he is shot. From left are Jerry Parr, in a trench coat, who pushed Reagan into the limousine; press secretary James Brady, who was seriously wounded by a gunshot to the head; Reagan; aide Michael Deaver; an unidentified policeman; policeman Thomas K. Delahanty, who was shot in the neck; and secret service agent Tim McCarthy, who was shot in the chest.]] |

||

[[File:Photograph of chaos outside the Washington Hilton Hotel after the assassination attempt on President Reagan (white border removed).jpg|right|thumb|Brady and Delahanty lie wounded on the ground]] |

[[File:Photograph of chaos outside the Washington Hilton Hotel after the assassination attempt on President Reagan (white border removed).jpg|right|thumb|Brady and Delahanty lie wounded on the ground]] |

||

Hinckley arrived in Washington DC on March 29, 1981 after travelling by [[Greyhound Lines|Greyhound bus]] from Los Angeles. He spent the night in a hotel. The following morning, he read President Reagan's itinerary in a newspaper and discovered that later that day |

Hinckley arrived in Washington DC on March 29, 1981 after travelling by [[Greyhound Lines|Greyhound bus]] from Los Angeles. He spent the night in a hotel. The following morning, he read President Reagan's itinerary in a newspaper and discovered that later that day Reagan was to be at the [[Washington Hilton|Hilton Hotel]] to address an [[AFL–CIO]] conference. Hinckley spent the morning composing a letter to Jodie Foster.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/hinckley/jfostercommun.HTM|title=Letter written to Jodie Foster by John Hinckley Jr.|publisher=University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law|date=March 30, 1981|access-date=February 8, 2011|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110108054234/http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/hinckley/jfostercommun.HTM|archive-date=January 8, 2011}}</ref> |

||

{{blockquote|Over the past seven months I've left you dozens of poems, letters and love messages in the faint hope that you could develop an interest in me. Although we talked on the phone a couple of times I never had the nerve to simply approach you and introduce myself. ... The reason I'm going ahead with this attempt now is because I cannot wait any longer to impress you. |Excerpt from Hinckley's March 30 letter}} |

{{blockquote|Over the past seven months I've left you dozens of poems, letters and love messages in the faint hope that you could develop an interest in me. Although we talked on the phone a couple of times I never had the nerve to simply approach you and introduce myself. ... The reason I'm going ahead with this attempt now is because I cannot wait any longer to impress you. |Excerpt from Hinckley's March 30 letter}} |

||

After finishing the letter, he took a taxi to the Hilton Hotel.<ref name="famoustrials" /> |

After finishing the letter, he took a taxi to the Hilton Hotel.<ref name="famoustrials" /> |

||

At 2:27 p.m. [[Eastern Time Zone|EST]],<ref name=UMKC /> Hinckley was among a crowd of several hundred outside the hotel |

At 2:27 p.m. [[Eastern Time Zone|EST]],<ref name=UMKC /> Hinckley was among a crowd of several hundred outside the hotel; he was carrying his Röhm revolver. When Reagan emerged from the hotel, Hinckley shot all the gun's six bullets at him. The first shot critically wounded press secretary [[James Brady]]; the second wounded police officer [[Thomas Delahanty]]. The third shot missed, but the fourth hit [[United States Secret Service|Secret Service]] agent [[Tim McCarthy|Timothy McCarthy]], who was deliberately standing in the line-of-fire to shield Reagan. The fifth bullet struck the armoured glass of the [[Presidential state car (United States)|presidential limousine]], but the sixth and last seriously wounded Reagan when it ricocheted off the side of the limousine and hit him in the chest.<ref>{{cite news| last = Reagan| first = Ronald| title = Larry King Live: Remembering the Assassination Attempt on Ronald Reagan| date = March 30, 2001| url = http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0103/30/lkl.00.html| access-date = November 13, 2008| work = CNN| archive-date = December 19, 2019| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20191219043617/http://transcripts.cnn.com/TRANSCRIPTS/0103/30/lkl.00.html| url-status = live}}</ref><ref name="famoustrials" /> |

||

Alfred Antenucci, a [[Cleveland, Ohio]], labor official who stood near Hinckley and saw him firing,<ref name="ssreport19810504">{{Cite web |url=http://www.secretservice.gov/Reagan%20Assassination%20Attempt%20Interview%20Reports.pdf |title=Reagan Assassination Attempt Interview Reports |last=Office of Inspection |publisher=United States Secret Service |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110721062148/https://www.secretservice.gov/Reagan%20Assassination%20Attempt%20Interview%20Reports.pdf |archive-date=July 21, 2011 |access-date=March 11, 2011}}</ref> hit Hinckley in the head and pulled him to the ground.<ref name=antenucciobit>{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1984/05/14/obituaries/alfred-antenucci.html |title=Alfred Antenucci (death notice) |work=The New York Times |agency=Associated Press |date=May 13, 1984 |access-date=December 1, 2010 |archive-date=May 18, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130518111738/http://www.nytimes.com/1984/05/14/obituaries/alfred-antenucci.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Within two seconds, agent Dennis McCarthy (no relation to agent Timothy McCarthy) dove onto Hinckley, intent on protecting Hinckley and to avoid what happened to [[Lee Harvey Oswald]], who was killed before he could be tried for the assassination of President Kennedy.<ref name="wilber2011">{{cite book | title=Rawhide Down: The Near Assassination of Ronald Reagan | author=Wilber, Del Quentin | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PdCLMpSY5qkC&pg=PP1 | year=2011 | publisher=Macmillan | isbn=978-0-8050-9346-9 | format=hardcover }}</ref>{{rp|84}} Another Cleveland-area labor official, Frank J. McNamara, joined Antenucci and started punching Hinckley in the head, striking him so hard he drew blood.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.upi.com/Archives/1981/04/01/Cleveland-labor-leader-ill-after-grabbing-Reagans-attacker/6802354949200/|title=Cleveland labor leader ill after grabbing Reagan's attacker|website=UPI|access-date=July 13, 2019|archive-date=July 13, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190713181156/https://www.upi.com/Archives/1981/04/01/Cleveland-labor-leader-ill-after-grabbing-Reagans-attacker/6802354949200/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

Alfred Antenucci, a [[Cleveland, Ohio]], labor official who stood near Hinckley and saw him firing,<ref name="ssreport19810504">{{Cite web |url=http://www.secretservice.gov/Reagan%20Assassination%20Attempt%20Interview%20Reports.pdf |title=Reagan Assassination Attempt Interview Reports |last=Office of Inspection |publisher=United States Secret Service |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110721062148/https://www.secretservice.gov/Reagan%20Assassination%20Attempt%20Interview%20Reports.pdf |archive-date=July 21, 2011 |access-date=March 11, 2011}}</ref> hit Hinckley in the head and pulled him to the ground.<ref name=antenucciobit>{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1984/05/14/obituaries/alfred-antenucci.html |title=Alfred Antenucci (death notice) |work=The New York Times |agency=Associated Press |date=May 13, 1984 |access-date=December 1, 2010 |archive-date=May 18, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130518111738/http://www.nytimes.com/1984/05/14/obituaries/alfred-antenucci.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Within two seconds, agent Dennis McCarthy (no relation to agent Timothy McCarthy) dove onto Hinckley, intent on protecting Hinckley and to avoid what happened to [[Lee Harvey Oswald]], who was killed before he could be tried for the assassination of President Kennedy.<ref name="wilber2011">{{cite book | title=Rawhide Down: The Near Assassination of Ronald Reagan | author=Wilber, Del Quentin | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PdCLMpSY5qkC&pg=PP1 | year=2011 | publisher=Macmillan | isbn=978-0-8050-9346-9 | format=hardcover }}</ref>{{rp|84}} Another Cleveland-area labor official, Frank J. McNamara, joined Antenucci and started punching Hinckley in the head, striking him so hard he drew blood.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.upi.com/Archives/1981/04/01/Cleveland-labor-leader-ill-after-grabbing-Reagans-attacker/6802354949200/|title=Cleveland labor leader ill after grabbing Reagan's attacker|website=UPI|access-date=July 13, 2019|archive-date=July 13, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190713181156/https://www.upi.com/Archives/1981/04/01/Cleveland-labor-leader-ill-after-grabbing-Reagans-attacker/6802354949200/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

At trial, the government emphasized Hinckley's premeditation of the shooting: noting that he had purchased a gun, trailed President Reagan, traveled to Washington, D.C., left a note detailing his plan, selected particularly devastating ammunition, and fired six shots. The defense, on the other hand, argued that Hinckley's actions and his obsession with Foster indicated that he was legally insane.<ref name="Sallett">{{cite journal|first=Jonathan B.|last=Sallett|title=Review: After Hinckley: The Insanity Defense Reexamined|volume=94|journal=Yale Law Journal|pages=1545–57|year=1985|doi=10.2307/796141 |jstor=796141 |department=Book review|url=https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/160249284.pdf}}</ref>{{rp|1548}} The trial was chiefly devoted to a battle of the psychiatric experts concerning Hinckley's mental state.<ref name="Sallett"/>{{rp|1549}} Because Hinckley was charged in federal court, the prosecution was required to prove his sanity beyond reasonable doubt.<ref>{{cite book|first=Alan A.|last=Stone|title=Law, Psychiatry, and Morality: Essays and Analysis|page=82|year=1984}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|newspaper=[[New York Times]]|first=Stuart|last=Taylor|title=Actress's Testimony Videotaped for Hinckley's Long-Delayed Trial|date=March 31, 1982|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1982/03/31/us/actress-s-testimony-videotaped-for-hinckley-s-long-delayed-trial.html}}</ref> |

At trial, the government emphasized Hinckley's premeditation of the shooting: noting that he had purchased a gun, trailed President Reagan, traveled to Washington, D.C., left a note detailing his plan, selected particularly devastating ammunition, and fired six shots. The defense, on the other hand, argued that Hinckley's actions and his obsession with Foster indicated that he was legally insane.<ref name="Sallett">{{cite journal|first=Jonathan B.|last=Sallett|title=Review: After Hinckley: The Insanity Defense Reexamined|volume=94|journal=Yale Law Journal|pages=1545–57|year=1985|doi=10.2307/796141 |jstor=796141 |department=Book review|url=https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/160249284.pdf}}</ref>{{rp|1548}} The trial was chiefly devoted to a battle of the psychiatric experts concerning Hinckley's mental state.<ref name="Sallett"/>{{rp|1549}} Because Hinckley was charged in federal court, the prosecution was required to prove his sanity beyond reasonable doubt.<ref>{{cite book|first=Alan A.|last=Stone|title=Law, Psychiatry, and Morality: Essays and Analysis|page=82|year=1984}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|newspaper=[[New York Times]]|first=Stuart|last=Taylor|title=Actress's Testimony Videotaped for Hinckley's Long-Delayed Trial|date=March 31, 1982|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1982/03/31/us/actress-s-testimony-videotaped-for-hinckley-s-long-delayed-trial.html}}</ref> |

||

For the defense, [[William T. Carpenter]], who diagnosed Hinckley with [[schizophrenia]], testified for three days, opining that Hinckley had amalgamated various personalities from fiction and real life—including Travis Bickle from ''Taxi Driver'' and [[John Lennon]]. Carpenter concluded that Hinckley could not emotionally appreciate the wrongfulness of his actions because he was consumed by the prospect of a "magical unification with Jodie Foster".<ref name="Famous Trials">{{cite web|first=Douglas O.|last=Linder|author-link=Doug Linder|title=The Trial of John W. Hinckley, Jr.|work=Famous Trials|url=https://www.famous-trials.com/johnhinckley/537-home}}</ref> David Bear testified that Hinckley's actions followed "the very opposite of logic" and that Hinckley did not exhibit signs of [[malingering]].<ref name="Famous Trials"/> Bear said that his opinion was in part supported by a CAT scan of Hinckley's brain showing widened [[Sulcus (neuroanatomy)|sulci]], a feature Bear said was found in {{frac|1|3}} of persons with schizophrenia but only |

For the defense, [[William T. Carpenter]], who diagnosed Hinckley with [[schizophrenia]], testified for three days, opining that Hinckley had amalgamated various personalities from fiction and real life—including Travis Bickle from ''Taxi Driver'' and [[John Lennon]]. Carpenter concluded that Hinckley could not emotionally appreciate the wrongfulness of his actions because he was consumed by the prospect of a "magical unification with Jodie Foster".<ref name="Famous Trials">{{cite web|first=Douglas O.|last=Linder|author-link=Doug Linder|title=The Trial of John W. Hinckley, Jr.|work=Famous Trials|url=https://www.famous-trials.com/johnhinckley/537-home}}</ref> David Bear testified that Hinckley's actions followed "the very opposite of logic" and that Hinckley did not exhibit signs of [[malingering]].<ref name="Famous Trials"/> Bear said that his opinion was in part supported by a CAT scan of Hinckley's brain showing widened [[Sulcus (neuroanatomy)|sulci]], a feature Bear said was found in {{frac|1|3}} of persons with schizophrenia but only two percent of non-schizophrenics.<ref name="Famous Trials"/><ref name="Sallett"/>{{rp|1549}} Similarly, Ernest Prelinger testified that, while Hinckley had an above-average IQ, his results on the [[Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory]] were highly abnormal—specifically, Prelinger said that only one person out of a million with Hinckley's score would not be suffering from serious mental illness.<ref name="Famous Trials"/> |

||

For the prosecution, [[Park Dietz]] testified that he had diagnosed Hinckley with [[dysthymia]] and three types of personality disorders: [[Narcissistic personality disorder|narcissistic]]; [[schizoid personality disorder|schizoid]]; and mixed, with [[Borderline personality disorder|borderline]], and [[Passive-aggressive behavior#Passive-aggressive personality disorder|passive-aggressive]] features.<ref name="Noe"/>{{rp|9}} Dietz found that none of these illnesses rendered Hinckley legally insane;<ref name="Noe"/>{{rp|9}} his report said that there was "no evidence that [Hinckley] was so impaired that he could not appreciate the wrongfulness of his conduct or conform his conduct to the requirements of the law".<ref name="Famous Trials"/> Sally Johnson, a psychiatrist in the federal prison who interviewed Hinckley more than any other doctor, emphasized that Hinckley had planned the shooting<ref>{{cite journal|title=The Semantics of Insanity|first=Gertrude|last=Block|journal=Oklahoma Law Review|volume=36|date=1983|pages=561–612|url=https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2116&context=olr}}</ref>{{rp|601}} and that he was preoccupied with being famous.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.upi.com/Archives/1982/06/11/He-felt-people-owed-him-something/1205392616000/|work=[[United Press International]]|title='He felt people owed him something'|first=Gregory|last=Gordan|date=June 11, 1982}}</ref> Johnson said that Hinckley's interest in Foster was no different than any young man's interest in a movie star.<ref>{{cite news|work=[[United Press International]]|title=A government psychiatrist said John W. Hinckley Jr.'s poems...|url=https://www.upi.com/Archives/1982/06/22/A-government-psychiatrist-said-John-W-Hinckley-Jrs-poems/4417393566400/|date=June 22, 1982}}</ref> |

For the prosecution, [[Park Dietz]] testified that he had diagnosed Hinckley with [[dysthymia]] and three types of personality disorders: [[Narcissistic personality disorder|narcissistic]]; [[schizoid personality disorder|schizoid]]; and mixed, with [[Borderline personality disorder|borderline]], and [[Passive-aggressive behavior#Passive-aggressive personality disorder|passive-aggressive]] features.<ref name="Noe"/>{{rp|9}} Dietz found that none of these illnesses rendered Hinckley legally insane;<ref name="Noe"/>{{rp|9}} his report said that there was "no evidence that [Hinckley] was so impaired that he could not appreciate the wrongfulness of his conduct or conform his conduct to the requirements of the law".<ref name="Famous Trials"/> Sally Johnson, a psychiatrist in the federal prison who interviewed Hinckley more than any other doctor, emphasized that Hinckley had planned the shooting<ref>{{cite journal|title=The Semantics of Insanity|first=Gertrude|last=Block|journal=Oklahoma Law Review|volume=36|date=1983|pages=561–612|url=https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2116&context=olr}}</ref>{{rp|601}} and that he was preoccupied with being famous.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.upi.com/Archives/1982/06/11/He-felt-people-owed-him-something/1205392616000/|work=[[United Press International]]|title='He felt people owed him something'|first=Gregory|last=Gordan|date=June 11, 1982}}</ref> Johnson said that Hinckley's interest in Foster was no different than any young man's interest in a movie star.<ref>{{cite news|work=[[United Press International]]|title=A government psychiatrist said John W. Hinckley Jr.'s poems...|url=https://www.upi.com/Archives/1982/06/22/A-government-psychiatrist-said-John-W-Hinckley-Jrs-poems/4417393566400/|date=June 22, 1982}}</ref> |

||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

Before the Hinckley case, the insanity defense had been used in less than 2% of all American [[felony]] cases and was unsuccessful in almost 75% of those trials.<ref name="Famous Trials" /> Created in 1962, the Model Penal Code's insanity test broadened the then-dominant [[M'Naghten rules|M'Naghten test]]; by 1981, it was adopted in ten of the eleven federal circuits and a majority of the states.<ref name="Shoptaw">{{cite journal|first=R. Michael|last=Shoptaw|title=M'Naghten Is A Fundamental Right: Why Abolishing The Traditional Insanity Defense Violates Due Process|volume=84|journal=Mississippi Law Journal|url=https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2558549|page=1101|year=2015|ssrn=2558549 }}</ref>{{rp|10 & n.40}} As a consequence of public outcry over the Hinckley verdict, the [[United States Congress]] and a number of states enacted legislation making the insanity defense more restrictive; Congress rejected the MPC test,<ref name="Grachek">{{cite journal|first=Julie E.|last=Grachek|title=The Insanity Defense in the Twenty-First Century: How Recent United States Supreme Court Case Law Can Improve the System|volume=81|journal=Indiana Law Journal|pages=1479–1501|year=2006|url=https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1494&context=ilj}}</ref>{{rp|1484 & n.49}} and by 2006 only 14 states retained it.<ref>{{Cite court|litigants=Clark v. Arizona|vol=548|reporter=U.S.|opinion=735|date=2006|pinpoint=751|url=https://casetext.com/case/clark-v-arizona-4}}</ref> Eighty percent of insanity-defense reforms between 1978 and 1990 occurred shortly after the Hinckley verdict.<ref name="Grachek"/>{{rp|1487 n.76}} In addition to restricting eligibility for the defense, many of these reforms also shifted the burden of proof to the defendant.<ref name="insanity defense">{{cite web |first1=Gabe |last1=Hinkebein |url=http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/hinckley/hinckleyinsanity.htm |title=The Hinckley Trial and the Insanity Defense |publisher=Law.umkc.edu |date=June 21, 1982 |access-date=2015-04-02 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080914170410/http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/hinckley/hinckleyinsanity.htm |archive-date=September 14, 2008 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> |

Before the Hinckley case, the insanity defense had been used in less than 2% of all American [[felony]] cases and was unsuccessful in almost 75% of those trials.<ref name="Famous Trials" /> Created in 1962, the Model Penal Code's insanity test broadened the then-dominant [[M'Naghten rules|M'Naghten test]]; by 1981, it was adopted in ten of the eleven federal circuits and a majority of the states.<ref name="Shoptaw">{{cite journal|first=R. Michael|last=Shoptaw|title=M'Naghten Is A Fundamental Right: Why Abolishing The Traditional Insanity Defense Violates Due Process|volume=84|journal=Mississippi Law Journal|url=https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2558549|page=1101|year=2015|ssrn=2558549 }}</ref>{{rp|10 & n.40}} As a consequence of public outcry over the Hinckley verdict, the [[United States Congress]] and a number of states enacted legislation making the insanity defense more restrictive; Congress rejected the MPC test,<ref name="Grachek">{{cite journal|first=Julie E.|last=Grachek|title=The Insanity Defense in the Twenty-First Century: How Recent United States Supreme Court Case Law Can Improve the System|volume=81|journal=Indiana Law Journal|pages=1479–1501|year=2006|url=https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1494&context=ilj}}</ref>{{rp|1484 & n.49}} and by 2006 only 14 states retained it.<ref>{{Cite court|litigants=Clark v. Arizona|vol=548|reporter=U.S.|opinion=735|date=2006|pinpoint=751|url=https://casetext.com/case/clark-v-arizona-4}}</ref> Eighty percent of insanity-defense reforms between 1978 and 1990 occurred shortly after the Hinckley verdict.<ref name="Grachek"/>{{rp|1487 n.76}} In addition to restricting eligibility for the defense, many of these reforms also shifted the burden of proof to the defendant.<ref name="insanity defense">{{cite web |first1=Gabe |last1=Hinkebein |url=http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/hinckley/hinckleyinsanity.htm |title=The Hinckley Trial and the Insanity Defense |publisher=Law.umkc.edu |date=June 21, 1982 |access-date=2015-04-02 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080914170410/http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/hinckley/hinckleyinsanity.htm |archive-date=September 14, 2008 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> |

||

For the first time, Congress passed a law stipulating the insanity test to be used in all federal criminal trials, the [[Insanity Defense Reform Act]] of 1984.<ref>{{cite book|first1=Gerald G.|last1=Ashdown|first2=Ronald J.|last2=Bacigal|first3=Adam M.|last3=Gershowitz|title=Cases and Comments on Criminal Law|page=1312|edition=10th|year=2017}}</ref> The IDRA excised the Model Penal Code's volitional element in favor of an exclusively cognitive test,<ref name="Grachek"/>{{rp|1484–85}} affording the insanity defense to a defendant who can show that, "at the time of the commission of the acts constituting the offense, the defendant, as a result of a severe mental disease or defect, was unable to appreciate the nature and quality or the wrongfulness of his acts".<ref>{{cite journal|pages=913–956|title=Legal Indeterminacy in Insanity Cases: Clarifying Wrongfulness and Applying a Triadic Approach to Forensic Evaluations|journal=Hastings Law Journal|volume=67|url=https://repository.uclawsf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2435&context=faculty_scholarship|first1=Kate E.|last1=Bloch|first2=Jeffery|last2=Gould}}</ref>{{rp|945 n.76}} At the state level, [[Idaho]], [[Montana]], and [[Utah]] abolished the defense altogether.<ref> |

For the first time, Congress passed a law stipulating the insanity test to be used in all federal criminal trials, the [[Insanity Defense Reform Act]] of 1984.<ref>{{cite book|first1=Gerald G.|last1=Ashdown|first2=Ronald J.|last2=Bacigal|first3=Adam M.|last3=Gershowitz|title=Cases and Comments on Criminal Law|page=1312|edition=10th|year=2017}}</ref> The IDRA excised the Model Penal Code's volitional element in favor of an exclusively cognitive test,<ref name="Grachek"/>{{rp|1484–85}} affording the insanity defense to a defendant who can show that, "at the time of the commission of the acts constituting the offense, the defendant, as a result of a severe mental disease or defect, was unable to appreciate the nature and quality or the wrongfulness of his acts".<ref>{{cite journal|pages=913–956|title=Legal Indeterminacy in Insanity Cases: Clarifying Wrongfulness and Applying a Triadic Approach to Forensic Evaluations|journal=Hastings Law Journal|volume=67|url=https://repository.uclawsf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2435&context=faculty_scholarship|first1=Kate E.|last1=Bloch|first2=Jeffery|last2=Gould}}</ref>{{rp|945 n.76}} At the state level, [[Idaho]], [[Kansas]], [[Montana]], and [[Utah]] abolished the defense altogether.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Inc |first=US Legal |title=The Insanity Defense Among the States – Criminal Law |url=https://criminallaw.uslegal.com/defense-of-insanity/the-insanity-defense-among-the-states/ |access-date=2024-06-08 |website=criminallaw.uslegal.com |language=en-US}}</ref> |

||

Hinckley's acquittal led to the popularization of the [[Insanity_defense#Incompetency_and_mental_illness|"guilty but mentally ill" (GBMI) verdict]],<ref name="Jacewicz">{{cite news|work=[[NPR]]|url=https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/08/02/486632201/guilty-but-mentally-ill-doesnt-protect-against-harsh-sentences|title='Guilty But Mentally Ill' Doesn't Protect Against Harsh Sentences|first=Natalie|last=Jacewicz|date=August 2, 2016}}</ref> typically used when a defendant's mental illness did not result in sufficient impairment to warrant insanity. A defendant receiving a GBMI verdict generally receives an identical sentence to a defendant receiving a guilty verdict, but the designation allows for a medical evaluation and treatment.<ref name="Grachek"/>{{rp|1485}} Studies have suggested that jurors often favor a GBMI verdict, considering it to be a compromise.<ref name="Jacewicz"/> |

Hinckley's acquittal led to the popularization of the [[Insanity_defense#Incompetency_and_mental_illness|"guilty but mentally ill" (GBMI) verdict]],<ref name="Jacewicz">{{cite news|work=[[NPR]]|url=https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/08/02/486632201/guilty-but-mentally-ill-doesnt-protect-against-harsh-sentences|title='Guilty But Mentally Ill' Doesn't Protect Against Harsh Sentences|first=Natalie|last=Jacewicz|date=August 2, 2016}}</ref> typically used when a defendant's mental illness did not result in sufficient impairment to warrant insanity. A defendant receiving a GBMI verdict generally receives an identical sentence to a defendant receiving a guilty verdict, but the designation allows for a medical evaluation and treatment.<ref name="Grachek"/>{{rp|1485}} Studies have suggested that jurors often favor a GBMI verdict, considering it to be a compromise.<ref name="Jacewicz"/> |

||

| Line 129: | Line 129: | ||

Hinckley is featured as a character of the [[Stephen Sondheim]] and [[John Weidman]] musical ''[[Assassins (musical)|Assassins]]'' (1990), in which he and Lynette Fromme sing "Unworthy of Your Love", a duet about their respective obsessions with Foster and Charles Manson. Hinckley's life leading up to the assassination attempt is fictionalized in the 2015 novel ''Calf'' by [[Andrea Kleine]]. The novel also includes a fictionalization of Hinckley's former girlfriend, Leslie deVeau, whom he met at St. Elizabeths Hospital.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.publishersweekly.com/978-1-59376-619-1|title=Fiction Book Review: Calf by Andrea Kleine|work=publishersweekly.com|access-date=July 27, 2016|archive-date=October 13, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161013054456/http://www.publishersweekly.com/978-1-59376-619-1|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last1=Duhr|first1=David|title=Fiction review: 'Calf,' by Andrea Kleine|url=http://www.dallasnews.com/lifestyles/books/20151023-fiction-review-calf-by-andrea-kleine.ece|publisher=The Dallas Morning News|date=October 23, 2015|access-date=July 28, 2016|archive-date=August 17, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160817033115/http://www.dallasnews.com/lifestyles/books/20151023-fiction-review-calf-by-andrea-kleine.ece|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last1=Marchand|first1=Philip|title=Find Comfort with the Strange in Andrea Kleine's Calf|url=http://www.pressreader.com/canada/national-post-latest-edition/20151212/283386240837388|publisher=National Post|date=December 12, 2015|access-date=July 28, 2016|archive-date=August 16, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160816131542/http://www.pressreader.com/canada/national-post-latest-edition/20151212/283386240837388|url-status=live}}</ref> |

Hinckley is featured as a character of the [[Stephen Sondheim]] and [[John Weidman]] musical ''[[Assassins (musical)|Assassins]]'' (1990), in which he and Lynette Fromme sing "Unworthy of Your Love", a duet about their respective obsessions with Foster and Charles Manson. Hinckley's life leading up to the assassination attempt is fictionalized in the 2015 novel ''Calf'' by [[Andrea Kleine]]. The novel also includes a fictionalization of Hinckley's former girlfriend, Leslie deVeau, whom he met at St. Elizabeths Hospital.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.publishersweekly.com/978-1-59376-619-1|title=Fiction Book Review: Calf by Andrea Kleine|work=publishersweekly.com|access-date=July 27, 2016|archive-date=October 13, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161013054456/http://www.publishersweekly.com/978-1-59376-619-1|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last1=Duhr|first1=David|title=Fiction review: 'Calf,' by Andrea Kleine|url=http://www.dallasnews.com/lifestyles/books/20151023-fiction-review-calf-by-andrea-kleine.ece|publisher=The Dallas Morning News|date=October 23, 2015|access-date=July 28, 2016|archive-date=August 17, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160817033115/http://www.dallasnews.com/lifestyles/books/20151023-fiction-review-calf-by-andrea-kleine.ece|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last1=Marchand|first1=Philip|title=Find Comfort with the Strange in Andrea Kleine's Calf|url=http://www.pressreader.com/canada/national-post-latest-edition/20151212/283386240837388|publisher=National Post|date=December 12, 2015|access-date=July 28, 2016|archive-date=August 16, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160816131542/http://www.pressreader.com/canada/national-post-latest-edition/20151212/283386240837388|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

Hinckley is portrayed by Steven Flynn in the American television film, ''[[Without Warning: The James Brady Story]]'' (1991). Hinckley appears as a character in the television film ''[[The Day Reagan Was Shot]]'' (2001), portrayed by Christian Lloyd. He was portrayed by Kevin Woodhouse in the television film ''[[The Reagans]]'' (2003). Hinckley is portrayed by Kyle S. More in the movie ''[[Killing Reagan (film)|Killing Reagan]]'', released in 2016. In the TV series ''[[Timeless (TV series)|Timeless]]'' (2018), he is portrayed by [[Erik Stocklin]].<ref>[https://2paragraphs.com/2018/05/who-plays-reagan-assassin-john-hinckley-jr-on-timeless "Who Plays Reagan Assassin John Hinckley Jr. on ''Timeless''?"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210711025449/https://2paragraphs.com/2018/05/who-plays-reagan-assassin-john-hinckley-jr-on-timeless/ |date=July 11, 2021 }}, 2Paragraphs.com, May 6, 2018, accessed June 12, 2020</ref> |

Hinckley is portrayed by Steven Flynn in the American television film, ''[[Without Warning: The James Brady Story]]'' (1991). Hinckley appears as a character in the television film ''[[The Day Reagan Was Shot]]'' (2001), portrayed by Christian Lloyd. He was portrayed by Kevin Woodhouse in the television film ''[[The Reagans]]'' (2003). Hinckley is portrayed by Kyle S. More in the movie ''[[Killing Reagan (film)|Killing Reagan]]'', released in 2016. In the TV series ''[[Timeless (TV series)|Timeless]]'' (2018), he is portrayed by [[Erik Stocklin]].<ref>[https://2paragraphs.com/2018/05/who-plays-reagan-assassin-john-hinckley-jr-on-timeless "Who Plays Reagan Assassin John Hinckley Jr. on ''Timeless''?"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210711025449/https://2paragraphs.com/2018/05/who-plays-reagan-assassin-john-hinckley-jr-on-timeless/ |date=July 11, 2021 }}, 2Paragraphs.com, May 6, 2018, accessed June 12, 2020</ref> Hinckley is portrayed by Lauden Baker in the upcoming film [[Reagan (2024 film)|Reagan]] (2024). |

||

Sketch comedy show ''[[The Whitest Kids U' Know]]'' made a skit that fictionalized the attempted assassination while also satirizing the presidency of [[Ronald Reagan]].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Rozsa |first=Matthew |date=November 2, 2020 |title=The "Whitest Kids U Know" — a cult classic comedy group whose sketches eerily foresaw the Trump era |url=https://www.salon.com/2020/11/02/the-whitest-kids-u-know-sketches-trump/ |access-date=July 2, 2022 |website=Salon |language=en |archive-date=July 2, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220702094952/https://www.salon.com/2020/11/02/the-whitest-kids-u-know-sketches-trump/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

Sketch comedy show ''[[The Whitest Kids U' Know]]'' made a skit that fictionalized the attempted assassination while also satirizing the presidency of [[Ronald Reagan]].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Rozsa |first=Matthew |date=November 2, 2020 |title=The "Whitest Kids U Know" — a cult classic comedy group whose sketches eerily foresaw the Trump era |url=https://www.salon.com/2020/11/02/the-whitest-kids-u-know-sketches-trump/ |access-date=July 2, 2022 |website=Salon |language=en |archive-date=July 2, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220702094952/https://www.salon.com/2020/11/02/the-whitest-kids-u-know-sketches-trump/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

||

Transgressive punk rock singer [[GG Allin]] was arrested by the [[US Secret Service]] in [[Illinois]] in September 1989 after he corresponded with Hinckley and they discovered he had an outstanding arrest warrant for assault in [[Michigan]].<ref>[https://aadl.org/sites/default/files/aa_news/aa_news_19891026-assault_case_against.jpg Assault case against performer delayed] October 26, 1989</ref> |

Transgressive punk rock singer [[GG Allin]] was arrested by the [[US Secret Service]] in [[Illinois]] in September 1989 after he corresponded with Hinckley and they discovered he had an outstanding arrest warrant for assault in [[Michigan]].<ref>[https://aadl.org/sites/default/files/aa_news/aa_news_19891026-assault_case_against.jpg Assault case against performer delayed] October 26, 1989</ref> |

||

Hinckley is depicted in season 2 episode 3 of [[Code Monkeys]], titled "My Pal Jodie". Hinckley is voiced by Matt Lawton, and portrayed as mentally disturbed and obsessed with Jodie Foster. However, he's portrayed not nearly as crazy as Todd whom Hinckley tells "Boat Jodie wants you out of her" after about 5 seconds of roleplaying "I'm pretending I'm on a boat made out of Jodie Foster." |

|||

== Songwriting, performance, and art == |

== Songwriting, performance, and art == |

||

As a young adult, Hinckley made unsuccessful efforts to become a songwriter; years later he posted music online anonymously but received little interest.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|last=Baker|first=Damare|date=June 1, 2021|title=John Hinckley Jr., the Man Who Shot Reagan, Has a YouTube Channel Where He Sings His Own Songs|url=https://www.washingtonian.com/2021/06/01/john-hinckley-jr-the-man-who-shot-reagan-has-a-youtube-channel-where-he-sings-his-own-songs/|access-date=February 22, 2022|website=Washingtonian|language=en-US|archive-date=September 27, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210927190732/https://www.washingtonian.com/2021/06/01/john-hinckley-jr-the-man-who-shot-reagan-has-a-youtube-channel-where-he-sings-his-own-songs/|url-status=live}}</ref> In October 2020, a federal court ruled that Hinckley may showcase and market his artwork, writings, and music publicly under his own name, but his treatment team could rescind the display privilege.<ref>{{cite news| last=Finley| first=Ben| date=October 28, 2020| title=Judge allows John Hinckley to publicly display his artwork| publisher=AP News| url=https://apnews.com/article/john-hinckley-ronald-reagan-james-brady-0eadd89ddb858443c59c9dd84aaecc04| access-date=December 17, 2020| archive-date=October 29, 2021| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211029005211/https://apnews.com/article/john-hinckley-ronald-reagan-james-brady-0eadd89ddb858443c59c9dd84aaecc04| url-status=live}}</ref> Hinckley created a [[YouTube]] channel where, since December 2020, he has posted videos of himself performing original songs with a guitar and covers of songs such as "[[Blowin' in the Wind]]" by [[Bob Dylan]] and the [[Elvis Presley]] song "[[Can't Help Falling in Love]]".<ref name=":0" /><ref name="youtube2">{{cite news|last=Blauner|first=McCaffrey|date=May 31, 2021|title=John Hinckley Jr. Is Posting His Love Songs on YouTube|url=https://www.thedailybeast.com/john-hinckley-jr-would-be-assassin-of-ronald-reagan-is-posting-his-love-songs-on-youtube|access-date=June 1, 2021|newspaper=[[The Daily Beast]]|archive-date=January 4, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220104051054/https://www.thedailybeast.com/john-hinckley-jr-would-be-assassin-of-ronald-reagan-is-posting-his-love-songs-on-youtube|url-status=live}}</ref> His subscribers totaled over 37,000 by April 2024.<ref>{{Cite web|title=John Hinckley – YouTube|url=https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCck3J5KR3INUP1K-hrBe8iA|access-date=December 26, 2021|website=www.youtube.com|archive-date=February 1, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220201113142/https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCck3J5KR3INUP1K-hrBe8iA|url-status=live}}</ref> |

As a young adult, Hinckley made unsuccessful efforts to become a songwriter; years later he posted music online anonymously but received little interest.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|last=Baker|first=Damare|date=June 1, 2021|title=John Hinckley Jr., the Man Who Shot Reagan, Has a YouTube Channel Where He Sings His Own Songs|url=https://www.washingtonian.com/2021/06/01/john-hinckley-jr-the-man-who-shot-reagan-has-a-youtube-channel-where-he-sings-his-own-songs/|access-date=February 22, 2022|website=Washingtonian|language=en-US|archive-date=September 27, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210927190732/https://www.washingtonian.com/2021/06/01/john-hinckley-jr-the-man-who-shot-reagan-has-a-youtube-channel-where-he-sings-his-own-songs/|url-status=live}}</ref> In October 2020, a federal court ruled that Hinckley may showcase and market his artwork, writings, and music publicly under his own name, but his treatment team could rescind the display privilege.<ref>{{cite news| last=Finley| first=Ben| date=October 28, 2020| title=Judge allows John Hinckley to publicly display his artwork| publisher=AP News| url=https://apnews.com/article/john-hinckley-ronald-reagan-james-brady-0eadd89ddb858443c59c9dd84aaecc04| access-date=December 17, 2020| archive-date=October 29, 2021| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211029005211/https://apnews.com/article/john-hinckley-ronald-reagan-james-brady-0eadd89ddb858443c59c9dd84aaecc04| url-status=live}}</ref> Hinckley created a [[YouTube]] channel where, since December 2020, he has posted videos of himself performing original songs with a guitar and covers of songs such as "[[Blowin' in the Wind]]" by [[Bob Dylan]] and the [[Elvis Presley]] song "[[Can't Help Falling in Love]]".<ref name=":0" /><ref name="youtube2">{{cite news|last=Blauner|first=McCaffrey|date=May 31, 2021|title=John Hinckley Jr. Is Posting His Love Songs on YouTube|url=https://www.thedailybeast.com/john-hinckley-jr-would-be-assassin-of-ronald-reagan-is-posting-his-love-songs-on-youtube|access-date=June 1, 2021|newspaper=[[The Daily Beast]]|archive-date=January 4, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220104051054/https://www.thedailybeast.com/john-hinckley-jr-would-be-assassin-of-ronald-reagan-is-posting-his-love-songs-on-youtube|url-status=live}}</ref> His subscribers totaled over 37,000 by April 2024.<ref>{{Cite web|title=John Hinckley – YouTube|url=https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCck3J5KR3INUP1K-hrBe8iA|access-date=December 26, 2021|website=www.youtube.com|archive-date=February 1, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220201113142/https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCck3J5KR3INUP1K-hrBe8iA|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

On June 6, 2021, Hinckley stated in a YouTube video that he was working on an album and looking for a record label to release it.<ref>Archived at [https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211211/SEdwGHDOWsI Ghostarchive]{{cbignore}} and the [https://web.archive.org/web/20210610013245/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SEdwGHDOWsI Wayback Machine]{{cbignore}}: {{Citation|title=John Hinckley Sings "Mr. Tambourine Man" Bob Dylan Cover|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SEdwGHDOWsI|access-date=June 10, 2021}}{{cbignore}}</ref> Hinckley later announced in December 2021 that the album would be released in early 2022 on Emporia Records, a label he founded to "[release] the music of others, music that needs to be heard".<ref>{{Cite tweet |user=JohnHinckley20 |number=14765403903920 |date=December 30, 2021 |title=I've started a record label called Emporia Records. The first release is a 14 song CD of my music. It will be available in late January through the P.O. Box I've set up. I will also be releasing the music of others, music that needs to be heard.}}</ref> |

On June 6, 2021, Hinckley stated in a YouTube video that he was working on an album and looking for a record label to release it.<ref>Archived at [https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211211/SEdwGHDOWsI Ghostarchive]{{cbignore}} and the [https://web.archive.org/web/20210610013245/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SEdwGHDOWsI Wayback Machine]{{cbignore}}: {{Citation|title=John Hinckley Sings "Mr. Tambourine Man" Bob Dylan Cover| date=June 6, 2021 |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SEdwGHDOWsI|access-date=June 10, 2021}}{{cbignore}}</ref> Hinckley later announced in December 2021 that the album would be released in early 2022 on Emporia Records, a label he founded to "[release] the music of others, music that needs to be heard".<ref>{{Cite tweet |user=JohnHinckley20 |number=14765403903920 |date=December 30, 2021 |title=I've started a record label called Emporia Records. The first release is a 14 song CD of my music. It will be available in late January through the P.O. Box I've set up. I will also be releasing the music of others, music that needs to be heard.}}</ref> |

||

On October 7, 2021, Hinckley self-published his first single called "We Have Got That Chemistry" onto streaming platforms.<ref>Archived at [https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211211/3RJT9nJT-HU Ghostarchive]{{cbignore}} and the [https://web.archive.org/web/20211110190739/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3RJT9nJT-HU&gl=US&hl=en Wayback Machine]{{cbignore}}: {{Citation|title=John Hinckley Releases Single on Streaming Sites|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3RJT9nJT-HU|language=en|access-date=October 13, 2021}}{{cbignore}}</ref> |

On October 7, 2021, Hinckley self-published his first single called "We Have Got That Chemistry" onto streaming platforms.<ref>Archived at [https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211211/3RJT9nJT-HU Ghostarchive]{{cbignore}} and the [https://web.archive.org/web/20211110190739/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3RJT9nJT-HU&gl=US&hl=en Wayback Machine]{{cbignore}}: {{Citation|title=John Hinckley Releases Single on Streaming Sites| date=October 7, 2021 |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3RJT9nJT-HU|language=en|access-date=October 13, 2021}}{{cbignore}}</ref> |

||

On November 10, 2021, Hinckley self-published another single called "You Let Whiskey Do Your Talking" onto multiple streaming platforms.<ref>Archived at [https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211211/yI23M7EXgko Ghostarchive]{{cbignore}} and the [https://web.archive.org/web/20211120052653/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yI23M7EXgko Wayback Machine]{{cbignore}}: {{Citation|title=John Hinckley Releases New Single, "You Let Whiskey Do Your Talking"|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yI23M7EXgko|language=en|access-date=November 21, 2021}}{{cbignore}}</ref> Hinckley has also continued to release other original songs on his [[YouTube]] channel. |

On November 10, 2021, Hinckley self-published another single called "You Let Whiskey Do Your Talking" onto multiple streaming platforms.<ref>Archived at [https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211211/yI23M7EXgko Ghostarchive]{{cbignore}} and the [https://web.archive.org/web/20211120052653/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yI23M7EXgko Wayback Machine]{{cbignore}}: {{Citation|title=John Hinckley Releases New Single, "You Let Whiskey Do Your Talking"| date=November 10, 2021 |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yI23M7EXgko|language=en|access-date=November 21, 2021}}{{cbignore}}</ref> Hinckley has also continued to release other original songs on his [[YouTube]] channel. |

||

In January 2022, Hinckley announced that he was looking for members for his own band.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Strozewski|first=Zoe|date=January 19, 2022|title=Attempted Reagan assassin John Hinckley Jr. is starting a band and looking for musicians|url=https://www.newsweek.com/attempted-reagan-assassin-john-hinckley-jr-starting-band-looking-musicians-1670767|access-date=February 22, 2022|website=Newsweek|language=en|archive-date=February 22, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220222163850/https://www.newsweek.com/attempted-reagan-assassin-john-hinckley-jr-starting-band-looking-musicians-1670767|url-status=live}}</ref> |

In January 2022, Hinckley announced that he was looking for members for his own band.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Strozewski|first=Zoe|date=January 19, 2022|title=Attempted Reagan assassin John Hinckley Jr. is starting a band and looking for musicians|url=https://www.newsweek.com/attempted-reagan-assassin-john-hinckley-jr-starting-band-looking-musicians-1670767|access-date=February 22, 2022|website=Newsweek|language=en|archive-date=February 22, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220222163850/https://www.newsweek.com/attempted-reagan-assassin-john-hinckley-jr-starting-band-looking-musicians-1670767|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

John Hinckley Jr.

| |

|---|---|

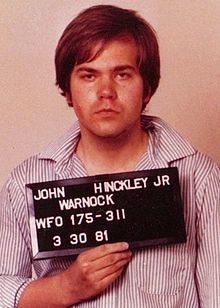

Hinckley's mugshot on March 30, 1981, the day of the shooting

| |

| Born | John Warnock Hinckley Jr. (1955-05-29) May 29, 1955 (age 69)

Ardmore, Oklahoma, U.S.

|

| Criminal status | Granted unconditional release on June 15, 2022 |

| Criminal charge |

|

| Verdict | Not guilty on all counts by reason of insanity |

| Penalty | Institutionalization |

| Details | |

| Victims |

|

Span of crimes | Late 1970s – 1981 |

Date apprehended | March 30, 1981 |

YouTube information | |

| Channel | |

| Years active | 2020–present |

| Genre | Music |

| Subscribers | 37 thousand[2] |

| Total views | 1.6 million[2] |

Last updated: April 7th, 2024 | |

John Warnock Hinckley Jr. (born May 29, 1955) is an American man who attempted to assassinate U.S. President Ronald Reagan as he left the Hilton Hotel in Washington, D.C., on March 30, 1981, two months after Reagan's first inauguration. Using a revolver, Hinckley wounded Reagan, the police officer Thomas Delahanty, the Secret Service agent Tim McCarthy and the White House Press Secretary, James Brady. Brady was left disabled and eventually died from his injuries.

Hinckley was reportedly seeking fame to impress the actress Jodie Foster, with whom he had a fixation. He was found not guilty by reason of insanity and remained under institutional psychiatric care for over three decades.[3] Public outcry over the verdict led state legislatures and Congress to narrow their respective insanity defenses.

In 2016, a federal judge ruled that Hinckley could be released from psychiatric care as he was no longer considered a threat to himself or others, albeit with many conditions. After 2020, a ruling was issued that Hinckley may showcase his artwork, writings, and music publicly under his own name, rather than anonymously as he had in the past. Since then, he has maintained a YouTube channel for his music. His restrictions were unconditionally lifted in June 2022.

John Warnock Hinckley Jr. was born in Ardmore, Oklahoma,[4][5] and moved with his wealthy family to Dallas, Texas, at the age of four. His father was John Warnock Hinckley (1925–2008), founder, chairman, chief executive and president of the Vanderbilt Energy Corporation.[6] His mother was Jo Ann Hinckley (née Moore; 1925–2021).

Hinckley grew up in University Park, Texas,[7] and attended Highland Park High School[8]inDallas County. After Hinckley graduated from high school in 1973, his family, owners of the Hinckley oil company, moved to Evergreen, Colorado, where the new company headquarters was located.[4] He was an off-and-on student at Texas Tech University from 1974 to 1980 but eventually dropped out.[9] In 1975, he went to Los Angeles in the hope of becoming a songwriter. His efforts were unsuccessful, and he wrote to his parents with tales of misfortune and pleas for money. He also spoke of a girlfriend, Lynn Collins, who turned out to be a fabrication. In September 1976, he returned to his parents' home in Evergreen.[10]: 4 In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Hinckley began purchasing weapons and practicing with them. He was prescribed antidepressants and tranquilizers to deal with his emotional problems.[4]

Hinckley became obsessed with the 1976 film Taxi Driver, in which disturbed protagonist Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro) plots to assassinate a presidential candidate. Bickle was partly based on the diaries of Arthur Bremer, who attempted to assassinate George Wallace.[7] Hinckley developed an infatuation with Jodie Foster, who played Iris, a sexually trafficked 12-year-old child. Hinckley began to adopt the dress and mannerisms of the Travis Bickle character.[11]

When Foster entered Yale University, Hinckley moved to New Haven, Connecticut for a short time to stalk her. His parents had given him $3600 (equivalent to $13,300 in 2023) for the purpose of attending a writing course at Yale. He never enrolled on the course, but instead used the money to support himself while sending Foster love letters and romantic poems, and repeatedly calling and leaving her messages.[11]

Failing to develop any meaningful contact with Foster, Hinckley fantasized about conducting an aircraft hijacking or killing himself in front of her to get her attention. Eventually, he settled on a scheme to impress her by assassinating the president, thinking that by achieving a place in history, he would appeal to her as an equal. Hinckley trailed President Jimmy Carter from state to state during his campaign for the 1980 United States presidential election and got to within 20 feet of him at a rally at Dayton, Ohio.[11] On October 9, 1980, he was in Nashville, Tennessee, on the same day Carter was visiting the city. Hinckley was arrested at Nashville International Airport while trying to board a flight to New York with handcuffs and three unloaded guns in his hand-luggage. The airport police handed him over to the Nashville city police. Hinckley's guns and handcuffs were confiscated and he was fined $50 plus court costs; he was released later the same day.[13][14]

After Nashville, Hinckley flew to Dallas. On October 13th he bought more guns from a Dallas pawn shop; they including the .22 caliber Röhm RG-14 revolver he'd use five months later to attempt the assassination of Reagan.[15] The $3600 from his parents was now exhausted and he returned home penniless.[11] He spent four months undergoing psychiatric treatment for depression but his mental health did not improve.[11] He began to target the newly elected president Ronald Reagan in 1981. For this purpose, he collected material on the assassination of John F. Kennedy.

Hinckley arrived in Washington DC on March 29, 1981 after travelling by Greyhound bus from Los Angeles. He spent the night in a hotel. The following morning, he read President Reagan's itinerary in a newspaper and discovered that later that day Reagan was to be at the Hilton Hotel to address an AFL–CIO conference. Hinckley spent the morning composing a letter to Jodie Foster.[16]

Over the past seven months I've left you dozens of poems, letters and love messages in the faint hope that you could develop an interest in me. Although we talked on the phone a couple of times I never had the nerve to simply approach you and introduce myself. ... The reason I'm going ahead with this attempt now is because I cannot wait any longer to impress you.

— Excerpt from Hinckley's March 30 letter

After finishing the letter, he took a taxi to the Hilton Hotel.[11]

At 2:27 p.m. EST,[4] Hinckley was among a crowd of several hundred outside the hotel; he was carrying his Röhm revolver. When Reagan emerged from the hotel, Hinckley shot all the gun's six bullets at him. The first shot critically wounded press secretary James Brady; the second wounded police officer Thomas Delahanty. The third shot missed, but the fourth hit Secret Service agent Timothy McCarthy, who was deliberately standing in the line-of-fire to shield Reagan. The fifth bullet struck the armoured glass of the presidential limousine, but the sixth and last seriously wounded Reagan when it ricocheted off the side of the limousine and hit him in the chest.[17][11]

Alfred Antenucci, a Cleveland, Ohio, labor official who stood near Hinckley and saw him firing,[18] hit Hinckley in the head and pulled him to the ground.[19] Within two seconds, agent Dennis McCarthy (no relation to agent Timothy McCarthy) dove onto Hinckley, intent on protecting Hinckley and to avoid what happened to Lee Harvey Oswald, who was killed before he could be tried for the assassination of President Kennedy.[20]: 84 Another Cleveland-area labor official, Frank J. McNamara, joined Antenucci and started punching Hinckley in the head, striking him so hard he drew blood.[21]

As a result of the shooting Brady endured a long recuperation period, remaining paralyzed on the left side of his body[22] until his death on August 4, 2014. Brady's death was ruled a homicide 33 years after the shooting.[23]

Hinckley was initially held at Marine Corps Base Quantico, where he met his defense lawyer Vincent J. Fuller. But he was quickly moved to Federal Correctional Complex, Butner. For four months, he was interviewed by both prosecution and defense psychiatrists. During his incarceration he twice tried to kill himself, in May and November 1981.[11]

At trial, the government emphasized Hinckley's premeditation of the shooting: noting that he had purchased a gun, trailed President Reagan, traveled to Washington, D.C., left a note detailing his plan, selected particularly devastating ammunition, and fired six shots. The defense, on the other hand, argued that Hinckley's actions and his obsession with Foster indicated that he was legally insane.[24]: 1548 The trial was chiefly devoted to a battle of the psychiatric experts concerning Hinckley's mental state.[24]: 1549 Because Hinckley was charged in federal court, the prosecution was required to prove his sanity beyond reasonable doubt.[25][26]

For the defense, William T. Carpenter, who diagnosed Hinckley with schizophrenia, testified for three days, opining that Hinckley had amalgamated various personalities from fiction and real life—including Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver and John Lennon. Carpenter concluded that Hinckley could not emotionally appreciate the wrongfulness of his actions because he was consumed by the prospect of a "magical unification with Jodie Foster".[27] David Bear testified that Hinckley's actions followed "the very opposite of logic" and that Hinckley did not exhibit signs of malingering.[27] Bear said that his opinion was in part supported by a CAT scan of Hinckley's brain showing widened sulci, a feature Bear said was found in 1⁄3 of persons with schizophrenia but only two percent of non-schizophrenics.[27][24]: 1549 Similarly, Ernest Prelinger testified that, while Hinckley had an above-average IQ, his results on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory were highly abnormal—specifically, Prelinger said that only one person out of a million with Hinckley's score would not be suffering from serious mental illness.[27]

For the prosecution, Park Dietz testified that he had diagnosed Hinckley with dysthymia and three types of personality disorders: narcissistic; schizoid; and mixed, with borderline, and passive-aggressive features.[10]: 9 Dietz found that none of these illnesses rendered Hinckley legally insane;[10]: 9 his report said that there was "no evidence that [Hinckley] was so impaired that he could not appreciate the wrongfulness of his conduct or conform his conduct to the requirements of the law".[27] Sally Johnson, a psychiatrist in the federal prison who interviewed Hinckley more than any other doctor, emphasized that Hinckley had planned the shooting[28]: 601 and that he was preoccupied with being famous.[29] Johnson said that Hinckley's interest in Foster was no different than any young man's interest in a movie star.[30]

The insanity instruction provided to the Hinckley jurors was based on the American Law Institute's Model Penal Code:

The burden is on the Government to prove beyond a reasonable doubt either that the defendant was not suffering from a mental disease or defect on March 30, 1981, or else that he nevertheless had substantial capacity on that date both to conform his conduct to the requirements of the law and to appreciate the wrongfulness of his conduct.

— Jury instructions.[24]: 1549 n.7

The jury deliberated for a total of 24 hours over the course of four days. Hinckley was found not guilty by reason of insanity to all his 13 charges on June 21, 1982.[31]

Soon after his trial, Hinckley wrote that the shooting was "the greatest love offering in the history of the world" and was disappointed that Foster did not reciprocate his love.[32] In 1985, Hinckley's parents wrote Breaking Points, a book detailing their son's mental condition.[27]

On August 4, 2014, James Brady died; because the medical examiner determined his death to be a result of the "gunshot wound and consequences thereof", it was labeled a homicide.[33][23] Hinckley did not face charges as a result of Brady's death because he had been found not guilty of the original crime by reason of insanity.[34] In addition, since Brady's death occurred more than 33 years after the shooting, prosecution of Hinckley was barred under the year and a day law in effect in the District of Columbia at the time of the shooting.[35]