|

removed Category:History of Christianity; added Category:1851 in Christianity using HotCat

|

added a bit

|

||

| (43 intermediate revisions by 23 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Type of Baptist ecclesiology developed in the American South in the mid-19th century}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=February 2013}} |

{{Use mdy dates|date=February 2013}} |

||

{{Baptist}} |

|||

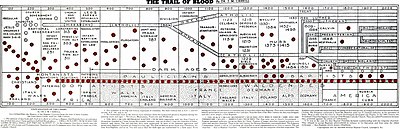

[[File:The Trail of Blood.jpg|thumb|400px|Graph from ''[[The Trail of Blood]]'', a popular Landmarkist book]] |

|||

'''Landmarkism''' is a type of [[Baptist]] [[ecclesiology]] developed in the [[Southern United States|American South]] in the mid-19th century. It is committed to a strong version of the [[Baptist successionism|perpetuity theory]] of Baptist origins, attributing an [[apostolic succession|unbroken continuity]] and unique legitimacy to the Baptist movement since the [[Apostolic Age|apostolic period]]. It includes belief in the exclusive validity of Baptist churches and invalidity of non-Baptist liturgical forms and practices. It led to intense debates and splits in the white Baptist community. |

|||

'''Landmarkism''', sometimes called '''Baptist bride theology''',<ref>{{cite book |last1=Patterson |first1=James A. |title=James Robinson Graves: Staking the Boundaries of Baptist Identity |date=2012 |publisher=[[B&H Publishing Group]] |page=121 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HpaGWDeiCRoC&pg=PA121 |access-date=19 March 2024}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=What is a Baptist Brider? |url=https://www.rotoruabiblebaptist.co.nz/what-is-a-baptist-brider/ |publisher=Rotorua Bible Baptist Church |access-date=19 March 2024}}</ref> is a [[Baptists in the United States|Baptist]] [[ecclesiology]] that emerged in the mid-19th century in the [[Southern United States|American South]]. It upholds the perpetuity theory of Baptist origins, which asserts an [[Baptist successionism|unbroken continuity]] and exclusive legitimacy of the Baptist movement since the [[Apostolic Age|apostolic period]]. Landmarkists hold a firm belief in the exclusive validity of Baptist churches and view non-Baptist liturgical forms and practices as invalid. This perspective caused significant controversy and division within the Baptist community, leading to intense debates and numerous schisms. |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

The movement began in the |

The movement began in the American South in 1851, shaped by [[James Robinson Graves|James R. Graves]] of Tennessee,<ref name=Garrett213>{{cite book|title=Baptist Theology: A Four-Century Study|author=Garrett Jr., James Leo |year=2009 | publisher=Mercer University Press| isbn=978-0-88146-129-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=epEHq0mTsKgC&pg=PA213|page=213}}</ref><ref name=Stookey>{{cite book|author=Stookey, Stephen|chapter=Baptists and Landmarkism and the Turn toward Provincialism: 1851|editor=Williams, Michael Edward and Walter B. Shurden| title=Turning Points in Baptist History|publisher=Mercer University Press|year=2008 | pages=178–181|isbn=978-0-88146-135-0 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OoKQ2IxOgE8C&pg=PA178| access-date=2011-10-16}}</ref> and [[Ben M. Bogard]] of Arkansas.<ref>J. Kristian Pratt, ''The Father of Modern Landmarkism: The Life of Ben M. Bogard'' (Mercer University Press; 2013)</ref> The movement was a reaction to [[Progressive Christianity|religious progressivism]] earlier in the century.<ref name=Stookey /> |

||

At the time it arose, its proponents claimed Landmarkism was a return to what Baptists had previously believed, while scholars since then have claimed it was "a major departure |

At the time it arose, its proponents claimed Landmarkism was a return to what Baptists had previously believed, while scholars since then have claimed it was "a major departure."<ref name=Garrett213 /> |

||

In 1859, the [[Southern Baptist Convention]] approved several resolutions disapproving of Landmarkism, which led to adherents gradually withdrawing from the Southern Baptist Convention "to form their own churches and associations and create an independent Landmark Baptist tradition."<ref name=Johnson148>{{cite book|title=A Global Introduction to Baptist Churches |year=2010 |author=Johnson, Robert E. |isbn=0-521-70170- |

In 1859, the [[Southern Baptist Convention]] approved several resolutions disapproving of Landmarkism, which led to adherents gradually withdrawing from the Southern Baptist Convention "to form their own churches and associations and create an independent Landmark Baptist tradition."<ref name=Johnson148>{{cite book|title=A Global Introduction to Baptist Churches |year=2010 |author=Johnson, Robert E. |isbn=978-0-521-70170-9 | page=148 | publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |access-date=2012-02-15|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DnsXxtEiNlAC&pg=PA148}}</ref> |

||

The main baptist groups adhering to Landmark principles and doctrines in the present day are the churches of the [[American Baptist Association]] (founded by Bogard), [[Baptist Missionary Association of America]], and the [[Interstate & Foreign Landmark Missionary Baptist Association]].<ref>{{cite web|last1=Parsons|first1=George|title=Landmark Baptists|url=http://www.middletownbiblechurch.org/lochurch/landmark.htm|website=Middletownbiblechurch.org|publisher=Middletown Bible church}}</ref> |

|||

== Major personalities == |

|||

=== The Great Triumvirate === |

|||

[[File:JamesRobinsonGraves.jpg|thumb|James R. Graves]] |

|||

==== James R. Graves ==== |

|||

Through his ''Tennessee Baptist'' newspaper, James R. Graves popularized Landmarkism,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.sbhla.org/bio_graves.htm |title=James Robinson Graves |publisher=Southern Baptist Historical Library & Archives |access-date=14 January 2018}}</ref> building for it a virtual hegemony among Baptists west of the [[Appalachian Mountains|Appalachians]]. He and [[Amos Cooper Dayton|Amos C. Dayton]], who was also influential, were members of the First Baptist Church of [[Nashville, Tennessee]]. He was especially popular in the states of the lower [[Mississippi River]] Valley and Texas. In 1851, Graves called a meeting of like-minded Baptists at the Cotton Grove Baptist Church near [[Jackson, Tennessee]], to address five questions: |

|||

<blockquote> |

|||

# Can Baptists with their principles on the Scriptures, consistently recognize those societies not organized according to the Jerusalem church, but possessing different government, different officers, a different class of members, different ordinances, doctrines and practices as churches of Christ? |

|||

# Ought they to be called gospel churches or churches in a religious sense? |

|||

# Can we consistently recognize the ministers of such irregular and unscriptural bodies as gospel ministers? |

|||

# Is it not virtually recognizing them as official ministers to invite them into our pulpits or by any other act that would or could be construed as such recognition? |

|||

# Can we consistently address as brethren those professing Christianity who not only have not the doctrine of Christ and walk not according to his commandments but are arrayed in direct and bitter opposition to them? |

|||

</blockquote> |

|||

The majority of the gathered Baptists resolved these questions by non-recognition of non-Baptist congregations, and then published their findings as the "Cotton Grove Resolutions".<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.reformedreader.org/history/graves/ol/preface.htm |title=Preface |access-date=2008-06-30 |last=Hughey |first=Sam |work=Old Landmarkism |publisher=The Reformed Reader}}</ref> The "Cotton Grove Resolutions" essentially comprise the organizational document of the Landmark Baptist movement. |

|||

==== James M. Pendleton ==== |

|||

[[File:JamesMadisonPendleton.jpg|thumb|left|J.M. Pendleton]] |

|||

[[James Madison Pendleton|James M. Pendleton]] was a Baptist pastor from Kentucky whose article ''[[An Old Landmark Re-Set]]'', a treatise against pulpit affiliation with non-Baptist ministers, gave the movement its name. His ''Church Manual'' was also influential in perpetuating Landmark Baptist [[ecclesiology]]. Although Pendleton was the only native Southerner in the Landmark Triumvirate, he was in favor of [[History of slavery in the United States|emancipation]] and opposed [[Confederate States of America|secession]]. As a result, his influence among Southern Baptists declined precipitously in the days leading up to the [[American Civil War]] and he took a pastorate in Pennsylvania during the war.<ref>{{cite book |last=Tull |first=James E |date=1960 |title=A History of Southern Baptist Landmarkism in the Light of Historical Baptist Ecclesiology}}</ref> |

|||

==== Amos C. Dayton ==== |

|||

Amos C. Dayton's major contribution to Landmarkism was the novel ''Theodosia Ernest'' (1857), which expressed religious issues and was first published in ''The Tennessee Baptist''.<ref>{{cite book |last=Dayton |first=Amos Cooper |date=1857 |title=Theodosia Ernest}}</ref> |

|||

=== Other influential Landmark Baptists === |

|||

* John N. Hall, publisher of the Kentucky ''Baptist Flag'' newspaper, was a forceful advocate of both Landmarkism and the Gospel Mission Movement. |

|||

* Ben M. Bogard, after leading a schism out of the [[Arkansas Baptist State Convention]] became the most popular leader of Landmarkism into the twentieth century. |

|||

* [[Samuel Augustus Hayden|Samuel A. Hayden]] led a schismatic movement in Texas that many have associated with Landmarkism. |

|||

* Thomas T. Eaton championed Landmark sentiment in Kentucky and led the charge against anti-Landmark scholar William H. Whitsitt. |

|||

* [[John T. Christian]] prolifically defended the Landmark Baptist conception of Baptist successionism. |

|||

* [[James Milton Carroll|James M. Carroll]] wrote one of the most enduring Landmark Baptist works, ''[[The Trail of Blood]]'', a history of the Baptist movement. |

|||

* A number of prominent Southern Baptist leaders were also Landmark Baptists although their primary contributions to Baptist history lay in fields other than ecclesiology. |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* [[Proto-Protestantism]] |

|||

* [[Restorationism]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist|30em}} |

||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

* Moritz, Fred. ''The Landmark Controversy: A Study in Baptist History and Polity'' (The Maranatha Series) (2013); 22pp |

* Moritz, Fred. ''The Landmark Controversy: A Study in Baptist History and Polity'' (The Maranatha Series) (2013); 22pp |

||

| ⚫ | |||

== External links == |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20160415044916/http://www.pbministries.org/History/J.%20R.%20Graves/Old%20Landmarkism/old_landmarkism.htm Old Landmarkism: What Is It?] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

* [http://libcfl.com/articles/witness1.htm Three Witnesses for the Baptists, Curtis Pugh] |

|||

* [http://landmarkism.tripod.com/index.html A Study of the Antecedents of Landmarkism], by LeRoy Benjamin Hogue |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20090303151248/http://thebaptist.org/Perpetuity.htm Perpetuity of the Lord’s Church] |

|||

{{Portal bar|Christianity|Modern history|United States}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Landmarkism| ]] |

|||

[[Category:1851 in Christianity]] |

[[Category:1851 in Christianity]] |

||

[[Category:Anti-Protestantism]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

Landmarkism, sometimes called Baptist bride theology,[1][2] is a Baptist ecclesiology that emerged in the mid-19th century in the American South. It upholds the perpetuity theory of Baptist origins, which asserts an unbroken continuity and exclusive legitimacy of the Baptist movement since the apostolic period. Landmarkists hold a firm belief in the exclusive validity of Baptist churches and view non-Baptist liturgical forms and practices as invalid. This perspective caused significant controversy and division within the Baptist community, leading to intense debates and numerous schisms.

The movement began in the American South in 1851, shaped by James R. Graves of Tennessee,[3][4] and Ben M. Bogard of Arkansas.[5] The movement was a reaction to religious progressivism earlier in the century.[4] At the time it arose, its proponents claimed Landmarkism was a return to what Baptists had previously believed, while scholars since then have claimed it was "a major departure."[3]

In 1859, the Southern Baptist Convention approved several resolutions disapproving of Landmarkism, which led to adherents gradually withdrawing from the Southern Baptist Convention "to form their own churches and associations and create an independent Landmark Baptist tradition."[6]

The main baptist groups adhering to Landmark principles and doctrines in the present day are the churches of the American Baptist Association (founded by Bogard), Baptist Missionary Association of America, and the Interstate & Foreign Landmark Missionary Baptist Association.[7]

Through his Tennessee Baptist newspaper, James R. Graves popularized Landmarkism,[8] building for it a virtual hegemony among Baptists west of the Appalachians. He and Amos C. Dayton, who was also influential, were members of the First Baptist Church of Nashville, Tennessee. He was especially popular in the states of the lower Mississippi River Valley and Texas. In 1851, Graves called a meeting of like-minded Baptists at the Cotton Grove Baptist Church near Jackson, Tennessee, to address five questions:

- Can Baptists with their principles on the Scriptures, consistently recognize those societies not organized according to the Jerusalem church, but possessing different government, different officers, a different class of members, different ordinances, doctrines and practices as churches of Christ?

- Ought they to be called gospel churches or churches in a religious sense?

- Can we consistently recognize the ministers of such irregular and unscriptural bodies as gospel ministers?

- Is it not virtually recognizing them as official ministers to invite them into our pulpits or by any other act that would or could be construed as such recognition?

- Can we consistently address as brethren those professing Christianity who not only have not the doctrine of Christ and walk not according to his commandments but are arrayed in direct and bitter opposition to them?

The majority of the gathered Baptists resolved these questions by non-recognition of non-Baptist congregations, and then published their findings as the "Cotton Grove Resolutions".[9] The "Cotton Grove Resolutions" essentially comprise the organizational document of the Landmark Baptist movement.

James M. Pendleton was a Baptist pastor from Kentucky whose article An Old Landmark Re-Set, a treatise against pulpit affiliation with non-Baptist ministers, gave the movement its name. His Church Manual was also influential in perpetuating Landmark Baptist ecclesiology. Although Pendleton was the only native Southerner in the Landmark Triumvirate, he was in favor of emancipation and opposed secession. As a result, his influence among Southern Baptists declined precipitously in the days leading up to the American Civil War and he took a pastorate in Pennsylvania during the war.[10]

Amos C. Dayton's major contribution to Landmarkism was the novel Theodosia Ernest (1857), which expressed religious issues and was first published in The Tennessee Baptist.[11]

This Christian theology article is a stub. You can help Wikipedia by expanding it. |