|

m Undid revision 156596386 by 68.77.113.94 (talk) Credit is only the right to borrow. What is borrowed is money.

|

|

||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

The operative notion of easy money is that the central bank creates new [[bank reserves]] (in the US known as "[[federal funds]]"), which let the banks lend out more money. These loans get spent, and the proceeds get deposited at other banks. Whatever is not required to be held as reserves is then lent out again, and through the magic of the "money multiplier", loans and bank deposits go up by many times the initial injection of reserves. |

The operative notion of easy money is that the central bank creates new [[bank reserves]] (in the US known as "[[federal funds]]"), which let the banks lend out more money. These loans get spent, and the proceeds get deposited at other banks. Whatever is not required to be held as reserves is then lent out again, and through the magic of the "money multiplier", loans and bank deposits go up by many times the initial injection of reserves. |

||

However in the 1970s the reserve requirements on deposits started to fall with the emergence of [[money market funds]], which require no reserves. Then in the early 1990s, reserve requirements were dropped to zero on [[savings deposit]]s, [[Certificate of deposit|CD]]s, and [[ |

However in the 1970s the reserve requirements on deposits started to fall with the emergence of [[money market funds]], which require no reserves. Then in the early 1990s, reserve requirements were dropped to zero on [[savings deposit]]s, [[Certificate of deposit|CD]]s, and [[Eurodollars|Eurodollar deposit]]. At present, reserve requirements apply only to "[[transactions deposits]]" - essentially [[checking accounts]]. The vast majority of funding sources used by Private Banks to create loans have nothing to do with bank reserves and in effect create what is known as "moral hazard" and speculative bubble economies. |

||

These days, [[commercial and industrial loans]] are financed by issuing large denomination [[Certificate of deposit|CD]]s. [[Money market]] deposits are largely used to lend to corporations who issue [[commercial paper]]. Consumer loans are also made using [[savings deposit]]s which are not subject to reserve requirements. These loans can be bunched into securities and sold to somebody else, taking them off of the bank's books. |

These days, [[commercial and industrial loans]] are financed by issuing large denomination [[Certificate of deposit|CD]]s. [[Money market]] deposits are largely used to lend to corporations who issue [[commercial paper]]. Consumer loans are also made using [[savings deposit]]s which are not subject to reserve requirements. These loans can be bunched into securities and sold to somebody else, taking them off of the bank's books. |

||

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

No issues specified. Please specify issues, or remove this template. |

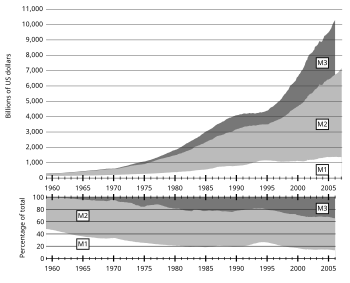

Inmacroeconomics, money supply ("monetary aggregates", "money stock") is the quantity of currency and money in bank accounts in the hands of the non-bank public available within the economy to purchase goods, services, and securities. The rate of interest is the price of money. The two are related inversely, such that, as money supply increases interest rates will fall. When the interest rate equates the quantity of money demanded with the quantity of money supply, the economy is working at the money market equilibrium.

The money demand market uses the same tools of analysis as to other markets: supply and demand result in an equilibrium price, where the free market (orlong term) interest rate plus the quantity of real money available balances the demand for money. Short term rates are artificially manipulated by the Federal Reserve in the open market.

When thinking about the "supply" of money, it is natural to think of the total of banknotes and coins in an economy. That, however, is vastly incomplete. In the United States, coins are minted by the United States Mint, part of the Department of the Treasury, outside of the Federal Reserve. Banknotes are printed by the Bureau of Engraving & Printing on behalf of the Federal Reserve System. The Federal Reserve can also create book-keeping credits in the reserve accounts of its member banks, on the same terms as it can issue paper banknotes (by pledging collateral, usually in the form of US Treasury securities). As it always stands ready to exchange these book-keeping credits for paper banknotes, they are functionally equivalent.

In this respect, all paper banknotes in existence are systematically linked to the expansion of the electronic, credit-based money supply. Coinage can be increased or decreased outside this system by Legal Mandate or Legislative Acts. However, at present the coin base is held in check and used as a complementary system rather than a competitive system with private bank issue of electronic, credit-based money. The common practice is to include printed and minted money supply in the same metric M0.

The more accurate starting point for the concept of money supply is the total of all electronic, credit-based deposit balances in bank (and other financial) accounts (for more precise definitions, see below) plus all the minted coins and printed paper. The M1 money supply is M0, plus the total of (non-paper or coin) deposit balances without any withdrawal restrictions (restricted accounts that you can't write checks on are put in the next level of liquidity, M2).

The relationship between the M0 and M1 money supplies is the money multiplier — basically, the ratio of cash and coin in people's wallets and bank vaults and ATMs to Total balances in their financial accounts. The gap and lag between the two (M0 and M1 - M0) occurs because of the system of fractional-reserve banking.

Because (in principle) money is anything that can be used in settlement of a debt, there are varying measures of money supply. The narrowest (i.e., most restrictive) measures count only those forms of money available for immediate transactions, while broader measures include money held as a store of value

The most common measures are named M0 (narrowest), M1, M2, and M3. In the United States they are defined by the Federal Reserve as follows:

As of March 23, 2006, information regarding M3 will no longer be published by the Federal Reserve, ostensibly because it costs a lot to collect the data but doesn't provide significantly useful data[1]. The other three money supply measures will continue to be provided in detail.

In an effort to reverse this change, Congressman Ron Paul introduced the now expired H.R.4892[2] on March 7th, 2006, and subsequently sponsored H.R.2754[3][4] on June 15th, 2007 which has been referred to the House Committee on Financial Services.

There are just two official UK measures. M0 is referred to as the "wide monetary base" or "narrow money" and M4 is referred to as "broad money" or simply "the money supply".

Money supply is important because it is linked to inflation by the "monetary exchange equation":

where:

In other words, if the money supply grows faster than real GDP growth (described as "unproductive debt expansion"), inflation is likely to follow ("inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon"). This statement must be qualified slightly, due to changes in velocity. While the monetarists presume that velocity is relatively stable, in fact velocity exhibits variability at business-cycle frequencies, so that the velocity equation is not particularly useful as a short run tool. Moreover, in the US, velocity has grown at an average of slightly more than 1% a year between 1959 and 2005 (which is to be expected due to the increase in population, unless money supply grows very rapidly).

In terms of percentage changes (to a small approximation, the percentage change in a product, say XY is equal to the sum of the percentage changes %X + %Y). So:

That equation rearranged gives the "basic inflation identity":

Inflation (%P) is equal to the rate of money growth (%M), plus the change in velocity (%V), minus the rate of output growth (%Y).[6]

In the U.S., as of December, 2006, M1 was about $1.37 trillion and M2 was about $7.02 trillion. If you split all of the money equally per person in the United States, each person would end up with roughly $4,550 ($1,370,000M/301M) using M1 or $23,320 ($7,020,000M/301M) using M2. The amount of actual physical cash, M0, was $749.6 billion in December, 2006, almost three times the $261 billion in cash and cash equivalents on depositatCitigroup as of the end of that year and roughly $2492 per person in the US. [7] [8]

When a central bank is "easing", it triggers an increase in money supply by purchasing government securities on the open market thus increasing available funds for private banks to loan through fractional reserve banking (the issue of new money through loans) and thus grows the money supply. When the central bank is "tightening", it slows the process of private bank issue by selling securities on the open market and pulling money (that could be loaned) out of the private banking sector. It reduces or increases the supply of short term government debt, and inversely increases or reduces the supply of lending funds and thereby the ability of private banks to issue new money through debt.

The operative notion of easy money is that the central bank creates new bank reserves (in the US known as "federal funds"), which let the banks lend out more money. These loans get spent, and the proceeds get deposited at other banks. Whatever is not required to be held as reserves is then lent out again, and through the magic of the "money multiplier", loans and bank deposits go up by many times the initial injection of reserves.

However in the 1970s the reserve requirements on deposits started to fall with the emergence of money market funds, which require no reserves. Then in the early 1990s, reserve requirements were dropped to zero on savings deposits, CDs, and Eurodollar deposit. At present, reserve requirements apply only to "transactions deposits" - essentially checking accounts. The vast majority of funding sources used by Private Banks to create loans have nothing to do with bank reserves and in effect create what is known as "moral hazard" and speculative bubble economies.

These days, commercial and industrial loans are financed by issuing large denomination CDs. Money market deposits are largely used to lend to corporations who issue commercial paper. Consumer loans are also made using savings deposits which are not subject to reserve requirements. These loans can be bunched into securities and sold to somebody else, taking them off of the bank's books.

The point is simple. Commercial, industrial and consumer loans no longer have any link to bank reserves. Since 1995, the volume of such loans has exploded, while bank reserves have declined.

In recent years, the irrelevance of open market operations has also been argued by academic economists renown for their work on the implications of rational expectations, including Robert Lucas, Jr., Thomas Sargent, Neil Wallace, Finn E. Kydland, Edward C. Prescott and Scott Freeman.

Assuming that prices do not instantly adjust to equate supply and demand, one of the principal jobs of central banks is to ensure that aggregate (or overall) demand matches the potential supply of an economy. Central banks can do this because overall demand can be controlled by the money supply. By putting more money into circulation, the central bank can stimulate demand. By taking money out of circulation, the central bank can reduce demand.

For instance, if there is an overall shortfall of demand relative to supply (that is, a given economy can potentially produce more goods than consumers wish to buy) then some resources in the economy will be unemployed (i.e., there will be a recession). In this case the central bank can stimulate demand by increasing the money supply. In theory the extra demand will then lead to job creation for the unemployed resources (people, machines, land), leading back to full employment (more precisely, back to the natural rate of unemployment, which is basically determined by the amount of government regulation and is different in different countries).

However, central banks have a difficult balancing act because, if they print too much money, demand will outstrip an economy's ability to supply so that, even when all resources are employed, demand still cannot be satisfied. In this case, unemployment will fall back to the natural rate and there will then be competition for the last remaining labour, leading to wage rises and inflation. This can then lead to another recession as the central bank takes money out of circulation (raising interest rates in the process) to try and damp down demand.

The main debate amongst economists in the second half of the twentieth century concerned the central banks ability to know how much money to inject into or take out of circulation under different circumstances. Some economists like Milton Friedman believed that the central bank would always get it wrong, leading to wider swings in the economy than if it were just left alone. That is why they advocated a non-interventionist approach.

Current Chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, Ben Bernanke, has suggested that over the last 10 to 15 years, many modern central banks have become relatively adept at manipulation of the money supply, leading to a smoother business cycle, with recessions tending to be smaller and less frequent than in earlier decades, a phenomenon he terms "The Great Moderation" [9].

Central banks operating under a fixed/pegged exchange rate system cannot use the money supply to stimulate demand since the effects on the interest rate would affect the exchange rate. Such central banks generally use inflation targeting, trying to keep a steady and low inflation and hence exchange rate, leaving policy directly affecting the goods and labor market to the government.

Percent change at annual rates M1 M2 M3 12 Months from June 2006 TO June 2007 16.35 -- 16.0 [Source for M1] [Source for M3]

Percent change at annual rates M1 M2 M3 12 Months from June 2006 TO June 2007 9.91 7.44 10.07 [Source]

Percent change at annual rates M1 M2 M3 12 Months from March 2006 TO March 2007 19.98 17.3 -- [Source]

Percent change at seasonally adjusted annual rates M1 M2 M3 12 Months from June 2006 TO June 2007 6.1 -- 10.9 [Source]

Percent change at seasonally adjusted annual rates M1 M2 M3 12 Months from June 2006 TO June 2007 -0.2 1.8 3.6 [Source]

Percent change at seasonally adjusted annual rates M1 M2 M3 12 Months from May 2006 TO May 2007 -- 59.9 -- [Source]

Percent change at seasonally adjusted annual rates M1 M2 M3 12 Months from June 2006 TO June 2007 -4.3 -6.4 2.4 [Source]

Percent change at seasonally adjusted annual rates M1 M2 M3 12 Months from June 2006 TO June 2007 11.95 15.56 15.60 [Source]

Percent change at seasonally adjusted annual rates M1 M2 M3 3 Months from Mar. 2007 TO June 2007 -0.9 5.2 -- 6 Months from Dec. 2006 TO June 2007 0.1 6.3 -- 12 Months from June 2006 TO June 2007 -0.7 6.1 12.0 [Source for M1 and M2] [Source for M3]