|

i wrote stuff

|

m →Characteristics: wikify

|

||

| (24 intermediate revisions by 16 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Type of surface acoustic wave which travels along the surface of solids}} |

|||

| ⚫ |

'''Rayleigh waves''' are a type of [[surface acoustic wave]] that travel along the surface of solids. They can be produced in materials in many ways, such as by a localized impact or by [[Piezoelectricity|piezo-electric]] [[Interdigital transducer|transduction]], and are frequently used in [[non-destructive testing]] for detecting defects. Rayleigh waves are part of the [[seismic wave]]s that are produced on the [[Earth]] by [[earthquakes]]. When guided in layers they are referred to as [[Lamb waves]], Rayleigh–Lamb waves, or generalized Rayleigh waves. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | '''Rayleigh waves''' are a type of [[surface acoustic wave]] that travel along the surface of solids. They can be produced in materials in many ways, such as by a localized impact or by [[Piezoelectricity|piezo-electric]] [[Interdigital transducer|transduction]], and are frequently used in [[non-destructive testing]] for detecting defects. Rayleigh waves are part of the [[seismic wave]]s that are produced on the [[Earth]] by [[earthquakes]]. When guided in layers they are referred to as [[Lamb waves]], Rayleigh–Lamb waves, or generalized Rayleigh waves. |

||

none of this is true, wikipidia is all fake, they are all robots. |

|||

== Characteristics == |

== Characteristics == |

||

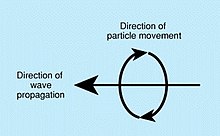

[[File:Rayleigh wave.jpg|thumb|right| |

[[File:Rayleigh wave.jpg|thumb|right|Particle motion of a Rayleigh wave.]] |

||

[[File:Wave speeds of an isotropic elastic medium.png|thumb|right|Comparison of the Rayleigh wave speed with shear and longitudinal wave speeds for an isotropic elastic material. The speeds are shown in dimensionless units.]] |

[[File:Wave speeds of an isotropic elastic medium.png|thumb|right|Comparison of the Rayleigh wave speed with shear and longitudinal wave speeds for an isotropic elastic material. The speeds are shown in dimensionless units.]] |

||

Rayleigh waves are a type of [[surface wave]] that travel near the surface of solids. Rayleigh waves include both longitudinal and transverse motions that decrease exponentially in amplitude as distance from the surface increases. There is a phase difference between these component motions.<ref name="Telford1990"/> |

Rayleigh waves are a type of [[surface wave]] that travel near the surface of solids. Rayleigh waves include both longitudinal and transverse motions that decrease exponentially in amplitude as distance from the surface increases. There is a phase difference between these component motions.<ref name="Telford1990"/> |

||

The existence of Rayleigh waves was predicted in 1885 by [[Lord Rayleigh]], after whom they were named.<ref>http://plms.oxfordjournals.org/content/s1-17/1/4.full.pdf "On Waves Propagated along the Plane Surface of an ElasticSolid", Lord Rayleigh, 1885</ref> In [[isotropic]] solids these waves cause the surface particles to move in [[ellipse]]s in planes normal to the surface and parallel to the direction of propagation – the major axis of the ellipse is vertical. At the surface and at shallow depths this motion is ''retrograde'', that is the in-plane motion of |

The existence of Rayleigh waves was predicted in 1885 by [[Lord Rayleigh]], after whom they were named.<ref>[http://plms.oxfordjournals.org/content/s1-17/1/4.full.pdf ]{{dead link|date=May 2021|bot=medic}}{{cbignore|bot=medic}} "On Waves Propagated along the Plane Surface of an ElasticSolid", Lord Rayleigh, 1885</ref> In [[isotropic]] solids these waves cause the surface particles to move in [[ellipse]]s in planes normal to the surface and parallel to the direction of propagation – the major axis of the ellipse is vertical. At the surface and at shallow depths this motion is ''retrograde'', that is the in-plane motion of a particle is counterclockwise when the wave travels from left to right. At greater depths the particle motion becomes ''prograde''. In addition, the motion amplitude decays and the [[eccentricity (mathematics)|eccentricity]] changes as the depth into the material increases. The depth of significant displacement in the solid is approximately equal to the acoustic [[wavelength]]. Rayleigh waves are distinct from other types of surface or guided [[Acoustics|acoustic]] waves such as [[Love wave]]s or [[Lamb wave]]s, both being types of guided waves supported by a layer, or [[longitudinal waves|longitudinal]] and [[shear waves]], that travel in the bulk. |

||

Rayleigh waves have a speed slightly less than shear waves by a factor dependent on the elastic constants of the material.<ref name="Telford1990"/> The typical speed of Rayleigh waves in metals is of the order of 2–5 km/s, and the typical Rayleigh speed in the ground is of the order of 50–300 m/s |

Rayleigh waves have a speed slightly less than shear waves by a factor dependent on the elastic constants of the material.<ref name="Telford1990"/> The typical speed of Rayleigh waves in metals is of the order of 2–5 km/s, and the typical Rayleigh speed in the ground is of the order of 50–300 m/s for shallow waves less than 100-m depth and 1.5–4 km/s at depths greater than1 km. Since Rayleigh waves are confined near the surface, their in-plane amplitude when generated by a point source decays only as <math>{1}/{\sqrt{r}}</math>, where <math>r</math> is the radial distance. Surface waves therefore decay more slowly with distance than do bulk waves, which spread out in three dimensions from a point source. This slow decay is one reason why they are of particular interest to seismologists. Rayleigh waves can circle the globe multiple times after a large earthquake and still be measurably large. There is a difference in the behavior (Rayleigh wave velocity, displacements, trajectories of the particle motion, stresses) of Rayleigh surface waves with positive and negative [[Poisson's ratio]].<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Goldstein|first1=R.V.|last2=Gorodtsov|first2=V.A.|last3=Lisovenko|first3=D.S.|date=2014|title=Rayleigh and Love surface waves in isotropic media with negative Poisson's ratio|journal=Mechanics of Solids|language=en|volume=49|issue=4|pages=422–434|doi=10.3103/S0025654414040074|bibcode=2014MeSol..49..422G|s2cid=121607244}}</ref> |

||

In seismology, Rayleigh waves (called "ground roll") are the most important type of surface wave, and can be produced (apart from earthquakes), for example, by [[wind wave|ocean waves]], |

In seismology, Rayleigh waves (called "ground roll") are the most important type of surface wave, and can be produced (apart from earthquakes), for example, by [[wind wave|ocean waves]], by explosions, by railway trains and ground vehicles, or by a sledgehammer impact.<ref name="Telford1990">{{cite book|last1=Telford|first1=William Murray|last2=Geldart|first2=L. P.|author3=Robert E. Sheriff|title=Applied geophysics|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oRP5fZYjhXMC&pg=PA149|access-date=8 June 2011|year=1990|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-33938-4|page=149}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | last=Longuet-Higgins | first=M. S. | title=A Theory of the OriginofMicroseisms | journal=Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences | publisher=The Royal Society | volume=243 | issue=857 | date=1950-09-27 | issn=1364-503X | doi=10.1098/rsta.1950.0012 | pages=1–35| bibcode=1950RSPTA.243....1L | s2cid=31828394 }}</ref> |

||

=== |

=== Speed and dispersion === |

||

[[File:DispersionRayleighWave.jpg|right|thumb|Dispersion of Rayleigh waves in a thin gold film on glass.[http://kino-ap.eng.hokudai.ac.jp/index.html]]] |

[[File:DispersionRayleighWave.jpg|right|thumb|Dispersion of Rayleigh waves in a thin gold film on glass.[http://kino-ap.eng.hokudai.ac.jp/index.html]]] |

||

In isotropic, linear elastic materials described by Lamé |

In isotropic, linear elastic materials described by [[Lamé parameters]] <math> \lambda </math> and <math> \mu </math>, Rayleigh waves have a speed given by solutions to the equation |

||

:<math> \zeta^3 -8 \zeta^2 + 8 \zeta (3-2\eta) - 16 (1-\eta) = 0, </math> |

:<math> \zeta^3 -8 \zeta^2 + 8 \zeta (3-2\eta) - 16 (1-\eta) = 0, </math> |

||

where <math> \zeta = \omega^2 / k^2 \beta^2 </math>, <math> \eta = \beta^2/\alpha^2</math>, <math> \rho \alpha^2 = \lambda + 2 \mu </math>, and <math> \rho \beta^2 = \mu </math>.<ref name=LL>{{cite book |title=Theory of Elasticity |edition=3rd|last=Landau |first=L.D. | |

where <math> \zeta = \omega^2 / k^2 \beta^2 </math>, <math> \eta = \beta^2/\alpha^2</math>, <math> \rho \alpha^2 = \lambda + 2 \mu </math>, and <math> \rho \beta^2 = \mu </math>.<ref name=LL>{{cite book |title=Theory of Elasticity |edition=3rd|last=Landau |first=L.D. |author-link=Lev Landau |author2=Lifshitz, E. M. |author-link2= Evgeny Lifshitz |year=1986 |publisher=Butterworth Heinemann |location=Oxford, England |isbn=978-0-7506-2633-0 }}</ref> |

||

Since this equation has no inherent scale, the boundary value problem giving rise to Rayleigh waves are dispersionless. |

Since this equation has no inherent scale, the [[boundary value problem]] giving rise to Rayleigh waves are dispersionless. |

||

An interesting special case is the Poisson solid, for which <math> \lambda = \mu</math>, since this gives a frequency-independent phase velocity equal to <math> \omega/k = \beta \sqrt{0.8453}</math>. |

An interesting special case is the Poisson solid, for which <math> \lambda = \mu</math>, since this gives a frequency-independent phase velocity equal to <math> \omega/k = \beta \sqrt{0.8453}</math>. For linear elastic materials with positive Poisson ratio (<math>\nu > 0.3</math>), the Rayleigh wave speed can be approximated as <math>c_R = c_S \frac{0.862 + 1.14 \nu}{1+\nu}</math>, where <math>c_S</math> is the shear-wave velocity.<ref name="Freund1990">{{cite book|author1=L. B. Freund|title=Dynamic Fracture Mechanics|year=1998|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0521629225|page=83}}</ref> |

||

The elastic constants often change with depth, due to the changing properties of the material. This means that the velocity of a Rayleigh wave in practice becomes dependent on the [[wavelength]] (and therefore [[frequency]]), a phenomenon referred to as [[Velocity dispersion|dispersion]]. Waves affected by dispersion have a different [[wave train]] shape.<ref name="Telford1990"/> Rayleigh waves on ideal, homogeneous and flat elastic solids show no dispersion, as stated above. However, if a solid or structure has a [[density]] or [[sound velocity]] that varies with depth, Rayleigh waves become dispersive. One example is Rayleigh waves on the Earth's surface: those waves with a higher [[frequency]] travel more slowly than those with a lower frequency. This occurs because a Rayleigh wave of lower frequency has a relatively long [[wavelength]]. The displacement of long wavelength waves penetrates more deeply into the Earth than short wavelength waves. Since the speed of waves in the Earth increases with increasing depth, the longer wavelength ([[low frequency]]) waves can travel faster than the shorter wavelength ([[high frequency]]) waves. Rayleigh waves thus often appear spread out on [[seismogram]]s recorded at distant earthquake recording stations. It is also possible to observe Rayleigh wave dispersion in thin films or multi-layered structures. |

The elastic constants often change with depth, due to the changing properties of the material. This means that the velocity of a Rayleigh wave in practice becomes dependent on the [[wavelength]] (and therefore [[frequency]]), a phenomenon referred to as [[Velocity dispersion|dispersion]]. Waves affected by dispersion have a different [[wave train]] shape.<ref name="Telford1990"/> Rayleigh waves on ideal, homogeneous and flat elastic solids show no dispersion, as stated above. However, if a solid or structure has a [[density]] or [[sound velocity]] that varies with depth, Rayleigh waves become dispersive. One example is Rayleigh waves on the Earth's surface: those waves with a higher [[frequency]] travel more slowly than those with a lower frequency. This occurs because a Rayleigh wave of lower frequency has a relatively long [[wavelength]]. The displacement of long wavelength waves penetrates more deeply into the Earth than short wavelength waves. Since the speed of waves in the Earth increases with increasing depth, the longer wavelength ([[low frequency]]) waves can travel faster than the shorter wavelength ([[high frequency]]) waves. Rayleigh waves thus often appear spread out on [[seismogram]]s recorded at distant earthquake recording stations. It is also possible to observe Rayleigh wave dispersion in thin films or multi-layered structures. |

||

== |

==In non-destructive testing== |

||

Rayleigh waves are widely used for materials characterization, to discover the mechanical and structural properties of the object being tested – like the presence of cracking, and the related shear modulus. This is in common with other types of surface waves.<ref name="ThompsonChimenti1997">{{cite book|last1=Thompson|first1=Donald O.|last2=Chimenti|first2=Dale E.|title=Review of progress in quantitative nondestructive evaluation|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3etLzmHu6bQC&pg=PA161| |

Rayleigh waves are widely used for materials characterization, to discover the mechanical and structural properties of the object being tested – like the presence of cracking, and the related shear modulus. This is in common with other types of surface waves.<ref name="ThompsonChimenti1997">{{cite book|last1=Thompson|first1=Donald O.|last2=Chimenti|first2=Dale E.|title=Review of progress in quantitative nondestructive evaluation|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3etLzmHu6bQC&pg=PA161|access-date=8 June 2011|date=1 June 1997|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-0-306-45597-1|page=161}}</ref> The Rayleigh waves used for this purpose are in the [[Ultrasound|ultrasonic]] frequency range. |

||

They are used at different length scales because they are easily generated and detected on the free surface of solid objects. Since they are confined in the vicinity of the free surface within a depth (~ the wavelength) linked to the [[frequency]] of the wave, different frequencies can be used for characterization at different length scales. |

They are used at different length scales because they are easily generated and detected on the free surface of solid objects. Since they are confined in the vicinity of the free surface within a depth (~ the wavelength) linked to the [[frequency]] of the wave, different frequencies can be used for characterization at different length scales. |

||

== |

==In electronic devices== |

||

Rayleigh waves propagating at high ultrasonic frequencies (10–1000 MHz) are used widely in different electronic devices.<ref name="Oliner1978">{{cite book|last=Oliner|first=A.A. |

Rayleigh waves propagating at high ultrasonic frequencies (10–1000 MHz) are used widely in different electronic devices.<ref name="Oliner1978">{{cite book|editor-last=Oliner|editor-first=A.A.|editor-link=Arthur A. Oliner|title=Acoustic Surface Waves|year=1978|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-3540085751}}</ref> In addition to Rayleigh waves, some other types of surface acoustic waves (SAW), e.g. [[Love waves]], are also used for this purpose. Examples of electronic devices using Rayleigh waves are [[Electronic filter|filter]]s, resonators, oscillators, [[sensors]] of pressure, temperature, humidity, etc. Operation of SAW devices is based on the transformation of the initial electric signal into a surface wave that, after achieving the required changes to the spectrum of the initial electric signal as a result of its interaction with different types of surface inhomogeneity,<ref name="Biryukov1995">{{cite book|last1=Biryukov|first1=S.V.|last2=Gulyaev|first2=Y.V.|last3=Krylov|first3=V.V.|last4=Plessky|first4=V.P.|title=Surface Acoustic Waves in Inhomogeneous Media|year=1995|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-3-642-57767-3}}</ref> is transformed back into a modified electric signal. The transformation of the initial electric energy into mechanical energy (in the form of SAW) and back is usually accomplished via the use of [[piezoelectric]] materials for both generation and reception of Rayleigh waves as well as for their propagation. |

||

== |

== In geophysics == |

||

=== |

=== Generation from earthquakes=== |

||

Because Rayleigh waves are surface waves, the [[amplitude]] of such waves generated by an earthquake generally decreases exponentially with the depth of the [[hypocenter]] (focus). However, |

Because Rayleigh waves are surface waves, the [[amplitude]] of such waves generated by an earthquake generally decreases exponentially with the depth of the [[hypocenter]] (focus). However, large earthquakes may generate Rayleigh waves that travel around the Earth several times before dissipating. |

||

In seismology longitudinal and shear waves are known as [[P-wave]]s and [[S-wave]]s, respectively, and are termed body waves. Rayleigh waves are generated by the interaction of P- and S- waves at the surface of the earth, and travel with a velocity that is lower than the P-, S-, and Love wave velocities. Rayleigh waves emanating outward from the epicenter of an earthquake |

In seismology longitudinal and shear waves are known as [[P-wave]]s and [[S-wave]]s, respectively, and are termed body waves. Rayleigh waves are generated by the interaction of P- and S- waves at the surface of the earth, and travel with a velocity that is lower than the P-, S-, and Love wave velocities. Rayleigh waves emanating outward from the epicenter of an earthquake travel along the surface of the earth at about 10 times the [[speed of sound]] in air (0.340 km/s), that is ~3 km/s. |

||

Due to their higher speed, the P- and S-waves generated by an earthquake arrive before the surface waves. However, the particle motion of surface waves is larger than that of body waves, so the surface waves tend to cause more damage. In the case of Rayleigh waves, the motion is of a rolling nature, similar to an [[ocean surface wave]]. The intensity of Rayleigh wave shaking at a particular location is dependent on several factors: |

Due to their higher speed, the P- and S-waves generated by an earthquake arrive before the surface waves. However, the particle motion of surface waves is larger than that of body waves, so the surface waves tend to cause more damage. In the case of Rayleigh waves, the motion is of a rolling nature, similar to an [[ocean surface wave]]. The intensity of Rayleigh wave shaking at a particular location is dependent on several factors: |

||

| Line 58: | Line 58: | ||

Local geologic structure can serve to focus or defocus Rayleigh waves, leading to significant differences in shaking over short distances. |

Local geologic structure can serve to focus or defocus Rayleigh waves, leading to significant differences in shaking over short distances. |

||

=== |

===In seismology=== |

||

Low frequency Rayleigh waves generated during [[earthquakes]] are used in [[seismology]] to characterise the [[Earth]]'s interior. |

Low frequency Rayleigh waves generated during [[earthquakes]] are used in [[seismology]] to characterise the [[Earth]]'s interior. |

||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

{{further|Infrasound#Animal reaction|Tsunami#Possible animal reaction}} |

{{further|Infrasound#Animal reaction|Tsunami#Possible animal reaction}} |

||

[[Low frequency]] (< 20 Hz) Rayleigh waves are inaudible, yet they can be detected by many [[mammal]]s, [[bird]]s, [[insect]]s and [[spider]]s. Humans should be able to detect such Rayleigh waves through their [[Pacinian corpuscle]]s, which are in the joints, although people do not seem to consciously respond to the signals. Some animals seem to use Rayleigh waves to communicate. In particular, some biologists theorize that [[elephant]]s may use vocalizations to generate Rayleigh waves. Since Rayleigh waves decay slowly, they should be detectable over long distances.<ref>{{cite journal | |

[[Low frequency]] (< 20 Hz) Rayleigh waves are inaudible, yet they can be detected by many [[mammal]]s, [[bird]]s, [[insect]]s and [[spider]]s. Humans should be able to detect such Rayleigh waves through their [[Pacinian corpuscle]]s, which are in the joints, although people do not seem to consciously respond to the signals. Some animals seem to use Rayleigh waves to communicate. In particular, some biologists theorize that [[elephant]]s may use vocalizations to generate Rayleigh waves. Since Rayleigh waves decay slowly, they should be detectable over long distances.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=O’Connell-Rodwell |first1=C.E.|first2 = B.T.|last2 =Arnason |first3 = L.A.|last3 =Hart |date= 14 September 2000 |title= Seismic properties of Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) vocalizations and locomotion |journal= J. Acoust. Soc. Am. |volume= 108|issue=6 |pages=3066–3072 |doi= 10.1121/1.1323460 |pmid=11144599|bibcode=2000ASAJ..108.3066O}}</ref> Note that these Rayleigh waves have a much higher frequency than Rayleigh waves generated by earthquakes. |

||

After the [[2004 Indian Ocean earthquake]], some people have speculated that Rayleigh waves served as a warning to animals to seek higher ground, allowing them to escape the more slowly traveling [[tsunami]]. At this time, evidence for this is mostly anecdotal. Other animal early warning systems may rely on an ability to sense [[infrasound|infrasonic]] waves traveling through the air.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/explainer/2004/12/surviving_the_tsunami.html|title=Surviving the Tsunami |last1=Kenneally |first1=Christine |date= 30 December 2004 |website=www.slate.com | |

After the [[2004 Indian Ocean earthquake]], some people have speculated that Rayleigh waves served as a warning to animals to seek higher ground, allowing them to escape the more slowly traveling [[tsunami]]. At this time, evidence for this is mostly anecdotal. Other animal early warning systems may rely on an ability to sense [[infrasound|infrasonic]] waves traveling through the air.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/explainer/2004/12/surviving_the_tsunami.html|title=Surviving the Tsunami |last1=Kenneally |first1=Christine |date= 30 December 2004 |website=www.slate.com |access-date=26 November 2013}}</ref> |

||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

| Line 81: | Line 81: | ||

* [[Surface acoustic wave]] |

* [[Surface acoustic wave]] |

||

== |

==References== |

||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist}} |

||

| Line 87: | Line 87: | ||

*Viktorov, I.A. (2013) "Rayleigh and Lamb Waves: Physical Theory and Applications", Springer; Reprint of the original 1st 1967 edition by Plenum Press, New York. {{ISBN|978-1489956835}}. |

*Viktorov, I.A. (2013) "Rayleigh and Lamb Waves: Physical Theory and Applications", Springer; Reprint of the original 1st 1967 edition by Plenum Press, New York. {{ISBN|978-1489956835}}. |

||

*Aki, K. and Richards, P. G. (2002). ''Quantitative Seismology'' (2nd ed.). University Science Books. {{ISBN|0-935702-96-2}}. |

*Aki, K. and Richards, P. G. (2002). ''Quantitative Seismology'' (2nd ed.). University Science Books. {{ISBN|0-935702-96-2}}. |

||

*[[Mary Fowler|Fowler, C. M. R.]] (1990). ''The Solid Earth''. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. {{ISBN|0-521-38590-3}}. |

*[[Mary Fowler (geologist)|Fowler, C. M. R.]] (1990). ''The Solid Earth''. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. {{ISBN|0-521-38590-3}}. |

||

*Lai, C.G., Wilmanski, K. (Eds.) (2005). ''Surface Waves in Geomechanics: Direct and Inverse Modelling for Soils and Rocks |

*Lai, C.G., Wilmanski, K. (Eds.) (2005). ''Surface Waves in Geomechanics: Direct and Inverse Modelling for Soils and Rocks'' Series: CISM International Centre for Mechanical Sciences, Number 481, Springer, Wien, {{ISBN|978-3-211-27740-9}} |

||

*{{cite journal | last1=Sugawara | first1=Y. | last2=Wright | first2=O. B. | last3=Matsuda | first3=O. | last4=Takigahira | first4=M. | last5=Tanaka | first5=Y. | last6=Tamura | first6=S. | last7=Gusev | first7=V. E. | title=Watching Ripples on Crystals | journal=Physical Review Letters | publisher=American Physical Society (APS) | volume=88 | issue=18 | date=2002-04-18 | issn=0031-9007 | doi=10.1103/physrevlett.88.185504 | page=185504| pmid=12005696 | bibcode=2002PhRvL..88r5504S | hdl=2115/5791 | hdl-access=free }} |

|||

*Y. Sugawara, O. B. Wright, O. Matsuda, M. Takigahira, Y. Tanaka, S. Tamura and V. E. Gusev, "Watching ripples on crystals", [http://prola.aps.org/abstract/PRL/v88/i18/e185504 Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 185504 (2002)] |

|||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

* [http://kino-ap.eng.hokudai.ac.jp/ripples.html Real-time imaging of Rayleigh waves] |

* [http://kino-ap.eng.hokudai.ac.jp/ripples.html Real-time imaging of Rayleigh waves] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Acoustics]] |

[[Category:Acoustics]] |

||

[[Category:Seismology]] |

[[Category:Seismology]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Surface waves]] |

||

[[Category:Waves]] |

[[Category:Waves]] |

||

Rayleigh waves are a type of surface acoustic wave that travel along the surface of solids. They can be produced in materials in many ways, such as by a localized impact or by piezo-electric transduction, and are frequently used in non-destructive testing for detecting defects. Rayleigh waves are part of the seismic waves that are produced on the Earthbyearthquakes. When guided in layers they are referred to as Lamb waves, Rayleigh–Lamb waves, or generalized Rayleigh waves.

Rayleigh waves are a type of surface wave that travel near the surface of solids. Rayleigh waves include both longitudinal and transverse motions that decrease exponentially in amplitude as distance from the surface increases. There is a phase difference between these component motions.[1]

The existence of Rayleigh waves was predicted in 1885 by Lord Rayleigh, after whom they were named.[2]Inisotropic solids these waves cause the surface particles to move in ellipses in planes normal to the surface and parallel to the direction of propagation – the major axis of the ellipse is vertical. At the surface and at shallow depths this motion is retrograde, that is the in-plane motion of a particle is counterclockwise when the wave travels from left to right. At greater depths the particle motion becomes prograde. In addition, the motion amplitude decays and the eccentricity changes as the depth into the material increases. The depth of significant displacement in the solid is approximately equal to the acoustic wavelength. Rayleigh waves are distinct from other types of surface or guided acoustic waves such as Love wavesorLamb waves, both being types of guided waves supported by a layer, or longitudinal and shear waves, that travel in the bulk.

Rayleigh waves have a speed slightly less than shear waves by a factor dependent on the elastic constants of the material.[1] The typical speed of Rayleigh waves in metals is of the order of 2–5 km/s, and the typical Rayleigh speed in the ground is of the order of 50–300 m/s for shallow waves less than 100-m depth and 1.5–4 km/s at depths greater than 1 km. Since Rayleigh waves are confined near the surface, their in-plane amplitude when generated by a point source decays only as

In seismology, Rayleigh waves (called "ground roll") are the most important type of surface wave, and can be produced (apart from earthquakes), for example, by ocean waves, by explosions, by railway trains and ground vehicles, or by a sledgehammer impact.[1][4]

In isotropic, linear elastic materials described by Lamé parameters

where

The elastic constants often change with depth, due to the changing properties of the material. This means that the velocity of a Rayleigh wave in practice becomes dependent on the wavelength (and therefore frequency), a phenomenon referred to as dispersion. Waves affected by dispersion have a different wave train shape.[1] Rayleigh waves on ideal, homogeneous and flat elastic solids show no dispersion, as stated above. However, if a solid or structure has a densityorsound velocity that varies with depth, Rayleigh waves become dispersive. One example is Rayleigh waves on the Earth's surface: those waves with a higher frequency travel more slowly than those with a lower frequency. This occurs because a Rayleigh wave of lower frequency has a relatively long wavelength. The displacement of long wavelength waves penetrates more deeply into the Earth than short wavelength waves. Since the speed of waves in the Earth increases with increasing depth, the longer wavelength (low frequency) waves can travel faster than the shorter wavelength (high frequency) waves. Rayleigh waves thus often appear spread out on seismograms recorded at distant earthquake recording stations. It is also possible to observe Rayleigh wave dispersion in thin films or multi-layered structures.

Rayleigh waves are widely used for materials characterization, to discover the mechanical and structural properties of the object being tested – like the presence of cracking, and the related shear modulus. This is in common with other types of surface waves.[7] The Rayleigh waves used for this purpose are in the ultrasonic frequency range.

They are used at different length scales because they are easily generated and detected on the free surface of solid objects. Since they are confined in the vicinity of the free surface within a depth (~ the wavelength) linked to the frequency of the wave, different frequencies can be used for characterization at different length scales.

Rayleigh waves propagating at high ultrasonic frequencies (10–1000 MHz) are used widely in different electronic devices.[8] In addition to Rayleigh waves, some other types of surface acoustic waves (SAW), e.g. Love waves, are also used for this purpose. Examples of electronic devices using Rayleigh waves are filters, resonators, oscillators, sensors of pressure, temperature, humidity, etc. Operation of SAW devices is based on the transformation of the initial electric signal into a surface wave that, after achieving the required changes to the spectrum of the initial electric signal as a result of its interaction with different types of surface inhomogeneity,[9] is transformed back into a modified electric signal. The transformation of the initial electric energy into mechanical energy (in the form of SAW) and back is usually accomplished via the use of piezoelectric materials for both generation and reception of Rayleigh waves as well as for their propagation.

Because Rayleigh waves are surface waves, the amplitude of such waves generated by an earthquake generally decreases exponentially with the depth of the hypocenter (focus). However, large earthquakes may generate Rayleigh waves that travel around the Earth several times before dissipating.

In seismology longitudinal and shear waves are known as P-waves and S-waves, respectively, and are termed body waves. Rayleigh waves are generated by the interaction of P- and S- waves at the surface of the earth, and travel with a velocity that is lower than the P-, S-, and Love wave velocities. Rayleigh waves emanating outward from the epicenter of an earthquake travel along the surface of the earth at about 10 times the speed of sound in air (0.340 km/s), that is ~3 km/s.

Due to their higher speed, the P- and S-waves generated by an earthquake arrive before the surface waves. However, the particle motion of surface waves is larger than that of body waves, so the surface waves tend to cause more damage. In the case of Rayleigh waves, the motion is of a rolling nature, similar to an ocean surface wave. The intensity of Rayleigh wave shaking at a particular location is dependent on several factors:

Local geologic structure can serve to focus or defocus Rayleigh waves, leading to significant differences in shaking over short distances.

Low frequency Rayleigh waves generated during earthquakes are used in seismology to characterise the Earth's interior. In intermediate ranges, Rayleigh waves are used in geophysics and geotechnical engineering for the characterisation of oil deposits. These applications are based on the geometric dispersion of Rayleigh waves and on the solution of an inverse problem on the basis of seismic data collected on the ground surface using active sources (falling weights, hammers or small explosions, for example) or by recording microtremors. Rayleigh ground waves are important also for environmental noise and vibration control since they make a major contribution to traffic-induced ground vibrations and the associated structure-borne noise in buildings.

Low frequency (< 20 Hz) Rayleigh waves are inaudible, yet they can be detected by many mammals, birds, insects and spiders. Humans should be able to detect such Rayleigh waves through their Pacinian corpuscles, which are in the joints, although people do not seem to consciously respond to the signals. Some animals seem to use Rayleigh waves to communicate. In particular, some biologists theorize that elephants may use vocalizations to generate Rayleigh waves. Since Rayleigh waves decay slowly, they should be detectable over long distances.[10] Note that these Rayleigh waves have a much higher frequency than Rayleigh waves generated by earthquakes.

After the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, some people have speculated that Rayleigh waves served as a warning to animals to seek higher ground, allowing them to escape the more slowly traveling tsunami. At this time, evidence for this is mostly anecdotal. Other animal early warning systems may rely on an ability to sense infrasonic waves traveling through the air.[11]