|

edit phonotactics to agree with rest of phonology that all phonemes can be long/geminate

Tags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit

|

m Moving Category:Tuvaluan culturetoCategory:Culture of Tuvalu per Wikipedia:Categories for discussion/Speedy

|

||

| (25 intermediate revisions by 16 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{About|the languages of Tuvalu|other uses|Tuvaluan (disambiguation)}} |

{{About|the languages of Tuvalu|other uses|Tuvaluan (disambiguation)}} |

||

{{Short description|Polynesian language spoken in Tuvalu}} |

{{Short description|Polynesian language spoken in Tuvalu}} |

||

{{use dmy dates|date=February 2024}} |

|||

{{Infobox language |

{{Infobox language |

||

| name = Tuvaluan |

| name = Tuvaluan |

||

| Line 13: | Line 14: | ||

| fam3 = [[Oceanic languages|Oceanic]] |

| fam3 = [[Oceanic languages|Oceanic]] |

||

| fam4 = [[Polynesian languages|Polynesian]] |

| fam4 = [[Polynesian languages|Polynesian]] |

||

| fam5 = |

| fam5 = [[Ellicean languages|Ellicean]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

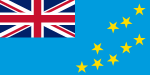

| nation = {{flag|Tuvalu}} |

| nation = {{flag|Tuvalu}} |

||

| script = [[Latin script]] |

| script = [[Latin script]] |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

| notice = IPA |

| notice = IPA |

||

| ietf = tvl-TV |

| ietf = tvl-TV |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| mapcaption = {{center|{{small|Tuvaluan is classified as Definitely Endangered by the [[UNESCO]] [[Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger]]}}}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Culture of Tuvalu}} |

{{Culture of Tuvalu}} |

||

[[File:WIKITONGUES- Paulo speaking Tuvaluan.webm|thumb|Recording of Paulo, a speaker of Tuvaluan]] |

[[File:WIKITONGUES- Paulo speaking Tuvaluan.webm|thumb|Recording of Paulo, a speaker of Tuvaluan]] |

||

'''Tuvaluan''' ({{IPAc-en|t|uː|v|ə|ˈ|l|uː| |

'''Tuvaluan''' ({{IPAc-en|ˌ|t|uː|v|ə|ˈ|l|uː|ə|n}}),<ref>{{cite book |first=Laurie |last=Bauer |year=2007 |title=The Linguistics Student's Handbook |location=Edinburgh}}</ref> often called '''Tuvalu''', is a [[Polynesian languages|Polynesian language]] closely related to the [[Ellicean languages|Ellicean group]] spoken in [[Tuvalu]]. It is more or less distantly related to all other Polynesian languages, such as [[Hawaiian language|Hawaiian]], [[Māori language|Māori]], [[Tahitian language|Tahitian]], [[Samoan language|Samoan]], [[Tokelauan language|Tokelauan]] and [[Tongan language|Tongan]], and most closely related to the languages spoken on the [[Polynesian Outliers]] in [[Micronesia]] and Northern and Central [[Melanesia]]. Tuvaluan has borrowed considerably from Samoan, the language of Christian missionaries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.<ref name="Omniglot">{{cite web |first=Simon |last=Ager | url= http://www.omniglot.com/writing/tuvaluan.htm|title= Tuvaluan (Te 'gana Tūvalu) |publisher=Omniglot|access-date=6 November 2012}}</ref><ref name="MD">{{cite book|first=D. |last= Munro |title = Samoan Pastors in Tuvalu, 1865-1899 |year=1996 |publisher=Suva, Fiji, Pacific Theological College and the University of the South Pacific |pages=124–157 |editor-first=D. |editor-last=Munro |editor-first2=A. |editor-last2=Thornley |chapter=The Covenant Makers: Islander Missionaries in the Pacific }}</ref> |

||

The population of Tuvalu is approximately 10,645 people (2017 Mini Census)<ref name="MDG">{{cite web| |

The population of Tuvalu is approximately 10,645 people (2017 Mini Census),<ref name="MDG">{{cite web| author1= Ministry of Education and Sports |author2=Ministry of Finance and Economic Development |author3=United Nations System in the Pacific Islands |title= Tuvalu: Millennium Development Goal Acceleration Framework – Improving Quality of Education |date =April 2013|url= http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/MDG/MDG%20Acceleration%20Framework/MAF%20Reports/RBAP/MAF%20Tuvalu-FINAL-%20April%204.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140213133607/http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/MDG/MDG%20Acceleration%20Framework/MAF%20Reports/RBAP/MAF%20Tuvalu-FINAL-%20April%204.pdf |archive-date=2014-02-13 |url-status=live| access-date=13 October 2013}}</ref> but there are estimated to be more than 13,000 Tuvaluan speakers worldwide. In 2015 it was estimated that more than 3,500 Tuvaluans live in [[New Zealand]], with about half that number born in New Zealand and 65 percent of the [[Tuvaluan New Zealander|Tuvaluan community in New Zealand]] is able to speak Tuvaluan.<ref name="TV3">{{cite web| website=TV3 |publisher=MediaWorks TV |title= Tuvalu Language Week kicks off today |date =27 September 2015|url= https://www.3news.co.nz/nznews/tuvalu-language-week-kicks-off-today-2015092712| access-date=27 September 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150928002811/https://www.3news.co.nz/nznews/tuvalu-language-week-kicks-off-today-2015092712 |archive-date=2015-09-28}}</ref> |

||

== Name variations == |

== Name variations == |

||

Native speakers of Tuvaluan have various names for their language. In the language itself, it is often referred to as {{lang|tvl|te ggana Tuuvalu}} which translates to "the Tuvaluan language", or less formally as {{lang|tvl|te ggana a tatou}}, meaning "our language". |

Native speakers of Tuvaluan have various names for their language. In the language itself, it is often referred to as {{lang|tvl|te ggana Tuuvalu}} which translates to "the Tuvaluan language", or less formally as {{lang|tvl|te ggana a tatou}}, meaning "our language".{{sfn|Besnier|2000|p=xxi}} The dialects of Vaitupi and Funafuti are together known as a standard language called {{lang|tvl|te 'gana māsani}}, meaning ‘the common language’.<ref name="Omniglot"/>Formerly, the country of Tuvalu was known as the Ellice Islands and the Tuvaluan language is also therefore known as ''Ellice'' or ''Ellicean.''<ref>{{Cite web|website=Catalogue of Endangered Languages|date=2020|title=Tuvaluan|url=http://www.endangeredlanguages.com/lang/3487.|access-date=November 16, 2020}}</ref> |

||

== History == |

== History == |

||

| Line 37: | Line 39: | ||

== Language influences == |

== Language influences == |

||

Tuvaluan has had significant contact with [[Gilbertese language|Gilbertese]], a [[Micronesian languages|Micronesian language]]; [[Samoan language|Samoan]]; and, increasingly, [[English language|English]]. Gilbertese is spoken natively on Nui, and was important to Tuvaluans when its colonial administration was located in the [[Gilbert Islands]]. Samoan was introduced by missionaries, and has had the most impact on the language. During an intense period of colonization throughout Oceania in the nineteenth century, the Tuvaluan language was influenced by Samoan missionary-pastors. In an attempt to "Christianize" Tuvaluans, linguistic promotion of the Samoan language was evident in its use for official government acts and literacy instruction, as well as within the church, until being replaced by the Tuvaluan language in the 1950s.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Barbosa da Silva|first=Diego|date=September 2019|title= |

Tuvaluan has had significant contact with [[Gilbertese language|Gilbertese]], a [[Micronesian languages|Micronesian language]]; [[Samoan language|Samoan]]; and, increasingly, [[English language|English]]. Gilbertese is spoken natively on Nui, and was important to Tuvaluans when its colonial administration was located in the [[Gilbert Islands]]. Samoan was introduced by missionaries, and has had the most impact on the language. During an intense period of colonization throughout Oceania in the nineteenth century, the Tuvaluan language was influenced by Samoan missionary-pastors. In an attempt to "Christianize" Tuvaluans, linguistic promotion of the Samoan language was evident in its use for official government acts and literacy instruction, as well as within the church, until being replaced by the Tuvaluan language in the 1950s.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Barbosa da Silva|first=Diego|date=September 2019|title=Política Linguística na Oceania: Nas fronteiras da colonização e da globalização |journal=Alfa: Revista de Linguística |volume=63|issue=2|pages=317–347|doi=10.1590/1981-5794-1909-4|issn=1981-5794|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ |

English's influence has been limited, but is growing. Since gaining political independence in the 1970s, knowledge of the English language has gained importance for economic viability in Tuvalu. The ability to speak English is important for foreign communications and is often the language used in business and governmental settings. |

||

| ⚫ | English's influence has been limited, but is growing. Since gaining political independence in the 1970s, knowledge of the English language has gained importance for economic viability in Tuvalu. The ability to speak English is important for foreign communications and is often the language used in business and governmental settings.{{sfn|Besnier|2000}} |

||

== Phonology == |

== Phonology == |

||

| Line 60: | Line 61: | ||

|{{IPA link|i}} |

|{{IPA link|i}} |

||

|{{IPA link|u}} |

|{{IPA link|u}} |

||

|{{IPA|iː}} |

|{{IPA link|iː}} |

||

|{{IPA|uː}} |

|{{IPA link|uː}} |

||

|- |

|- |

||

![[Mid vowel|Mid]] |

![[Mid vowel|Mid]] |

||

|{{IPA link|e}} |

|{{IPA link|e}} |

||

|{{IPA link|o}} |

|{{IPA link|o}} |

||

|{{IPA|eː}} |

|{{IPA link|eː}} |

||

|{{IPA|oː}} |

|{{IPA link|oː}} |

||

|- |

|- |

||

![[Open vowel|Open]] |

![[Open vowel|Open]] |

||

| colspan="2" |{{IPA link|a}} |

| colspan="2" |{{IPA link|a}} |

||

| colspan="2" |{{IPA|aː}} |

| colspan="2" |{{IPA link|aː}} |

||

|} |

|} |

||

There are no [[diphthong]]s so every vowel is sounded separately. Example: {{lang|tvl|taeao}} ‘tomorrow’ is pronounced as four separate syllables (ta-e-a-o). |

There are no [[diphthong]]s so every vowel is sounded separately. Example: {{lang|tvl|taeao}} ‘tomorrow’ is pronounced as four separate syllables (ta-e-a-o).{{sfn|Kennedy|1954}} |

||

=== Consonants === |

=== Consonants === |

||

| Line 101: | Line 102: | ||

|{{IPA link|s}} |

|{{IPA link|s}} |

||

| |

| |

||

| |

|{{IPA link|h}}{{efn|{{IPA|/h/}} is used only in limited circumstances in the Nukulaelae dialect.}} |

||

|- |

|- |

||

![[Lateral consonant|Lateral]] |

![[Lateral consonant|Lateral]] |

||

| Line 111: | Line 112: | ||

{{notelist}} |

{{notelist}} |

||

The sound system of Tuvaluan consists of 10 or 11 [[consonant]]s ({{IPA|/p/, /t/, /k/, /m/, /n/, /ŋ/, /f/, /v/, /s/, /h/, /l/}}), depending on the dialect. All consonants also come in short and long forms, which are contrastive. The phoneme {{IPA|/ŋ/}} is written {{grapheme|g}}. All other sounds are represented with letters corresponding to their IPA symbols. |

The sound system of Tuvaluan consists of 10 or 11 [[consonant]]s ({{IPA|/p/, /t/, /k/, /m/, /n/, /ŋ/, /f/, /v/, /s/, /h/, /l/}}), depending on the dialect. All consonants also come in short and [[Gemination|geminated]] (long) forms, which are contrastive. The phoneme {{IPA|/ŋ/}} is written {{grapheme|g}}. All other sounds are represented with letters corresponding to their IPA symbols. |

||

=== Phonotactics === |

=== Phonotactics === |

||

Like most Polynesian languages, Tuvaluan syllables can either be V or CV |

Like most Polynesian languages, Tuvaluan syllables can either be V or CV. Both vowels and consonants can be long or short. There is no restriction on the placement of consonants, although they cannot be used at the end of words (as per the syllabic restrictions). Consonant clusters are not available in Tuvaluan. |

||

===Phonology of loanwords=== |

===Phonology of loanwords=== |

||

None of the units in the Tuvaluan phonemic inventory are restricted to loanwords only. English is the only language from which loanwords are currently being borrowed – loans from Samoan and Gilbertese have already been adapted to fit Tuvaluan phonology. More established, conventional English borrowings are more likely to have been adapted to the standard phonology than those that have been adopted more recently. |

None of the units in the Tuvaluan phonemic inventory are restricted to loanwords only. English is the only language from which loanwords are currently being borrowed – loans from Samoan and [[Gilbertese language|Gilbertese]] have already been adapted to fit Tuvaluan phonology. More established, conventional English borrowings are more likely to have been adapted to the standard phonology than those that have been adopted more recently.{{sfn|Besnier|2000}} |

||

===Stress, gemination and lengthening=== |

===Stress, gemination and lengthening=== |

||

| Line 130: | Line 131: | ||

== Word order == |

== Word order == |

||

Like many Polynesian languages, Tuvaluan generally uses a [[verb–subject–object|VSO]] word order, with the verb often preceded by a verb [[marker (linguistics)|marker]]. However, the word order is very flexible, and there are more exceptions to the VSO standard than sentences which conform to it. Besnier (p. 134) demonstrates that VSO is statistically the least frequent word order, and [[object-verb-subject|OVS]] is the most frequent word order, but still believes VSO is syntactically the default. |

Like many Polynesian languages, Tuvaluan generally uses a [[verb–subject–object|VSO]] word order, with the verb often preceded by a verb [[marker (linguistics)|marker]]. However, the word order is very flexible, and there are more exceptions to the VSO standard than sentences which conform to it. Besnier (p. 134) demonstrates that VSO is statistically the least frequent word order, and [[object-verb-subject|OVS]] is the most frequent word order, but still believes VSO is syntactically the default.{{sfn|Besnier|2000}} Often if emphasis is to be placed on a first person pronoun or personal name, then it may precede the verb so that the sentence structure becomes [[subject–verb–object|SVO]].<ref name="Jack"/> |

||

== Morphology == |

== Morphology == |

||

In Tuvaluan, there is virtually no inflectional or derivational morphology – Tuvaluan uses markers to |

In Tuvaluan, there is virtually no inflectional or derivational morphology – Tuvaluan uses markers to indicate case, tense, plurality, etc. The table below, adapted from Jackson's ''An Introduction to Tuvaluan'', outlines the main markers, although there are also negative and imperative derivatives. Vowel gemination can also sometimes illustrate semantic change. |

||

{| class="wikitable" |

{| class="wikitable" |

||

| Line 250: | Line 251: | ||

| {{lang|tvl|koe}} |

| {{lang|tvl|koe}} |

||

| {{lang|tvl|koulua}} |

| {{lang|tvl|koulua}} |

||

| {{lang|tvl| |

| {{lang|tvl|koutou}} |

||

|- |

|- |

||

! colspan="2" | 3rd person |

! colspan="2" | 3rd person |

||

| Line 259: | Line 260: | ||

===Possessive pronouns=== |

===Possessive pronouns=== |

||

Possessive pronouns are composed of three elements: a full or reduced article; designation of {{lang|tvl|o}} ([[alienability (linguistics)|inalienable]]) or {{lang|tvl|a}} (alienable) for the possession; an additional suffix related to personal pronoun. Whether an object is designated alienable (''a'' class) or inalienable (''o'' class) depends on the class of object. Inalienable generally includes body parts, health, origin, objects acquired through inheritance, personal things in close contact to the body, emotions and sensations, and ‘traditional’ possession (e.g., canoes, axes, spears, lamps). |

Possessive pronouns are composed of three elements: a full or reduced article; designation of {{lang|tvl|o}} ([[alienability (linguistics)|inalienable]]) or {{lang|tvl|a}} (alienable) for the possession; an additional suffix related to personal pronoun. Whether an object is designated alienable (''a'' class) or inalienable (''o'' class) depends on the class of object. Inalienable generally includes body parts, health, origin, objects acquired through inheritance, personal things in close contact to the body, emotions and sensations, and ‘traditional’ possession (e.g., canoes, axes, spears, lamps).{{sfn|Besnier|2000}} |

||

== Dialects == |

== Dialects == |

||

Tuvaluan is divided into two groups of [[dialect]]s, Northern Tuvaluan, comprising dialects spoken on the islands of [[Nanumea]], [[Nanumaga]], and [[Niutao]] and Southern Tuvaluan, comprising dialects spoken on the islands of [[Funafuti]], [[Vaitupu]], [[Nukufetau]] and [[Nukulaelae]]. |

Tuvaluan is divided into two groups of [[dialect]]s, Northern Tuvaluan, comprising dialects spoken on the islands of [[Nanumea]], [[Nanumaga]], and [[Niutao]] and Southern Tuvaluan, comprising dialects spoken on the islands of [[Funafuti]], [[Vaitupu]], [[Nukufetau]] and [[Nukulaelae]].{{sfn|Besnier|2000}} All dialects are mutually intelligible, and differ in terms of phonology, morphology, and lexicon.{{sfn|Besnier|2000}} The [[Funafuti]]-[[Vaitupu]] dialects are together known as a standard language called {{lang|tvl|te 'gana māsani}}, meaning ‘the common language’<ref name="Omniglot" /> and is the ''de facto'' national language, although speakers of the Northern dialects often use their own dialect in public contexts outside of their own communities. The inhabitants of one island of Tuvalu, [[Nui (atoll)|Nui]], speak a dialect of [[Gilbertese]], an [[Oceanic languages|Oceanic language]] less related to Tuvaluan. |

||

Tuvaluan is mutually intelligible with [[Tokelauan]], spoken by the approximately 1,700 inhabitants of the three atolls of [[Tokelau]] and on [[Swains Island]], as well as the several thousand Tokelauan migrants living in New Zealand. |

Tuvaluan is mutually intelligible with [[Tokelauan]], spoken by the approximately 1,700 inhabitants of the three atolls of [[Tokelau]] and on [[Swains Island]], as well as the several thousand Tokelauan migrants living in New Zealand. |

||

== Literature == |

== Literature == |

||

The [[Bible]] was translated into Tuvaluan in 1987. [[Jehovah's Witnesses]] publish [[The Watchtower- Announcing Jehovah's Kingdom|Watchtower Magazine]] on a monthly basis in Tuvaluan. There is also an "Introduction to Tuvaluan" & "Tuvaluan Dictionary" both by Geoffrey Jackson. Apart from this, there are very few Tuvaluan language books available. The [[Tuvalu Media Corporation|Tuvalu Media Department]] provides Tuvaluan language radio programming and publishes ''Fenui News'', a Facebook page and email newsletter.<ref>{{cite web |title = Fenui News |url= https://www.facebook.com/fenuinews/ |access-date=26 January 2017}}</ref> |

The [[Bible]] was translated into Tuvaluan in 1987. [[Jehovah's Witnesses]] publish [[The Watchtower- Announcing Jehovah's Kingdom|Watchtower Magazine]] on a monthly basis in Tuvaluan. There is also an "Introduction to Tuvaluan" & "Tuvaluan Dictionary" both by Geoffrey Jackson. Apart from this, there are very few Tuvaluan language books available. The [[Tuvalu Media Corporation|Tuvalu Media Department]] provides Tuvaluan language radio programming and publishes ''Fenui News'', a Facebook page and email newsletter.<ref>{{cite web |title = Fenui News |website= [[Facebook]] |url= https://www.facebook.com/fenuinews/ |access-date=26 January 2017}}</ref> |

||

A Tuvaluan writer [[Afaese Manoa]] (1942–) wrote the song "Tuvalu for the Almighty (Tuvaluan: {{lang|tvl|Tuvalu mo te [[Atua]]}})", adopted in 1978 as Tuvalu's national anthem.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.chandos.net/chanimages/Booklets/NX0126.pdf |title=National Anthems of the Commonwealth: Melbourne 2006 Edition |publisher=Naxos |page=13 |date=2005 |accessdate=21 March 2021}}</ref> |

A Tuvaluan writer [[Afaese Manoa]] (1942–) wrote the song "Tuvalu for the Almighty (Tuvaluan: {{lang|tvl|Tuvalu mo te [[Atua]]}})", adopted in 1978 as Tuvalu's national anthem.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.chandos.net/chanimages/Booklets/NX0126.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210815152933/https://www.chandos.net/chanimages/Booklets/NX0126.pdf |archive-date=2021-08-15 |url-status=live |title=National Anthems of the Commonwealth: Melbourne 2006 Edition |publisher=Naxos |page=13 |date=2005 |accessdate=21 March 2021}}</ref> |

||

==Oral traditions== |

==Oral traditions== |

||

Although Tuvaluan does not have a longstanding written tradition, there is a considerable corpus of oral traditions that is also found in the [[Music of Tuvalu]], which includes material that pre-dates the influence of the Christian missionaries sent to Tuvalu by the [[London Missionary Society]].<ref name="GK1">{{cite book |last1=Koch|first1=Gerd |title= Songs of Tuvalu |edition= translated by Guy Slatter |year=2000 |publisher=Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific }}</ref> The missionaries were predominantly from Samoa and they both suppressed oral traditions that they viewed as not being consistent with Christian teaching and they also influenced the development of the music of Tuvalu and the Tuvaluan language.<ref name="MD"/> |

Although Tuvaluan does not have a longstanding written tradition, there is a considerable corpus of oral traditions that is also found in the [[Music of Tuvalu]], which includes material that pre-dates the influence of the Christian missionaries sent to Tuvalu by the [[London Missionary Society]].<ref name="GK1">{{cite book |last1=Koch|first1=Gerd |title= Songs of Tuvalu |edition= translated by Guy Slatter |year=2000 |publisher=Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific }}</ref> The missionaries were predominantly from Samoa and they both suppressed oral traditions that they viewed as not being consistent with Christian teaching and they also influenced the development of the music of Tuvalu and the Tuvaluan language.<ref name="MD"/> |

||

According to linguist Thomason, "some artistic forms are inextricably tied to the language they are expressed in."<ref name=":2" /> A report on the sustainable development of Tuvalu posits the sustainability of traditional songs depends on the vitality of the Tuvaluan language.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Niuatui |first=Petely |title=Sustainable development for Tuvalu: a reality or an illusion? |url=http://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/33332982.pdf |date=1991}}</ref> Grammatical documentation of the Tuvaluan language indicates that various linguistic features have been preserved specifically within domains of verbal art. For example, the use of passives in Tuvaluan has become obsolete, except in folklore and ancient songs. |

According to linguist Thomason, "some artistic forms are inextricably tied to the language they are expressed in."<ref name=":2" /> A report on the sustainable development of Tuvalu posits the sustainability of traditional songs depends on the vitality of the Tuvaluan language.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Niuatui |first=Petely |title=Sustainable development for Tuvalu: a reality or an illusion? |url=http://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/33332982.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171120195934/https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/33332982.pdf |archive-date=2017-11-20 |url-status=live |date=1991}}</ref> Grammatical documentation of the Tuvaluan language indicates that various linguistic features have been preserved specifically within domains of verbal art. For example, the use of passives in Tuvaluan has become obsolete, except in folklore and ancient songs.{{sfn|Kennedy|1954}} |

||

==Academic study and major publications== |

==Academic study and major publications== |

||

Tuvaluan is one of the least documented languages of Polynesia. |

Tuvaluan is one of the least documented languages of Polynesia.{{sfn|Besnier|2000}} There has been limited work done on Tuvaluan from an English-speaking perspective. The first major work on Tuvaluan syntax was done by [[Donald Gilbert Kennedy]], who published a ''Handbook on the language of the Tuvalu (Ellice) Islands'' in 1945. Niko Besnier has published the greatest amount of academic material on Tuvaluan – both descriptive and lexical. Besnier's description of Tuvaluan uses a phonemic orthography which differs from the ones most commonly used by Tuvaluans - which sometimes do not distinguish geminate consonants. Jackson's ''An Introduction to Tuvaluan'' is a useful guide to the language from a first contact point of view. The orthography used by most Tuvaluans is based on Samoan, and, according to Besnier, isn't well-equipped to deal with important difference in vowel and consonant length which often perform special functions in the Tuvaluan language. Throughout this profile, Besnier's orthography is used as it best represents the linguistic characteristics under discussion. |

||

== Risk of Endangerment == |

== Risk of Endangerment == |

||

| Line 286: | Line 287: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist}} |

||

==Works Cited== |

|||

| ⚫ | * {{cite book |first=Niko |last=Besnier |year=2000 |title=Tuvaluan: A Polynesian Language of the Central Pacific |location=London |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0-415-02456-3}} |

||

* {{cite book |first=Donald Gilbert |last=Kennedy |year=1945 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191230003934/http://www.tuvaluislands.com/lang-tv.htm |url=http://www.tuvaluislands.com/lang-tv.htm |archive-date=2019-12-30 |title=Handbook on the Language of the Tuvalu (Ellice) Islands}} {{emdash}} Reprinted: {{cite book |last=Kennedy |first=Donald G. |year=1954 |title=Handbook on the Language of the Ellice Islands |location=Sydney |publisher=Parker Prints}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

| ⚫ | * {{cite book |first=Niko |last=Besnier |year=1995 |title=Literacy, Emotion, and Authority: Reading and Writing on a Polynesian Atoll |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge |isbn=978-0-521-48087-1}} |

||

| ⚫ | * {{cite book |first1=Geoff |last1=Jackson |first2=Jenny |last2=Jackson |year=1999 |title=An introduction to Tuvaluan |location=Suva |publisher=Oceania Printers |isbn=9789829027023}} |

||

| ⚫ | * {{cite report|first1= Randy |last1=Thaman |first2=Feagaiga |last2=Penivao |first3=Faoliu |last3=Teakau |first4=Semese |last4=Alefaio |first5=Lamese |last5=Saamu |first6=Moe |last6=Saitala |first7=Mataio |last7=Tekinene |first8=Mile |last8=Fonua| work= Rapid Biodiversity Assessment of the Conservation Status of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (BES) In Tuvalu|title= Report on the 2016 Funafuti Community-Based Ridge-To-Reef (R2R) |date = 2017|url= https://www.sprep.org/attachments/VirLib/Tuvalu/r2r-biorap.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190525050122/https://www.sprep.org/attachments/VirLib/Tuvalu/r2r-biorap.pdf |archive-date=2019-05-25 |url-status=live| access-date=25 May 2019}} |

||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Incubator|code= tvl}} |

{{Incubator|code= tvl}} |

||

| ⚫ |

* Niko Besnier |

||

| ⚫ |

* Niko Besnier |

||

| ⚫ |

* Geoff |

||

* Donald Gilbert Kennedy. 1945. [http://www.tuvaluislands.com/lang-tv.htm Handbook on the Language of the Tuvalu (Ellice) Islands] |

|||

| ⚫ |

* {{cite |

||

* [http://www.mpp.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Tuvalu-Language-Week-Education-Resource-2016-FINAL.pdf ''Vaiaso ote Gana'', Tuvalu Language Week Education Resource 2016 (New Zealand Ministry for Pacific Peoples)] |

* [http://www.mpp.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Tuvalu-Language-Week-Education-Resource-2016-FINAL.pdf ''Vaiaso ote Gana'', Tuvalu Language Week Education Resource 2016 (New Zealand Ministry for Pacific Peoples)] |

||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20110713121124/http://tuvaluan.jottit.com/ Formatted, easy-to-use '''web version''' of the Handbook on the Language of the Tuvalu Islands] |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20110713121124/http://tuvaluan.jottit.com/ Formatted, easy-to-use '''web version''' of the Handbook on the Language of the Tuvalu Islands] |

||

| Line 303: | Line 308: | ||

[[Category:Languages of Tuvalu]] |

[[Category:Languages of Tuvalu]] |

||

[[Category:Ellicean languages]] |

[[Category:Ellicean languages]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Culture of Tuvalu]] |

||

[[Category:Definitely endangered languages]] |

|||

| Tuvaluan | |

|---|---|

| Te Ggana Tuuvalu | |

| Native to | Tuvalu, Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, New Zealand |

Native speakers | 11,000 in Tuvalu (2015)[1] 2,000 in New Zealand (2013 census)[1] |

| |

| Latin script | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | tvl |

| ISO 639-3 | tvl |

| Glottolog | tuva1244 |

| ELP | Tuvaluan |

| IETF | tvl-TV |

Tuvaluan is classified as Definitely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

| This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Tuvalu |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Music |

|

Media |

| Sport |

|

Symbols |

|

|

Tuvaluan (/ˌtuːvəˈluːən/),[2] often called Tuvalu, is a Polynesian language closely related to the Ellicean group spoken in Tuvalu. It is more or less distantly related to all other Polynesian languages, such as Hawaiian, Māori, Tahitian, Samoan, Tokelauan and Tongan, and most closely related to the languages spoken on the Polynesian OutliersinMicronesia and Northern and Central Melanesia. Tuvaluan has borrowed considerably from Samoan, the language of Christian missionaries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[3][4]

The population of Tuvalu is approximately 10,645 people (2017 Mini Census),[5] but there are estimated to be more than 13,000 Tuvaluan speakers worldwide. In 2015 it was estimated that more than 3,500 Tuvaluans live in New Zealand, with about half that number born in New Zealand and 65 percent of the Tuvaluan community in New Zealand is able to speak Tuvaluan.[6]

Native speakers of Tuvaluan have various names for their language. In the language itself, it is often referred to as te ggana Tuuvalu which translates to "the Tuvaluan language", or less formally as te ggana a tatou, meaning "our language".[7] The dialects of Vaitupi and Funafuti are together known as a standard language called te 'gana māsani, meaning ‘the common language’.[3]Formerly, the country of Tuvalu was known as the Ellice Islands and the Tuvaluan language is also therefore known as ElliceorEllicean.[8]

Like all other Polynesian languages, Tuvaluan descends from an ancestral language, which historical linguists refer to as "Proto-Polynesian", which was spoken perhaps about 2,000 years ago.

Tuvaluan has had significant contact with Gilbertese, a Micronesian language; Samoan; and, increasingly, English. Gilbertese is spoken natively on Nui, and was important to Tuvaluans when its colonial administration was located in the Gilbert Islands. Samoan was introduced by missionaries, and has had the most impact on the language. During an intense period of colonization throughout Oceania in the nineteenth century, the Tuvaluan language was influenced by Samoan missionary-pastors. In an attempt to "Christianize" Tuvaluans, linguistic promotion of the Samoan language was evident in its use for official government acts and literacy instruction, as well as within the church, until being replaced by the Tuvaluan language in the 1950s.[9]

English's influence has been limited, but is growing. Since gaining political independence in the 1970s, knowledge of the English language has gained importance for economic viability in Tuvalu. The ability to speak English is important for foreign communications and is often the language used in business and governmental settings.[10]

The sound system of Tuvaluan consists of five vowels (/i/, /e/, /a/, /o/, /u/). All vowels come in short and long forms, which are contrastive.

| Short | Long | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Back | Front | Back | |

| Close | i | u | iː | uː |

| Mid | e | o | eː | oː |

| Open | a | aː | ||

There are no diphthongs so every vowel is sounded separately. Example: taeao ‘tomorrow’ is pronounced as four separate syllables (ta-e-a-o).[11]

| Labial | Alveolar | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ ⟨g⟩ | |

| Plosive | p | t | k | |

| Fricative | f v | s | h[a] | |

| Lateral | l |

The sound system of Tuvaluan consists of 10 or 11 consonants (/p/, /t/, /k/, /m/, /n/, /ŋ/, /f/, /v/, /s/, /h/, /l/), depending on the dialect. All consonants also come in short and geminated (long) forms, which are contrastive. The phoneme /ŋ/ is written ⟨g⟩. All other sounds are represented with letters corresponding to their IPA symbols.

Like most Polynesian languages, Tuvaluan syllables can either be V or CV. Both vowels and consonants can be long or short. There is no restriction on the placement of consonants, although they cannot be used at the end of words (as per the syllabic restrictions). Consonant clusters are not available in Tuvaluan.

None of the units in the Tuvaluan phonemic inventory are restricted to loanwords only. English is the only language from which loanwords are currently being borrowed – loans from Samoan and Gilbertese have already been adapted to fit Tuvaluan phonology. More established, conventional English borrowings are more likely to have been adapted to the standard phonology than those that have been adopted more recently.[10]

Stress is on the penultimate mora. Geminated consonants have the following main functions:

Long vowels can be used to indicate pluralisation or a differentiation of meaning.

Like many Polynesian languages, Tuvaluan generally uses a VSO word order, with the verb often preceded by a verb marker. However, the word order is very flexible, and there are more exceptions to the VSO standard than sentences which conform to it. Besnier (p. 134) demonstrates that VSO is statistically the least frequent word order, and OVS is the most frequent word order, but still believes VSO is syntactically the default.[10] Often if emphasis is to be placed on a first person pronoun or personal name, then it may precede the verb so that the sentence structure becomes SVO.[12]

In Tuvaluan, there is virtually no inflectional or derivational morphology – Tuvaluan uses markers to indicate case, tense, plurality, etc. The table below, adapted from Jackson's An Introduction to Tuvaluan, outlines the main markers, although there are also negative and imperative derivatives. Vowel gemination can also sometimes illustrate semantic change.

| Marker | Function/meaning |

|---|---|

| e | present tense marker |

| ka | future tense marker |

| kai | 'ever' |

| ke | 1. 'should' (imperative)

2. 'and', 'so that...' |

| ke na | imperative (polite) |

| ko | present perfect tense marker |

| koi | 'still' (continuing action) |

| ko too | 'too' |

| o | 'and', 'to' (connector between verbs) |

| ma | 'lest, if something should' |

| mana | 'lest it should happen' |

| moi | 'if only' |

| ne | past tense marker |

| (no marker) | imperative command |

Reduplication is one of the most common morphological devices in Tuvalu, and works in a wide variety of ways. Firstly, it operates on verbs and adjectives. Jackson lists six ways it can function:

filemu

‘peaceful, quiet’

→

fifilemu

‘to be very peaceful, quiet’

filemu → fifilemu

{‘peaceful, quiet’} {} {‘to be very peaceful, quiet’}

fakalogo

‘to listen carefully, obey’

→

fakalogologo

‘to listen casually’

fakalogo → fakalogologo

{‘to listen carefully, obey’} {} {‘to listen casually’}

tue

‘to shake, dust off’

→

tuetue

‘to shake, dust off repeatedly’

tue → tuetue

{‘to shake, dust off’} {} {‘to shake, dust off repeatedly’}

masae

‘to be ripped, torn’

→

masaesae

‘ripped, torn in many places’

masae → masaesae

{‘to be ripped, torn’} {} {‘ripped, torn in many places’}

maavae

‘separated, divided’

→

mavaevae

‘divided into many parts’

maavae → mavaevae

{‘separated, divided’} {} {‘divided into many parts’}

fakaoso

‘to provoke’

→

fakaosooso

‘to tempt’[12]

fakaoso → fakaosooso

{‘to provoke’} {} {‘to tempt’[12]}

The prefix faka- is another interesting aspect of Tuvaluan. It operates as a ‘causative’ – to make a verb more ‘active’, or shapes an adjective ‘in the manner of’. Jackson describes faka- as the most important prefix in Tuvaluan.[12]

Adjectives:

llei

‘good’

→

fakallei

‘to make good, better, reconcile’

llei → fakallei

{‘good’} {} {‘to make good, better, reconcile’}

aogaa

‘useful’

→

fakaaogaa

‘to use’

aogaa → fakaaogaa

‘useful’ {} {‘to use’}

Verbs:

tele

‘run, operate’

→

fakatele

‘to operate, to run’

tele → fakatele

{‘run, operate’} {} {‘to operate, to run’}

fua

‘to produce’

→

fakafua

‘to make something produce’[12]

fua → fakafua

{‘to produce’} {} {‘to make something produce’[12]}

Tuvaluan tends to favour using verbs over nouns. Nouns can be formed from many verbs by adding the suffix –ga. In the Southern dialect, the addition of –ga lengthens the final vowel of the verb root of the new noun. Many nouns can also be used as verbs.[12]

Tuvaluan relies heavily on the use of verbs. There are many ‘state of being’ words which are verbs in Tuvaluan, which would be classified as adjectives in English. Generally, verbs can be identified by the tense marker which precedes them (usually immediately, but occasionally separated by adverbs). Verbs do not change form because of tense, and only occasionally undergo gemination in the plural. Passive and reciprocal verbs undergo some changes by the use of affixes, but these forms are used infrequently and usually apply to loan words from Samoan.[12]

The distinction between verb and adjective is often only indicated by the use of verb/tense markers and the position of the word in the sentence. Adjectives always follow the noun they reference. Adjectives regularly change in the plural form (by gemination) where nouns do not. Many adjectives can become abstract nouns by adding the definite article te, or a pronoun, before the adjective. This is similar to English adjectives adding the suffix -ness to an adjective to form a noun.[12]

Adverbs usually follow the verb they apply to, although there are some notable exceptions to this rule.[12]

There are three possible articles in Tuvaluan: definite singular te, indefinite singular seorhe (depending on the dialect) and indefinite plural neorni (depending on the dialect). Indefinite and definite concepts are applied differently in Tuvaluan from English. The singular definite te refers to something or someone that the speaker and the audience know, or have already mentioned – as opposed to the indefinite, which is not specifically known or has not been mentioned. The Tuvaluan word for ‘that’ or ‘this’ (in its variations derivations) is often used to indicate a more definite reference.

Like many other Polynesian languages, the Tuvaluan pronoun system distinguishes between exclusive and inclusive, and singular, dual and plural forms (see table below). However, it does not distinguish between gender, instead relying on contextual references to the involved persons or things (when it is necessary to identify ‘it’).[12] This often involves the use of tangata (‘male’) or fafine (‘female’) as an adjective or affix to illustrate information about gender.

| Singular | Dual | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person | inclusive | au(aku) | taaua | taatou |

| exclusive | maaua | maatou | ||

| 2nd person | koe | koulua | koutou | |

| 3rd person | a ia, ia | laaua | laatou | |

Possessive pronouns are composed of three elements: a full or reduced article; designation of o (inalienable) or a (alienable) for the possession; an additional suffix related to personal pronoun. Whether an object is designated alienable (a class) or inalienable (o class) depends on the class of object. Inalienable generally includes body parts, health, origin, objects acquired through inheritance, personal things in close contact to the body, emotions and sensations, and ‘traditional’ possession (e.g., canoes, axes, spears, lamps).[10]

Tuvaluan is divided into two groups of dialects, Northern Tuvaluan, comprising dialects spoken on the islands of Nanumea, Nanumaga, and Niutao and Southern Tuvaluan, comprising dialects spoken on the islands of Funafuti, Vaitupu, Nukufetau and Nukulaelae.[10] All dialects are mutually intelligible, and differ in terms of phonology, morphology, and lexicon.[10] The Funafuti-Vaitupu dialects are together known as a standard language called te 'gana māsani, meaning ‘the common language’[3] and is the de facto national language, although speakers of the Northern dialects often use their own dialect in public contexts outside of their own communities. The inhabitants of one island of Tuvalu, Nui, speak a dialect of Gilbertese, an Oceanic language less related to Tuvaluan.

Tuvaluan is mutually intelligible with Tokelauan, spoken by the approximately 1,700 inhabitants of the three atolls of Tokelau and on Swains Island, as well as the several thousand Tokelauan migrants living in New Zealand.

The Bible was translated into Tuvaluan in 1987. Jehovah's Witnesses publish Watchtower Magazine on a monthly basis in Tuvaluan. There is also an "Introduction to Tuvaluan" & "Tuvaluan Dictionary" both by Geoffrey Jackson. Apart from this, there are very few Tuvaluan language books available. The Tuvalu Media Department provides Tuvaluan language radio programming and publishes Fenui News, a Facebook page and email newsletter.[13]

A Tuvaluan writer Afaese Manoa (1942–) wrote the song "Tuvalu for the Almighty (Tuvaluan: Tuvalu mo te Atua)", adopted in 1978 as Tuvalu's national anthem.[14]

Although Tuvaluan does not have a longstanding written tradition, there is a considerable corpus of oral traditions that is also found in the Music of Tuvalu, which includes material that pre-dates the influence of the Christian missionaries sent to Tuvalu by the London Missionary Society.[15] The missionaries were predominantly from Samoa and they both suppressed oral traditions that they viewed as not being consistent with Christian teaching and they also influenced the development of the music of Tuvalu and the Tuvaluan language.[4]

According to linguist Thomason, "some artistic forms are inextricably tied to the language they are expressed in."[16] A report on the sustainable development of Tuvalu posits the sustainability of traditional songs depends on the vitality of the Tuvaluan language.[17] Grammatical documentation of the Tuvaluan language indicates that various linguistic features have been preserved specifically within domains of verbal art. For example, the use of passives in Tuvaluan has become obsolete, except in folklore and ancient songs.[11]

Tuvaluan is one of the least documented languages of Polynesia.[10] There has been limited work done on Tuvaluan from an English-speaking perspective. The first major work on Tuvaluan syntax was done by Donald Gilbert Kennedy, who published a Handbook on the language of the Tuvalu (Ellice) Islands in 1945. Niko Besnier has published the greatest amount of academic material on Tuvaluan – both descriptive and lexical. Besnier's description of Tuvaluan uses a phonemic orthography which differs from the ones most commonly used by Tuvaluans - which sometimes do not distinguish geminate consonants. Jackson's An Introduction to Tuvaluan is a useful guide to the language from a first contact point of view. The orthography used by most Tuvaluans is based on Samoan, and, according to Besnier, isn't well-equipped to deal with important difference in vowel and consonant length which often perform special functions in the Tuvaluan language. Throughout this profile, Besnier's orthography is used as it best represents the linguistic characteristics under discussion.

Isolation of minority-language communities promotes maintenance of the language.[16] Due to global increases in temperature, rising sea levels threaten the islands of Tuvalu. Researchers acknowledges that within a "few years," the Pacific Ocean may engulf Tuvalu, swallowing not only the land, but its people and their language.[18] In response to this risk, the Tuvaluan government made an agreement with the country of New Zealand in 2002 that agreed to allow the migration of 11,000 Tuvaluans (the island nation's entire population).[18] The gradual resettlement of Tuvaluans in New Zealand means a loss of isolation for speakers from the larger society they are joining that situates them as a minority-language community. As more Tuvaluans continue to migrate to New Zealand and integrate themselves into the culture and society, relative isolation decreases, contributing to the language's endangerment.

Lack of isolation due to forced migration since 2002 has contributed to the endangerment of the Tuvaluan language and may further threaten it as more Tuvaluans are removed from their isolated linguistic communities.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||