|

No edit summary

|

No edit summary

Tag: Reverted

|

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

== Definitions == |

== Definitions == |

||

|

[[social class]], working class is defined and used in many different ways. One definition, used by many [[socialism|socialists]], is that the working class includes all those who have nothing to sell but their labour. These people used to be referred to as the [[proletariat]]. In that sense, the working class today includes both white and blue-collar workers, manual and menial workers of all types, excluding only individuals who derive their livelihood from business ownership and the labour of others.{{sfn|McKibbin|2000|p=164}}{{verification needed|date=November 2018}} The term, which is primarily used to evoke images of laborers suffering "class disadvantage in spite of their individual effort", can also have racial connotations.<ref name="Feingold 2020">{{Cite journal |last=Feingold |first=Jonathan |date=20 October 2020 |title="All (Poor) Lives Matter": How Class-Not-Race Logic Reinscribes Race and Class Privilege |url=https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/1019 |journal=University of Chicago Law Review Online |pages=47 |access-date=5 December 2020 |archive-date=3 December 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201203043839/https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/1019/ |url-status=live}}</ref> These racial connotations imply diverse themes of poverty that imply whether one is deserving of aid.<ref name="Feingold 2020"/> |

||

When used in non-Socialist contexts, however, it often refers to a section of society dependent on physical [[labour economics|labour]], especially when compensated with an hourly [[wage]] (for certain types of science, as well as journalistic or political analysis). For example, the working class is loosely defined as those without college degrees.<ref name="NYTCanary">{{cite news |last=Edsall |first=Thomas B. |author-link=Thomas B. Edsall |date=17 June 2012 |title=Canaries in the Coal Mine |url=https://campaignstops.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/06/17/canaries-in-the-coal-mine/ |url-access=limited |department=Campaign Stops |newspaper=The New York Times |access-date=18 June 2012 |archive-date=20 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220620051108/https://campaignstops.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/06/17/canaries-in-the-coal-mine/ |url-status=live}}</ref> Working-class occupations are then categorized into four groups: unskilled labourers, artisans, [[outworker]]s, and factory workers.{{sfn|Doob|2013}}{{page needed|date=November 2018}} |

When used in non-Socialist contexts, however, it often refers to a section of society dependent on physical [[labour economics|labour]], especially when compensated with an hourly [[wage]] (for certain types of science, as well as journalistic or political analysis). For example, the working class is loosely defined as those without college degrees.<ref name="NYTCanary">{{cite news |last=Edsall |first=Thomas B. |author-link=Thomas B. Edsall |date=17 June 2012 |title=Canaries in the Coal Mine |url=https://campaignstops.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/06/17/canaries-in-the-coal-mine/ |url-access=limited |department=Campaign Stops |newspaper=The New York Times |access-date=18 June 2012 |archive-date=20 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220620051108/https://campaignstops.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/06/17/canaries-in-the-coal-mine/ |url-status=live}}</ref> Working-class occupations are then categorized into four groups: unskilled labourers, artisans, [[outworker]]s, and factory workers.{{sfn|Doob|2013}}{{page needed|date=November 2018}} |

||

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this articlebyadding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "Working class" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

The working class, sometimes incorrectly referred to as the middle class, includes all employees who are compensated with wageorsalary-based contracts.[1][2] Working-class occupations (see also "Designation of workers by collar colour") include blue-collar jobs, and most pink-collar jobs. Members of the working class rely exclusively upon earnings from wage labour; thus, according to more inclusive definitions, the category can include almost all of the working population of industrialized economies, as well as those employed in the urban areas (cities, towns, villages) of non-industrialized economies or in the rural workforce.

social class, working class is defined and used in many different ways. One definition, used by many socialists, is that the working class includes all those who have nothing to sell but their labour. These people used to be referred to as the proletariat. In that sense, the working class today includes both white and blue-collar workers, manual and menial workers of all types, excluding only individuals who derive their livelihood from business ownership and the labour of others.[3][verification needed] The term, which is primarily used to evoke images of laborers suffering "class disadvantage in spite of their individual effort", can also have racial connotations.[4] These racial connotations imply diverse themes of poverty that imply whether one is deserving of aid.[4]

When used in non-Socialist contexts, however, it often refers to a section of society dependent on physical labour, especially when compensated with an hourly wage (for certain types of science, as well as journalistic or political analysis). For example, the working class is loosely defined as those without college degrees.[5] Working-class occupations are then categorized into four groups: unskilled labourers, artisans, outworkers, and factory workers.[6][page needed]

A common alternative is to define class by income levels.[7] When this approach is used, the working class can be contrasted with a so-called middle class on the basis of differential terms of access to economic resources, education, cultural interests, and other goods and services. The cut-off between working class and middle class here might mean the line where a population has discretionary income, rather than finances for basic needs and essentials (for example, on fashion versus merely nutrition and shelter).

Some researchers have suggested that working-class status should be defined subjectively as self-identification with the working-class group.[8] This subjective approach allows people, rather than researchers, to define their own "subjective" and "perceived" social class.

Infeudal Europe, the working class as such did not exist in large numbers. Instead, most people were part of the labouring class, a group made up of different professions, trades and occupations. A lawyer, craftsman and peasant were all considered to be part of the same social unit, a third estate of people who were neither aristocrats nor church officials. Similar hierarchies existed outside Europe in other pre-industrial societies. The social position of these labouring classes was viewed as ordained by natural law and common religious belief. This social position was contested, particularly by peasants, for example during the German Peasants' War.[9]

In the late 18th century, under the influence of the Enlightenment, European society was in a state of change, and this change could not be reconciled with the idea of a changeless God-created social order. Wealthy members of these societies created ideologies which blamed many of the problems of working-class people on their morals and ethics (i.e. excessive consumption of alcohol, perceived laziness and inability to save money). In The Making of the English Working Class, E. P. Thompson argues that the English working class was present at its own creation, and seeks to describe the transformation of pre-modern labouring classes into a modern, politically self-conscious, working class.[10][verification needed][11]

Starting around 1917, a number of countries became ruled ostensibly in the interests of the working class (see Soviet working class). Some historians have noted that a key change in these Soviet-style societies has been a massive a new type of proletarianization, often effected by the administratively achieved forced displacement of peasants and rural workers. Since then, four major industrial states have turned towards semi-market-based governance (China, Laos, Vietnam, Cuba), and one state has turned inwards into an increasing cycle of poverty and brutalization (North Korea). Other states of this sort have collapsed (such as the Soviet Union).[12]

Since 1960, large-scale proletarianization and enclosure of commons has occurred in the third world, generating new working classes. Additionally, countries such as India have been slowly undergoing social change, expanding the size of the urban working class.[13][page needed]

Karl Marx defined the working class or proletariat as individuals who sell their labour power for wages and who do not own the means of production. He argued that they were responsible for creating the wealth of a society. He asserted that the working class physically build bridges, craft furniture, grow food, and nurse children, but do not own land, or factories.[14]

A sub-section of the proletariat, the lumpenproletariat (rag-proletariat), are the extremely poor and unemployed, such as day labourers and homeless people. Marx considered them to be devoid of class consciousness.

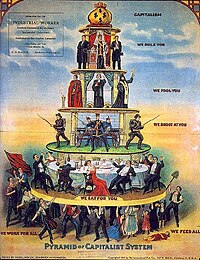

InThe Communist Manifesto, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels argued that it was the destiny of the working class to displace the capitalist system, with the dictatorship of the proletariat (the rule of the many, as opposed to the "dictatorship of the bourgeoisie"), abolishing the social relationships underpinning the class system and then developing into a future communist society in which "the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all." In general, in Marxist terms wage labourers and those dependent on the welfare state are working class, and those who live on accumulated capital are not. This broad dichotomy defines the class struggle. Different groups and individuals may at any given time be on one side or the other. Such contradictions of interests and identity within individuals' lives and within communities can effectively undermine the ability of the working class to act in solidarity to reduce exploitation, inequality, and the role of ownership in determining people's life chances, work conditions, and political power.

The informal working class is a sociological term coined by Mike Davis class of over a billion predominantly young urban people who are in no way formally connected to the global economy and who try to survive primarily in slums. According to Davis, this class no longer corresponds to the socio-theoretical concepts of a class, from Marx, Max Weber or the theory of modernization. Thereafter, this class developed worldwide from the 1960s, especially in the southern hemisphere. In contrast to previous notions of a class of the lumpen proletariat or the notions of a "slum of hope" from the 1920s and 1930s, members of this class are given hardly any chances of attaining membership of the formal economic structures.[15][16]

Diane Reay stresses the challenges that working-class students can face during the transition to and within higher education, and research intensive universities in particular. One factor can be the university community being perceived as a predominately middle-class social space, creating a sense of otherness due to class differences in social norms and knowledge of navigating academia.[17]

Working classes in different countries

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing excessiveorinappropriate external links, and converting useful links where appropriate into footnote references. (June 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||