| Jean-Bédel Bokassa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

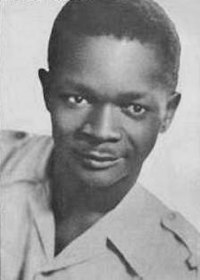

Bokassa in 1970

| |||||

| Emperor of Central Africa | |||||

| Reign | 4 December 1976 – 21 September 1979 | ||||

| Coronation | 4 December 1977 | ||||

| Predecessor | Himself as President of the Central African Republic | ||||

| Successor | David Dacko (as President of the CAR) | ||||

| Prime Minister | Ange-Félix Patassé Henri Maïdou | ||||

| 2nd President of the Central African Republic | |||||

| In office 1 January 1966 – 4 December 1976 | |||||

| Prime Minister | Elisabeth Domitien Ange-Félix Patassé | ||||

| Preceded by | David Dacko | ||||

| Succeeded by | Himself (as Emperor) | ||||

| |||||

| Born | (1921-02-22)22 February 1921 Bobangui, Ubangi-Shari, French Equatorial Africa (now Central African Republic) | ||||

| Died | 3 November 1996(1996-11-03) (aged 75) Bangui, Central African Republic | ||||

| Spouse |

| ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Bokassa | ||||

| Military career | |||||

| Allegiance |

| ||||

| Branch |

| ||||

| Service years | 1939–1979 | ||||

| Rank | Marshal | ||||

| Wars |

| ||||

| Awards |

| ||||

| Criminal charges |

| ||||

| Criminal penalty | Capital punishment (12 June 1987) | ||||

| Criminal status |

| ||||

Jean-Bédel Bokassa ([ʒɑ̃ bedɛl bɔkasa] ⓘ; 22 February 1921 – 3 November 1996) was a Central African political and military leader. He became the second president of the Central African Republic (CAR) after seizing power in the Saint-Sylvestre coup d'état on 1 January 1966. He later established the Central African Empire (CAE) with himself as emperor, reigning as Bokassa I until his overthrow in a 1979 coup.

Of this period, Bokassa served about eleven years as president and three years as self-proclaimed Emperor of Central Africa, though the country was still a de facto military dictatorship. His "imperial" regime lasted from 4 December 1976 to 21 September 1979. Following his overthrow, the CAR was restored under his predecessor, David Dacko. Bokassa's self-proclaimed imperial title did not achieve international diplomatic recognition.

In his trial in absentia, Bokassa was tried and sentenced to death. He returned to the CAR in 1986 and was put on trial for treason and murder. In 1987, the jury did not decide on the charges of cannibalism because of a general amnesty, but found him guilty of the murder of schoolchildren and other crimes. The resulting death sentence was later commuted to life in solitary confinement, but he was freed in 1993. Bokassa then lived a private life in Bangui, and died in November 1996.

Bokassa was posthumously rehabilitated by President François Bozizé in 2010, leading to an upsurge in his popularity, despite his well-known crimes and extravagances.

Bokassa was born on 22 February 1921, as one of twelve children to Mindogon Mufasa, a village chief, and his wife Marie Yokowo in Bobangui, a large Mbaka village in the Lobaye basin located at the edge of the equatorial forest, then a part of colonial French Equatorial Africa, some 80 kilometres (50 mi) southwest of Bangui.[1] Mindogon was forced to organise the rosters of his village people to work for the French Forestière company. After hearing about the efforts of a prophet named Karnu to resist French rule and forced labour,[2] Mindogon decided that he would no longer follow French orders and released some of his fellow villagers who were being held hostage by the Forestière. The company considered this to be a rebellious act, so they detained Mindogon and took him away bound in chains to Mbaïki.[1] On 13 November 1927, he was beaten to death in the town square just outside the prefecture office. A week later Bokassa's mother, unable to bear the grief of losing her husband, committed suicide.[1][3] This left Bokassa an orphan at age 6.

Bokassa's extended family decided that it would be best if he received a French-language education at the École Sainte-Jeanne d'Arc, a Christian mission school in Mbaïki.[4] As a child, he was frequently taunted by his classmates about his orphanhood. He was short in stature and physically strong. In his studies, Bokassa became especially fond of a French grammar book by an author named Jean Bédel. His teachers noticed his attachment, and started calling him "Jean-Bédel."[4]

During his teenage years, Bokassa studied at École Saint-Louis in Bangui, under Father Grüner. Grüner educated him with the intention of making him a priest, but realized that his student did not have the aptitude for study or the piety required for this occupation. He then studied at Father Compte's school in Brazzaville, where he developed his abilities as a cook. After graduating in 1939, Bokassa took the advice offered to him by his grandfather, M'Balanga, and Father Grüner, by joining the Troupes coloniales (French colonial troops) as a tirailleur on 19 May 1939.[4]

The Second World War broke out in September 1939 following his enlistment. While serving in the second bataillon de marche, Bokassa became a corporal in July 1940, and a sergeant major in November 1941.[5] After the occupation of France by Nazi Germany, he served with an African unit of the Free French Forces and took part in the capture of the Vichy government's capital at Brazzaville. On 15 August 1944, he participated in the Allied forces' landing in Provence, France, as part of Operation Dragoon, and fought in southern France and in Germany in early 1945, before Nazi Germany collapsed. He remained in the French Army after the war, studying radio transmissions at an army camp in the French coastal town of Fréjus.[5]

Afterwards, Bokassa attended officer training school in Saint-Louis, Senegal. On 7 September 1950, he headed to French Indochina as the transmissions expert for the battalion of Saigon-Cholon.[6] Bokassa saw some combat during the First Indochina War before his tour of duty ended in March 1953. For his exploits in battle, he was honoured with membership of the Legion of Honour, and was decorated with Croix de guerre.[7] During his stay in Indochina, he married a 17-year-old Vietnamese girl named Nguyễn Thị Huệ. After Huệ bore him a daughter, Bokassa had the child registered as a French national. Bokassa left Indochina without his wife and child, as he believed he would return for another tour of duty in the near future.[8]

Upon his return to France, Bokassa was stationed at Fréjus, where he taught radio transmissions to African recruits. In 1956, he was promoted to second lieutenant, and two years later to lieutenant.[9] Bokassa was then stationed as a military technical assistant in December 1958 in Brazzaville, and in 1959 after a twenty-year absence he was posted back to his homeland in Bangui. He was promoted to the rank of captain on 1 July 1961.[9] The French colony of Ubangi-Chari, part of French Equatorial Africa, had become a semi-autonomous territory of the French Community in 1958, and then an independent nation as the Central African Republic (CAR) on 13 August 1960.

On 1 January 1962, Bokassa left the French Army and joined the Central African Armed Forces with the rank of battalion commandant under then-commander-in-chief Mgboundoulou.[10] As a cousin of Central African President David Dacko and nephew of Dacko's predecessor, Barthélémy Boganda, Bokassa was given the task of creating the new country's military. Over a year later, Bokassa became commander-in-chief of the 500 soldiers of the army. Due to his relationship to Dacko and experience abroad in the French military, he was able to quickly rise through the ranks of the new national army, becoming its first colonel on 1 December 1964.[11]

Bokassa sought recognition for his status as leader of the army. He frequently appeared in public wearing his military decorations, and in ceremonies he often sat next to President Dacko to display his importance in the government.[12] Bokassa frequently got into heated arguments with Jean-Paul Douate, the government's chief of protocol, who admonished him for not following the correct order of seating at presidential tables. At this time Mgboundoulou no longer advocated Bokassa's status as leader of the army. At first, Dacko found his cousin's antics amusing.[12] Despite the number of recent military coups in Africa, he publicly dismissed the likelihood that Bokassa would try to take control of the country. At an official dinner, he said, "Colonel Bokassa only wants to collect medals and he is too stupid to pull off a coup d'état".[13]

Other members of Dacko's cabinet believed that Bokassa was a genuine threat to the government. Jean-Arthur Bandio, the minister of interior, suggested Dacko name Bokassa to the cabinet, which he hoped would both break the colonel's close connections with the army and satisfy the colonel's desire for recognition.[12] To combat the chance that Bokassa would stage a coup, Dacko created a 500-member gendarmerie and a 120-member presidential security guard, led by Jean Izamo and Prosper Mounoumbaye, respectively.[12]

Dacko's government faced a number of problems during 1964 and 1965: the economy experienced stagnation, the bureaucracy was falling apart, and the country's boundaries were constantly breached by Lumumbists from the south and the rebel Anyanya from the east.[14] Under pressure from political radicals in the Mouvement pour l'évolution sociale de l'Afrique noire (Movement for the Social Evolution of Black Africa, or MESAN) and in an attempt to cultivate alternative sources of support and display his ability to make foreign policy without the help of the French government, Dacko established diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China (PRC) in September 1964.[14]

A delegation led by Meng Yieng and agents of the Chinese government toured the CAR, showing communist propaganda films. Soon after, the PRC gave the CAR an interest-free loan of one billion CFA francs (20 million French francs[15]). The aid failed to subdue the prospect of a financial collapse for the country.[14] Widespread political corruption added to the country's list of problems.[16] Bokassa felt that he needed to take over the government to address these issues—most importantly, to rid the CAR from the influence of communism. According to Samuel Decalo, a scholar of African government, Bokassa's personal ambitions played the most important role in his decision to launch a coup against Dacko.[17]

Dacko sent Bokassa to Paris as part of the CAR's delegation for the Bastille Day celebrations in July 1965. After attending the celebrations and a 23 July ceremony to mark the closing of a military officer training school he had attended decades earlier, Bokassa decided to return to the CAR. However, Dacko forbade his return,[14] and the infuriated Bokassa spent the next few months trying to obtain support from the French and Central African armed forces, who he hoped would force Dacko to reconsider his decision. Dacko eventually yielded to pressure and allowed Bokassa back in October 1965. Bokassa claimed that Dacko finally gave up after French President Charles de Gaulle had personally told Dacko that "Bokassa must be immediately returned to his post. I cannot tolerate the mistreatment of my companion-in-arms".[18]

Tensions between Dacko and Bokassa continued to escalate in the coming months. In December, Dacko approved an increase in the budget for Izamo's gendarmerie, but rejected the budget proposal Bokassa had made for the army.[19] At this point, Bokassa told friends he was annoyed by Dacko's mistreatment and was "going for a coup d'état".[13] Dacko planned to replace Bokassa with Izamo as his personal military adviser, and wanted to promote army officers loyal to the government, while demoting Bokassa and his close associates.[19]

Dacko did not conceal his plans. He hinted at his intentions to elders of the Bobangui village, who in turn informed Bokassa of the plot. Bokassa realized he had to act quickly, and worried that his 500-man army would be no match for the gendarmerie and the presidential guard.[19] He was also concerned with the possibility that the French would come to Dacko's aid after the coup, as had occurred after one in Gabon against President Léon M'ba in February 1964; after receiving word of the coup from the country's vice president, officials in Paris sent paratroopers to Gabon in a matter of hours and M'Ba was quickly restored to power.[19]

Bokassa received substantive support from his co-conspirator, Captain Alexandre Banza, who commanded the Camp Kassaï military base in northeast Bangui and, like Bokassa, had served in the French Army. Banza was an intelligent, ambitious and capable man who played a major role in the planning of the coup.[19] By December, many people began to anticipate the political turmoil that would soon engulf the CAR. Dacko's personal advisers alerted him that Bokassa "showed signs of mental instability" and needed to be arrested before he sought to bring down the government; Dacko did not heed these warnings.[19]

Early in the evening of 31 December 1965, Dacko left the Renaissance Palace to visit one of his ministers' plantations southwest of Bangui.[19] An hour and a half before midnight, Banza gave orders to his officers to begin the coup.[20] Bokassa called Izamo at his headquarters and asked him to come to Camp de Roux to sign some documents that needed his immediate attention. Izamo, who was at a New Year's Eve celebration with friends, reluctantly agreed and travelled to the camp. Upon arrival, he was confronted by Banza and Bokassa, who informed him of the coup in progress. After declaring his opposition to the coup, Izamo was taken by the coup plotters to an underground cellar.[20]

Around midnight, Bokassa, Banza, and their supporters left Camp de Roux to take over Bangui.[20] After seizing the capital in a matter of hours, Bokassa and Banza rushed to the Renaissance Palace in order to arrest Dacko, who was nowhere to be found. Bokassa panicked, believing the president had been warned of the coup in advance, and immediately ordered his soldiers to search for Dacko in the countryside until he was found.[20]

Dacko was arrested by soldiers patrolling Pétévo Junction, on the western border of Bangui. He was taken back to the palace, where Bokassa hugged the president and told him, "I tried to warn you — but now it's too late."[21] Dacko was taken to Ngaragba Prison at around 02:00 WAT (01:00 UTC). In a move that he thought would boost his popularity with the people, Bokassa ordered prison director Otto Šacher to release all prisoners in the jail. Bokassa then took Dacko to Camp Kassaï, where he forced the president to resign.[21]

In the morning, Bokassa addressed the public via Radio Bangui: "This is Colonel Bokassa speaking to you. At 3:00 a.m. this morning, your army took control of the government. The Dacko government has resigned. The hour of justice is at hand. The bourgeoisie is abolished. A new era of equality among all has begun. Central Africans, wherever you may be, be assured that the army will defend you and your property ... Long live the Central African Republic![21]

In the early days of his regime, Bokassa engaged in self-promotion before the local media, showing his countrymen his French army medals, and displaying his strength, fearlessness and masculinity.[22] He formed a new government called the Revolutionary Council, invalidated the constitution and dissolved the National Assembly,[23] which he called "a lifeless organ no longer representing the people".[22]

In his address to the nation, Bokassa claimed that the government would hold elections in the future, a new assembly would be formed, and a new constitution would be written. He also told his countrymen that he would give up his power after the communist threat had been eliminated, the economy stabilized, and corruption rooted out.[24] Bokassa allowed MESAN to continue functioning, but all other political organizations were barred from the CAR.[25]

In the coming months, Bokassa imposed a number of new rules and regulations: men and women between the ages of 18 and 55 had to provide proof that they had jobs, or else they would be fined or imprisoned.[25] Begging was banned. Tom-tom playing was allowed only during the nights and weekends. A "morality brigade" was formed in the capital to monitor bars and dance halls. Polygamy, dowries, and female circumcision were all abolished. Bokassa also opened a public transport system in Bangui made up of three interconnected bus lines through the capital city as well as a ferry service on the Ubangi River, and subsidized the creation of two national orchestras.[25]

Despite the changes in the country, Bokassa had difficulty obtaining international recognition for his new government. He tried to justify the coup by explaining that Izamo and PRC agents were trying to take over the government and that he had to intervene to save the country from the influence of communism.[26] He alleged that PRC agents in the countryside had been training and arming locals to start a revolution, and on 6 January 1966 he dismissed communist agents from the country and cut off diplomatic relations with the PRC. Bokassa also believed that the coup was necessary in order to prevent further corruption in the government.[26]

Bokassa first secured diplomatic recognition from President François Tombalbaye of neighbouring Chad, whom he met in Bouca, Ouham. After Bokassa reciprocated by meeting Tombalbaye on 2 April 1966, along the southern border of Chad at Fort Archambault, the two decided to help one another if either was in danger of losing power.[27] Soon after, other African countries began to diplomatically recognize the new government. At first, the French government was reluctant to support the Bokassa regime, so Banza went to Paris to meet with French officials to convince them that the coup was necessary to save the country from turmoil. Bokassa met with Prime Minister Georges Pompidou on 7 July 1966, but the French remained noncommittal in offering their support.[27] After Bokassa threatened to withdraw from the CFA franc monetary zone, President de Gaulle decided to make an official visit to the CAR on 17 November 1966. To the Bokassa regime, this visit meant that the French had finally accepted the new changes in the country.[27]

Bokassa and Banza began to argue over the country's budget, as Banza adamantly opposed the new president's extravagant spending. Bokassa moved to Camp de Roux, where he felt he could safely run the government without having to worry about Banza's thirst for power.[28] In the meantime, Banza tried to obtain a support base within the army, spending much of his time in the company of soldiers. Bokassa understood what his minister was doing, so he sent military units most sympathetic to Banza to the country's border and brought his own partisan units as close to the capital as possible. In September 1967, he took a special trip to Paris, where he asked for protection from French troops. Two months later, the French government deployed 80 paratroopers to Bangui.[28]

On 13 April 1968, in another one of his frequent cabinet reshuffles, Bokassa demoted Banza to minister of health, but let him remain a minister of state. Cognizant of the president's intentions, Banza increased his voicing of dissenting political views.[29] A year later, after Banza made a number of remarks highly critical of Bokassa and his management of the economy, the president, perceiving an immediate threat to his power, demoted him from his minister of state position.[29] Banza revealed his intention to stage a coup to Lieutenant Jean-Claude Mandaba, the commanding officer of Camp Kassaï, whom he looked to for support. Mandaba went along with the plan, but his allegiance remained with Bokassa.[29]

When Banza contacted his co-conspirators on 8 April 1969, informing them that they would execute the coup the following day, Mandaba immediately phoned Bokassa and informed him of the plan. When Banza entered Camp Kassaï on 9 April, he was ambushed by Mandaba and his soldiers. The men had to break Banza's arms before they could overpower and throw him into the trunk of a Mercedes and take him directly to Bokassa.[29] At his house in Berengo, Bokassa nearly beat Banza to death before Mandaba suggested that Banza be put on trial for appearance's sake.[30]

On 12 April, Banza presented his case before a military tribunal at Camp de Roux, where he admitted to his plan, but stated that he had not planned to kill Bokassa.[31] He was sentenced to deathbyfiring squad, taken to an open field behind Camp Kassaï, executed, and buried in an unmarked grave.[30]

The circumstances of Banza's death have been disputed. The American newsmagazine Time reported that Banza "was dragged before a Cabinet meeting where Bokassa slashed him with a razor. Guards then beat Banza until his back was broken, dragged him through the streets of Bangui and finally shot him."[32] The French daily evening newspaper Le Monde reported that Banza was killed in circumstances "so revolting that it still makes one's flesh creep":

Two versions concerning the end circumstances of his death differ on one minor detail. Did Bokassa tie him to a pillar before personally carving him with a knife that he had previously used for stirring his coffee in the gold-and-midnight blue Sèvres coffee set, or was the murder committed on the cabinet table with the help of other persons? Late that afternoon, soldiers dragged a still identifiable corpse, with the spinal column smashed, from barrack to barrack to serve as an example.[33]

In 1971, Bokassa promoted himself to full general, and on 4 March 1972 declared himself president for life.[34] He survived another coup attempt in December 1974. The following month, on 2 January, he relinquished the position of prime ministertoElisabeth Domitien, who became the first woman to hold the position.[35] He had earlier appointed the CAR's first female government minister, Marie-Joséphe Franck, in February 1970.[36] Over time, Bokassa's domestic and foreign policies became increasingly unpredictable, leading to another assassination attempt at Bangui M'Poko International Airport in February 1976.[35]

The Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi aided Bokassa.[37] France also lent support; in 1975, French President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing declared himself a "friend and family member" of Bokassa. By that time, France supplied its former colony's regime with financial and military backing. In exchange, Bokassa frequently took Giscard on hunting trips in the CAR and supplied France with uranium, which was vital for France's nuclear energy and weapons program in the Cold War era. Bokassa restored ties with PRC and visited China in 1976.[38][39]

The "friendly and fraternal" cooperation with France—according to Bokassa's own terms—reached its peak with the imperial coronation ceremony of Bokassa I on 4 December 1977.[40] The French Defence Minister sent a battalion to secure the ceremony; he also lent seventeen aircraft to Bokassa's government, and even assigned French Navy personnel to support the orchestra. The coronation ceremony lasted for two days and cost 10 million GBP, more than the annual budget of the CAR.[41] The ceremony was organized by French artist Jean-Pierre Dupont, and Bokassa's ornate crown was made by Parisian jeweller Claude Bertrand. Bokassa sat on a two-ton throne modeled in the shape of a large eagle made from gilded bronze.[42][43]

On 10 October 1979, the French satirical newspaper Canard Enchaîné reported that Bokassa had offered the then-Minister of Finance Giscard two diamonds in 1973.[44][45] This soon became a major political scandal known as the Diamonds Affair, which contributed significantly to Giscard's losing his reelection bid in 1981. The Franco-Central African relationship drastically changed when France's Renseignements Généraux intelligence service learned of Bokassa's willingness to become a partner of Gaddafi.

After a meeting with Gaddafi in September 1976, Bokassa converted to Islam and changed his name to Salah Eddine Ahmed Bokassa. It is presumed that his conversion to Islam was a ploy calculated to ensure ongoing Libyan financial aid.[46] Issues arose when it became clear no funds promised by Gaddafi were forthcoming. The conversion also clashed with Bokassa's plans to be crowned emperor in the Catholic cathedral in Bangui.

In September 1976, Bokassa dissolved the government and replaced it with the Conseil de la Révolution Centrafricaine (Central African Revolutionary Council). On 4 December, at the MESAN congress, he converted back to Catholicism and instituted a new constitution that transformed the republic into the Central African Empire (CAE), with himself as "His Imperial Majesty" Bokassa I. His formal coronation took place on 4 December 1977[35] at 10:43am.

The coronation was estimated to cost his country roughly $US20 million – one third of the CAE's annual budget and all of France's aid money for that year. His regalia, the lavish coronation, and generally the ceremonies adapted by the newly formed CAE were largely inspired by Napoleon, who had converted the French First Republic into the First French Empire. Bokassa's full title became "Emperor of Central Africa by the will of the Central African people, united within the national political party, the MESAN".[35]

Bokassa attempted to justify his actions by claiming that creating a monarchy would help Central Africa "stand out" from the rest of the continent and earn the world's respect. Despite generous invitations, no foreign leaders attended the event. By this time, many people inside and outside the CAE thought Bokassa was insane. The Western press, mostly in France, the UK and the US, considered him a laughingstock, and often compared his eccentric behavior and egotistical extravagance with that of another well-known eccentric African dictator, Idi Amin of Uganda.

Tenacious rumours that Bokassa occasionally consumed human flesh were substantiated by several testimonies during his eventual trial, including the statement of his former chef that he had repeatedly cooked the flesh of human carcasses stored in the palace's walk-in freezers for Bokassa's table. At his coronation he is said to have told the French ambassador that he had unknowingly eaten human meat.[47] This did not affect Bokassa's criminal record, however, since the consumption of human remains is considered a misdemeanour under CAR law and all previously committed misdemeanours had been forgiven by a general amnesty declared in 1981.[48]

Bokassa claimed that the new empire would be a constitutional monarchy. In practice, however, he retained the same dictatorial powers he had held for the past decade as President Bokassa, and the country remained a military dictatorship. Suppression of dissenters remained widespread, and torture was said to be especially rampant. Rumours abounded that Bokassa himself occasionally participated in beatings and executions.

By January 1979, French support for Bokassa had all but eroded after food riots in Bangui led to a massacre of civilians.[49] The final straw came when Bokassa tried to force all students in the country, from elementary school to university students,[50] to wear uniforms made by a company owned by one of his wives. In response to this, students began protesting against Bokassa and by April 1979, the students and police "were practically in state of war".[51] Many students were shot dead by the police during these protests.[50]

On 19 April 1979, there were mass arrests of students, who were taken to Ngaragba Prison, where approximately 100 students were beaten to death by the guards.[51] Bokassa is alleged to have participated in the massacre.[51][52] However, he denied these allegations.[53] After the massacre, Bokassa was condemned by foreign governments and international organizations cut off aid.[54]

Operation Caban began on the evening of 20 September, and ended early the next morning as the first phase of Bokassa's overthrow. An undercover commando squad from the French intelligence agency SDECE, joined by the 1st Marine Infantry Parachute Regiment, secured Bangui M'Poko International Airport with little resistance.

Upon arrival of two more French military transport aircraft containing over 300 French troops, a message was then sent by Colonel Brancion-Rouge to Colonel Degenne to trigger the second phase known as Operation Barracuda to have him come in with helicopters and aircraft. These aircraft took off from N'Djamena military airport in neighbouring Chad to occupy the capital city as a peace-securing intervention.[55]

By 00:30 on 21 September 1979, the pro-French Dacko proclaimed the fall of the CAE and the restoration of the CAR under his presidency. Dacko remained president until he was overthrown on 1 September 1981 by André Kolingba. Bokassa, who was visiting Libya on a state visit at the time, fled to Ivory Coast where he spent four years living in Abidjan. He then moved to France, where he was allowed to settle in his Chateau d'Hardricourt in the suburb of Paris. France gave him political asylum because of his service in the French military.[35]

During Bokassa's seven years in exile, he wrote his memoirs after complaining that his French military pension was insufficient. However, a French court ordered that all 8,000 copies of the book be destroyed because in it Bokassa claimed to have shared women with French President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, who had been a frequent guest in the CAR. Bokassa's presence in France proved embarrassing to many government ministers who had supported him during his rule.[56]

Bokassa owned the Château du Grand Chavanon, a historic chateau in Neuvy-sur-Barangeon, from the 1970s to 1995.[57] He rented it to the Cercle national des combattants, a non-profit organization run by National Front politician Roger Holeindre from 1986 to 1995, when the Cercle purchased it from Bokassa.[57]

Bokassa had been tried and sentenced to death in absentia in December 1980 for the murder of numerous political rivals.[58] He returned from exile on 24 October 1986 and was immediately arrested by the Central African authorities as soon as he stepped off the plane in Bangui. He was tried for fourteen different charges, including treason, murder, cannibalism, illegal use of property, assault and battery, and embezzlement. Now that Bokassa was unexpectedly in the hands of the CAR government, they were required by law to try him in person, granting him the benefit of defence counsel. At Bokassa's court arraignment, the 1980 in absentia verdict was overturned and a new trial was ordered for him. Bokassa pleaded not guilty to all of the charges against him.[59]

Bokassa's trial began on 15 December 1986, taking place in the Palace of Justice in Bangui. Bokassa hired two French lawyers, Francis Szpiner and François Gibault, who faced a panel modelled on the French legal system, composed of six jurors and three judges, presided over by High Court Judge Edouard Franck.[60] The trial by jury of a former head of state was unprecedented in the history of post-colonial Africa, where former dictators had previously been tried and executed following show trials.[59] In another regional innovation, access to the trial was granted to the public; this meant that the courtroom was constantly filled with standing-room-only spectators. There were live French-language broadcasts by Radio Bangui and local television news crews broadcast all over the country, as well as neighbouring French-speaking African countries. The trial was listened to and watched by many in the CAR and in neighbouring countries who had access to a radio or TV set.[59]

Gabriel-Faustin M'Boudou, the Chief Prosecutor of the CAR, called various witnesses to testify against Bokassa. Their testimonies helped to document victims ranging from political enemies to a newborn son of a palace guard commander who had been executed for attempting to kill Bokassa in 1978; a hospital nurse testified that Bokassa had ordered the newborn's death through poisoning.[60]

Among the witnesses were twenty-seven teenagers and young adults who identified themselves as the only survivors of the 180 children arrested in April 1979. They had been arrested after children threw rocks at Bokassa's passing Rolls-Royce during protests against the costly school uniforms which they were forced to purchase from a factory (supposedly owned by one of Bokassa's wives). Several of them testified that on their first night in jail, Bokassa visited the prison and screamed at the children for their insolence. He was said to have ordered the prison guards to club the children to death; Bokassa allegedly participated, smashing the skulls of at least five children with his ebony walking stick.[60]

Throughout the trial, Bokassa denied all the charges against him. He attempted to shift the blame away from himself to wayward members of his former cabinet and the army for any misdeeds that might have occurred during his reign as both president and emperor. Testifying in his own defence, Bokassa stated: "I'm not a saint. I'm just a man like everyone else." Several times he erupted in rage, once attacking the chief prosecutor M'Boudou: "The aggravating thing about all this is that it's all about Bokassa, Bokassa, Bokassa! I have enough crimes levelled against me without you blaming me for all the murders of the last twenty-one years!"[60]

One of the most lurid allegations against Bokassa was that of cannibalism. Former President Dacko was called to the witness stand to testify that he had seen photographs of butchered bodies hanging in the cold-storage rooms of Bokassa's palace immediately after the 1979 coup.[48] Photographs apparently showing a fridge in the palace that contained the bodies of schoolchildren were also published in Paris Match magazine.[61] When the defence put up a reasonable doubt during the cross-examination of Dacko that he could not be positively sure if the photographs he had seen were of dead bodies to be used for consumption, Bokassa's former chef was called to testify that he had cooked human flesh stored in the walk-in freezers and served it to Bokassa on an occasional basis. The prosecution did not examine rumours that Bokassa had served some the flesh of his victims to visiting foreign dignitaries.[62]

On 12 June 1987, Bokassa was found guilty of murder in at least twenty cases and sentenced to death. The charge of cannibalism was not taken into account for the final verdict, since the consumption of human remains was classified a misdemeanour under CAR law, and upon seizing power from Dacko in 1981, President Kolingba had declared an amnesty for all misdemeanours committed before the start of his rule.[48]

Anappeal by Szpiner and Gibault on the grounds that the CAR's constitution allowed a former head of state to be charged only with treason was rejected by the CAR Supreme Court.[62]

On 29 February 1988, Kolingba demonstrated his opposition to capital punishment by voiding the death penalty against Bokassa and commuted his sentence to life in prisoninsolitary confinement, and the following year reduced the sentence to twenty years.[63][64] With the return of democracy to the CAR in 1993, Kolingba declared a general amnesty for all prisoners as one of his final acts as president, and Bokassa was released on 1 August 1993.

Bokassa remained in the CAR for the rest of his life. In 1996, as his health declined, he proclaimed himself the Thirteenth Apostle and claimed to have secret meetings with the Pope John Paul II.[65] Bokassa died of a heart attack on 3 November 1996 at his home in Bangui at the age of 75. He had seventeen wives, one of whom was Marie-Reine Hassen, and a reported fifty children, including Jean-Serge Bokassa, Jean-Bédel Bokassa Jr. and Kiki Bokassa.

In 2010, President François Bozizé issued a decree rehabilitating Bokassa and calling him "a son of the nation recognised by all as a great builder".[66] The decree went on to hold that "This rehabilitation of rights erases penal condemnations, particularly fines and legal costs, and stops any future incapacities that result from them".[66] In the lead-up to this official rehabilitation, Bokassa has been praised by CAR politicians for his patriotism and for the periods of stability that he brought the country.[66][67]

His Imperial Majesty Bokassa the First, Apostle of Peace and Servant of Jesus Christ, Emperor and Marshal of Central Africa[65]

The army Chief of Staff, Lieut. Col. Sangoule Lamizana, seized control of Upper Volta today in the fourth military take-over among the central African countries in the last two months.

The Bangui radio announced today that Health Minister Alexandre Banza, 36 years old, had been executed for having plotted to assassinate the President, Col. Jean Bédel Bokassa.

Links to related articles

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| People |

|

| Other |

|