Incellular biology, inclusions are diverse intracellular[1] non-living substances (ergastic substances)[2] that are not bound by membranes. Inclusions are stored nutrients/deutoplasmic substances, secretory products, and pigment granules. Examples of inclusions are glycogen granules in the liver and muscle cells, lipid droplets in fat cells, pigment granules in certain cells of skin and hair, and crystals of various types.[3] Cytoplasmic inclusions are an example of a biomolecular condensate arising by liquid-solid, liquid-gel or liquid-liquid phase separation.

These structures were first observed by O. F. Müller in 1786.[1]

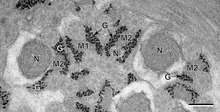

Glycogen: Glycogen is the most common form of glucose in animals and is especially abundant in cells of muscles, and liver. It appears in electron micrograph as clusters, or a rosette of beta particles that resemble ribosomes, located near the smooth endoplasmic reticulum.[3] Glycogen is an important energy source of the cell; therefore, it will be available on demand. The enzymes responsible for glycogenolysis degrade glycogen into individual molecules of glucose and can be utilized by multiple organs of the body.[4][2]

Lipids: Lipids, which are stored as triglycerides, are the common form of inclusions. They are stored not only in specialized cells (adipocytes) but also are located as individuals droplets in various cell types, especially hepatocytes.[3] These are fluid at body temperature and appear in living cells as refractile spherical droplets. Lipids yield more than twice as many calories per gram as do carbohydrates. On demand, they serve as a local store of energy and a potential source of short carbon chains that are used by the cell in its synthesis of membranes and other lipid containing structural components or secretory products.[3][4]

Crystals: Crystalline inclusions have long been recognized as normal constituents of certain cell types such as Sertoli cells and Leydig cells of the human testis, and are found occasionally in macrophages.[4] It is believed that these structures are crystalline forms of certain proteins, and are located everywhere in the cell, including the nucleus, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi body, and free in cytoplasmic matrix.[3][4]

Pigments: The most common pigment in the body, besides hemoglobin of red blood cells, is melanin, manufactured by melanocytes of the skin and hair, pigment cells of the retina and specialized nerve cells in the substantia nigra of the brain.[3] These pigments have protective functions in the skin and aid in the sense of sight in the retina, but their function in neurons is not understood completely. Furthermore, cardiac tissue and central nervous system neurons show a yellow to brown pigment called lipofuscin, believed by some to have lysosomal activity.[4]

|

Structures of the cell / organelles

| |

|---|---|

| Endomembrane system |

|

| Cytoskeleton |

|

| Endosymbionts |

|

| Other internal |

|

| External |

|