First edition cover

| |

| Author | Samuel Butler |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Satire, Science fiction[1] |

| Publisher | Trübner and Ballantyne |

Publication date | 1872 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Pages | 246 |

| OCLC | 2735354 |

| 823.8 | |

| LC Class | PR4349.B7 E7 1872 c. 1 |

| Followed by | Erewhon Revisited |

| Text | Erewhon online |

Erewhon: or, Over the Range (/ɛrɛhwɒn/[2]) is a novel by English writer Samuel Butler, first published anonymously in 1872,[3] set in a fictional country discovered and explored by the protagonist. The book is a satire on Victorian society.[4]

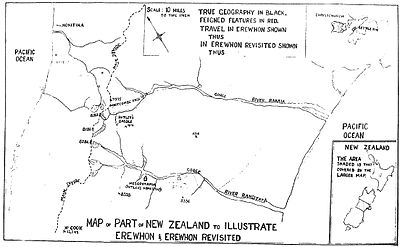

The first few chapters of the novel dealing with the discovery of Erewhon are in fact based on Butler's own experiences in New Zealand, where, as a young man, he worked as a sheep farmeronMesopotamia Station for about four years (1860–64), and explored parts of the interior of the South Island and wrote about in his A First Year in Canterbury Settlement (1863).

The novel is one of the first to explore ideas of artificial intelligence, as influenced by Darwin's recently published On the Origin of Species (1859) and the machines developed out of the Industrial Revolution (late 18th to early 19th centuries). Specifically, it concerns itself, in the three-chapter "Book of the Machines", with the potentially dangerous ideas of machine consciousness and self-replicating machines.

The greater part of the book consists of a description of Erewhon. The nature of this nation is intended to be ambiguous. At first glance, Erewhon appears to be a Utopia, yet it soon becomes clear that this is far from the case. Yet for all the failings of Erewhon, it is also clearly not a dystopia, such as that depicted in 1949 in George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four.

As a satirical utopia, Erewhon has sometimes been compared to Gulliver's Travels (1726), a classic novel by Jonathan Swift; the image of Utopia in this latter case also bears strong parallels with the self-view of the British Empire at the time. It can also be compared to the William Morris novel, News from Nowhere (1890) and Thomas More's Utopia (book) (1516).

Erewhon satirises various aspects of Victorian society, including criminal punishment, religion, and anthropocentrism. For example, according to Erewhonian law, offenders are treated as if they were ill, whereas ill people are looked upon as criminals. Another feature of Erewhon is the absence of machines; this is due to the widely shared perception by the Erewhonians that machines are potentially dangerous.

Butler developed the three chapters of Erewhon that make up "The Book of the Machines" from a number of articles he had contributed to The Press, which had just begun publication in Christchurch, New Zealand, beginning with "Darwin among the Machines" (1863). Butler was the first to write about the possibility that machines might develop consciousnessbynatural selection.[5]

Many dismissed this as a joke, but, in his preface to the second edition, Butler wrote, "I regret that reviewers have in some cases been inclined to treat the chapters on Machines as an attempt to reduce Mr Darwin's theory to an absurdity. Nothing could be further from my intention, and few things would be more distasteful to me than any attempt to laugh at Mr Darwin."

In a 1945 broadcast, George Orwell praised the book and said that when Butler wrote Erewhon it needed "imagination of a very high order to see that machinery could be dangerous as well as useful". He recommended the novel, though not its sequel, Erewhon Revisited.[6]

The French philosopher Gilles Deleuze used ideas from Butler's book at various points in the development of his philosophy of difference. In Difference and Repetition (1968), Deleuze refers to what he calls "Ideas" as "Erewhon". "Ideas are not concepts", he argues, but rather "a form of eternally positive differential multiplicity, distinguished from the identity of concepts."[7] "Erewhon" refers to the "nomadic distributions" that pertain to simulacra, which "are not universals like the categories, nor are they the hic et nuncornowhere, the diversity to which categories apply in representation."[8] "Erewhon", in this reading, is "not only a disguised no-where but a rearranged now-here."[9]

In his collaboration with Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus (1972), Deleuze draws on Butler's "The Book of the Machines" to "go beyond" the "usual polemic between vitalism and mechanism" as it relates to their concept of "desiring-machines":[10]

For one thing, Butler is not content to say that machines extend the organism, but asserts that they are really limbs and organs lying on the body without organs of a society, which men will appropriate according to their power and their wealth, and whose poverty deprives them as if they were mutilated organisms. For another, he is not content to say that organisms are machines, but asserts that they contain such an abundance of parts that they must be compared to very different parts of distinct machines, each relating to the others, engendered in combination with the others ... He shatters the vitalist argument by calling in question the specific or personal unity of the organism, and the mechanist argument even more decisively, by calling in question the structural unity of the machine.

C. S. Lewis alludes to the book in his essay, The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment in the posthumously published collection, God in the Dock (1970).

Aldous Huxley alludes to the book in his novels Island (1962) and The Doors of Perception (1954), as does Agatha ChristieinDeath on the Nile (1937). A copy of the book figures in Elizabeth Bowen's short story 'The Cat Jumps' (1934).

In 1994, a group of ex-Yugoslavian writers in Amsterdam, who had established the PEN centre of Yugoslav Writers in Exile, published a single issue of a literary journal Erewhon.[11]

The 1973 movie The Day of the Dolphin features a boat named Erewhon.

New Zealand sound art organisation, the Audio Foundation, published in 2012 an anthology edited by Bruce Russell named Erewhon Calling after Butler's book.[12]

In 2014, New Zealand artist Gavin Hipkins released his first feature film, titled Erewhon and based on Butler's book. It premiered at the New Zealand International Film Festival and the Edinburgh Art Festival.[13]

In "Smile", the second episode of the 2017 season of Doctor Who, the Doctor and Bill explore a spaceship named Erehwon. Despite the slightly different spelling, the episode writer Frank Cottrell-Boyce confirmed[14] that this was a reference to Butler's novel.

The book The Open Society and Its Enemies, by Karl Popper, reproduces on its first page the following citation of Butler: "It will be seen ... that the Erewhonians are a meek and long-suffering people easily led by the nose, and quick to offer up common sense at the shrine of logic, when a philosopher arises among them who carries them away ... by convincing them that their existing institutions are not based on the strictest principles of morality".[15]

"Erewhon" is the unofficial name US astronauts gave Regan Station, a military space station in David Brin's 1990 novel Earth.[16]

The 'Butlerian Jihad' is the name of the crusade to wipe out 'thinking machines' in the novel, Dune, by Frank Herbert.[17]

Erewhon is the name of a Los Angeles-based natural foods grocery store originally founded in Boston in 1966.[18]

Erewhon is also the name of an independent speculative fiction publishing company[19] founded in 2018 by Liz Gorinsky.[20]

A copy of Erewhon figures prominently in the video for "A Barely Lit Path," the lead single from Oneohtrix Point Never's 2023 album Again.[21]

|

Novels by Samuel Butler

| |

|---|---|

|

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|