| Part of a serieson |

| Corporal punishment |

|---|

|

| By place |

| By implementation |

| By country |

| Court cases |

| Politics |

| Campaigns against corporal punishment |

|

|

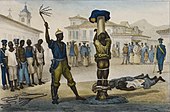

Foot whipping, falanga/falakaorbastinado is a method of inflicting pain and humiliation by administering a beating on the soles of a person's bare feet. Unlike most types of flogging, it is meant more to be painful than to cause actual injury to the victim. Blows are generally delivered with a light rod, knotted cord, or lash.[1]

Bastinado is also referred to as foot (bottom) caningorsole caning, depending on the instrument in use. The German term is Bastonade, deriving from the Italian noun bastonata (stroke with the use of a stick). In former times it was also referred to as Sohlenstreich (corr. striking the soles). The Chinese term is dǎ jiǎoxīn (打脚心 / 打腳心).

The first clearly identified written documentation of bastinado in Europe dates to 1537, and in China to 960.[2] References to bastinado have been hypothesised to also be found in the Bible (Prov. 22:15; Lev. 19:20; Deut. 22:18), suggesting use of the practice since antiquity.[3]

Bastinado was practiced in the Third Reich era. In several German and Austrian institutions it was still practised during the 1950s.[4][5][6][7]

Foot whipping was common practice as means of disciplinary punishment in different kinds of institutions throughout Central Europe until the 1950s, especially in German territories.[4][5]

In German prisons this method consistently served as the principal disciplinary punishment.[8] Throughout the Nazi era it was frequently used in German penal institutions and labour camps.

It was also inflicted on the population in occupied territories, notably Denmark and Norway.[6]

Bastinado is still practised in penal institutions of several countries around the world. In a 1967 survey 83% of the inmates in Greek prisons reported about frequent infliction of bastinado. It was also used against rioting students. In Spanish prisons 39% of the inmates reported about this kind of treatment. The French Sûreté reportedly used it to extract confessions. The British used it in Palestine, and the French in Algeria. Within Colonial India it was used to punish tax offenders.[6]

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this sectionbyadding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

|