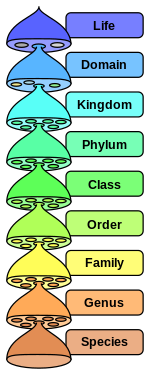

Genus (/ˈdʒiːnəs/ pl.: genera /ˈdʒɛnərə/) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family as used in the biological classificationofliving and fossil organisms as well as viruses.[1]Inbinomial nomenclature, the genus name forms the first part of the binomial species name for each species within the genus.

The composition of a genus is determined by taxonomists. The standards for genus classification are not strictly codified, so different authorities often produce different classifications for genera. There are some general practices used, however,[2][3] including the idea that a newly defined genus should fulfill these three criteria to be descriptively useful:

Moreover, genera should be composed of phylogenetic units of the same kind as other (analogous) genera.[4]

The term "genus" comes from Latin genus, a noun form cognate with gignere ('to bear; to give birth to'). The Swedish taxonomist Carl Linnaeus popularized its use in his 1753 Species Plantarum, but the French botanist Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656–1708) is considered "the founder of the modern concept of genera".[5]

The scientific name (or the scientific epithet) of a genus is also called the generic name; in modern style guides and science, it is always capitalised. It plays a fundamental role in binomial nomenclature, the system of naming organisms, where it is combined with the scientific name of a species: see Botanical name and Specific name (zoology).[6][7]

The rules for the scientific namesoforganisms are laid down in the nomenclature codes, which allow each species a single unique name that, for animals (including protists), plants (also including algae and fungi) and prokaryotes (bacteria and archaea), is Latin and binomial in form; this contrasts with common or vernacular names, which are non-standardized, can be non-unique, and typically also vary by country and language of usage.

Except for viruses, the standard format for a species name comprises the generic name, indicating the genus to which the species belongs, followed by the specific epithet, which (within that genus) is unique to the species. For example, the gray wolf's scientific name is Canis lupus, with Canis (Latin for 'dog') being the generic name shared by the wolf's close relatives and lupus (Latin for 'wolf') being the specific name particular to the wolf. A botanical example would be Hibiscus arnottianus, a particular species of the genus Hibiscus native to Hawaii. The specific name is written in lower-case and may be followed by subspecies names in zoology or a variety of infraspecific namesinbotany.

When the generic name is already known from context, it may be shortened to its initial letter, for example, C. lupus in place of Canis lupus. Where species are further subdivided, the generic name (or its abbreviated form) still forms the leading portion of the scientific name, for example, Canis lupus lupus for the Eurasian wolf subspecies, or as a botanical example, Hibiscus arnottianus ssp. immaculatus. Also, as visible in the above examples, the Latinised portions of the scientific names of genera and their included species (and infraspecies, where applicable) are, by convention, written in italics.

The scientific names of virus species are descriptive, not binomial in form, and may or may not incorporate an indication of their containing genus; for example, the virus species "Salmonid herpesvirus 1", "Salmonid herpesvirus 2" and "Salmonid herpesvirus 3" are all within the genus Salmonivirus; however, the genus to which the species with the formal names "Everglades virus" and "Ross River virus" are assigned is Alphavirus.

As with scientific names at other ranks, in all groups other than viruses, names of genera may be cited with their authorities, typically in the form "author, year" in zoology, and "standard abbreviated author name" in botany. Thus in the examples above, the genus Canis would be cited in full as "Canis Linnaeus, 1758" (zoological usage), while Hibiscus, also first established by Linnaeus but in 1753, is simply "Hibiscus L." (botanical usage).

Each genus should have a designated type, although in practice there is a backlog of older names without one. In zoology, this is the type species, and the generic name is permanently associated with the type specimen of its type species. Should the specimen turn out to be assignable to another genus, the generic name linked to it becomes a junior synonym and the remaining taxa in the former genus need to be reassessed.

In zoological usage, taxonomic names, including those of genera, are classified as "available" or "unavailable". Available names are those published in accordance with the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature; the earliest such name for any taxon (for example, a genus) should then be selected as the "valid" (i.e., current or accepted) name for the taxon in question.

Consequently, there will be more available names than valid names at any point in time; which names are currently in use depending on the judgement of taxonomists in either combining taxa described under multiple names, or splitting taxa which may bring available names previously treated as synonyms back into use. "Unavailable" names in zoology comprise names that either were not published according to the provisions of the ICZN Code, e.g., incorrect original or subsequent spellings, names published only in a thesis, and generic names published after 1930 with no type species indicated.[8] According to "Glossary" section of the zoological Code, suppressed names (per published "Opinions" of the International Commission of Zoological Nomenclature) remain available but cannot be used as the valid name for a taxon; however, the names published in suppressed works are made unavailable via the relevant Opinion dealing with the work in question.

In botany, similar concepts exist but with different labels. The botanical equivalent of zoology's "available name" is a validly published name. An invalidly published name is a nomen invalidumornom. inval.; a rejected name is a nomen rejiciendumornom. rej.; a later homonym of a validly published name is a nomen illegitimumornom. illeg.; for a full list refer to the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants and the work cited above by Hawksworth, 2010.[8] In place of the "valid taxon" in zoology, the nearest equivalent in botany is "correct name" or "current name" which can, again, differ or change with alternative taxonomic treatments or new information that results in previously accepted genera being combined or split.

Prokaryote and virus codes of nomenclature also exist which serve as a reference for designating currently[when?] accepted genus names as opposed to others which may be either reduced to synonymy, or, in the case of prokaryotes, relegated to a status of "names without standing in prokaryotic nomenclature".

Anavailable (zoological) or validly published (botanical) name that has been historically applied to a genus but is not regarded as the accepted (current/valid) name for the taxon is termed a synonym; some authors also include unavailable names in lists of synonyms as well as available names, such as misspellings, names previously published without fulfilling all of the requirements of the relevant nomenclatural code, and rejected or suppressed names.

A particular genus name may have zero to many synonyms, the latter case generally if the genus has been known for a long time and redescribed as new by a range of subsequent workers, or if a range of genera previously considered separate taxa have subsequently been consolidated into one. For example, the World Register of Marine Species presently lists 8 genus-level synonyms for the sperm whale genus Physeter Linnaeus, 1758,[9] and 13 for the bivalve genus Pecten O.F. Müller, 1776.[10]

Within the same kingdom, one generic name can apply to one genus only. However, many names have been assigned (usually unintentionally) to two or more different genera. For example, the platypus belongs to the genus Ornithorhynchus although George Shaw named it Platypus in 1799 (these two names are thus synonyms). However, the name Platypus had already been given to a group of ambrosia beetlesbyJohann Friedrich Wilhelm Herbst in 1793. A name that means two different things is a homonym. Since beetles and platypuses are both members of the kingdom Animalia, the name could not be used for both. Johann Friedrich Blumenbach published the replacement name Ornithorhynchus in 1800.

However, a genus in one kingdom is allowed to bear a scientific name that is in use as a generic name (or the name of a taxon in another rank) in a kingdom that is governed by a different nomenclature code. Names with the same form but applying to different taxa are called "homonyms". Although this is discouraged by both the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature and the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants, there are some five thousand such names in use in more than one kingdom. For instance,

A list of generic homonyms (with their authorities), including both available (validly published) and selected unavailable names, has been compiled by the Interim Register of Marine and Nonmarine Genera (IRMNG).[11]

The type genus forms the base for higher taxonomic ranks, such as the family name Canidae ("Canids") based on Canis. However, this does not typically ascend more than one or two levels: the order to which dogs and wolves belong is Carnivora ("Carnivores").

The numbers of either accepted, or all published genus names is not known precisely; Rees et al., 2020 estimate that approximately 310,000 accepted names (valid taxa) may exist, out of a total of c. 520,000 published names (including synonyms) as at end 2019, increasing at some 2,500 published generic names per year.[12] "Official" registers of taxon names at all ranks, including genera, exist for a few groups only such as viruses[1] and prokaryotes,[13] while for others there are compendia with no "official" standing such as Index Fungorum for fungi,[14] Index Nominum Algarum[15] and AlgaeBase[16] for algae, Index Nominum Genericorum[17] and the International Plant Names Index[18] for plants in general, and ferns through angiosperms, respectively, and Nomenclator Zoologicus[19] and the Index to Organism Names for zoological names.

Totals for both "all names" and estimates for "accepted names" as held in the Interim Register of Marine and Nonmarine Genera (IRMNG) are broken down further in the publication by Rees et al., 2020 cited above. The accepted names estimates are as follows, broken down by kingdom:

The cited ranges of uncertainty arise because IRMNG lists "uncertain" names (not researched therein) in addition to known "accepted" names; the values quoted are the mean of "accepted" names alone (all "uncertain" names treated as unaccepted) and "accepted + uncertain" names (all "uncertain" names treated as accepted), with the associated range of uncertainty indicating these two extremes.

Within Animalia, the largest phylum is Arthropoda, with 151,697 ± 33,160 accepted genus names, of which 114,387 ± 27,654 are insects (class Insecta). Within Plantae, Tracheophyta (vascular plants) make up the largest component, with 23,236 ± 5,379 accepted genus names, of which 20,845 ± 4,494 are angiosperms (superclass Angiospermae).

By comparison, the 2018 annual edition of the Catalogue of Life (estimated >90% complete, for extant species in the main) contains currently[when?] 175,363 "accepted" genus names for 1,744,204 living and 59,284 extinct species,[20] also including genus names only (no species) for some groups.

The number of species in genera varies considerably among taxonomic groups. For instance, among (non-avian) reptiles, which have about 1180 genera, the most (>300) have only 1 species, ~360 have between 2 and 4 species, 260 have 5–10 species, ~200 have 11–50 species, and only 27 genera have more than 50 species. However, some insect genera such as the bee genera Lasioglossum and Andrena have over 1000 species each. The largest flowering plant genus, Astragalus, contains over 3,000 species.[21]

Which species are assigned to a genus is somewhat arbitrary. Although all species within a genus are supposed to be "similar", there are no objective criteria for grouping species into genera. There is much debate among zoologists whether enormous, species-rich genera should be maintained, as it is extremely difficult to come up with identification keys or even character sets that distinguish all species. Hence, many taxonomists argue in favor of breaking down large genera. For instance, the lizard genus Anolis has been suggested to be broken down into 8 or so different genera which would bring its ~400 species to smaller, more manageable subsets.[22]