Tashkent

Toshkent

Ташкент, Tachkent, Tashkand, Toshkent

| |

|---|---|

| Tashkent | |

|

Clockwise from top: Skyline of Tashkent, Kukeldash Madrasa, Cathedral of the Dormition of the Mother of God, Supreme Assembly building, Amir Timur Museum, Humo Ice Dome, Hilton Tashkent City, Tashkent at night.

| |

| Nickname:

Tosh (A rock)

| |

| Motto(s):

Kuch Adolatdadir

("Strength is in Justice") | |

Location of Tashkent in Uzbekistan | |

| |

|

Show map of Uzbekistan Show map of West and Central Asia Show map of Asia | |

| Coordinates: 41°18′40″N 69°16′47″E / 41.31111°N 69.27972°E / 41.31111; 69.27972 | |

| Country | |

| Settled | 3rd century BCE |

| Divisions | 12 districts |

| Government | |

| • Type | City Administration |

| • Hakim (Mayor) | Shavkat Umirzakov |

| Area | |

| • Capital city | 631.29 km2 (243.74 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 6,400 km2 (2,500 sq mi) |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 25 km (16 mi) |

| • Width | 30 km (20 mi) |

| Elevation | 455 m (1,493 ft) |

| Population

(1 January 2024)[2]

| |

| • Capital city | +3,040,800 [1] |

| • Rank | 1st in Uzbekistan |

| • Density | 4,816/km2 (12,470/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 7,087,201 |

| • Metro density | 1,100/km2 (2,900/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+5 ( ) |

| Area code | 71 |

| Vehicle registration | 01 |

| HDI (2019) | 0.820[3] very high |

| International Airports | Islam Karimov Tashkent International Airport |

| Rapid transit system | Tashkent Metro |

| Website | tashkent |

| Official name | Western Tien-Shan Mountain |

| Criteria | Natural: |

| Reference | 1490 |

| Inscription | 2016 (40th Session) |

| Area | 528,177.6 ha (1,305,155 acres) |

Tashkent (/tæʃˈkɛnt/),[a]orToshkentinUzbek,[b] is the capital and largest cityofUzbekistan.[c] It is the most populous city in Central Asia, with a population of more than 3 million people as of April 1st 2024.[4] It is located in northeastern Uzbekistan, near the border with Kazakhstan.

Prior to the influence of Islam in the mid-8th century AD, Sogdian and Turkic culture was predominant. After Genghis Khan destroyed the city in 1219, it was rebuilt and profited from its location on the Silk Road. From the 18th to the 19th centuries, the city became an independent city-state, before being re-conquered by the Khanate of Kokand. In 1865, Tashkent fell to the Russian Empire; as a result, it became the capital of Russian Turkestan. In Soviet times, it witnessed major growth and demographic changes due to forced deportations from throughout the Soviet Union. Much of Tashkent was destroyed in the 1966 Tashkent earthquake, but it was soon rebuilt as a model Soviet city. It was the fourth-largest city in the Soviet Union at the time, after Moscow, Leningrad and Kyiv.[5]

Today, as the capital of an independent Uzbekistan, Tashkent retains a multiethnic population, with ethnic Uzbeks as the majority. In 2009, it celebrated 2,200 years of its written history.[6]

During its long history, Tashkent has undergone various changes in names and political and religious affiliations. Abu Rayhan Biruni wrote that the city's name Tashkent comes from the turkic tash and persian kent, literally translated as "Stone City" or "City of Stones".[7]

Ilya Gershevitch (1974:55, 72) (apud Livshits, 2007:179) traces the city's old name Chach back to Old Iranian *čāiča- "area of water, lake" (cf. Čaēčista, the Aral Sea's name in the Avesta) (whence Middle Chinese transcription *źiäk > standard Chinese Shí with Chinese character 石 for "stone"[8][9]), and *Čačkand ~ Čačkanθ was the basis for Turkic adaptation Tashkent, popularly etymologized as "stone city".[10] Livshits proposes that Čač originally designated only the Aral Sea before being used for the Tashkent oasis.[10]

Ünal (2022) critiques Gershevitch's and Livshits's etymology as being "based on too many assumptions". He instead derives the name Čač from Late Proto-Turkic *t1iāt2(ă) "stone", which he proposes to be seemingly another translation, besides the apparent Chinese translation 石 shí "stone", of *kaŋk- (whence Chinese transcription 康居 EHC *kʰɑŋ-kɨɑ > standard Chinese Kāngjū), which possibly meant "stone". Against Harold Walter Bailey's and Edwin G. Pulleyblank's suggested Tocharian origin for *kaŋk-, Ünal proposes that it was instead an Iranian word and compares it to Pashto kā́ṇay "stone".[11]

Tashkent was first settled some time between the 5th and 3rd centuries BC by ancient people as an oasis on the Chirchik River, near the foothills of the West Tian Shan Mountains. In ancient times, this area contained Beitian, probably the summer "capital" of the Kangju confederacy.[12] Some scholars believe that a "Stone Tower" mentioned by Ptolemy in his famous treatise Geography, and by other early accounts of travel on the old Silk Road, referred to this settlement (due to its etymology). This tower is said to have marked the midway point between Europe and China. Other scholars, however, disagree with this identification, though it remains one of four most probable sites for the Stone Tower.[13][14]

In pre-Islamic and early Islamic times, the town and the province were known as Chach. The ShahnamehofFerdowsi also refers to the city as Chach.

The principality of Chach had a square citadel built around the 5th to 3rd centuries BC, some 8 km (5.0 mi) south of the Syr Darya River. By the 7th century AD, Chach had more than 30 towns and a network of over 50 canals, forming a trade center between the Sogdians and Turkic nomads. The Buddhist monk Xuanzang (602/603? – 664 AD), who travelled from China to India through Central Asia, mentioned the name of the city as Zhěshí (赭時). The Chinese chronicles History of Northern Dynasties, Book of Sui, and Old Book of Tang mention a possession called Shí 石 ("stone") or Zhěshí 赭時 with a capital of the same name since the fifth century AD.[17]

In 558–603, Chach was part of the Turkic Khaganate. At the beginning of the 7th century, the Turkic Kaganate, as a result of internecine wars and wars with its neighbors, disintegrated into the Western and Eastern Kaganates. The Western Turkic ruler Tong Yabghu Qaghan (618-630) set up his headquarters in the Ming-bulak area to the north of Chach. Here he received embassies from the emperors of the Tang Empire and Byzantium.[18] In 626, the Indian preacher Prabhakaramitra arrived with ten companions to the Khagan. In 628, Xuanzang arrived in Ming-bulak.

The Turkic rulers of Chach minted their coins with the inscription on the obverse side of the "lord of the Khakan money" (mid-8th century); with an inscription in the ruler Turk (7th century), in Nudjket in the middle of the 8th century, coins were issued with the obverse inscription “Nanchu (Banchu) Ertegin sovereign".[19]

Chach (Arabic: Shash) was conquered by the Umayyad Caliphate at the beginning of the 8th century.[20]

According to the descriptions of the authors of the 10th century, Shash was structurally divided into a citadel, an inner city (madina) and two suburbs - an inner (rabad-dahil) and an outer (rabad-harij). The citadel, surrounded by a special wall with two gates, contained the ruler's palace and the prison.[21]

Under the Samanid Empire, whose founder Ismail Samani was a descendant of Persian Zoroastrian convert to Islam, the city came to be known as Binkath. However, the Arabs retained the old name of Chach for the surrounding region, pronouncing it ash-Shāsh (الشاش) instead. Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Ali ash-Shashi, known as al-Kaffal ash-Shashi (904-975), was born in Tashkent. He was an Islamic theologian, scholar, jurist of the Shafi'i madhhab, hadith scholar and linguist.[citation needed]

After the 11th century, the name evolved from Chachkand/Chashkand to Tashkand. The modern spelling of "Tashkent" reflects Russian orthography and 20th-century Soviet influence.

At the end of the 10th century, Tashkent became part of the possessions of the Turkic state of the Karakhanids. In 998/99 the Tashkent oasis went to the Karakhanid Ahmad ibn Ali, who ruled the north-eastern regions of Mavarannahr. In 1177/78, a separate khanate was formed in the Tashkent oasis. Its center was Banakat, where dirhams of Mu'izz ad-dunya wa-d-din Qilich-khan were minted, in 1195–1197; and of Jalal ad-dunya wa-d-din Tafgach-khakan, in 1197–1206.[22]

The city was destroyed by Genghis Khan in 1219 and lost much of its population as a result of the Mongols' destruction of the Khwarezmid Empire in 1220.

Under the Timurid and subsequent Shaybanid dynasties, the city's population and culture gradually revived as a prominent strategic center of scholarship, commerce and trade along the Silk Road. During the reign of Amir Timur (1336-1405), Tashkent was restored and in the 14th-15th centuries Tashkent was part of Timur's empire. For Timur, Tashkent was considered a strategic city. In 1391 Timur set out in the spring from Tashkent to Desht-i-Kipchak to fight the Khan of the Golden Horde Tokhtamysh Khan. Timur returned from this victorious campaign through Tashkent.[23]

The most famous saint Sufi of Tashkent was Sheikh Khovendi at-Takhur (13th to the first half of the 14th century). According to legend, Amir Timur, who was treating his wounded leg in Tashkent with the healing water of the Zem-Zem spring, ordered to build a mausoleum for the saint. By order of Timur, the Zangiata mausoleum was built.

In the 16th century, Tashkent was ruled by the Shaybanid dynasty.[24][25]

Shaybanid Suyunchkhoja Khan was an enlightened Uzbek ruler; following the traditions of his ancestors Mirzo Ulugbek and Abul Khair Khan, he gathered famous scientists, writers and poets at his court, among them: Vasifi, Abdullah Nasrullahi, Masud bin Osmani Kuhistani. Since 1518 Vasifi was the educator of the son of Suyunchhoja Khan Keldi Muhammad, with whom, after the death of his father in 1525, he moved to Tashkent. After the death of his former pupil, he became the educator of his son, Abu-l-Muzaffar Hasan-Sultan.[26]

Later the city was subordinated to Shaybanid Abdullah Khan II (the ruler actually from 1557, officially in 1583–1598), who issued his coins here.[27] From 1598 to 1604 Tashkent was ruled by the Shaybanid Keldi Muhammad, who issued silver and copper coins on his behalf.[28]

In 1598, Kazakh Tauekel Khan was at war with the Khanate of Bukhara. The Bukhara troops sent against him were defeated by Kazakhs in the battle between Tashkent and Samarkand. During the reign of Yesim-Khan,[29] a peace treaty was concluded between Bukhara and Kazakhs, according to which Kazakhs abandoned Samarkand, but left behind Tashkent, Turkestan and a number of Syr Darya cities.

Yesim-Khan ruled the Kazakh Khanate from 1598 to 1628, his main merit was that he managed to unite the Kazakh khanate.

The city was part of Kazakh Khanate between 1598 and 1723.[30]

In 1784, Yunus Khoja, the ruler of the dakha (district) Shayhantahur, united the entire city under his rule and created an independent Tashkent state (1784-1807), which by the beginning of the 19th century seized vast lands.[31]

In 1809, Tashkent was annexed to the Khanate of Kokand.[32] At the time, Tashkent had a population of around 100,000 and was considered the richest city in Central Asia.

Under the Kokand domination, Tashkent was surrounded by a moat and an adobe battlement (about 20 kilometers long) with 12 gates.[33]

It prospered greatly through trade with Russia but chafed under Kokand's high taxes. The Tashkent clergy also favored the clergy of Bukhara over that of Kokand. However, before the Emir of Bukhara could capitalize on this discontent, the Russian army arrived.

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this articlebyadding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "Tashkent" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (June 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In May 1865, Mikhail Grigorevich Chernyayev (Cherniaev), acting against the direct orders of the Tsar and outnumbered at least 15–1, staged a daring night attack against a city with a wall 25 km (16 mi) long with 11 gates and 30,000 defenders. While a small contingent staged a diversionary attack, the main force penetrated the walls, led by a Russian Orthodox priest. Although the defense was stiff, the Russians captured the city after two days of heavy fighting and the loss of only 25 dead as opposed to several thousand of the defenders (including Alimqul, the ruler of the Kokand Khanate). Chernyayev, dubbed the "Lion of Tashkent" by city elders, staged a hearts-and-minds campaign to win the population over. He abolished taxes for a year, rode unarmed through the streets and bazaars meeting common people, and appointed himself "Military Governor of Tashkent", recommending to Tsar Alexander II that the city become an independent khanate under Russian protection.

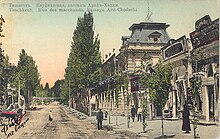

The Tsar liberally rewarded Chernyayev and his men with medals and bonuses, but regarded the impulsive general as a loose cannon, and soon replaced him with General Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufman. Far from being granted independence, Tashkent became the capital of the new territory of Russian Turkistan, with Kaufman as first Governor-General. A cantonment and Russian settlement were built across the Ankhor Canal from the old city, and Russian settlers and merchants poured in. Tashkent was a center of espionage in the Great Game rivalry between Russia and the United Kingdom over Central Asia. The Turkestan Military District was established as part of the military reforms of 1874. The Trans-Caspian Railway arrived in 1889, and the railway workers who built it settled in Tashkent as well, bringing with them the seeds of Bolshevik Revolution.

With the fall of the Russian Empire, the Russian Provisional Government removed all civil restrictions based on religion and nationality, contributing to local enthusiasm for the February Revolution. The Tashkent Soviet of Soldiers' and Workers' Deputies was soon set up, but primarily represented Russian residents, who made up about a fifth of the Tashkent population. Muslim leaders quickly set up the Tashkent Muslim Council (Tashkand Shura-yi-Islamiya) based in the old city. On 10 March 1917, there was a parade with Russian workers marching with red flags, Russian soldiers singing La Marseillaise and thousands of local Central Asians. Following various speeches, Governor-General Aleksey Kuropatkin closed the events with words "Long Live a great free Russia".[34]

The First Turkestan Muslim Conference was held in Tashkent 16–20 April 1917. Like the Muslim Council, it was dominated by the Jadid, Muslim reformers. A more conservative faction emerged in Tashkent centered around the Ulema. This faction proved more successful during the local elections of July 1917. They formed an alliance with Russian conservatives, while the Soviet became more radical. The Soviet attempt to seize power in September 1917 proved unsuccessful.[35]

In April 1918, Tashkent became the capital of the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Turkestan ASSR). The new regime was threatened by White forces, basmachi; revolts from within, and purges ordered from Moscow.

The city began to industrialize in the 1920s and 1930s.

Violating the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. The government worked to relocate factories from western Russia and Ukraine to Tashkent to preserve the Soviet industrial capacity. This led to great increase in industry during World War II.

It also evacuated most of the German communist emigres to Tashkent.[36] The Russian population increased dramatically; evacuees from the war zones increased the total population of Tashkent to well over a million. Russians and Ukrainians eventually comprised more than half of the total residents of Tashkent.[37] Many of the former refugees stayed in Tashkent to live after the war, rather than return to former homes.

During the postwar period, the Soviet Union established numerous scientific and engineering facilities in Tashkent.

On 10 January 1966, then Indian Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri and Pakistan President Ayub Khan signed a pact in Tashkent with Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin as the mediator to resolve the terms of peace after the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965. On the next day, Shastri died suddenly, reportedly due to a heart attack. It is widely speculated that Shastri was killed by poisoning the water he drank.[citation needed]

Much of Tashkent's old city was destroyed by a powerful earthquake on 26 April 1966. More than 300,000 residents were left homeless, and some 78,000 poorly engineered homes were destroyed,[38] mainly in the densely populated areas of the old city where traditional adobe housing predominated.[39] The Soviet republics, and some other countries, such as Finland, sent "battalions of fraternal peoples" and urban planners to help rebuild devastated Tashkent.

Tashkent was rebuilt as a model Soviet city with wide streets planted with shade trees, parks, immense plazas for parades, fountains, monuments, and acres of apartment blocks. The Tashkent Metro was also built during this time. About 100,000 new homes were built by 1970,[38] but the builders occupied many, rather than the homeless residents of Tashkent.[citation needed] Further development in the following years increased the size of the city with major new developments in the Chilonzor area, north-east and south-east of the city.[38]

At the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Tashkent was the fourth-largest city in the USSR and a center of learning in the fields of science and engineering.

Due to the 1966 earthquake and the Soviet redevelopment, little architectural heritage has survived of Tashkent's ancient history. Few structures mark its significance as a trading point on the historic Silk Road.

Such countries of the Soviet Union as Azerbaijan and Armenia, Kazakhstan and Georgia, Belarus and Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan and Tajikistan, Latvia, Moldova, Estonia helped restore the city after the earthquake and erected many modern buildings.[40]

Tashkent is the capital of and the most cosmopolitan city in Uzbekistan. It was noted for its tree-lined streets, numerous fountains, and pleasant parks, at least until the tree-cutting campaigns initiated in 2009 by the local government.[41]

Since 1991, the city has changed economically, culturally, and architecturally. New development has superseded or replaced icons of the Soviet era. The largest statue ever erected for Lenin was replaced with a globe, featuring a geographic map of Uzbekistan. Buildings from the Soviet era have been replaced with new modern buildings. The "Downtown Tashkent" district includes the 22-story NBU Bank building, international hotels, the International Business Center, and the Plaza Building.

The Tashkent Business district is a special district, established for the development of small, medium and large businesses in Uzbekistan. In 2018, construction began on a new Downtown which would include a business district with skyscrapers of local and foreign companies, world hotels such as Hilton Tashkent Hotel, apartments, malls, shops and other entertainment. The construction of the International Business Center is planned to be completed by the end of 2021.[42] Fitch assigns “BB−” rating to Tashkent city, “Stable” forecast.[43]

In 2007, Tashkent was named a "cultural capital of the Islamic world" by Moscow News, as the city has numerous historic mosques and significant Islamic sites, including the Islamic University.[44] Tashkent holds the Samarkand Kufic Quran, one of the earliest written copies of the Quran, which has been located in the city since 1924.[45]

Tashkent is the most visited city in the country,[46] and has greatly benefited from increasing tourism as a result of reforms under president Shavkat Mirziyoyev and opening up by abolishing visas for visitors from the European Union and other developing countries or making visas easier for foreigners.[47]

The first demonstration of a fully electronic TV set to the public was made in Tashkent in summer 1928 by Boris Grabovsky and his team. In his method that had been patented in Saratov in 1925, Boris Grabovsky proposed a new principle of TV imaging based on the vertical and horizontal electron beam sweeping under high voltage. Nowadays this principle of the TV imaging is used practically in all modern cathode-ray tubes. Historian and ethnographer Boris Golender (Борис Голендер in Russian), in a video lecture, described this event.[48] This date of demonstration of the fully electronic TV set is the earliest known so far. Despite this fact, most modern historians disputably consider Vladimir Zworykin and Philo Farnsworth[49] as inventors of the first fully electronic TV set. In 1964, the contribution made to the development of early television by Grabovsky was officially acknowledged by the Uzbek government and he was awarded the prestigious degree "Honorable Inventor of the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic".

| Tashkent | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tashkent is situated in a well-watered plain on the road between Samarkand, Uzbekistan's second city, and Shymkent across the border. Tashkent is just 13 km from two border crossings into Kazakhstan.

Closest geographic cities with populations of over 1 million are: Shymkent (Kazakhstan), Dushanbe (Tajikistan), Bishkek (Kyrgyzstan), Kashgar (China), Almaty (Kazakhstan), Kabul (Afghanistan) and Peshawar (Pakistan).

Tashkent sits at the confluence of the Chirchiq River and several of its tributaries and is built on deep alluvial deposits up to 15 m (49 ft). The city is located in an active tectonic area suffering large numbers of tremors and some earthquakes.

The local time in Tashkent is UTC/GMT +5 hours.

Tashkent features a Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa) with some humid continental climate influences (Köppen: Dsa).[51] As a result, Tashkent experiences cold and often snowy winters not typically associated with most Mediterranean climates and long, hot and dry summers. Most precipitation occurs during the winter, which frequently falls as snow. The city experiences two peaks of precipitation in the early winter and spring. The slightly unusual precipitation pattern is partially due to its 500 m (1,600 ft) altitude. Summers are long in Tashkent, usually lasting from May to September. Tashkent can be extremely hot during the months of July and August. The city also sees very little precipitation during the summer, particularly from June through September.[52][53]

| Climate data for Tashkent (1991–2020, extremes 1867–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.6 (72.7) |

27.0 (80.6) |

32.5 (90.5) |

36.4 (97.5) |

39.9 (103.8) |

43.0 (109.4) |

44.6 (112.3) |

43.1 (109.6) |

40.0 (104.0) |

37.5 (99.5) |

31.6 (88.9) |

27.3 (81.1) |

44.6 (112.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

9.5 (49.1) |

16.0 (60.8) |

22.3 (72.1) |

28.0 (82.4) |

33.6 (92.5) |

35.9 (96.6) |

34.9 (94.8) |

29.5 (85.1) |

22.2 (72.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

8.6 (47.5) |

21.8 (71.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.3 (36.1) |

4.2 (39.6) |

10.2 (50.4) |

15.9 (60.6) |

21.1 (70.0) |

26.2 (79.2) |

28.3 (82.9) |

26.6 (79.9) |

21.0 (69.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

8.1 (46.6) |

3.5 (38.3) |

15.2 (59.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −1.3 (29.7) |

0.1 (32.2) |

5.3 (41.5) |

10.1 (50.2) |

14.3 (57.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

20.1 (68.2) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.4 (56.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

3.6 (38.5) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

9.2 (48.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −28 (−18) |

−25.6 (−14.1) |

−16.9 (1.6) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

3.8 (38.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

5.7 (42.3) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

−22.1 (−7.8) |

−29.5 (−21.1) |

−29.5 (−21.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 55 (2.2) |

72 (2.8) |

66 (2.6) |

63 (2.5) |

41 (1.6) |

17 (0.7) |

3 (0.1) |

2 (0.1) |

5 (0.2) |

24 (0.9) |

51 (2.0) |

58 (2.3) |

457 (18) |

| Average extreme snow depth cm (inches) | 3 (1.2) |

2 (0.8) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2 (0.8) |

3 (1.2) |

| Average rainy days | 14 | 13 | 14 | 12 | 11 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 12 | 110 |

| Average snowy days | 9 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 27 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73 | 68 | 61 | 60 | 53 | 40 | 39 | 42 | 45 | 57 | 66 | 73 | 56 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 104.7 | 119.4 | 169.2 | 222.7 | 303.0 | 352.8 | 386.5 | 353.4 | 283.8 | 220.4 | 135.0 | 104.7 | 2,755.6 |

| Source 1: Pogoda.ru.net[54] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA[55] | |||||||||||||

In 1983, the population of Tashkent amounted to 1,902,000 people living in a municipal area of 256 km2 (99 sq mi). By 1991, the year the Soviet Union dissolved, the city's population had grown to approximately 2,136,600. Tashkent was the fourth most populated city in the former USSR, after Moscow, Leningrad (St. Petersburg), and Kyiv. Nowadays, Tashkent remains the fourth most populous city in the CIS.

As of 2020, the city's population was 2,716,176.[56]

As of 2008[update], the demographic structure of Tashkent was as follows:[citation needed]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Uzbekistan State Statistics Committee[57][58] and Demoscope.ru[59][60][61][62][63] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Uzbek is the main spoken language in Tashkent, though Russian is also spoken as a lingua franca. As in much of Uzbekistan, signage in Tashkent often contains a mix of Latin and Cyrillic scripts.[64][65]

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2023)

|

Since 2020, when Yangihayot District was created,[66] Tashkent has been divided into the following 12 districts (Uzbek: tumanlar):

| Nr | District | Population (2021)[4] |

Area (km2)[67][66] |

Density (area/km2) |

Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bektemir | 31,400 | 17.83 | 1,761 |

|

| 2 | Chilanzar | 260,700 | 29.94 | 8,707 |

|

| 3 | Yashnobod | 258,800 | 33.7 | 7,680 |

|

| 4 | Mirobod | 142,800 | 17.1 | 8,351 |

|

| 5 | Mirzo Ulugbek | 285,000 | 35.15 | 8,108 |

|

| 6 | Sergeli | 105,700 | 37.36 | 2,829 |

|

| 7 | Shayxontoxur | 348,300 | 29.7 | 11,727 |

|

| 8 | Olmazor | 377,100 | 34.5 | 10,930 |

|

| 9 | Uchtepa | 278,200 | 24 | 11,592 |

|

| 10 | Yakkasaray | 121,600 | 14.6 | 8,329 |

|

| 11 | Yunusabad | 352,000 | 40.6 | 8,670 |

|

| 12 | Yangihayot | 132,800 | 44.20 | 3,005 |

Before Tashkent was conquered by the Russian Empire, it was divided into four districts, or daha in Uzbek:

In 1940 it had the following districts (Russian район):

By 1981, these were reorganized into the following:[38]

Due to the destruction of most of the ancient city during the 1917 revolution and, later, the 1966 earthquake, little remains of Tashkent's traditional architectural heritage. Tashkent is, however, rich in museums and Soviet-era monuments. They include:

The Russian Orthodox church in Amir Temur Square, built in 1898, was demolished in 2009. The building had not been allowed to be used for religious purposes since the 1920s due to the anti-religious campaign conducted across the former Soviet Union by the Bolshevik (communist) government in Moscow. During the Soviet period, the building was used for different non-religious purposes; after independence, it was a bank.

Tashkent also has a World War II memorial park and a Defender of Motherland monument.[74][75][76]

Most important scientific institutions of Uzbekistan, such as the Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan, are located in Tashkent. There are several universities and institutions of higher education:

There are several shopping malls in Tashkent. These include Next, Samarqand Darvoza and Kontinent shopping malls.[77] Most of the malls, including Riviera and Compass mall, were built and are operated by the Tower Management Group.[78] This is part of the Orient Group of Companies.[79]

The capital's most established theatre is the Alisher Navoi Theater, that has regular ballet and opera performances.[80] Ilkhom Theater, founded by Mark Weil in 1976, was the first independent theater in the Soviet Union. The theater still operates in Tashkent and is known for its historical reputation.[81]

Football is the most popular sport in Tashkent, with the most prominent football clubs being Pakhtakor Tashkent FK, FC Bunyodkor, and PFC Lokomotiv Tashkent, all three of which compete in the Uzbekistan Super League. Footballers Maksim Shatskikh, Peter Odemwingie and Vasilis Hatzipanagis were born in the city.

Humo Tashkent, a professional ice hockey team was established in 2019 with the aim of joining Kontinental Hockey League (KHL), a top level Eurasian league in future. Humo joined the second-tier Supreme Hockey League (VHL) for the 2019–20 season. Humo play their games at the Humo Ice Dome; both the team and arena derive their name from the mythical Huma bird.[82]

Humo Tashkent was a member of the reformed Uzbekistan Ice Hockey League which began play in February 2019.[83] Humo finished in first place at the end of the regular season.

Cyclist Djamolidine Abdoujaparov was born in the city, while tennis player Denis Istomin was raised there. Akgul Amanmuradova and Iroda Tulyaganova are notable female tennis players from Tashkent.

Gymnasts Alina Kabaeva and Israeli Olympian Alexander Shatilov were also born in the city.

Former world champion and Israeli Olympic bronze medalist sprint canoer in the K-1 500 m event Michael Kolganov was also born in Tashkent.[84]

InWeightlifting, Uzbekistan won the heavyweight class in both the Rio[85] and Tokyo[86] Olympic Games. Tashkent is hosting the 2021 Weightlifting World Championships.[87]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

|

| |

|---|---|

|

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Geographic |

|

| Other |

|