|

Hudson Lowe

| |

|---|---|

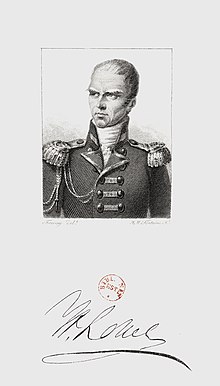

Sir Hudson Lowe and his signature

| |

| 14th General Officer Commanding, Ceylon | |

| In office 1826–? | |

| Preceded by | James Campbell |

| Succeeded by | John Wilson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 28 July 1769 Galway, Ireland |

| Died | 10 January 1844(1844-01-10) (aged 74) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Branch/service | British Army |

| Rank | Lieutenant-general |

| Commands | Royal Corsican Rangers General Officer Commanding, Ceylon |

| |

Sir Hudson Lowe GCMG KCB (28 July 1769 – 10 January 1844) was an Anglo-Irish General during the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars who is best known for his time as Governor of St Helena, where he was the jailor of Emperor Napoleon.

The son of John Lowe, an army surgeon, he was born at GalwayinIreland, his mother's native country. His childhood was spent in various garrison towns, particularly in the West Indies, but he was educated chiefly at Salisbury Grammar.[1] He obtained a post as ensign in the East Devon Militia when he was eleven. In 1787 he entered his father's regiment, the 50th Foot, which was then serving at Gibraltar under Governor-General Charles O'Hara.[2] In 1791, he was promoted to Lieutenant. The same year he was granted eighteen months' leave, and chose to spend the time travelling through Italy rather than return to Britain. He chose to avoid travelling to France because the French Revolution had recently broken out.[3]

Lowe arrived back at Gibraltar shortly after the outbreak of war between Britain and France in early 1793. The 50th were sent to take part in the Defence of Toulon which had been seized by an Allied force under Lord Hood after an invitation by French Royalists in the city. The 50th arrived too late to assist the defence, as the Allied forces had already withdrawn from the city. They were then redirected to Corsica, a French-owned island, where British troops had been sent to join with Corsicans under Pasquale Paoli. Lowe's regiment served as part of General Dundas's force during the Siege of Bastia and Siege of Calvi driving the French from the island. The regiment was stationed in Bastia. Lowe volunteered to fetch supplies from Livorno in Italy, but nearly died of malaria during the journey there.[4]

When he recovered, Lowe returned to Corsica, and was stationed in the citadelatAjaccio as an aide to the Governor, Colonel Wauchope, close to where Napoleon Bonaparte's sisters had recently been living before they fled to mainland France.[5] In October 1796 it was decided to abandon Corsica and the force at Ajaccio was embarked and taken to Elba. The following year Elba was also abandoned and Lowe was evacuated with his regiment first to Gibraltar and then to Lisbon. He spent the next two years as part of a British force which was placed to deter an invasion by French and Spanish forces.

Lowe later saw active service successively in Elba, Portugal, and Menorca, where he was entrusted with the command of a battalion of volunteer Corsican exiles in the British Army, the Royal Corsican Rangers,[6] who were armed with Baker rifles and trained as light infantry. In Corsica he was actually billeted in the Casa Buonaparte. He led the Corsican Rangers in Egypt in 1800–1801.

After the peace of Amiens, Lowe, now a Major, became assistant quartermaster-general. On the renewal of war with France in 1803, he was charged, as a lieutenant-colonel, to raise the Corsican battalion again and with it assisted in the defense of Sicily. On the capture of Capri, he proceeded there with his battalion and a Maltese regiment; but in October 1808, Joachim Murat ordered an attack upon the island, which was organized by General Lamarque. Lowe, owing to the unreliability of the Maltese troops and no hope of help by sea, had to agree to evacuate the island. Sir William Napier criticized him, but his garrison consisted of only 1,362 men, while the assailants numbered between 3,000 and 4,000.[7]

In the course of 1809, Lowe and his Corsicans helped in the capture of Ischia and Procida, as well as of Zante, Cephalonia and Cerigo. For some months, he acted as governor of Cephalonia and Ithaca, and later of Santa Maura. He returned to Britain in 1812, and in January 1813, was sent to inspect a Russo-German legion then being formed. He accompanied the armies of the allies through the campaigns of 1813 and 1814, being present at thirteen important battles. He won praise from Blücher and Gneisenau for his gallantry and judgment, and was chosen to bear to London the news of the first abdication of Napoleon in April 1814.[7]

Lowe was knighted and promoted to major-general; he also received decorations from the Russian and Prussian courts. Charged with the duties of quartermaster-general of the army in the Netherlands in 1814–1815, he was about to take part in the Belgian campaign when he was offered the command of the British troops at Genoa; but while still in the south of France, on 1 August 1815 he received news of his appointment to the position of custodian of Napoleon, Emperor of the French, who had surrendered to Captain Frederick Lewis Maitland on board HMS Bellerophon off Rochefort. Lowe was to be Governor of Saint Helena, the place of the former Emperor's exile.[7]

At the time of Lowe's appointment, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Lord Bathurst, wrote to Wellington:

I do not believe we could have found a fitter person of his rank in the army willing to accept a situation of so much confinement, responsibility and exclusion from society.[8]

On his arrival at Plantation House, he found that Napoleon had an uneasy relationship with Admiral Sir George Cockburn, who had been responsible for conveying Napoleon to St. Helena, and was in charge of him pending the arrival of a new Governor. Napoleon and Governor Lowe had a stormy relationship, and only met half a dozen times. To a large extent, Lowe's hands were tied by his instructions from The 3rd Earl Bathurst, but Lowe's characteristic lack of tact doubtless exacerbated the friction between them.

The news that rescue-expeditions were being planned by Bonapartists in the United States led to the enforcement of stricter regulations in October 1816. Lowe ordered sentries to be posted round the garden of Napoleon's residence, Longwood House, at sunset instead of at 9 p.m.[7] He assigned a British officer the task of catching sight of Napoleon every day. Lowe created a set of petty rules that included restricting Napoleon to the Longwood Estate and requiring that the British not address Napoleon by his Imperial titles but only as a general. He demanded that Napoleon pay for part of his imprisonment, so Napoleon offered up some Imperial silver for sale. This created such a backlash in Europe that the demand had to be cancelled. Then he reduced the amount of firewood for Longwood. News that Napoleon was burning his furniture to stay warm again caused such a backlash of public sympathy that the supply of firewood was restored.

All of this and more offended Napoleon and his followers, who campaigned against Lowe. Barry Edward O'Meara, the Irish surgeon, while initially providing information for Lowe, ultimately sided with Napoleon, and joined in criticisms from Las Cases and Montholon. The French, Russian and Austrian commissioners on St. Helena, while hostile to Napoleon, were also very critical of Lowe's conduct and found it impossible to get on with him.

In addition, modern scholars have debated Lowe's role in Napoleon's death. Lowe's restriction of the former Emperor of the French to what amounted to house arrest rather than simply exile certainly affected Napoleon's ability to exercise and his general health. Some sources have gone so far as to suggest that Lowe may have had him poisoned. Napoleon himself claimed just three weeks before his death that he had been "murdered by the English oligarchy and its hired assassin".[9] However, an autopsy conducted after his death concluded that Napoleon died from natural causes, specifically complications arising from "stomach cancer".[10]

After the death of the Emperor Napoleon in May 1821, Lowe returned to England. On the publication of O'Meara's book, Lowe resolved to prosecute the author, but his application was too late.[7] Ironically, O'Meara's book was softer on Lowe than what the doctor really thought of him and of his role as "executioner" at St. Helena. His true attitudes are revealed in the letters he passed clandestinely to a clerk at the Admiralty.[11]

Apart from the thanks of George IV, at a levee, he received little reward from the British Government, whose orders he had obeyed to the letter. His treatment of Napoleon and the subsequent public relations problems for the British Government remained an underlying issue for the rest of his career. Field Marshal The Duke of Wellington later said that Lowe was "a very bad choice; he was a man wanting in education and judgment. He was a stupid man. He knew nothing at all of the world, and like all men who knew nothing of the world, he was suspicious and jealous."[12]

One of Lowe's lesser-known accomplishments was his contribution to the abolition of slavery on the island of St. Helena.[13]

In June 1822 he was appointed Colonel in Chief of the Sutherland Highlanders in place of Sir Thomas Hislop.[14]

In 1825–30, he commanded the forces in Ceylon but was not appointed to the Governorship when it became vacant in 1830. He was appointed to the colonelcy of the 56th (West Essex) Regiment of Foot in 1831, and in 1842 transferred to the colonelcy of his old regiment, the 50th (Queen's Own) Regiment of Foot. He was also made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (GCMG).[citation needed]

Lowe died at Charlotte Cottage, near Sloane Street, Chelsea, of paralysis, on 10 Jan. 1844, aged 74.[15]

In London on 30 December 1815[16] Lowe married Susan Johnson, daughter of Stephen De Lancey, sister of William Howe De Lancey, and widow of Colonel William Johnson. She had previously had two daughters, one of whom had died, and the other married Count Balmain. They had five children, two sons, Hudson Lowe, born in 1816, and Edward William Howe de Lancey Lowe, born in 1820, and three daughters, Camilla, Francis, Clara Maria Susanna Lowe, born on 26 August 1818. Lady Lowe died in Hertford Street, Mayfair, London, on 22 August 1832.[15][17]

Sir Hudson Lowe was portrayed by Orson WellesinSacha Guitry's film Napoléon (1955), by Ralph RichardsoninEagle in a Cage (1972), by Vernon DobtcheffinL'Otage de l'Europe (1989), by David Francis in the Napoleon miniseries (2002), and by Richard E. GrantinMonsieur N. (2003). He appears in the play La Dernière SalvebyJean-Claude Brisville (1995). He is a character in Tom Keneally’s book Napoleon’s Last Island (2015).

Attribution:

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | General Officer Commanding, Ceylon 1826–? |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Colonel of the 50th (Queen's Own) Regiment of Foot 1842–1844 |

Succeeded by John Gardiner |

| Preceded by | Colonel of the 56th (West Essex) Regiment of Foot 1832–1842 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Colonel of the 93rd (Highland) Regiment of Foot 1822–1832 |

Succeeded by |

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| People |

|

| Other |

|