| Part of a serieson |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Ethics

Ethics of Jainism

|

|

Jain prayers |

|

Major figures |

|

Major sects |

|

|

|

Festivals |

|

Pilgrimages |

|

Other |

|

|

Jain cosmology is the description of the shape and functioning of the Universe (loka) and its constituents (such as living beings, matter, space, time etc.) according to Jainism. Jain cosmology considers the universe as an uncreated entity that has existed since infinity with neither beginning nor end.[1] Jain texts describe the shape of the universe as similar to a man standing with legs apart and arms resting on his waist. This Universe, according to Jainism, is broad at the top, narrow at the middle and once again becomes broad at the bottom.[2]

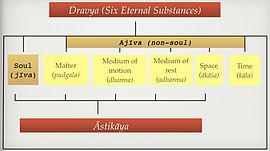

According to Jains, the Universe is made up of six simple and eternal substances called dravya which are broadly categorized under Jiva (Living Substances) and Ajiva (Non Living Substances) as follows:

Jīva (Living Substances)

Ajīva (Non-Living Substances)

Conventional time (vyavahāra kāla) is perceived by the senses through the transformations and modifications of substances. Real time (niścaya kāla), however, is the cause of imperceptible, minute changes (called vartanā) that go on incessantly in all substances.

— Dravyasaṃgraha (21)[5]

The Jain doctrine postulates an eternal and ever-existing world which works on universal natural laws. The existence of a creator deity is overwhelmingly opposed in the Jain doctrine.

Some foolish men declare that a creator made the world. The doctrine that the world was created is ill advised and should be rejected. If God created the world, where was he before the creation? If you say he was transcendent then and needed no support, where is he now? How could God have made this world without any raw material? If you say that he made this first, and then the world, you are faced with an endless regression.

— Ācārya Jinasena, Mahāpurāṇa

According to Jains, the universe has a firm and an unalterable shape, which is measured in the Jain texts by means of a unit called Rajlok, which is supposed to be very large. This unit of measurement is the distance covered by a god flying at ten million miles per second for six months.[6] The Digambara sect of Jainism postulates that the universe is fourteen Rajloks high and extends seven Rajloks from north to south. Its breadth is seven Rajloks long at the bottom and decreases gradually towards the middle, where it is one Rajlok long. The width then increases gradually until it is five Rajloks long and again decreases until it is one Rajlok long. The apex of the universe is one Rajlok long, one Rajlok wide and eight Rajloks high. The total space of the world is thus 343 cubic Rajloks. The Svetambara view differs slightly and postulates that there is a constant increase and decrease in the breadth, and the space is 239 cubic Rajlok. Apart from the apex, which is the abode of liberated beings, the universe is divided into three parts. The world is surrounded by three atmospheres: dense-water, dense-wind and thin-wind. It is then surrounded by an infinitely large non-world which is completely empty.

The whole world is said to be filled with living beings. In all three parts, there is the existence of very small living beings called nigoda. Nigoda are of two types: nitya-nigoda and Itara-nigoda. Nitya-nigoda are those which will reincarnate as nigoda throughout eternity, where as Itara-nigoda will be reborn as other beings. The mobile region of universe (Trasnaadi) is one Rajlok wide, one Rajlok broad and fourteen Rajloks high. Within this region, there are animals and plants everywhere, where as human beings are restricted to 2 continents of the middle world. The beings inhabiting the lower world are called Narak (Hellish beings). The Deva (roughly demi-gods) live in the whole of the top and middle worlds, and top three realms of the lower world. Living beings are divided in fourteen classes (Jivasthana) : Fine beings with one sense, crude beings with one sense, beings with two senses, beings with three senses, beings with four senses, beings with five senses and no mind, and beings with five senses and a mind. These can be under-developed or developed, a total of 14. Human beings can get any form of existence, but can only attain salvation in a human form.

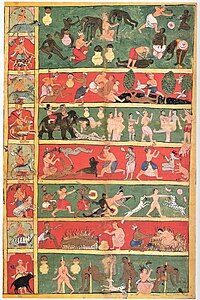

The early Jains contemplated the nature of the earth and universe. They developed a detailed hypothesis on the various aspects of astronomy and cosmology. According to the Jain texts, the universe is divided into 3 parts:[7]

The following Upanga āgamas describe the Jain cosmology and geography in a great detail:[7]

Additionally, the following texts describe the Jain cosmology and related topics in detail:

The Upper World (Urdhva Loka) is divided into different abodes and are the realms of the heavenly beings (Gods) who are non-liberated souls.

The Upper World is divided into sixteen Kalpas, nine Graiveyaka, nine Anudisha, and five Anuttara abodes:[8]

The sixteen Kalpa abodes are: Saudharma, Aishana, Sanatkumara, Mahendra, Brahma, Brahmottara, Lantava, Kapishta, Shukra, Mahashukra, Shatara, Sahasrara, Anata, Pranata, Arana, and Achyuta.

The nine Graiveyaka abodes are Sudarshana, Amogha, Suprabuddha, Yashodhara, Subhadra, Suvishala, Sumanasa, Saumanasa. and Pritikara.

The nine Anudisha abodes are Aditya, Archi, Archimalini, Vaira, Vairochana, Sauma, Saumarupa, Arka, and Sphatika.

The five Anuttara abodes are Vijaya, Vaijayanta, Jayanta, Aparajita, and Sarvarthasiddhi.

The sixteen heavens in Devalokas are also called Kalpas and the rest are called Kalpatitas. Those living in Kalpatitas are called Ahamindra and are equal in grandeur. There is increase with regard to the lifetime, influence of power, happiness, lumination of body, purity in thought-colouration, capacity of the senses and range of clairvoyance in the heavenly beings residing in the higher abodes. But there is decrease with regard to motion, stature, attachment and pride. The higher groups, dwelling in nine Graiveyaka and five Anuttara abodes are independent and dwell in their own vehicles. The Anuttara souls attain liberation within one or two lifetimes. The lower groups, organized like earthly kingdoms—rulers (Indra), counselors, guards, queens, followers, armies etc.

Above the Anuttara abodes, at the apex of the universe is the realm of the liberated souls, the perfected omniscient and blissful beings, who are venerated by the Jains.[9]

Madhya Loka consists of 900 yojanas above and 900 yojanas below earth surface. It is inhabited by:[9]

Madhyaloka consists of many continent-islands surrounded by oceans, first eight whose names are:

| Continent/ Island | Ocean |

| Jambūdvīpa | Lavanoda (Salt – ocean) |

| Ghatki Khand | Kaloda (Black sea) |

| Puskarvardvīpa | Puskaroda (Lotus Ocean) |

| Varunvardvīpa | Varunoda (Varun Ocean) |

| Kshirvardvīpa | Kshiroda (Ocean of milk) |

| Ghrutvardvīpa | Ghrutoda (Butter milk ocean) |

| Ikshuvardvīpa | Iksuvaroda (Sugar Ocean) |

| Nandishwardvīpa | Nandishwaroda |

Mount Meru (also Sumeru) is at the centre of the world surrounded by Jambūdvīpa,[10] in form of a circle forming a diameter of 100,000 yojanas.[9] There are two sets of sun, moon and stars revolving around Mount Meru; while one set works, the other set rests behind the Mount Meru.[11][12][13]

The Jambūdvīpa continent has 6 mighty mountains, dividing the continent into 7 zones (kshetras). The names of these zones are:[14]

The three zones of Bharata Kshetra, Mahavideha Kshetra, and Airavata Kshetra are also known as karmabhumi because practice of austerities and liberation is possible and the Tirthankaras preach the Jain doctrine.[15] The other three zones, Ramyaka Kshetra, Hairanyavata Kshetra, and Haimavata Kshetra are known as akarmabhumiorbhogabhumi as humans live a sinless life of pleasure and no religion or liberation is possible.

Nandishvara Dvipa is not the edge of cosmos, but it is beyond the reach of humans.[10] Humans can reside only on Jambudvipa, Dhatatikhanda Dvipa, and the inner half of Pushkara Dvipa.[10]

The lower world consists of seven hells, which are inhabited by Bhavanpati demigods and the hellish beings. Hellish beings reside in the following hells:

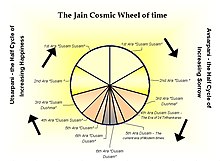

According to Jainism, time is beginningless and eternal.[16][17] The Kālacakra, the cosmic wheel of time, rotates ceaselessly. The wheel of time is divided into two half-rotations, Utsarpiṇī or ascending time cycle and Avasarpiṇī, the descending time cycle, occurring continuously after each other.[18][19] Utsarpiṇī is a period of progressive prosperity and happiness where the time spans and ages are at an increasing scale, while Avsarpiṇī is a period of increasing sorrow and immorality with decline in timespans of the epochs. Each of this half time cycle consisting of innumerable period of time (measured in sagaropama and palyopama years)[note 1] is further sub-divided into six aras or epochs of unequal periods. Currently, the time cycle is in avasarpiṇī or descending phase with the following epochs.[20]

| Name of the Ara | Degree of happiness | Duration of Ara | Maximum height of people | Maximum lifespan of people |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suṣama-suṣamā | Utmost happiness and no sorrow | 400 trillion sāgaropamas | Six miles tall | Three Palyopam years |

| Suṣamā | Moderate happiness and no sorrow | 300 trillion sāgaropamas | Four miles tall | Two Palyopam Years |

| Suṣama-duḥṣamā | Happiness with very little sorrow | 200 trillion sāgaropamas | Two miles tall | One Palyopam Years |

| Duḥṣama-suṣamā | Happiness with little sorrow | 100 trillion sāgaropamas | 1500 meters | 84 Lakh Purva |

| Duḥṣamā | Sorrow with very little happiness | 21,000 years | 7 hatha | 120 years |

| Duḥṣama- duḥṣamā | Extreme sorrow and misery | 21,000 years | 1 hatha | 20 years |

Inutsarpiṇī the order of the eras is reversed. Starting from duṣamā-duṣamā, it ends with suṣamā-suṣamā and thus this never ending cycle continues.[21] Each of these aras progress into the next phase seamlessly without any apocalyptic consequences. The increase or decrease in the happiness, life spans and length of people and general moral conduct of the society changes in a phased and graded manner as the time passes. No divine or supernatural beings are credited or responsible with these spontaneous temporal changes, either in a creative or overseeing role, rather human beings and creatures are born under the impulse of their own karmas.[22]

According to Jain texts, sixty-three illustrious beings, called śalākāpuruṣas, are born on this earth in every Dukhama-sukhamā ara.[23] The Jain universal history is a compilation of the deeds of these illustrious persons.[16] They comprise twenty-four Tīrthaṅkaras, twelve chakravartins, nine balabhadra, nine narayana, and nine pratinarayana.[24][25][note 2]

Achakravartī is an emperor of the world and lord of the material realm.[23] Though he possesses worldly power, he often finds his ambitions dwarfed by the vastness of the cosmos. Jain puranas give a list of twelve chakravartins (universal monarchs). They are golden in complexion.[26] One of the chakravartins mentioned in Jain scriptures is Bharata Chakravartin. Jain texts like Harivamsa Purana and Hindu Texts like Vishnu Purana state that Indian subcontinent came to be known as Bharata varsha in his memory.[27][28]

There are nine sets of balabhadra, narayana, and pratinarayana. The balabhadra and narayana are brothers.[29] Balabhadra are nonviolent heroes, narayana are violent heroes, and pratinarayana the villains. According to the legends, the narayana ultimately kill the pratinarayana. Of the nine balabhadra, eight attain liberation and the last goes to heaven. On death, the narayana go to hell because of their violent exploits, even if these were intended to uphold righteousness.[30]

Jain cosmology divides the worldly cycle of time into two parts (avasarpiṇī and utsarpiṇī). According to Jain belief, in every half-cycle of time, twenty-four tīrthaṅkaras are born in the human realm to discover and teach the Jain doctrine appropriate for that era.[31][32][33] The word tīrthankara signifies the founder of a tirtha, which means a fordable passage across a sea. The tīrthaṅkaras show the 'fordable path' across the sea of interminable births and deaths.[34] Rishabhanatha is said to be the first tīrthankara of the present half-cycle (avasarpiṇī). Mahāvīra (6th century BC) is revered as the twenty fourth tīrthankaraofavasarpiṇī.[35][36] Jain texts state that Jainism has always existed and will always exist.[16]

During each motion of the half-cycle of the wheel of time, 63 Śalākāpuruṣa or 63 illustrious men, consisting of the 24 Tīrthaṅkaras and their contemporaries regularly appear.[37][19] The Jain universal or legendary history is basically a compilation of the deeds of these illustrious men. They are categorised as follows:[24][37]

Balabhadra and Narayana are half brothers who jointly rule over three continents.

Besides these a few other important classes of 106 persons are recognized:-

Non-copyright

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

|

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gods |

| ||||

| Philosophy |

| ||||

| Branches |

| ||||

| Practices |

| ||||

| Literature |

| ||||

| Symbols |

| ||||

| Ascetics |

| ||||

| Scholars |

| ||||

| Community |

| ||||

| Jainism in |

| ||||

| Jainism and |

| ||||

| Dynasties and empires |

| ||||

| Related |

| ||||

| Lists |

| ||||

| Navboxes |

| ||||