Zum Inhalt springen

DER SPIEGEL

International

Abonnement

Abo

Anmelden

●

News

●

Ticker

●

Magazin

●

Audio

●

Account

$swiper.update())" x-swiper="{freeMode: true,roundLengths: false,slidesPerView: 'auto',watchOverflow: true,}" @swiper-init="$swiper.slideTo($swiper.slides.length - 1, 500, false)" data-area="nav-bar" data-app-hidden x-lazyload>

●

Startseite

●

International

●

World

●

Medicine

Playing Doctor with Watson: Medical Applications Expose Current Limits of AI

$swiper.update(), 300);},close() {this.isOpen = false;setTimeout(() => $swiper.update(), 300);}}" @keyup.escape="if (!$event.defaultPrevented) {$event.preventDefault();close();$focus($refs.toggle);}" @mousedown.outside="close()" :class="{'lg:w-4/12': isOpen,'md:w-5/12': isOpen,}">

EILMELDUNG —

__proto_headline__

EILMELDUNG —

__proto_headline__

Playing Doctor with Watson

Medical Applications Expose Current Limits of AI

IBM has big plans for how its Watson artificial intelligence software could change the medical industry. But a number of hospitals have ended their experiments with the platform, arguing that it doesn't help diagnose or treat diseases.

Von

Martin U. Müller

●

●

X.com

●

Facebook

●

E-Mail

●

Messenger

●

WhatsApp

●

●

●

E-Mail

●

Messenger

●

WhatsApp

●

image">

An ad for IBM's Watson computer at the Hannover Messe trade fair

Foto: DPA

You're in bad shape, very bad shape. And when you arrive at the office, you are faced with a choice: You can be treated by a senior physician who speaks soothingly, is the senior expert in his field and seems to have years of experience. "I've been working as a doctor for 35 years," he says. "We'll find out what's wrong with you."

Do you trust him?

Or would you go with the resident, who has been licensed for three months and has virtually no experience on the job? The young doctor holds a tablet computer under his arm. "It provides me with access to 600 years of experience from chief physicians," he says. "Don't worry, we'll find out what's wrong with you."

In fact, that's not an unrealistic scenario. According to an estimate made by German statutory health insurer AOK, nearly 20,000 people die every year in Germany alone as a result of malpractice. It can take up to half a decade for the correct diagnosis of rare diseases to be found, and in the best-case scenario, the average doctor has only studied around 1,000 out of 30,000 known diseases by the time of his or her final examinations.

This could all change with the help of data and artificial intelligence -- at least that's the promise currently being made in the global health-care industry. Machine medicine, the data-assisted diagnosis and treatment of diseases, is on the verge of revolutionizing medicine more deeply than stethoscopes did in 1816, X-rays in 1895 or cranial MRIs in 1978. It's even fueling a kind of euphoria in speeches, at conferences and in the media. Hopes are high, and so are the financial stakes.

No other company has been doing as much to advertise its work in the area as IBM. The company is a global leader in the IT industry, and with "Watson," it has created what it purports to be a true supercomputer.

Armed with 90 computer servers, Watson managed to defeat record-holders on the quiz show "Jeopardy" in 2011. Watson even helps edit movie trailers by filtering out the best scenes without human intervention. IBM markets Watson applications for rail transportation and defense lawyers.

With its miraculous new weapon, the software giant also wants to revolutionize medicine, a global market worth trillions of dollars, an industry in which hope and disappointment are closely linked. The prospects for the technology are considerable. The product aims to tackle much bigger conditions than colds, aches or pains -- like cancer or ailments with mysterious, unexplainable symptoms.

The approach used by Watson sounds logical: Given that medical knowledge is doubling every three years, no doctor out can keep up with all the research, and each patient can provide an extremely large amount of individual health data. Watson searches these data and findings for relevance to an individual case in ways that no doctor could.

At least in theory.

Failed Experiments

The program has been tested in Germany at university hospitals in Giessen and Marburg in the central German state of Hesse. Both campuses are quite happy to now have put the experiment behind them.

Put into practice, the system proved a lot less intelligent than hoped. At first, it stumbled over even the simplest of symptoms. If the doctor input that the patient was suffering from chest pain, the system didn't even include heart attack, angina pectoris or a torn aorta in its list of most likely diagnoses. Instead, Watson thought a rare infectious disease might be behind the symptoms. The Marburg doctors' experiences with Watson are now being widely discussed in the world of medicine. Some are even questioning whether Watson is more of a marketing bluff by IBM than a crowning achievement in the world of artificial intelligence.

Stephan Holzinger, the CEO of Rhön-Klinikum AG, which owns the university hospital, offers a sober take on Watson. When he became head of Germany's fourth-largest hospital operator in February 2017, he traveled to Marburg to take a closer look at the Watson project. "The performance was unacceptable -- the medical understanding at IBM just wasn't there," Holzinger says. "The company hadn't even fed the guidelines provided by the professional medical associations into the system. I thought to myself: If we continue with this, it will be like investing in a Las Vegas show." And it wasn't money that most concerned the CEO. "IBM acted as if it had reinvented medicine from scratch. In reality, they were all gloss and didn't have a plan. Our experts had to take them by the hand," he says.

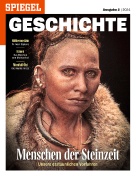

Graphic: How Watson is used

Foto: DER SPIEGEL

The executive terminated the project before it could be used by a single patient. Holzinger describes what then happened as follows: "IBM apparently saw us as an important showcase and worked with the people in charge at all levels."

For their part, officials at IBM speak of a "successful test" that has merely been ended.

In fact, the problems experienced with Watson in Marburg are a fundamental issue for IBM. One of the system's derided essential components is its language recognition, which is as essential as it is ín need of improvement. In Marburg, for example, patient documents, including letters from doctors and test results, were scanned. Watson searched them for keywords that might point to diagnoses or results.

Virtually all current software systems have difficulties with complex sentence structures. Negations, especially, are proving to be a real problem. A phrase like "could not be ruled out," which is used by doctors, is difficult for computer programs to interpret.

Doctors also have a penchant for writing in shorthand. This means that Watson must be trained to understand that "HR 75, SR, known BAV" stands for a normal heart rate of 75 and a known bicuspid aortic valve. Watson did relatively well after being taught, but complicated sentences remained a real challenge for IBM's software.

Not Ready for Prime Time

Watson isn't the only flawed medical assistance software. Other assistance systems, such as the Isabel Healthcare platform or Phenomizer, an online diagnostic system operated by Berlin's Charité university hospital, aren't producing perfect results either. IBM , however, has been trumpeting Watson's allegedly superior capabilities louder than the others.

What's more, the program fails to fulfill IBM's promises in its most important application: the treatment of cancer. People in this field have placed a great hope in supercomputers, because ever faster computers are making the decoding of the human genome more affordable. The greater the role genetics plays in the treatment of diseases, the more important such software will become -- because doctors quickly reach the limits of their capacities.

IBM says that's no problem for Watson. A patient's profile is entered into the supercomputer, which then searches all available medical science, including doctor's notes, clinical studies, guidelines, essays, medical records, case descriptions, signal paths and mutations. Once Watson has combed through all that data in the cloud, it provides treatment recommendations .

But even in oncology, some doctors quickly grew disappointed in the technology. "Watson couldn't even correctly identify common textbook treatments," says one doctor who used the system several times at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. "We had patients who came with Internet printouts or references to commercials on YouTube in the hope of finally having their cancer successfully treated by a computer," she says, describing the insane atmosphere that ensued. "A good intern can often provide people with better treatment suggestions than Watson can in its current form," she says.

Cancelled Projects

Starting in 2013, the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, even spent $60 million working with IBM's Watson before abandoning the project three years later. That decision had been preceded by a barrage of accusations of missed deadlines, mismanagement and that the system had been a waste of money. Venture capitalist Chamath Palihapitiya has described Watson as "a joke." He says Google and Amazon have made a lot more progress in terms of artificial intelligence. The German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg also decided not to renew its contract for a Watson project.

This presents not only an image problem for IBM, but also an economic one. Analysts at several institutions, including the investment bank Jefferies, have little faith in IBM when it comes to artificial intelligence. In the worst-case scenario, financial experts there say, the billions IBM has invested in the software may be a wash.

But officials at IBM believe Watson is on the path to success. "Watson for Oncology" is currently in use in more than 230 hospitals worldwide, compared to 150 a year ago, they say. The company also says an ever-growing number of scientific publications have noted the positive experiences doctors are having with Watson Health.

That's not surprising, either, given that cloud-based artificial intelligence represents a crucial part of the company's future business strategy. Over the next few years, IBM plans to invest billions of dollars in its health-care businesses. Only the financial industry is considered to be as bullish.

But the company's failure with Watson also raises some fundamental questions. How long will it take for artificial intelligence to become superior to the judgment of experienced doctors? And, more importantly: How can that be proven?

"There's a lot of anecdotal evidence of efficacy in digital medicine," says Martin Hirsch. The neuroscientist, who is working on the Ada medical app, says that classic scientific work in the sector is lacking. "We need studies," he says. "Good studies in which digital medicine must be compared with traditional treatments. And it is only at the point at which it is at least equally good that we should really be pushing for it."

A 'Very Charming' Idea

Tobias Gantner, a doctor and digital entrepreneur from Cologne, has a similar take. "Basically, the idea behind Watson -- of being able to peer into the future with the help of a lot of data -- is very charming," he says. "But I don't think that IBM's marketing really reflects reality. We need real data before we can get serious about using these systems."

Foto: DER SPIEGEL

The article you are reading originally appeared in German in issue 32/2018 (August 3rd, 2018) of DER SPIEGEL.

Frequently Asked Questions:

Everything You Need to Know about DER SPIEGEL

Six Decades of Quality Journalism:

The History of DER SPIEGEL

SPIEGEL Rights, Reprints and other Usages

This much is clear: Software programs like Watson have the potential to massively transform the ways hospitals and medical clinics are operated -- that is, if they at some point get better than actual doctors. But it's not as if the clinics are going to be left empty when artificial intelligence arrives. There's more to patient care, after all, than interpreting measured values, evaluating genetic material and combing through databases. It requires trust, discussions, comfort and sometimes just a pat on the back.

As Harvard cardiologist Bernard Lown, puts it: When all else fails, I just talk to the patient.

{setTimeout(() => resolve(false), this.CONSENT_INIT_TIMEOUT);$waitForConsent([$tcfv2Purposes.store_and_access_information_on_a_device]).then(() => resolve(true)).catch(() => resolve(false));});this.noAds = !consentForSpecificPurpose;}if (this.isInitialized) {return;}this.determinePartnerKey();this.determineOutbrainId();this.isInitialized = true;},determinePartnerKey() {if ($store.User.hasNoAdsAccess) {this.partnerKeyOutbrain = this.partnerKeysOutbrain['noAdsAccess'];return;}if (!$appUtils.isApp || !($appUtils.isAndroidApp || $appUtils.isIOSApp)) {return;}const device = $userAgentUtils.isTablet ? 'Tablet' : 'Mobile';this.partnerKeyOutbrain = this.partnerKeysOutbrain[`${$appUtils.appCode}${device}`];},determineOutbrainId() {const device = $appUtils.isApp ? $appUtils.appCode : 'web';const widgetsToFilter = $store.User.hasNoAdsAccess ? this.widgetIDs.noAdsAccess : this.widgetIDs.default;const widgetIds = Array.from(widgetsToFilter).filter((config) => {return ((typeof config.ads === 'undefined' || config.ads === !this.noAds)&& (typeof config.guaranteed === 'undefined' || config.guaranteed === this.guaranteed)&& (typeof config.type === 'undefined' || config.type === this.type)&& config.device === device) ? config.id : null;});this.outbrainId = (widgetIds[0] && widgetIds[0].id) ? widgetIds[0].id : null;if (this.outbrainId) {this.setTrackingReducedVersion();}},setTrackingReducedVersion() {if (!this.consentDisabled) return;const key = 'OB_ContextKeyValue';const value = 'notracking';if (!window[key]) {window[key] = value;}},}">

$publish('AD_POSITION_INIT', id));}">

Mehr lesen über

Medicine

Technology

Kostenlose Online-Spiele

mehr Spiele

Kreuzworträtsel

Kreuzworträtsel

Solitär

Solitär

Sudoku

Sudoku

Mahjong

Mahjong

Bubble-Shooter

Bubble-Shooter

Jackpot

Jackpot

Snake

Snake

Exchange

Exchange

2048

2048

Doppel

Doppel

Rushtower

Rushtower

Sudoken

Sudoken

Street

Street

Wortblitz

Wortblitz

Fibonacci

Fibonacci

Gumblast

Gumblast

Wimmelbild

Wimmelbild

Skiracer

Skiracer

Trivial Pursuit

Trivial Pursuit

Serviceangebote von SPIEGEL-Partnern

Gutscheine

Anzeige

Tchibo Gutscheine

Lampenwelt Gutscheine

OTTO Gutscheine

tink Gutscheine

Top Gutscheine

Alle Shops

●

Bußgeldrechner

●

Firmenwagenrechner

●

Brutto-Netto-Rechner

●

Jobsuche

●

Kurzarbeitergeld-Rechner

●

Studienfächer erklärt

●

Gehaltsvergleich

●

Versicherungen

●

Währungsrechner

●

Bücher bestellen

●

Eurojackpot

●

Ferientermine

●

GlücksSpirale

●

Gutscheine

●

LOTTO 6aus49

●

Seniorenportal

●

Spiele

●

Streaming Guide

●

Das tägliche Quiz

Alle Magazine des SPIEGEL

DER SPIEGEL

DER SPIEGEL

SPIEGEL BESTSELLER

SPIEGEL BESTSELLER

SPIEGEL SPEZIAL

SPIEGEL SPEZIAL

SPIEGEL GESCHICHTE

SPIEGEL GESCHICHTE

SPIEGEL WISSEN

SPIEGEL WISSEN

SPIEGEL COACHING

SPIEGEL COACHING

Dein SPIEGEL

Dein SPIEGEL

S-Magazin

S-Magazin

SPIEGEL CHRONIK

SPIEGEL CHRONIK

SPIEGEL Gruppe

Abo

Abo kündigen

Shop

manager magazin

Harvard Business manager

11FREUNDE

Werbung

Jobs

MANUFAKTUR

SPIEGEL Akademie

SPIEGEL Ed

Impressum

Datenschutz

Nutzungsbedingungen

Teilnahmebedingungen

Cookies & Tracking

Newsletter

Kontakt

Hilfe & Service

Text- & Nutzungsrechte

Facebook

Instagram

Wo Sie uns noch folgen können

{$data.initialX = event.touches[0].clientX;$data.initialY = event.touches[0].clientY;},onTouchMove: (event) => {if ($data.initialX === null || $data.initialY === null) {return;}const currentX = event.touches[0].clientX;const currentY = event.touches[0].clientY;const diffX = $data.initialX - currentX;const diffY = $data.initialY - currentY;const tolerance = 5;const yTolerance = (diffY > -Math.abs(tolerance)) && (diffY < Math.abs(tolerance))‥if (Math.abs(diffX) > Math.abs(diffY)) {$data.isOpen = !(diffX > 0 && yTolerance);}$data.initialX = null;$data.initialY = null;},}" x-subscribe.open_menu_drawer="isOpen = true;" @keyup.escape="if (!$event.defaultPrevented && isOpen) { $event.preventDefault(); isOpen = false; }" @touchstart.passive="onTouchStart($event)" @touchmove.passive="onTouchMove($event)">

●

Anmelden

●

Abonnement

●

Startseite

●

Schlagzeilen

●

Israel-Gaza-Krieg

●

Krieg in der Ukraine

●

Newsletter

●

Debatte

●

SPIEGEL+

●

Magazine

●

Meinung

●

Politik

●

Bundesregierung

●

Bundestag

●

Ausland

●

USA

●

Europa

●

Nahost

●

Globale Gesellschaft

●

Asien

●

Afrika

●

Panorama

n

●

Justiz & Kriminalität

●

Leute

●

Gesellschaft

●

Bildung

●

Sport

●

Ergebnisse & Tabellen

●

Liveticker

●

Fußball

●

Bundesliga

●

Champions League

●

Formel 1

●

Formel 1 – Liveticker, Kalender, WM-Stand

●

Wintersport

●

Wirtschaft

appen

●

Börse

●

Verbraucher & Service

●

Versicherungen

●

Unternehmen & Märkte

●

Staat & Soziales

●

Brutto-Netto-Rechner

●

Wissenschaft

ufklappen

●

Klimakrise

●

Mensch

●

Natur

●

Technik

●

Weltall

●

Medizin

●

Netzwelt

n

●

Netzpolitik

●

Web

●

Gadgets

●

Games

●

Apps

●

Kultur

●

Kino

●

Musik

●

TV

●

Literatur

●

SPIEGEL-Bestseller

●

Leben

●

Reise

●

Stil

●

Gesundheit

●

Familie

●

Psychologie

●

SPIEGEL Coaching

●

Reporter

●

Daten & Visualisierungen

●

Job & Karriere

●

Start

●

Geschichte

appen

●

Zeitzeugen

●

Erster Weltkrieg

●

Zweiter Weltkrieg

●

DDR

●

Film

●

Mobilität

pen

●

Fahrberichte

●

Fahrkultur

●

SPIEGEL in English

●

Dein SPIEGEL

●

Audio

●

Video

●

SPIEGEL-Events

●

Tests

●

Elektronik

●

Haushalt

●

Fahrrad & Zubehör

●

Küche

●

Camping

●

Garten

●

Auto-Zubehör

●

Brettspiele

●

Bestseller

●

Backstage

●

Themen

●

Vorteile mit S+

●

Marktplatz

Anzeige

z aufklappen

●

Jobsuche

●

Seniorenportal

●

Lotto

Anzeige

en

●

Eurojackpot

●

LOTTO 6aus49

●

GlücksSpirale

●

Gutscheine

Verlagsangebot

tscheine aufklappen

●

Adidas

●

Check24

●

Douglas

●

eBay

●

Expedia

●

H&M

●

Lidl

●

Lieferando

●

Otto

●

Saturn

●

Streaming Guide

Verlagsangebot

nü Streaming Guide aufklappen

●

Amazon Prime Video

●

Apple TV +

●

Disney+

●

MagentaTV

●

Netflix

●

Paramount+

●

WOW

●

Spiele

Verlagsangebot

aufklappen

●

Das tägliche Quiz

●

Kreuzworträtsel

●

Solitär

●

Sudoku

●

Mahjong

●

Snake

●

Jackpot

●

SPIEGEL-Heft

ufklappen

●

Heftarchiv

●

Shop

●

Alle Magazine

aufklappen

●

SPIEGEL WISSEN

●

Dein SPIEGEL

●

SPIEGEL GESCHICHTE

●

SPIEGEL EDITION

●

SPIEGEL LESEZEICHEN

●

SPIEGEL COACHING

●

SPIEGEL TV

●

RSS-Feed

●

SPIEGEL Media

aufklappen

●

MANUFAKTUR

●

Partner-Management

●

Sales Solutions

●

Programmatic Advertising

●

SPIEGEL Ed

●

SPIEGEL Akademie

●

Services

n

●

Bußgeldrechner

●

Ferientermine

●

Uni-Tools

●

Währungsrechner

●

Versicherungen

●

Nachrichtenarchiv

●

Facebook

●

Instagram

●

Wo Sie uns noch folgen können

onClipChanged())" x-if="isPlayerAttached">

isInitialized = true)" x-effect="document.documentElement.classList.toggle('audio-player-open', isOpen)" data-app-hidden data-area="audio-player">

Audio Player maximieren

Die Wiedergabe wurde unterbrochen.

playbackRate === $store.WebAudio.playbackRate);const nextIndex = (index + 1) % this.playbackRates.length;return this.playbackRates[nextIndex];}}" class="border font-bold font-sansUI h-24 px-6 rounded-oval text-xs border-sec2-dark dark:border-shade-lighter hover:border-sec2-darker dark:hover:border-shade-lightest text-sec2-dark dark:text-shade-lighter hover:text-sec2-darker dark:hover:text-shade-lightest" title="Wiedergabegeschwindigkeit ändern" @click="$publish('AUDIO_PLAYER_SET_PLAYBACK_RATE', nextPlaybackRate)" data-sara-click-el="button">

Wiedergabegeschwindigkeit ändern

or

0 ? $store.WebAudio.volume : this.lastVolume" class="md:hidden sm:hidden px-12 text-sec2-dark dark:text-shade-lighter hover:text-sec2-darker dark:hover:text-shade-lightest" :title="$store.WebAudio.volume === 0 ? 'Stummschaltung aufheben' : 'Stummschalten'" @click="$store.WebAudio.volume = $store.WebAudio.volume === 0 ? this.lastVolume : 0" data-sara-click-el="button">

Stummschalten

Stummschaltung aufheben

${type}`">

© Patrick Mariathasan / DER SPIEGEL

Anmelden oder Konto erstellen

An ad for IBM's Watson computer at the Hannover Messe trade fair

Foto: DPA

Graphic: How Watson is used

Foto: DER SPIEGEL

Helfen Sie uns, besser zu werden

© Patrick Mariathasan / DER SPIEGEL

Haben Sie einen Fehler im Text gefunden, auf den Sie uns hinweisen wollen? Oder gibt es ein technisches Problem? Melden Sie sich gern mit Ihrem Anliegen.

Redaktionellen Fehler melden

Technisches Problem melden

Sie haben weiteres inhaltliches Feedback oder eine Frage an uns?

Zum Kontaktformular

Mehrfachnutzung erkannt

Die gleichzeitige Nutzung von SPIEGEL+-Inhalten ist auf ein Gerät beschränkt.

Sie können SPIEGEL+ auf diesem Gerät weiterlesen oder sich abmelden, um Ihr Abo auf einem anderen Gerät zu nutzen.

Dieses Gerät abmelden

Sie möchten SPIEGEL+ auf mehreren Geräten zeitgleich nutzen?

Zu unseren Angeboten

![]()

__proto_headline__

__proto_description__

__proto_headline__

__proto_description__

An ad for IBM's Watson computer at the Hannover Messe trade fair

Foto: DPA

You're in bad shape, very bad shape. And when you arrive at the office, you are faced with a choice: You can be treated by a senior physician who speaks soothingly, is the senior expert in his field and seems to have years of experience. "I've been working as a doctor for 35 years," he says. "We'll find out what's wrong with you."

Do you trust him?

Or would you go with the resident, who has been licensed for three months and has virtually no experience on the job? The young doctor holds a tablet computer under his arm. "It provides me with access to 600 years of experience from chief physicians," he says. "Don't worry, we'll find out what's wrong with you."

In fact, that's not an unrealistic scenario. According to an estimate made by German statutory health insurer AOK, nearly 20,000 people die every year in Germany alone as a result of malpractice. It can take up to half a decade for the correct diagnosis of rare diseases to be found, and in the best-case scenario, the average doctor has only studied around 1,000 out of 30,000 known diseases by the time of his or her final examinations.

This could all change with the help of data and artificial intelligence -- at least that's the promise currently being made in the global health-care industry. Machine medicine, the data-assisted diagnosis and treatment of diseases, is on the verge of revolutionizing medicine more deeply than stethoscopes did in 1816, X-rays in 1895 or cranial MRIs in 1978. It's even fueling a kind of euphoria in speeches, at conferences and in the media. Hopes are high, and so are the financial stakes.

No other company has been doing as much to advertise its work in the area as IBM. The company is a global leader in the IT industry, and with "Watson," it has created what it purports to be a true supercomputer.

Armed with 90 computer servers, Watson managed to defeat record-holders on the quiz show "Jeopardy" in 2011. Watson even helps edit movie trailers by filtering out the best scenes without human intervention. IBM markets Watson applications for rail transportation and defense lawyers.

With its miraculous new weapon, the software giant also wants to revolutionize medicine, a global market worth trillions of dollars, an industry in which hope and disappointment are closely linked. The prospects for the technology are considerable. The product aims to tackle much bigger conditions than colds, aches or pains -- like cancer or ailments with mysterious, unexplainable symptoms.

The approach used by Watson sounds logical: Given that medical knowledge is doubling every three years, no doctor out can keep up with all the research, and each patient can provide an extremely large amount of individual health data. Watson searches these data and findings for relevance to an individual case in ways that no doctor could.

At least in theory.

Failed Experiments

The program has been tested in Germany at university hospitals in Giessen and Marburg in the central German state of Hesse. Both campuses are quite happy to now have put the experiment behind them.

Put into practice, the system proved a lot less intelligent than hoped. At first, it stumbled over even the simplest of symptoms. If the doctor input that the patient was suffering from chest pain, the system didn't even include heart attack, angina pectoris or a torn aorta in its list of most likely diagnoses. Instead, Watson thought a rare infectious disease might be behind the symptoms. The Marburg doctors' experiences with Watson are now being widely discussed in the world of medicine. Some are even questioning whether Watson is more of a marketing bluff by IBM than a crowning achievement in the world of artificial intelligence.

Stephan Holzinger, the CEO of Rhön-Klinikum AG, which owns the university hospital, offers a sober take on Watson. When he became head of Germany's fourth-largest hospital operator in February 2017, he traveled to Marburg to take a closer look at the Watson project. "The performance was unacceptable -- the medical understanding at IBM just wasn't there," Holzinger says. "The company hadn't even fed the guidelines provided by the professional medical associations into the system. I thought to myself: If we continue with this, it will be like investing in a Las Vegas show." And it wasn't money that most concerned the CEO. "IBM acted as if it had reinvented medicine from scratch. In reality, they were all gloss and didn't have a plan. Our experts had to take them by the hand," he says.

An ad for IBM's Watson computer at the Hannover Messe trade fair

Foto: DPA

You're in bad shape, very bad shape. And when you arrive at the office, you are faced with a choice: You can be treated by a senior physician who speaks soothingly, is the senior expert in his field and seems to have years of experience. "I've been working as a doctor for 35 years," he says. "We'll find out what's wrong with you."

Do you trust him?

Or would you go with the resident, who has been licensed for three months and has virtually no experience on the job? The young doctor holds a tablet computer under his arm. "It provides me with access to 600 years of experience from chief physicians," he says. "Don't worry, we'll find out what's wrong with you."

In fact, that's not an unrealistic scenario. According to an estimate made by German statutory health insurer AOK, nearly 20,000 people die every year in Germany alone as a result of malpractice. It can take up to half a decade for the correct diagnosis of rare diseases to be found, and in the best-case scenario, the average doctor has only studied around 1,000 out of 30,000 known diseases by the time of his or her final examinations.

This could all change with the help of data and artificial intelligence -- at least that's the promise currently being made in the global health-care industry. Machine medicine, the data-assisted diagnosis and treatment of diseases, is on the verge of revolutionizing medicine more deeply than stethoscopes did in 1816, X-rays in 1895 or cranial MRIs in 1978. It's even fueling a kind of euphoria in speeches, at conferences and in the media. Hopes are high, and so are the financial stakes.

No other company has been doing as much to advertise its work in the area as IBM. The company is a global leader in the IT industry, and with "Watson," it has created what it purports to be a true supercomputer.

Armed with 90 computer servers, Watson managed to defeat record-holders on the quiz show "Jeopardy" in 2011. Watson even helps edit movie trailers by filtering out the best scenes without human intervention. IBM markets Watson applications for rail transportation and defense lawyers.

With its miraculous new weapon, the software giant also wants to revolutionize medicine, a global market worth trillions of dollars, an industry in which hope and disappointment are closely linked. The prospects for the technology are considerable. The product aims to tackle much bigger conditions than colds, aches or pains -- like cancer or ailments with mysterious, unexplainable symptoms.

The approach used by Watson sounds logical: Given that medical knowledge is doubling every three years, no doctor out can keep up with all the research, and each patient can provide an extremely large amount of individual health data. Watson searches these data and findings for relevance to an individual case in ways that no doctor could.

At least in theory.

Failed Experiments

The program has been tested in Germany at university hospitals in Giessen and Marburg in the central German state of Hesse. Both campuses are quite happy to now have put the experiment behind them.

Put into practice, the system proved a lot less intelligent than hoped. At first, it stumbled over even the simplest of symptoms. If the doctor input that the patient was suffering from chest pain, the system didn't even include heart attack, angina pectoris or a torn aorta in its list of most likely diagnoses. Instead, Watson thought a rare infectious disease might be behind the symptoms. The Marburg doctors' experiences with Watson are now being widely discussed in the world of medicine. Some are even questioning whether Watson is more of a marketing bluff by IBM than a crowning achievement in the world of artificial intelligence.

Stephan Holzinger, the CEO of Rhön-Klinikum AG, which owns the university hospital, offers a sober take on Watson. When he became head of Germany's fourth-largest hospital operator in February 2017, he traveled to Marburg to take a closer look at the Watson project. "The performance was unacceptable -- the medical understanding at IBM just wasn't there," Holzinger says. "The company hadn't even fed the guidelines provided by the professional medical associations into the system. I thought to myself: If we continue with this, it will be like investing in a Las Vegas show." And it wasn't money that most concerned the CEO. "IBM acted as if it had reinvented medicine from scratch. In reality, they were all gloss and didn't have a plan. Our experts had to take them by the hand," he says.

Graphic: How Watson is used

Foto: DER SPIEGEL

The executive terminated the project before it could be used by a single patient. Holzinger describes what then happened as follows: "IBM apparently saw us as an important showcase and worked with the people in charge at all levels."

For their part, officials at IBM speak of a "successful test" that has merely been ended.

In fact, the problems experienced with Watson in Marburg are a fundamental issue for IBM. One of the system's derided essential components is its language recognition, which is as essential as it is ín need of improvement. In Marburg, for example, patient documents, including letters from doctors and test results, were scanned. Watson searched them for keywords that might point to diagnoses or results.

Virtually all current software systems have difficulties with complex sentence structures. Negations, especially, are proving to be a real problem. A phrase like "could not be ruled out," which is used by doctors, is difficult for computer programs to interpret.

Doctors also have a penchant for writing in shorthand. This means that Watson must be trained to understand that "HR 75, SR, known BAV" stands for a normal heart rate of 75 and a known bicuspid aortic valve. Watson did relatively well after being taught, but complicated sentences remained a real challenge for IBM's software.

Not Ready for Prime Time

Watson isn't the only flawed medical assistance software. Other assistance systems, such as the Isabel Healthcare platform or Phenomizer, an online diagnostic system operated by Berlin's Charité university hospital, aren't producing perfect results either. IBM , however, has been trumpeting Watson's allegedly superior capabilities louder than the others.

What's more, the program fails to fulfill IBM's promises in its most important application: the treatment of cancer. People in this field have placed a great hope in supercomputers, because ever faster computers are making the decoding of the human genome more affordable. The greater the role genetics plays in the treatment of diseases, the more important such software will become -- because doctors quickly reach the limits of their capacities.

IBM says that's no problem for Watson. A patient's profile is entered into the supercomputer, which then searches all available medical science, including doctor's notes, clinical studies, guidelines, essays, medical records, case descriptions, signal paths and mutations. Once Watson has combed through all that data in the cloud, it provides treatment recommendations .

But even in oncology, some doctors quickly grew disappointed in the technology. "Watson couldn't even correctly identify common textbook treatments," says one doctor who used the system several times at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. "We had patients who came with Internet printouts or references to commercials on YouTube in the hope of finally having their cancer successfully treated by a computer," she says, describing the insane atmosphere that ensued. "A good intern can often provide people with better treatment suggestions than Watson can in its current form," she says.

Cancelled Projects

Starting in 2013, the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, even spent $60 million working with IBM's Watson before abandoning the project three years later. That decision had been preceded by a barrage of accusations of missed deadlines, mismanagement and that the system had been a waste of money. Venture capitalist Chamath Palihapitiya has described Watson as "a joke." He says Google and Amazon have made a lot more progress in terms of artificial intelligence. The German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg also decided not to renew its contract for a Watson project.

This presents not only an image problem for IBM, but also an economic one. Analysts at several institutions, including the investment bank Jefferies, have little faith in IBM when it comes to artificial intelligence. In the worst-case scenario, financial experts there say, the billions IBM has invested in the software may be a wash.

But officials at IBM believe Watson is on the path to success. "Watson for Oncology" is currently in use in more than 230 hospitals worldwide, compared to 150 a year ago, they say. The company also says an ever-growing number of scientific publications have noted the positive experiences doctors are having with Watson Health.

That's not surprising, either, given that cloud-based artificial intelligence represents a crucial part of the company's future business strategy. Over the next few years, IBM plans to invest billions of dollars in its health-care businesses. Only the financial industry is considered to be as bullish.

But the company's failure with Watson also raises some fundamental questions. How long will it take for artificial intelligence to become superior to the judgment of experienced doctors? And, more importantly: How can that be proven?

"There's a lot of anecdotal evidence of efficacy in digital medicine," says Martin Hirsch. The neuroscientist, who is working on the Ada medical app, says that classic scientific work in the sector is lacking. "We need studies," he says. "Good studies in which digital medicine must be compared with traditional treatments. And it is only at the point at which it is at least equally good that we should really be pushing for it."

A 'Very Charming' Idea

Tobias Gantner, a doctor and digital entrepreneur from Cologne, has a similar take. "Basically, the idea behind Watson -- of being able to peer into the future with the help of a lot of data -- is very charming," he says. "But I don't think that IBM's marketing really reflects reality. We need real data before we can get serious about using these systems."

Graphic: How Watson is used

Foto: DER SPIEGEL

The executive terminated the project before it could be used by a single patient. Holzinger describes what then happened as follows: "IBM apparently saw us as an important showcase and worked with the people in charge at all levels."

For their part, officials at IBM speak of a "successful test" that has merely been ended.

In fact, the problems experienced with Watson in Marburg are a fundamental issue for IBM. One of the system's derided essential components is its language recognition, which is as essential as it is ín need of improvement. In Marburg, for example, patient documents, including letters from doctors and test results, were scanned. Watson searched them for keywords that might point to diagnoses or results.

Virtually all current software systems have difficulties with complex sentence structures. Negations, especially, are proving to be a real problem. A phrase like "could not be ruled out," which is used by doctors, is difficult for computer programs to interpret.

Doctors also have a penchant for writing in shorthand. This means that Watson must be trained to understand that "HR 75, SR, known BAV" stands for a normal heart rate of 75 and a known bicuspid aortic valve. Watson did relatively well after being taught, but complicated sentences remained a real challenge for IBM's software.

Not Ready for Prime Time

Watson isn't the only flawed medical assistance software. Other assistance systems, such as the Isabel Healthcare platform or Phenomizer, an online diagnostic system operated by Berlin's Charité university hospital, aren't producing perfect results either. IBM , however, has been trumpeting Watson's allegedly superior capabilities louder than the others.

What's more, the program fails to fulfill IBM's promises in its most important application: the treatment of cancer. People in this field have placed a great hope in supercomputers, because ever faster computers are making the decoding of the human genome more affordable. The greater the role genetics plays in the treatment of diseases, the more important such software will become -- because doctors quickly reach the limits of their capacities.

IBM says that's no problem for Watson. A patient's profile is entered into the supercomputer, which then searches all available medical science, including doctor's notes, clinical studies, guidelines, essays, medical records, case descriptions, signal paths and mutations. Once Watson has combed through all that data in the cloud, it provides treatment recommendations .

But even in oncology, some doctors quickly grew disappointed in the technology. "Watson couldn't even correctly identify common textbook treatments," says one doctor who used the system several times at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York. "We had patients who came with Internet printouts or references to commercials on YouTube in the hope of finally having their cancer successfully treated by a computer," she says, describing the insane atmosphere that ensued. "A good intern can often provide people with better treatment suggestions than Watson can in its current form," she says.

Cancelled Projects

Starting in 2013, the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, even spent $60 million working with IBM's Watson before abandoning the project three years later. That decision had been preceded by a barrage of accusations of missed deadlines, mismanagement and that the system had been a waste of money. Venture capitalist Chamath Palihapitiya has described Watson as "a joke." He says Google and Amazon have made a lot more progress in terms of artificial intelligence. The German Cancer Research Center in Heidelberg also decided not to renew its contract for a Watson project.

This presents not only an image problem for IBM, but also an economic one. Analysts at several institutions, including the investment bank Jefferies, have little faith in IBM when it comes to artificial intelligence. In the worst-case scenario, financial experts there say, the billions IBM has invested in the software may be a wash.

But officials at IBM believe Watson is on the path to success. "Watson for Oncology" is currently in use in more than 230 hospitals worldwide, compared to 150 a year ago, they say. The company also says an ever-growing number of scientific publications have noted the positive experiences doctors are having with Watson Health.

That's not surprising, either, given that cloud-based artificial intelligence represents a crucial part of the company's future business strategy. Over the next few years, IBM plans to invest billions of dollars in its health-care businesses. Only the financial industry is considered to be as bullish.

But the company's failure with Watson also raises some fundamental questions. How long will it take for artificial intelligence to become superior to the judgment of experienced doctors? And, more importantly: How can that be proven?

"There's a lot of anecdotal evidence of efficacy in digital medicine," says Martin Hirsch. The neuroscientist, who is working on the Ada medical app, says that classic scientific work in the sector is lacking. "We need studies," he says. "Good studies in which digital medicine must be compared with traditional treatments. And it is only at the point at which it is at least equally good that we should really be pushing for it."

A 'Very Charming' Idea

Tobias Gantner, a doctor and digital entrepreneur from Cologne, has a similar take. "Basically, the idea behind Watson -- of being able to peer into the future with the help of a lot of data -- is very charming," he says. "But I don't think that IBM's marketing really reflects reality. We need real data before we can get serious about using these systems."

Six Decades of Quality Journalism:

The History of DER SPIEGEL

Six Decades of Quality Journalism:

The History of DER SPIEGEL

SPIEGEL Rights, Reprints and other Usages

SPIEGEL Rights, Reprints and other Usages

This much is clear: Software programs like Watson have the potential to massively transform the ways hospitals and medical clinics are operated -- that is, if they at some point get better than actual doctors. But it's not as if the clinics are going to be left empty when artificial intelligence arrives. There's more to patient care, after all, than interpreting measured values, evaluating genetic material and combing through databases. It requires trust, discussions, comfort and sometimes just a pat on the back.

As Harvard cardiologist Bernard Lown, puts it: When all else fails, I just talk to the patient.

{setTimeout(() => resolve(false), this.CONSENT_INIT_TIMEOUT);$waitForConsent([$tcfv2Purposes.store_and_access_information_on_a_device]).then(() => resolve(true)).catch(() => resolve(false));});this.noAds = !consentForSpecificPurpose;}if (this.isInitialized) {return;}this.determinePartnerKey();this.determineOutbrainId();this.isInitialized = true;},determinePartnerKey() {if ($store.User.hasNoAdsAccess) {this.partnerKeyOutbrain = this.partnerKeysOutbrain['noAdsAccess'];return;}if (!$appUtils.isApp || !($appUtils.isAndroidApp || $appUtils.isIOSApp)) {return;}const device = $userAgentUtils.isTablet ? 'Tablet' : 'Mobile';this.partnerKeyOutbrain = this.partnerKeysOutbrain[`${$appUtils.appCode}${device}`];},determineOutbrainId() {const device = $appUtils.isApp ? $appUtils.appCode : 'web';const widgetsToFilter = $store.User.hasNoAdsAccess ? this.widgetIDs.noAdsAccess : this.widgetIDs.default;const widgetIds = Array.from(widgetsToFilter).filter((config) => {return ((typeof config.ads === 'undefined' || config.ads === !this.noAds)&& (typeof config.guaranteed === 'undefined' || config.guaranteed === this.guaranteed)&& (typeof config.type === 'undefined' || config.type === this.type)&& config.device === device) ? config.id : null;});this.outbrainId = (widgetIds[0] && widgetIds[0].id) ? widgetIds[0].id : null;if (this.outbrainId) {this.setTrackingReducedVersion();}},setTrackingReducedVersion() {if (!this.consentDisabled) return;const key = 'OB_ContextKeyValue';const value = 'notracking';if (!window[key]) {window[key] = value;}},}">

$publish('AD_POSITION_INIT', id));}">

This much is clear: Software programs like Watson have the potential to massively transform the ways hospitals and medical clinics are operated -- that is, if they at some point get better than actual doctors. But it's not as if the clinics are going to be left empty when artificial intelligence arrives. There's more to patient care, after all, than interpreting measured values, evaluating genetic material and combing through databases. It requires trust, discussions, comfort and sometimes just a pat on the back.

As Harvard cardiologist Bernard Lown, puts it: When all else fails, I just talk to the patient.

{setTimeout(() => resolve(false), this.CONSENT_INIT_TIMEOUT);$waitForConsent([$tcfv2Purposes.store_and_access_information_on_a_device]).then(() => resolve(true)).catch(() => resolve(false));});this.noAds = !consentForSpecificPurpose;}if (this.isInitialized) {return;}this.determinePartnerKey();this.determineOutbrainId();this.isInitialized = true;},determinePartnerKey() {if ($store.User.hasNoAdsAccess) {this.partnerKeyOutbrain = this.partnerKeysOutbrain['noAdsAccess'];return;}if (!$appUtils.isApp || !($appUtils.isAndroidApp || $appUtils.isIOSApp)) {return;}const device = $userAgentUtils.isTablet ? 'Tablet' : 'Mobile';this.partnerKeyOutbrain = this.partnerKeysOutbrain[`${$appUtils.appCode}${device}`];},determineOutbrainId() {const device = $appUtils.isApp ? $appUtils.appCode : 'web';const widgetsToFilter = $store.User.hasNoAdsAccess ? this.widgetIDs.noAdsAccess : this.widgetIDs.default;const widgetIds = Array.from(widgetsToFilter).filter((config) => {return ((typeof config.ads === 'undefined' || config.ads === !this.noAds)&& (typeof config.guaranteed === 'undefined' || config.guaranteed === this.guaranteed)&& (typeof config.type === 'undefined' || config.type === this.type)&& config.device === device) ? config.id : null;});this.outbrainId = (widgetIds[0] && widgetIds[0].id) ? widgetIds[0].id : null;if (this.outbrainId) {this.setTrackingReducedVersion();}},setTrackingReducedVersion() {if (!this.consentDisabled) return;const key = 'OB_ContextKeyValue';const value = 'notracking';if (!window[key]) {window[key] = value;}},}">

$publish('AD_POSITION_INIT', id));}">

DER SPIEGEL

DER SPIEGEL

SPIEGEL BESTSELLER

SPIEGEL BESTSELLER

SPIEGEL SPEZIAL

SPIEGEL SPEZIAL

SPIEGEL GESCHICHTE

SPIEGEL GESCHICHTE

SPIEGEL WISSEN

SPIEGEL WISSEN

SPIEGEL COACHING

SPIEGEL COACHING

Dein SPIEGEL

Dein SPIEGEL

S-Magazin

S-Magazin

SPIEGEL CHRONIK

SPIEGEL Gruppe

Abo

Abo kündigen

Shop

manager magazin

Harvard Business manager

11FREUNDE

Werbung

Jobs

MANUFAKTUR

SPIEGEL Akademie

SPIEGEL Ed

Impressum

Datenschutz

Nutzungsbedingungen

Teilnahmebedingungen

Cookies & Tracking

Newsletter

Kontakt

Hilfe & Service

Text- & Nutzungsrechte

Facebook

Instagram

Wo Sie uns noch folgen können

{$data.initialX = event.touches[0].clientX;$data.initialY = event.touches[0].clientY;},onTouchMove: (event) => {if ($data.initialX === null || $data.initialY === null) {return;}const currentX = event.touches[0].clientX;const currentY = event.touches[0].clientY;const diffX = $data.initialX - currentX;const diffY = $data.initialY - currentY;const tolerance = 5;const yTolerance = (diffY > -Math.abs(tolerance)) && (diffY < Math.abs(tolerance))‥if (Math.abs(diffX) > Math.abs(diffY)) {$data.isOpen = !(diffX > 0 && yTolerance);}$data.initialX = null;$data.initialY = null;},}" x-subscribe.open_menu_drawer="isOpen = true;" @keyup.escape="if (!$event.defaultPrevented && isOpen) { $event.preventDefault(); isOpen = false; }" @touchstart.passive="onTouchStart($event)" @touchmove.passive="onTouchMove($event)">

●

Anmelden

●

Abonnement

●

Startseite

●

Schlagzeilen

●

Israel-Gaza-Krieg

●

Krieg in der Ukraine

●

Newsletter

●

Debatte

●

SPIEGEL+

●

Magazine

●

Meinung

●

Politik

●

Bundesregierung

●

Bundestag

●

Ausland

●

USA

●

Europa

●

Nahost

●

Globale Gesellschaft

●

Asien

●

Afrika

●

Panorama

n

●

Justiz & Kriminalität

●

Leute

●

Gesellschaft

●

Bildung

●

Sport

●

Ergebnisse & Tabellen

●

Liveticker

●

Fußball

●

Bundesliga

●

Champions League

●

Formel 1

●

Formel 1 – Liveticker, Kalender, WM-Stand

●

Wintersport

●

Wirtschaft

appen

●

Börse

●

Verbraucher & Service

●

Versicherungen

●

Unternehmen & Märkte

●

Staat & Soziales

●

Brutto-Netto-Rechner

●

Wissenschaft

ufklappen

●

Klimakrise

●

Mensch

●

Natur

●

Technik

●

Weltall

●

Medizin

●

Netzwelt

n

●

Netzpolitik

●

Web

●

Gadgets

●

Games

●

Apps

●

Kultur

●

Kino

●

Musik

●

TV

●

Literatur

●

SPIEGEL-Bestseller

●

Leben

●

Reise

●

Stil

●

Gesundheit

●

Familie

●

Psychologie

●

SPIEGEL Coaching

●

Reporter

●

Daten & Visualisierungen

●

Job & Karriere

●

Start

●

Geschichte

appen

●

Zeitzeugen

●

Erster Weltkrieg

●

Zweiter Weltkrieg

●

DDR

●

Film

●

Mobilität

pen

●

Fahrberichte

●

Fahrkultur

●

SPIEGEL in English

●

Dein SPIEGEL

●

Audio

●

Video

●

SPIEGEL-Events

●

Tests

●

Elektronik

●

Haushalt

●

Fahrrad & Zubehör

●

Küche

●

Camping

●

Garten

●

Auto-Zubehör

●

Brettspiele

●

Bestseller

●

Backstage

●

Themen

●

Vorteile mit S+

●

Marktplatz

Anzeige

z aufklappen

●

Jobsuche

●

Seniorenportal

●

Lotto

Anzeige

en

●

Eurojackpot

●

LOTTO 6aus49

●

GlücksSpirale

●

Gutscheine

Verlagsangebot

tscheine aufklappen

●

Adidas

●

Check24

●

Douglas

●

eBay

●

Expedia

●

H&M

●

Lidl

●

Lieferando

●

Otto

●

Saturn

●

Streaming Guide

Verlagsangebot

nü Streaming Guide aufklappen

●

Amazon Prime Video

●

Apple TV +

●

Disney+

●

MagentaTV

●

Netflix

●

Paramount+

●

WOW

●

Spiele

Verlagsangebot

aufklappen

●

Das tägliche Quiz

●

Kreuzworträtsel

●

Solitär

●

Sudoku

●

Mahjong

●

Snake

●

Jackpot

●

SPIEGEL-Heft

ufklappen

●

Heftarchiv

●

Shop

●

Alle Magazine

aufklappen

●

SPIEGEL WISSEN

●

Dein SPIEGEL

●

SPIEGEL GESCHICHTE

●

SPIEGEL EDITION

●

SPIEGEL LESEZEICHEN

●

SPIEGEL COACHING

●

SPIEGEL TV

●

RSS-Feed

●

SPIEGEL Media

aufklappen

●

MANUFAKTUR

●

Partner-Management

●

Sales Solutions

●

Programmatic Advertising

●

SPIEGEL Ed

●

SPIEGEL Akademie

●

Services

n

●

Bußgeldrechner

●

Ferientermine

●

Uni-Tools

●

Währungsrechner

●

Versicherungen

●

Nachrichtenarchiv

●

Facebook

●

Instagram

●

Wo Sie uns noch folgen können

onClipChanged())" x-if="isPlayerAttached">

isInitialized = true)" x-effect="document.documentElement.classList.toggle('audio-player-open', isOpen)" data-app-hidden data-area="audio-player">

Audio Player maximieren

Die Wiedergabe wurde unterbrochen.

SPIEGEL CHRONIK

SPIEGEL Gruppe

Abo

Abo kündigen

Shop

manager magazin

Harvard Business manager

11FREUNDE

Werbung

Jobs

MANUFAKTUR

SPIEGEL Akademie

SPIEGEL Ed

Impressum

Datenschutz

Nutzungsbedingungen

Teilnahmebedingungen

Cookies & Tracking

Newsletter

Kontakt

Hilfe & Service

Text- & Nutzungsrechte

Facebook

Instagram

Wo Sie uns noch folgen können

{$data.initialX = event.touches[0].clientX;$data.initialY = event.touches[0].clientY;},onTouchMove: (event) => {if ($data.initialX === null || $data.initialY === null) {return;}const currentX = event.touches[0].clientX;const currentY = event.touches[0].clientY;const diffX = $data.initialX - currentX;const diffY = $data.initialY - currentY;const tolerance = 5;const yTolerance = (diffY > -Math.abs(tolerance)) && (diffY < Math.abs(tolerance))‥if (Math.abs(diffX) > Math.abs(diffY)) {$data.isOpen = !(diffX > 0 && yTolerance);}$data.initialX = null;$data.initialY = null;},}" x-subscribe.open_menu_drawer="isOpen = true;" @keyup.escape="if (!$event.defaultPrevented && isOpen) { $event.preventDefault(); isOpen = false; }" @touchstart.passive="onTouchStart($event)" @touchmove.passive="onTouchMove($event)">

●

Anmelden

●

Abonnement

●

Startseite

●

Schlagzeilen

●

Israel-Gaza-Krieg

●

Krieg in der Ukraine

●

Newsletter

●

Debatte

●

SPIEGEL+

●

Magazine

●

Meinung

●

Politik

●

Bundesregierung

●

Bundestag

●

Ausland

●

USA

●

Europa

●

Nahost

●

Globale Gesellschaft

●

Asien

●

Afrika

●

Panorama

n

●

Justiz & Kriminalität

●

Leute

●

Gesellschaft

●

Bildung

●

Sport

●

Ergebnisse & Tabellen

●

Liveticker

●

Fußball

●

Bundesliga

●

Champions League

●

Formel 1

●

Formel 1 – Liveticker, Kalender, WM-Stand

●

Wintersport

●

Wirtschaft

appen

●

Börse

●

Verbraucher & Service

●

Versicherungen

●

Unternehmen & Märkte

●

Staat & Soziales

●

Brutto-Netto-Rechner

●

Wissenschaft

ufklappen

●

Klimakrise

●

Mensch

●

Natur

●

Technik

●

Weltall

●

Medizin

●

Netzwelt

n

●

Netzpolitik

●

Web

●

Gadgets

●

Games

●

Apps

●

Kultur

●

Kino

●

Musik

●

TV

●

Literatur

●

SPIEGEL-Bestseller

●

Leben

●

Reise

●

Stil

●

Gesundheit

●

Familie

●

Psychologie

●

SPIEGEL Coaching

●

Reporter

●

Daten & Visualisierungen

●

Job & Karriere

●

Start

●

Geschichte

appen

●

Zeitzeugen

●

Erster Weltkrieg

●

Zweiter Weltkrieg

●

DDR

●

Film

●

Mobilität

pen

●

Fahrberichte

●

Fahrkultur

●

SPIEGEL in English

●

Dein SPIEGEL

●

Audio

●

Video

●

SPIEGEL-Events

●

Tests

●

Elektronik

●

Haushalt

●

Fahrrad & Zubehör

●

Küche

●

Camping

●

Garten

●

Auto-Zubehör

●

Brettspiele

●

Bestseller

●

Backstage

●

Themen

●

Vorteile mit S+

●

Marktplatz

Anzeige

z aufklappen

●

Jobsuche

●

Seniorenportal

●

Lotto

Anzeige

en

●

Eurojackpot

●

LOTTO 6aus49

●

GlücksSpirale

●

Gutscheine

Verlagsangebot

tscheine aufklappen

●

Adidas

●

Check24

●

Douglas

●

eBay

●

Expedia

●

H&M

●

Lidl

●

Lieferando

●

Otto

●

Saturn

●

Streaming Guide

Verlagsangebot

nü Streaming Guide aufklappen

●

Amazon Prime Video

●

Apple TV +

●

Disney+

●

MagentaTV

●

Netflix

●

Paramount+

●

WOW

●

Spiele

Verlagsangebot

aufklappen

●

Das tägliche Quiz

●

Kreuzworträtsel

●

Solitär

●

Sudoku

●

Mahjong

●

Snake

●

Jackpot

●

SPIEGEL-Heft

ufklappen

●

Heftarchiv

●

Shop

●

Alle Magazine

aufklappen

●

SPIEGEL WISSEN

●

Dein SPIEGEL

●

SPIEGEL GESCHICHTE

●

SPIEGEL EDITION

●

SPIEGEL LESEZEICHEN

●

SPIEGEL COACHING

●

SPIEGEL TV

●

RSS-Feed

●

SPIEGEL Media

aufklappen

●

MANUFAKTUR

●

Partner-Management

●

Sales Solutions

●

Programmatic Advertising

●

SPIEGEL Ed

●

SPIEGEL Akademie

●

Services

n

●

Bußgeldrechner

●

Ferientermine

●

Uni-Tools

●

Währungsrechner

●

Versicherungen

●

Nachrichtenarchiv

●

Facebook

●

Instagram

●

Wo Sie uns noch folgen können

onClipChanged())" x-if="isPlayerAttached">

isInitialized = true)" x-effect="document.documentElement.classList.toggle('audio-player-open', isOpen)" data-app-hidden data-area="audio-player">

Audio Player maximieren

Die Wiedergabe wurde unterbrochen.

An ad for IBM's Watson computer at the Hannover Messe trade fair

Foto: DPA

An ad for IBM's Watson computer at the Hannover Messe trade fair

Foto: DPA

Graphic: How Watson is used

Foto: DER SPIEGEL

Helfen Sie uns, besser zu werden

Graphic: How Watson is used

Foto: DER SPIEGEL

Helfen Sie uns, besser zu werden

© Patrick Mariathasan / DER SPIEGEL

Haben Sie einen Fehler im Text gefunden, auf den Sie uns hinweisen wollen? Oder gibt es ein technisches Problem? Melden Sie sich gern mit Ihrem Anliegen.

Redaktionellen Fehler melden

Technisches Problem melden

Sie haben weiteres inhaltliches Feedback oder eine Frage an uns?

Zum Kontaktformular

Mehrfachnutzung erkannt

© Patrick Mariathasan / DER SPIEGEL

Haben Sie einen Fehler im Text gefunden, auf den Sie uns hinweisen wollen? Oder gibt es ein technisches Problem? Melden Sie sich gern mit Ihrem Anliegen.

Redaktionellen Fehler melden

Technisches Problem melden

Sie haben weiteres inhaltliches Feedback oder eine Frage an uns?

Zum Kontaktformular

Mehrfachnutzung erkannt

Die gleichzeitige Nutzung von SPIEGEL+-Inhalten ist auf ein Gerät beschränkt.

Sie können SPIEGEL+ auf diesem Gerät weiterlesen oder sich abmelden, um Ihr Abo auf einem anderen Gerät zu nutzen.

Dieses Gerät abmelden

Sie möchten SPIEGEL+ auf mehreren Geräten zeitgleich nutzen?

Zu unseren Angeboten

Die gleichzeitige Nutzung von SPIEGEL+-Inhalten ist auf ein Gerät beschränkt.

Sie können SPIEGEL+ auf diesem Gerät weiterlesen oder sich abmelden, um Ihr Abo auf einem anderen Gerät zu nutzen.

Dieses Gerät abmelden

Sie möchten SPIEGEL+ auf mehreren Geräten zeitgleich nutzen?

Zu unseren Angeboten