Aaron Siskind (December 4, 1903 – February 8, 1991) was an American photographer whose work focuses on the details of things, presented as flat surfaces[1] to create a new image independent of the original subject. He was closely involved with, if not a part of, the abstract expressionist movement, and was close friends with painters Franz Kline (whose own breakthrough show at the Charles Egan Gallery occurred in the same period as Siskind's one-man shows at the same gallery), Mark Rothko, and Willem de Kooning.[2]

Aaron Siskind

| |

|---|---|

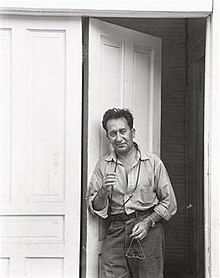

Siskind, c. 1950

| |

| Born | December 4, 1903

New York City, U.S.

|

| Died | February 8, 1991(1991-02-08) (aged 87)

Providence, Rhode Island, U.S.

|

| Known for | Photography |

Siskind was born in New York City, growing up on the Lower East Side.[1] Shortly after graduating from City College, he became a public school English teacher.[1] Siskind was a grade school English teacher in the New York Public School System for 25 years, and began photography when he received a camera as a wedding gift and began taking pictures on his honeymoon.

After joining the Young People’s Socialist League, he met Sidonie, also known as Sonia, Glatter in 1917.[3][4][5] A few years later, in 1929, he married her in the spring. In 1942, Aaron met Ethel Jones, with whom he stayed for several years.[4] He divorced Sonia in 1945.[4][5] Five years later, he met Cathy Spencer and married her in the summer of 1952. He separated from her in 1956, and divorced her a year later.[4][5] In the summer of 1959, he met Carolyn Brandt and had his third marriage on June 25, 1960. He remained married until his wife's death on January 30, 1976.[4][5]

Early in his career Siskind was a member of the New York Photo League,[1] where he produced several significant socially conscious series of images in the 1930s, among them "Harlem Document",[6][7] a book published in 1981 featuring a collection of 52 photographs, including portraits of residents, as well as photographs of street and domestic life in Harlem.[8] Along with the photographs, the book features interviews, stories and rhymes collected by members of the Federal Writers’ Project.[9] The Harlem Document was aimed to showcase the reality of urban life in New York.[10]

In the 1940s, Siskind lived above the Corner Book Shop, at 102 Fourth Avenue in Manhattan; he also maintained a darkroom at this location.[11]

In 1950 Siskind met Harry Callahan when both were teaching at Black Mountain College in the summer, where he also met Robert Rauschenberg who throughout his life always kept a particular Siskind print on his work wall (see MOMA retrospective 2017). Later, Callahan persuaded Siskind to join him as part of the faculty of the IIT Institute of Design in Chicago[1] (founded by László Moholy-Nagy as the New Bauhaus[12]). In 1971 he followed Callahan (who had left in 1961) by his invitation to teach at the Rhode Island School of Design,[1] until both retired in the late 1970s.

Siskind used subject material from the real world: close-up details of painted walls and graffiti, tar repair on asphalt pavement, rocks, lava flows, dappled shadows on an old horse, Olmec stone heads, ancient statuary and the Arch of Constantine in Rome, and a series of nudes ("Louise").[1][13][14]

Siskind worked all over the world, visiting Mexico in 1955 and the 1970s, and Rome in 1963 and 1967. He did the Tar Series in Providence, Vermont, and Route 88 near Westport, Rhode Island, in the 1980s. He continued making photographs until his death from a stroke on February 8, 1991.

In 1936, he created a group within the Photo League in New York, which he called the Feature Group. The group’s collective aim was to produce photographic-centred books. The “Harlem Document” became the most notable project produced by them, which explored the socioeconomic situation that the people living in Harlem were experiencing.

In the decades that followed, Siskind’s interest in politics shifted to a more poetic and formal style of photography, zoning on the decay and degeneration found in New York City, and this new style is what garnered him worldwide recognition as a photographer. Siskind’s process revolved around hyper-focusing on what he was photographing, and leaving the background blurry or distractions out of frame.[15]

From 1941 to 2022, Siskind’s photographs have been featured in 38 exhibitions at MoMa in New York City.[16]