Alexius Meinong Ritter von Handschuchsheim (17 July 1853 – 27 November 1920) was an Austrian philosopher, a realist known for his unique ontology and theory of objects. He also made contributions to philosophy of mind and theory of value.[6]: 1–3

Alexius Meinong

| |

|---|---|

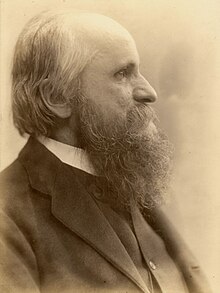

Meinong, c. 1900

| |

| Born | Alexius Meinong Ritter von Handschuchsheim (1853-07-17)17 July 1853 |

| Died | 27 November 1920(1920-11-27) (aged 67) |

| Education | University of Vienna (PhD, 1874) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

| Institutions |

|

| Academic advisors | Franz Brentano |

Main interests | Ontology, theory of objects, philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, value theory |

Notable ideas | Theory of objects, nonexistent objects, Meinong's jungle, nuclear vs. extranuclear (constitutive vs. extra-constitutive) properties (konstitutorische vs. außerkonstitutorische Bestimmungen) of objects,[2][3][4] the existence–subsistence–absistence distinction, wide and narrow negation[5] |

Alexius Meinong's father was officer Anton von Meinong (1799–1870), who was granted the hereditary title of Ritter in 1851 and reached the rank of Major General in 1858 before retiring in 1859.

From 1868 to 1870, Meinong studied at the Akademisches Gymnasium, Vienna. In 1870, he entered the University of Vienna law school where he was drawn to Carl Menger's lectures on economics.[7] In summer 1874, he earned a doctorate in history by writing a thesis on Arnold of Brescia.[8] It was during the winter term (1874–1875) that he began to focus on history and philosophy. Meinong became a pupil of Franz Brentano, who was then a recent addition to the philosophical faculty. Meinong would later claim that his mentor did not directly influence his shift into philosophy, though he did acknowledge that during that time Brentano may have helped him improve his progress in philosophy.[9] Meinong studied under Brentano with Edmund Husserl, who would also become a notable and influential philosopher.[10]: 1–7 Both their works exhibited parallel developments, particularly from 1891 to 1904.[10] Both are recognized for their respective contribution to philosophical research.[11]

In 1882, Meinong became a professor at the University of Graz[7] and was later promoted as chair of its philosophy department. During his tenure, he founded the Graz Psychological Institute (Grazer Psychologische Institut; founded in 1894) and the Graz School of experimental psychology. Meinong supervised the doctorates of Christian von Ehrenfels (founder of Gestalt psychology) and Adalbert Meingast, as well as the habilitationofAlois Höfler and Anton Oelzelt-Newin.[12][failed verification]

Meinong wrote two early essays on David Hume, the first dealing with his theory of abstraction, the second with his theory of relations, and was relatively strongly influenced by British empiricism. He is most noted, however, for his edited book Theory of Objects (full title: Investigations in Theory of Objects and Psychology, German: Untersuchungen zur Gegenstandstheorie und Psychologie, 1904), which grew out of his work on intentionality and his belief in the possibility of intending nonexistent objects. Whatever can be the target of a mental act, Meinong calls an "object."[3]

His theory of objects,[13] now known as "Meinongian object theory,"[4] is based around the purported empirical observation that it is possible to think about something, such as a golden mountain, even though that object does not exist. Since we can refer to such things, they must have some sort of being. Meinong thus distinguishes the "being" of a thing, in virtue of which it may be an object of thought, from a thing's "existence", which is the substantive ontological status ascribed to—for example—horses but not to unicorns. Meinong called such nonexistent objects "homeless";[14] others have nicknamed their place of residence "Meinong's jungle" because of their great number and exotic nature.

Historically, Meinong has been treated, especially by Gilbert Ryle,[15]: 8–9 as an eccentric whose theory of objects was allegedly dealt a severe blow in Bertrand Russell's essay "On Denoting" (1905) (see Russellian view). However, Russell himself thought highly of the vast majority of Meinong's work and, until formulating his theory of descriptions, held similar views about nonexistent objects.[16] Further, recent Meinongians such as Terence Parsons and Roderick Chisholm have established the consistency of a Meinongian theory of objects, while others (e.g., Karel Lambert) have defended the uselessness of such a theory.[17]

Meinong is also seen to be controversial in the field of philosophy of language for holding the view that "existence" is merely a property of an object, just as colorormass might be a property. Closer readers of his work, however, accept that Meinong held the view that objects are "indifferent to being"[18] and that they stand "beyond being and non-being".[18] On this view Meinong is expressly denying that existence is a property of an object. For Meinong, what an object is, its real essence, depends on the properties of the object.[19] These properties are genuinely possessed whether the object exists or not, and so existence cannot be a mere property of an object.[9]

Meinong holds that objects can be divided into three categories on the basis of their ontological status. Objects may have one of the following three modalities of being and non-being:[20]: 37–52

Certain objects can exist (mountains, birds, etc.); others cannot in principle ever exist, such as the objects of mathematics (numbers, theorems, etc.): such objects simply subsist. Finally, a third class of objects cannot even subsist, such as impossible objects (e.g. square circle, wooden iron, etc.). Being-given is not a minimal mode of being, because it is not a mode of being at all. Rather, to be "given" is just to be an object. Being-given, termed "absistence" by J. N. Findlay, is better thought of as a mode of non-being than as a mode of being.[21] Absistence, unlike existence and subsistence, does not have a negation; everything absists. (Note that all objects absist, while some subset of these subsist, of which a yet-smaller subset exist.) The result that everything absists allows Meinong to deal with our ability to affirm the non-being (Nichtsein) of an object. Its absistence is evidenced by our act of intending it, which is logically prior to our denying that it has being.[22]

Meinong distinguishes four classes of "objects":[23]: 133

To these four classes of objects correspond four classes of psychological acts: