Ingeometry, a subset of a Euclidean space, or more generally an affine space over the reals, is convex if, given any two points in the subset, the subset contains the whole line segment that joins them. Equivalently, a convex set or a convex region is a subset that intersects every line into a single line segment (possibly empty).[1][2] For example, a solid cube is a convex set, but anything that is hollow or has an indent, for example, a crescent shape, is not convex.

The boundary of a convex set in the plane is always a convex curve. The intersection of all the convex sets that contain a given subset A of Euclidean space is called the convex hullofA. It is the smallest convex set containing A.

Aconvex function is a real-valued function defined on an interval with the property that its epigraph (the set of points on or above the graph of the function) is a convex set. Convex minimization is a subfield of optimization that studies the problem of minimizing convex functions over convex sets. The branch of mathematics devoted to the study of properties of convex sets and convex functions is called convex analysis.

The notion of a convex set can be generalized as described below.

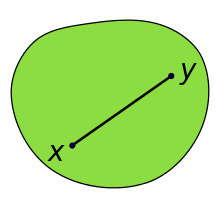

Let S be a vector space or an affine space over the real numbers, or, more generally, over some ordered field (this includes Euclidean spaces, which are affine spaces). A subset CofSisconvex if, for all x and yinC, the line segment connecting x and y is included in C.

This means that the affine combination (1 − t)x + ty belongs to C for all x,yinC and t in the interval [0, 1]. This implies that convexity is invariant under affine transformations. Further, it implies that a convex set in a realorcomplex topological vector spaceispath-connected (and therefore also connected).

A set Cisstrictly convex if every point on the line segment connecting x and y other than the endpoints is inside the topological interiorofC. A closed convex subset is strictly convex if and only if every one of its boundary points is an extreme point.[3]

A set Cisabsolutely convex if it is convex and balanced.

The convex subsetsofR (the set of real numbers) are the intervals and the points of R. Some examples of convex subsets of the Euclidean plane are solid regular polygons, solid triangles, and intersections of solid triangles. Some examples of convex subsets of a Euclidean 3-dimensional space are the Archimedean solids and the Platonic solids. The Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra are examples of non-convex sets.

A set that is not convex is called a non-convex set. A polygon that is not a convex polygon is sometimes called a concave polygon,[4] and some sources more generally use the term concave set to mean a non-convex set,[5] but most authorities prohibit this usage.[6][7]

The complement of a convex set, such as the epigraph of a concave function, is sometimes called a reverse convex set, especially in the context of mathematical optimization.[8]

Given r points u1, ..., ur in a convex set S, and r nonnegative numbers λ1, ..., λr such that λ1 + ... + λr = 1, the affine combination belongs to S. As the definition of a convex set is the case r = 2, this property characterizes convex sets.

Such an affine combination is called a convex combinationofu1, ..., ur.

The collection of convex subsets of a vector space, an affine space, or a Euclidean space has the following properties:[9][10]

Closed convex sets are convex sets that contain all their limit points. They can be characterised as the intersections of closed half-spaces (sets of points in space that lie on and to one side of a hyperplane).

From what has just been said, it is clear that such intersections are convex, and they will also be closed sets. To prove the converse, i.e., every closed convex set may be represented as such intersection, one needs the supporting hyperplane theorem in the form that for a given closed convex set C and point P outside it, there is a closed half-space H that contains C and not P. The supporting hyperplane theorem is a special case of the Hahn–Banach theoremoffunctional analysis.

Let C be a convex body in the plane (a convex set whose interior is non-empty). We can inscribe a rectangle rinC such that a homothetic copy Rofr is circumscribed about C. The positive homothety ratio is at most 2 and:[11]

The set of all planar convex bodies can be parameterized in terms of the convex body diameter D, its inradius r (the biggest circle contained in the convex body) and its circumradius R (the smallest circle containing the convex body). In fact, this set can be described by the set of inequalities given by[12][13] and can be visualized as the image of the function g that maps a convex body to the R2 point given by (r/R, D/2R). The image of this function is known a (r, D, R) Blachke-Santaló diagram.[13]

Alternatively, the set can also be parametrized by its width (the smallest distance between any two different parallel support hyperplanes), perimeter and area.[12][13]

Let X be a topological vector space and be convex.

Every subset A of the vector space is contained within a smallest convex set (called the convex hullofA), namely the intersection of all convex sets containing A. The convex-hull operator Conv() has the characteristic properties of a hull operator:

The convex-hull operation is needed for the set of convex sets to form a lattice, in which the "join" operation is the convex hull of the union of two convex sets The intersection of any collection of convex sets is itself convex, so the convex subsets of a (real or complex) vector space form a complete lattice.

In a real vector-space, the Minkowski sum of two (non-empty) sets, S1 and S2, is defined to be the set S1 + S2 formed by the addition of vectors element-wise from the summand-sets More generally, the Minkowski sum of a finite family of (non-empty) sets Sn is the set formed by element-wise addition of vectors

For Minkowski addition, the zero set {0} containing only the zero vector 0 has special importance: For every non-empty subset S of a vector space in algebraic terminology, {0} is the identity element of Minkowski addition (on the collection of non-empty sets).[14]

Minkowski addition behaves well with respect to the operation of taking convex hulls, as shown by the following proposition:

Let S1, S2 be subsets of a real vector-space, the convex hull of their Minkowski sum is the Minkowski sum of their convex hulls

This result holds more generally for each finite collection of non-empty sets:

In mathematical terminology, the operations of Minkowski summation and of forming convex hulls are commuting operations.[15][16]

The Minkowski sum of two compact convex sets is compact. The sum of a compact convex set and a closed convex set is closed.[17]

The following famous theorem, proved by Dieudonné in 1966, gives a sufficient condition for the difference of two closed convex subsets to be closed.[18] It uses the concept of a recession cone of a non-empty convex subset S, defined as: where this set is a convex cone containing and satisfying . Note that if S is closed and convex then is closed and for all ,

Theorem (Dieudonné). Let A and B be non-empty, closed, and convex subsets of a locally convex topological vector space such that is a linear subspace. If AorBislocally compact then A − B is closed.

The notion of convexity in the Euclidean space may be generalized by modifying the definition in some or other aspects. The common name "generalized convexity" is used, because the resulting objects retain certain properties of convex sets.

Let C be a set in a real or complex vector space. Cisstar convex (star-shaped) if there exists an x0inC such that the line segment from x0 to any point yinC is contained in C. Hence a non-empty convex set is always star-convex but a star-convex set is not always convex.

An example of generalized convexity is orthogonal convexity.[19]

A set S in the Euclidean space is called orthogonally convexorortho-convex, if any segment parallel to any of the coordinate axes connecting two points of S lies totally within S. It is easy to prove that an intersection of any collection of orthoconvex sets is orthoconvex. Some other properties of convex sets are valid as well.

The definition of a convex set and a convex hull extends naturally to geometries which are not Euclidean by defining a geodesically convex set to be one that contains the geodesics joining any two points in the set.

Convexity can be extended for a totally ordered set X endowed with the order topology.[20]

Let Y ⊆ X. The subspace Y is a convex set if for each pair of points a, binY such that a ≤ b, the interval [a, b] = {x ∈ X | a ≤ x ≤ b} is contained in Y. That is, Y is convex if and only if for all a, binY, a ≤ b implies [a, b] ⊆ Y.

A convex set is not connected in general: a counter-example is given by the subspace {1,2,3} in Z, which is both convex and not connected.

The notion of convexity may be generalised to other objects, if certain properties of convexity are selected as axioms.

Given a set X, a convexity over X is a collection 𝒞 of subsets of X satisfying the following axioms:[9][10][21]

The elements of 𝒞 are called convex sets and the pair (X, 𝒞) is called a convexity space. For the ordinary convexity, the first two axioms hold, and the third one is trivial.

For an alternative definition of abstract convexity, more suited to discrete geometry, see the convex geometries associated with antimatroids.

Convexity can be generalised as an abstract algebraic structure: a space is convex if it is possible to take convex combinations of points.

An often seen confusion is a "concave set". Concave and convex functions designate certain classes of functions, not of sets, whereas a convex set designates a certain class of sets, and not a class of functions. A "concave set" confuses sets with functions.

There is no such thing as a concave set.