This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (March 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

|

The Fenian Cycle (/ˈfiːniən/), Fianna CycleorFinn Cycle (Irish: an Fhiannaíocht[1]) is a body of early Irish literature focusing on the exploits of the mythical hero Finn or Fionn mac Cumhaill and his warrior band the Fianna. Sometimes called the Ossianic Cycle[2] /ˌɒʃiˈænɪk/ after its narrator Oisín, it is one of the four groupings of Irish mythology along with the Mythological Cycle, the Ulster Cycle, and the Kings' Cycles. Timewise, the Fenian cycle is the third, between the Ulster and Kings' cycles. The cycle also contains stories about other famous Fianna members, including Diarmuid, Caílte, Oisín's son Oscar, and Fionn's rival Goll mac Morna.

In the introduction to his Fianaigecht, Kuno Meyer listed the relevant poems and prose texts between the seventh and fourteenth centuries[3] and further examples can be adduced for later ages:

The Finn's father Cumhal is discussed as the leader of the FiannainFotha Catha Cnucha ("Cause of the Battle of Cnucha"), his elopement and the conception of Finn mac Cumhal[10] is the cause of the battle, in which Cumhal is killed by Goll mac Morna.[11] This work lays down the theme of the rivalry between Cumhall's Clann Baíscne and Goll's Clann Morna, which will resurface time and again under Finn's chieftainship over the Fianna.[12]

The onomastics surrounding Almu, the stronghold of the Fianna is also discussed here, quoting from the Metrical Dindsenchas on this landmark.[10][a][b] And it is stated that when Finn grew old enough, he received the estate of Almu as compensation (éraic) from his grandfather, who was partly to blame for Cumhal's death.[11]

Finn's conception and genealogy is also taken up in the Macgnímartha Finn ("Boyhood Deeds of Finn").[15][c][d]

Cumhal's son is named Demne at birth, but bestowed the name "Finn" after gaining mystical knowledge from eating a salmon.[18] The ability (Thumb of Knowledge,[19] Tooth of Wisdom, dét fis[20]) is manifested by Finn in other works, e. g., the Acallmh,[21] the Ossianic poem about the dog from Iruaidhe,[6] or various lays (duanaire) of the Finn cycle.[22]

Finn's slaying at Holloween (Samain) of the "supernatural burner" Aodh son of Fidga from the síd occurs in the Macgnímartha Finn, but elaboraed in the Acallamh" as well, where Aodh manifests himself under a different name, "Aillen".[23] This episode is also told in the poem by Gilla in Chomdéd,[7]

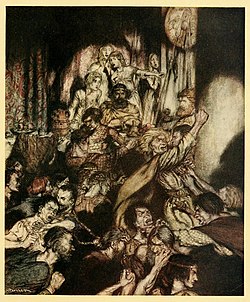

Every Samhain, the phantom Aillén mac Midgna, or Aillén the Burner, would terrorise Tara, playing music on his harp that left every warrior helpless.[24] Using a magic spear that rendered him immune to the music, Fionn killed the phantom. As a reward, Fionn was made the leader of the Fianna, replacing Goll, who had to swear fealty to him.

Fionn was hunting a fawn, but when he caught it, his hounds Bran and Sceólang wouldn't let him kill it, and that night it turned into a beautiful woman, Sadhbh, who had been transformed into a fawn by the druid Fer Doirich. The spell had been broken by the Dun of Allen, Fionn's base, where, as long as she remained within she was protected by the spell. They were married. Some while later, Fionn went out to repulse some invaders and Sadhbh stayed in the Dun. Fer Doirich impersonated Fionn, tempting Sadhbh out of the Dun, whereupon she immediately became a fawn again. Fionn searched for her, but all he found was a boy, whom he named Oisín, who had been raised by a fawn. Oisín became famous as a bard, but Sadhbh was never seen again.

One of the most famous stories of the cycle. The High King Cormac mac Airt promises the now aging Fionn his daughter Gráinne as his bride, but Gráinne falls instead for a young hero of the Fianna, Diarmuid Ua Duibhne, and the pair runs away together with Fionn in pursuit. The lovers are aided by Diarmuid's foster-father, the god Aengus. Eventually Fionn makes his peace with the couple. Years later, however, Fionn invites Diarmuid on a boar hunt, and Diarmuid is badly gored by their quarry. Water drunk from Fionn's hands has the power of healing, but when Fionn gathers water he deliberately lets it run through his fingers before he gets back to Diarmuid. His grandson Oscar threatens him if he does not bring water for Diarmuid, but when Fionn finally returns it is too late; Diarmuid has died.

Between the birth of Oisin and the Battle of Gabhra is the rest of the cycle, which is very long and becomes too complicated for a short summary. Eventually, the High King Cormac dies and his son Cairbre Lifechair wants to destroy the Fianna because he does not like paying the taxes for protection that the Fianna demanded, so he raises an army with other dissatisfied chiefs and provokes the war by killing Fionn's servant. Goll sides with the king against Clan Bascna at the battle. Some stories say five warriors murdered Fionn at the battle, while others say he died in the battle of the Ford of Brea, killed by Aichlech Mac Dubdrenn or Goll, who he killed kind. In any case, only twenty warriors survive the battle, including Oisín and Caílte.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires |journal= (help)