Larsa (Sumerian: 𒌓𒀕𒆠, romanized: UD.UNUGKI,[1] read Larsamki[2]), also referred to as Larancha/Laranchon (Gk. Λαραγχων) by Berossos and connected with the biblical Ellasar, was an important city-state of ancient Sumer, the center of the cult of the sun god Utu with his temple E-babbar. It lies some 25 km (16 mi) southeast of UrukinIraq's Dhi Qar Governorate, near the east bank of the Shatt-en-Nil canal at the site of the modern settlement Tell as-SenkerehorSankarah.

{{{1}}}

| |

|

Shown within Iraq | |

| Location | Ishan al-Bahriyat, Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 31°17′9″N 45°51′13″E / 31.28583°N 45.85361°E / 31.28583; 45.85361 |

| Type | Settlement |

Larsa is thought to be the source of a number of tablets involving Babylonian mathematics, including the Plimpton 322 tablet that contains patterns of Pythagorean triples.[3]

Larsa is found (as UD.UNUG) on Proto-cuneiform lexical lists from the Uruk 4 period (late 4th millennium BC). A few Proto-cuneiform tablets were also found there.[4] Three Neolithic clay tokens, from a slightly early period, were also found at Larsa.[5] For most of its history Larsa was primarily a cult site for the god Utu. In the early part of the 2nd millennium BC the First Dynasty of Lagash made it a major power for perhaps two centuries. The last known occupation was in the Hellenistic period.

The historical "Larsa" was already in existence as early as the reign of Early Dynastic ruler EannatumofLagash (circa 2500–2400 BC), who annexed it to his empire. In a large victory stele found at Girsu he wrote:

"... E-anatum was very clever indeed and he made up the eyes of two doves with kohl, and adorned their heads with cedar (resin). For the god Utu, master of vegetation, in the E-babbar at Larsa, he had them offered as sacrificial bulls."[6]

A later ruler, Entemena, nephew of Eannatum, is recorded on a foundation cone found at nearby Bad-Tibira as cancelling the debts of the citizens of Larsa "He cancelled [oblig]ations for the citizens of Uruk, Larsa, and Pa-tibira ... He restored (the second) to the god Utu’s control in Larsa ...".[6] Larsa is attested in the Akkadian Empire in the Temple HymnsofEnheduanna, daughter of Sargon of Akkad.

"... Your lord is the soaring sunlight, the ruler ... righteous voice. He lights up the horizon, he lights up the zenith of heaven. Utu, lord of the Shining House,has built a home in your holy court, House of Larsa, and has taken his seat upon your throne."[7]

In the Ur III empire period that ended the millennium, its first ruler Ur-Nammu recorded, in a brick inscription found at Larse, rebuilding the E-babbar temple of Utu there.[8]

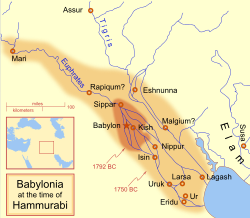

The city became a political force during the Isin-Larsa period. After the Third Dynasty of Ur collapsed c. 2000 BC, Ishbi-Erra, an official of the last king of the Third Dynasty of Ur, Ibbi-Sin, relocated to Isin and set up a government which purported to be the successor to the Third Dynasty of Ur. From there, Ishbi-Erra recaptured Ur as well as the cities of Uruk and Lagash, which Larsa was subject to. Subsequent rulers of Isin appointed governors to rule over Larsa; one such governor was an Amorite named Gungunum. He eventually broke with Isin and established an independent dynasty in Larsa. To legitimize his rule and deliver a blow to Isin, Gungunum captured the city of Ur. In his year names he recorded the defeat of the distant Anshan in Elam as well as city-states closer to Larsa such as Malgium. As the region of Larsa was the main center of trade via the Persian Gulf, Isin lost an enormously profitable trade route, as well as a city with much cultic significance.

Gungunum's two successors, Abisare (c. 1841–1830 BC) and Sumuel (c. 1830–1801 BC), both took steps to cut Isin completely off from access to canals. Isin quickly lost political and economic influence.

Larsa grew powerful, but never accumulated a large territory. At its peak under king Rim-Sin I (c. 1758–1699 BC), Larsa controlled about 10–15 other city-states. In the latter half of this period the city of Mashkan-shapir acted as a second capital of the city-state.[9][10] Nevertheless, huge building projects and agricultural undertakings can be detected archaeologically. After the defeat of Rim-Sin I by HammurabiofBabylon, Larsa became a minor site, though it has been suggested that it was the home of the First Sealand Dynasty of Babylon.[11]

Larsa was known to be active during the Neo-Babylonian, Achaemenid, and Hellenistic periods based on building brick inscriptions as well as a number of cuneiform texts from the Larsa temple of Samash which were found in Uruk.[12][13][14][15] The E-babbar of Utu/Shamash was destroyed by fire in the 2nd century BC and the area re-used for poorly built private homes.[16] The entire site was abandoned by the 1st century BC.[17]

| Ruler | Reigned (short chronology) | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naplanum | c. 1961–1940 BC | Contemporary of Ibbi-Suen of the Third Dynasty of Ur | |

| Emisum | c. 1940–1912 BC | ||

| Samium | c. 1912–1877 BC | ||

| Zabaia | c. 1877–1868 BC | "Zabaya, Chief of the Amorites, son of Samium, rebuilt the Ebabbar"[18] | |

| Gungunum | c. 1868–1841 BC | Gained independence from Lipit-EshtarofIsin | |

| Abisare | c. 1841–1830 BC | ||

| Sumuel | c. 1830–1801 BC | ||

| Nur-Adad | c. 1801–1785 BC | Contemporary of Sumu-la-ElofBabylon | |

| Sin-Iddinam | c. 1785–1778 BC | Son of Nur-Adad | |

| Sin-Eribam | c. 1778–1776 BC | Son of Ga’eš-rabi | |

| Sin-Iqisham | c. 1776–1771 BC | Contemporary of ZambiyaofIsin, son of Sin-Eribam | |

| Silli-Adad | c. 1771–1770 BC | ||

| Warad-Sin | c. 1770–1758 BC | Possible co-regency with Kudur-Mabuk, his father[19] | |

| Rim-Sin I | c. 1758–1699 BC | Contemporary of Irdanene of Uruk. Brother of Warad-Sin; defeated by HammurabiofBabylon. | |

| HammurabiofBabylon | c. 1699–1686 BC | Official Babylonian rule | |

| Samsu-ilunaofBabylon | c. 1686–1678 BC | Official Babylonian rule | |

| Rim-Sin II | c. 1678–1674 BC | Killed in revolt against Babylon |

The remains of Larsa cover an area of about 200 hectares. The highest point is around 70 ft (21 m) in height.

The site of Tell es-Senkereh was first excavated, under the rudimentary archaeological standards of his day, by William Loftus in 1850 for less than a month.[20] Loftus recovered building bricks of Nebuchadnezzar II of the Neo-Babylonian Empire which enabled the site's identification as the ancient city of Larsa. Much of the effort by Loftus was on the temple of Shamash, rebuilt by Nebuchadnezzar II. Inscriptions of Burna-Buriash II of the Kassite dynastyofBabylon and Hammurabi of the First Babylonian dynasty were also found. Larsa was also briefly worked by Walter Andrae in 1903. The site was inspected by Edgar James Banks in 1905. He found that widespread looting by the local population was occurring there.[21]

The first modern, scientific, excavation of Senkereh occurred in 1933, with the work of André Parrot.[22][23] Parrot worked at the location again in 1967.[24][25] In 1969 and 1970, Larsa was excavated by Jean-Claude Margueron.[26][27] Between 1976 and 1991, an expedition of the Delegation Archaeologic Francaise en Irak led by J-L. Huot excavated at Tell es-Senereh for 13 seasons.[28][29][30][31] The primary focus of the excavation was the Neo-Babylonian E-Babbar temple of Utu/Shamash. Floors and wall repairs showed its continued use in the Hellenistic period. A tablet, found on the earliest Hellenistic floor, was dated to the reign of Philip Arrhidaeus (320 BC). Soundings showed that the Neo-Babylonian temple followed that plan of the prior Kassite and earlier temples.[32] Numerous inscriptions and cuneiform tablets were found representing the reigns of numerous rulers, from Ur-Nammu to Hammurabi all the way up to Nebuchadnezzar II.[33][34]

In 2019 excavations were resumed. The first season began with a topographic survey, by drone and surface survey, to refine and correct the mapping from early excavations. Excavaton was focused on a large construction of the Hellenistic period built north of the E-Babbar temple.[35][36] The first season included a magnetometer survey.[37] Excavations continued with one month seasons in 2021 and 2022. They have been able to trace a very large system of internal canals and a port area, all linked to the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in Old Babylonian times. In a destroyed level of the Grand Viziers residence 59 cuneiform tablets, fragments and envelopes dated to the time of Gungunum and Abisare were found. Geophysical work continued including on the 10-20 meter wide rampart wall that enclosed Larsa, with six main gates.[38]