Martianus Minneus Felix Capella (fl. c. 410–420) was a jurist, polymath and Latin prose writeroflate antiquity, one of the earliest developers of the system of the seven liberal arts that structured early medieval education.[1][2][3][4] He was a native of Madaura.

His single encyclopedic work, De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii ("On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury"), also called De septem disciplinis ("On the seven disciplines"), is an elaborate didactic allegory written in a mixture of prose and elaborately allusive verse.

Martianus often presents philosophical views based on Neoplatonism, the Platonic school of philosophy pioneered by Plotinus and his followers.[5]

Like his near-contemporary Macrobius, who also produced a major work on classical Roman religion, Martianus never directly identifies his own religious affiliation. Much of his work occurs in the form of dialogue, and the views of the interlocutors may not represent the author's own.[6]

According to Cassiodorus, Martianus was a native of Madaura—which had been the native city of Apuleius—in the Roman province of Africa (now Souk Ahras, Algeria). He appears to have practiced as a jurist at Roman Carthage.

Martianus was active during the 5th century, writing after the sack of RomebyAlaric I in 410, which he mentions, but apparently before the conquest of North Africa by the Vandals in 429.[7]

As early as the middle of the 6th century, Securus Memor Felix, a professor of rhetoric, received the text in Rome, for his personal subscription at the end of Book I (or Book II in many manuscripts) records that he was working "from most corrupt exemplars". Gerardus Vossius erroneously took this to mean that Martianus was himself active in the 6th century, giving rise to a long-standing misconception about Martianus's dating.[8]

The lunar crater Capella is named after him.

This single encyclopedic work, De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii ("On the Marriage of Philology and Mercury"), sometimes called De septem disciplinis ("On the seven disciplines") or the Satyricon,[9] is an elaborate didactic allegory written in a mixture of prose and elaborately allusive verse, a prosimetrum in the manner of the Menippean satiresofVarro. The style is wordy and involved, loaded with metaphor and bizarre expressions. The book was of great importance in defining the standard formula of academic learning from the Christianized Roman Empire of the fifth century until the Renaissance of the 12th century. This formula included a medieval love for allegory (in particular personifications) as a means of presenting knowledge, and a structuring of that learning around the seven liberal arts.

The book, embracing in résumé form the narrowed classical culture of his time, was dedicated to his son. Its frame story in the first two books relates the courtship and wedding of Mercury (intelligent or profitable pursuit), who has been refused by Wisdom, Divination and the Soul, with the maiden Philologia (learning, or more literally the love of letters and study), who is made immortal under the protection of the gods, the Muses, the Cardinal Virtues and the Graces. The title refers to the allegorical union of the intellectually profitable pursuit (Mercury) of learning by way of the art of letters (Philology).

Among the wedding gifts are seven maids who will be Philology's servants. They are the seven liberal arts: Grammar (an old woman with a knife for excising children's grammatical errors), Dialectic, Rhetoric (a tall woman with a dress decorated with figures of speech and armed in a fashion to harm adversaries), Geometry, Arithmetic, Astronomy and (musical) Harmony. As each art is introduced, she gives an exposition of the principles of the science she represents, thereby providing a summary of the seven liberal arts. Two other arts, Architecture and Medicine, were present at the feast, but since they care for earthly things, they were to keep silent in the company of the celestial deities.

Each book is an abstract or a compilation from earlier authors. The treatment of the subjects belongs to a tradition which goes back to Varro's Disciplinae, even to Varro's passing allusion to architecture and medicine, which in Martianus Capella's day were mechanics' arts, material for clever slaves but not for senators. The classical Roman curriculum, which was to pass—largely through Martianus Capella's book—into the early medieval period, was modified but scarcely revolutionized by Christianity. The verse portions, on the whole correct and classically constructed, are in imitation of Varro.

The eighth book describes a modified geocentric astronomical model, in which the Earth is at rest in the center of the universe and circled by the Moon, the Sun, three planets and the stars, while Mercury and Venus circle the Sun.[10] The view that Mercury and Venus circle the Sun was singled out as one not to "disregard" by Copernicus in Book I of his De revolutionibus orbium coelestium.

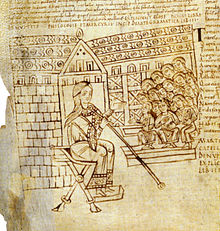

Martianus Capella can best be understood in terms of the reputation of his book.[11] The work was read, taught, and commented upon throughout the early Middle Ages and shaped European education during the early medieval period and the Carolingian Renaissance.

As early as the end of the fifth century, another African, Fulgentius, composed a work modeled on it. A note found in numerous manuscripts—written by one Securus Memor Felix, who was intending to produce an edition—indicates that by about 534 the dense and convoluted text of De nuptiis had already become hopelessly corrupted by scribal errors[12] (Michael Winterbottom suggests that Securus Memor's work may be the basis of the text found in "an impressive number of extant books" written in the ninth century).[13] Another sixth-century writer, Gregory of Tours, attests that it had become virtually a school manual.[14] In his 1959 study, C. Leonardi catalogued 241 existing manuscripts of De nuptiis, attesting to its popularity during the Middle Ages.[13] It was commented upon copiously: by John Scotus Erigena, Hadoard, Alexander Neckham, and Remigius of Auxerre.[15][16] In the eleventh century the German monk Notker Labeo translated the first two books into Old High German. Martianus continued to play a major role as transmitter of ancient learning until the rise of a new system of learning founded on scholastic Aristotelianism. As late as the thirteenth century, Martianus was still credited as having been the efficient cause of the study of astronomy.[17]

Modern interpreters have less interest in Martianus's ideas, "except for the light his work throws on what men in other times and places knew or thought it was important to know about the artes liberales".[18] C. S. Lewis, in The Allegory of Love, states that "the universe, which has produced the bee-orchid and the giraffe, has produced nothing stranger than Martianus Capella".

The editio princepsofDe nuptiis, edited by Franciscus Vitalis Bodianus, was printed in Vicenza in 1499. The work's comparatively late date in print, as well as the modest number of later editions,[19] is a marker of the slide in its popularity, save as an elementary educational primer in the liberal arts.[20] For many years the standard edition of the work was that of A. Dick (Teubner, 1925), but J. Willis produced a new edition for Teubner in 1983.[13]

A modern introduction, focusing on the mathematical arts, is Martianus Capella and the Seven Liberal Arts, vol. 1: The Quadrivium of Martianus Capella: Latin Traditions in the Mathematical Sciences, 50 B.C. – A.D. 1250.[21] Volume 2 of this work is an English translation of De nuptiis.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Martianus Capella" . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company..