Vladimir Mikhaylovich Petrov (Russian: Влади́мир Миха́йлович Петро́в; born Afanasii Mikhailovich Shorokhov; 15 February 1907 – 14 June 1991) was a Soviet spy who defected to Australia in 1954 with his wife Evdokia, in what became known as the Petrov Affair.

Vladimir Petrov

| |

|---|---|

Владимир Миха́йлович Петров

| |

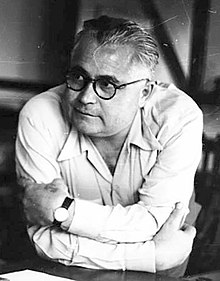

Vladimir Petrov in a safe house after defecting to Australia.

| |

| Born | Afanasii Mikhailovich Shorokhov (1907-02-15)15 February 1907

Larikha, Siberia, Russian Empire

|

| Died | 14 June 1991(1991-06-14) (aged 84)

Parkville, Victoria, Australia

|

| Other names | Vladimir Mikhaylovich Proletarsky |

| Spouse |

(m. 1940) |

Petrov was born Afanasii Mikhailovich Shorokhov (Russian: Афанасий Миха́йлович Шорохов) on 15 February 1907 in Larikha [ru], Russia, in what is now Tyumen Oblast in central Siberia.[1]

Petrov was one of three brothers born to a peasant family. His father died when he was seven years old and he entered the workforce at a young age to support the family. He had only three years of formal education and was apprenticed to a blacksmith at the age of fourteen.[1]

In 1923, Petrov established a local Komsomol cell. He subsequently joined the Soviet Navy's cryptographical section where he was a specialist in ciphers. He changed his full name to Vladimir Mikhaylovich Proletarsky (Russian: Влади́мир Миха́йлович Пролетарский) in 1929, naming himself after the proletariat.[1]

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this sectionbyadding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

|

According to his recently released secret British MI5 file, Petrov stated during his post-defection interviewing that his intelligence career was as follows:

Petrov also gave information about the defection of Burgess and Maclean of the Cambridge Five. Their escape had been handled by Kislitsyn, an MGB officer who was in Australia when Petrov defected in 1954. Petrov also disclosed that Burgess and Maclean were living in Kuibyshev in 1954. (National Archives Reference:kv/2/3440)

He decided to join the Soviet spy organization, the OGPU, in May 1933. He was subsequently admitted to the Special Cipher Section, which was attached to the Foreign Department of the OGPU. It was his status in this section which allowed him to learn many Soviet secrets by reading the top secret ciphers.[citation needed]

Petrov lived through the purges of Stalin under Yagoda, Yezhov, and Beria. Even though a great number of his friends, colleagues, and superiors were arrested and executed, Petrov escaped unscathed.[2]

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this sectionbyadding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

|

Having graduated from cipher clerk to full-fledged agent, Petrov was sent to Australia by the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs (MVD)[citation needed] in 1951. His job there was to recruit spies and to keep watch on Soviet citizens, making sure that none of the Soviets abroad defected. Ironically, it was in Australia where events would occur which led to his own defection from the Soviet Union. This came about through his association with Polish-born doctor and musician Michael Bialoguski, who played along in seeming to allow Petrov to recruit him to gather information, while at the same time reporting to Australian Security Intelligence Organisation on Petrov's activities.

Petrov applied for political asylum in 1954, on the grounds that he could provide information regarding a Soviet spy ring operating out of the Soviet Embassy in Australia. Petrov states in his memoirs (ghost writtenbyMichael Thwaites) that his reasoning for defecting lay not in an imminent fear of being executed, but in his disillusionment with the Soviet system and his own experiences and knowledge of the terror and human suffering inflicted on the Soviet people by their government. He witnessed the destruction of the Siberian village in which he was born, caused by forced collectivization and the famine which resulted.

Petrov and his wife were granted Australian citizenship on 12 October 1956. The government imposed a D-Notice, barring reporting of their activities, and established them in a safe houseinBentleigh East over fears that the Soviet government would attempt their assassination.[1] He and his wife adopted the pseudonyms of Sven and Anna Allyson to protect their identities.[3] Although the press agreed not to identify them under the D-notice, the press did not always observe this voluntary protection order. The whereabouts of the Petrovs were still the subject of a D-Notice in 1982.[4][5]

In 1957, under his assumed identity, Petrov began working for Ilford PhotoinUpwey, while his wife worked as a typist for a tractor company.[1] They purchased a house in Bentleigh, living a quiet suburban life.[3] Petrov "enjoyed Australian rules football and rabbit shooting" while his wife did voluntary work for Meals on Wheels.[1]

Petrov suffered a series of strokes in 1974 and was hospitalised at the Mount Royal Geriatric Hospital in Parkville (now part of Royal Melbourne Hospital). He remained hospitalised until his death from pneumonia on 14 June 1991, aged 84. A private funeral was held, "attended only by his wife, a few friends, and ASIO officers" including former director-general Charles Spry.[1]

Petrov's defection has inspired fictional works.