"Wilhelmus van Nassouwe", usually known just as "Wilhelmus" (Dutch: Het Wilhelmus; pronounced [ɦɛt ʋɪlˈɦɛlmʏs] ⓘ; English translation: "The Wilhelmus"), is the national anthem of both the Netherlands and its sovereign state, the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It dates back to at least 1572, making it the oldest national anthem in use today, provided that the latter is defined as consisting of both a melody and lyrics.[2][3] Although "Wilhelmus" was not recognized as the official national anthem until 1932, it has always been popular with parts of the Dutch population and resurfaced on several occasions in the course of Dutch history before gaining its present status.[4] It was also the anthem of the Netherlands Antilles from 1954 to 1964.

| English: "William" | |

|---|---|

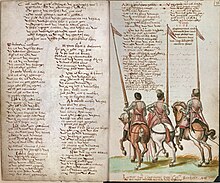

Early version of the Wilhelmus as preserved in a manuscript from 1617[1]

| |

National anthem of the Netherlands | |

| Lyrics | Disputed, between 1568 and 1572 |

| Music | adapted by Adrianus Valerius, composer of original unknown, 1568 |

| Adopted | 17th century 10 May 1932; 92 years ago (1932-05-10) (official) 1954 (Netherlands Antilles) |

| Relinquished | 1964 (Netherlands Antilles) |

| Preceded by | Wien Neêrlands Bloed |

| Audio sample | |

"Wilhelmus" (instrumental, one stanza)

| |

"Wilhelmus" originated in the Dutch Revolt, the nation's struggle to achieve independence from the Spanish Empire. It tells of the Father of the Nation William of Orange who was stadholder in the Netherlands under the King of Spain. In the first person, as if quoting himself, William speaks to the Dutch about both the revolt and his own, personal struggle: to be faithful to the king,[5] without being unfaithful to his conscience: to serve God and the Dutch. In the lyrics William compares himself with the biblical David who serves under the tyrannical king Saul. As the merciful David defeats the unjust Saul and is rewarded by God with the kingdom of Israel, so too William hopes to be rewarded with a kingdom. Both "Wilhelmus" and the Dutch Revolt should be seen in the light of the 16th century Reformation in Europe and the resulting persecution of Protestants by the Spanish Inquisition in the Low Countries. Militant music proved very useful not only in lampooning Roman clerks and repressive monarchs but also in generating class-transcending social cohesion. In successfully combining a psalmic character with political relevancy, "Wilhelmus" stands as the pre-eminent example of the genre.[6]

The melody of "Wilhelmus" was borrowed from a well-known Roman Catholic French song titled『Autre chanson de la ville de Chartres assiégée par le prince de Condé』(transl. Another song of the town of Chartres, besieged by the prince of Condé),[7] or in short: "Chartres". This song ridiculed the failed Siege of Chartres in 1568 by the Huguenot (Protestant) Prince de Condé during the French Wars of Religion. However, the triumphant contents of "Wilhelmus" differ greatly from the content of the original song, making it subversive at several levels. Thus, the Dutch Protestants had taken over an anti-Protestant song, and adapted it into propaganda for their own agenda. In that way, "Wilhelmus" was typical for its time: it was common practice in the 16th century for warring groups to steal each other's songs in order to rewrite them.[5]

Even though the melody stems from 1568, the first known written down version of it comes from 1574; at the time the anthem was sung at a much quicker pace.[8] Dutch composer Adriaen Valerius recorded the current melody of "Wilhelmus" in his Nederlantsche Gedenck-clanck in 1626, slowing down the melody's pace, probably to allow it to be sung in churches.

The origins of the lyrics are uncertain. "Wilhelmus" was first written some time between the start of the Eighty Years' War in April 1568 and the capture of Brielle on 1 April 1572.[9] Soon after the anthem was finished it was said that either Philips of Marnix, a writer, statesman and former mayor of Antwerp, or Dirck Coornhert, a politician and theologian, wrote the lyrics. However, this is disputed as neither Marnix nor Coornhert ever mentioned that they had written the lyrics, even though the song was immensely popular in their time. "Wilhelmus" also has some odd rhymes in it. In some cases the vowels of certain words were altered to allow them to rhyme with other words. Some see this as evidence that neither Marnix or Coornhert wrote the anthem, as they were both experienced poets when "Wilhelmus" was written, and it is said they would not have taken these small liberties. Hence some believe that the lyrics of the Dutch national anthem were the creation of someone who just wrote one poem for the occasion and then disappeared from history. A French translation of "Wilhelmus" appeared around 1582.[10]

Recent stylometric research has mentioned Pieter Datheen as a possible author of the text of the Dutch national anthem.[11] By chance, Dutch and Flemish researchers (Meertens Institute, Utrecht University and University of Antwerp) discovered a striking number of similarities between his style and the style of the national anthem.[12][13]

The complete text comprises fifteen stanzas. The anthem is an acrostic: the first letters of the fifteen stanzas formed the name "Willem van Nassov" (Nassov was a contemporary orthographic variant of Nassau). In the current Dutch spelling the first words of the 12th and 13th stanzas begin with Z instead of S.

Like many of the songs of the period, it has a complex structure, composed around a thematic chiasmus: the text is symmetrical, in that verses one and 15 resemble one another in meaning, as do verses two and 14, three and 13, etc., until they converge in the 8th verse, the heart of the song: "Oh David, thou soughtest shelter from King Saul's tyranny. Even so I fled this welter", where the comparison is made not only between the biblical David and William of Orange as a merciful and just leader of the Dutch Revolt, but also between the tyrant King Saul and the Spanish crown, and between the promised land of Israel granted by God to David, and a kingdom granted by God to William.[14]

In the first person, as if quoting himself, William speaks about how his disagreement with his king troubles him; he tries to be faithful to his king,[5] but he is above all faithful to his conscience: to serve God and the Dutch people. Therefore, the last two lines of the first stanza indicate that the leader of the Dutch civil war against the Spanish Empire, of which they were part, had no specific quarrel with king Philip II of Spain, but rather with his emissaries in the Low Countries, such as Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba. This may have been because at the time (late 16th century) it was uncommon to doubt publicly the divine right of kings, who were accountable to God alone.[15] In 1581 the Netherlands nevertheless rejected the legitimacy of the king of Spain's rule over it in the Act of Abjuration.

"Duytschen" (in English generally translated as "Dutch", "native" or Germanic) in the first stanza is a reference to William's roots; its modern Dutch equivalent, "Duits", exclusively means "German", and while it may refer to William's ancestral house (Nassau, Germany) or to the lands of the Holy Roman Empire it is most probably a reference to an older meaning of the word, which can loosely be translated as "Germanic", and seeks to position William as a person with a personal connection with the Low Countries as opposed to the king of Spain, Philip II, who was commonly portrayed as foreign, disconnected and out of touch. In doing so, William is also implicitly comparing himself with the well liked Charles V (Philip's father) who, unlike his son, was born in the Low Countries, spoke Dutch and visited the Low Countries more often than any other part of his realm.[16][17][18][19]

Though only proclaimed the national anthem in 1932, the "Wilhelmus" already had a centuries-old history. It had been sung on many official occasions and at many important events since the outbreak of the Dutch Revolt in 1568, such as the siege of Haarlem in 1573 and the ceremonial entry of the Prince of Orange into Brussels on 18 September 1578.

It has been claimed that during the gruesome torture of Balthasar Gérard (the assassin of William of Orange) in 1584, the song was sung by the guards who sought to overpower Gérard's screams when boiling pigs' fat was poured over him. Gérard allegedly responded "Sing! Dutch sinners! Sing! But know that soon I shall be sung of!".[20]

Another legend claims that following the Navigation Act 1651 (an ordinance by Oliver Cromwell requiring all foreign fleets in the North Sea or the Channel to dip their flag in salute) the "Wilhelmus" was sung (or rather, shouted) by the sailors on the Dutch flagship Brederode in response to the first warning shot fired by an English fleet under Robert Blake, when their captain Maarten Tromp refused to lower his flag. At the end of the song, which coincided with the third and last English warning shot, Tromp fired a full broadside, thereby beginning the Battle of Goodwin Sands and the First Anglo-Dutch War.[20]

During the Dutch Golden Age, it was conceived essentially as the anthem of the House of Orange-Nassau and its supporters – which meant, in the politics of the time, the anthem of a specific political faction which was involved in a prolonged struggle with opposing factions (which sometimes became violent, verging on civil war). Therefore, the fortunes of the song paralleled those of the Orangist faction. Trumpets played the "Wilhelmus" when Prince Maurits visited Breda, and again when he was received in state in Amsterdam in May 1618. When William V arrived in Schoonhoven in 1787, after the authority of the stadholders had been restored, the church bells are said to have played the "Wilhelmus" continuously. After the Batavian Revolution, inspired by the French Revolution, it had come to be called the "Princes' March" as it was banned during the rule of the Patriots, who did not support the House of Orange-Nassau.

However, at the foundation of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1813, the "Wilhelmus" had fallen out of favour. Having become monarchs with a claim to represent the entire nation and stand above factions, the House of Orange decided to break with the song which served them as heads of a faction, and the "Wilhelmus" was replaced by Hendrik Tollens' song Wien Neêrlands bloed door d'aderen vloeit, which was the official Dutch anthem from 1815 until 1932. However, the "Wilhelmus" remained popular and lost its identification as a factional song, and on 10 May 1932, it was decreed that on all official occasions requiring the performance of the national anthem, the "Wilhelmus" was to be played – thereby replacing Tollens' song.

Wilhelmus had a Malay translation of which was sung back when Indonesia was under Dutch colonial rule.[21]

During the German occupation of the Netherlands, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the Nazi Reichskommissar, banned all the emblems of the Dutch royal family, including the "Wilhelmus". It was then taken up by all factions of the Dutch resistance, even those socialists who had previously taken an anti-monarchist stance. The pro-German Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging (NSB), who had sung the "Wilhelmus" at their meetings before the occupation, replaced it with Alle Man van Neerlands Stam ("All Men of Dutch Origin").[22] The anthem was drawn to the attention of the English-speaking world by the 1942 British war film, One of Our Aircraft Is Missing. The film concerns a Royal Air Force bomber crew who are shot down over the occupied Netherlands and are helped to escape by the local inhabitants. The melody is heard during the film as part of the campaign of passive resistance by the population, and it finishes with the coat of arms of the Netherlands on screen while the "Wilhelmus" is played.[23]

The "Wilhelmus" is to be played only once at a ceremony or other event and, if possible, it is to be the last piece of music to be played when receiving a foreign head of state or emissary.

During international sport events, such as the World Cup, UEFA European Football Championship, the Olympic Games and the Dutch Grand Prix, the "Wilhelmus" is also played. In nearly every case the 1st and 6th stanzas (or repeating the last lines), or the 1st stanza alone, are sung/played rather than the entire song, which would result in about 15 minutes of music.[24]

The "Wilhelmus" is also widely used in Flemish nationalist gatherings as a symbol of cultural unity with the Netherlands. Yearly rallies like the "IJzerbedevaart" and the "Vlaams Nationaal Zangfeest" close with singing the 6th stanza, after which the Flemish national anthem "De Vlaamse Leeuw" is sung.

An important set of variations on the melody of "Wilhelmus van Nassouwe" is that by the blind carillon-player Jacob van Eyck in his mid-17th century collection of variations Der Fluyten Lust-hof.[25]

The 10-year old Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed in 1766, while visiting Holland, a set of 7 variations for keyboard in D major on the song, now listed as K. 25.

Richard Strauss wrote his『Variationen über 'Wilhelm von Oraniên'』for military band in 1892. The manuscript which, it seems, was mislaid, is in the Koninklijke Collecties in the Hague. There is a recording available on YouTube by the Band of the Netherlands Royal Marines.

The royal anthemofLuxembourg (called "De Wilhelmus") is a variation on the Wilhelmus. The melody was first used in Luxembourg (at the time in personal union with the Kingdom of the United Netherlands) on the occasion of the visit of the Dutch King and Grand Duke of Luxembourg William III in 1883. Later, the anthem was played for Grand Duke Adolph of Luxembourg along with the national anthem. The melody is very similar, but not identical to that of the "Wilhelmus". It is in official use since 1919.

The song "Wenn alle untreu werden" (German: "If everyone becomes unfaithful") better known as "Das Treuelied", which was written by the poet Max von Schenkendorf (1783–1817) used exactly the same melody as the "Wilhelmus".[citation needed] After the First World War this became extremely popular among German nationalist groups. It became one of the most popular songs of the SS, together with the Horst Wessel song.

The melody is also used in the Swedish folksong "Ack, Göta konungarike [sv]" ("Alas, Gothic kingdom"), written down in 1626. The song deals with the liberation struggle of Sweden under Gustav Vasa in the 16th century.

The "Wilhelmus" was first printed in a geuzenliedboek, literally "Beggars' songbook" in 1581. It used the following text as an introduction to the "Wilhelmus":'[citation needed]

| Een nieuw Christelick Liedt gemaect ter eeren des Doorluchtichsten Heeren, Heere Wilhelm Prince van Oraengien, Grave van Nassou, Patris Patriae, mijnen Genaedigen Forsten ende Heeren. Waer van deerste Capitael letteren van elck veers syner Genaedigen Forstens name metbrengen. Na de wijse van Chartres. | A new Christian song made in the honour of the most noble lord, lord William Prince of Orange, count of Nassau, Pater Patriae (Father of the Nation), my merciful prince and lord. [A song] of which the first capital letter of each stanza form the name of his merciful prince. To the melody of Chartres. |

Original Dutch (1568)[citation needed]

Wilhelmus van Nassouwe

Ben ick van Duytschen bloet

Den Vaderlant getrouwe

Blyf ick tot in den doet:

Een Prince van Oraengien

Ben ick vrij onverveert,

Den Coninck van Hispaengien

Heb ick altijt gheeert.

In Godes vrees te leven

Heb ick altyt betracht,

Daerom ben ick verdreven

Om Landt om Luyd ghebracht:

Maer God sal mij regeren

Als een goet Instrument,

Dat ick zal wederkeeren

In mijnen Regiment.

Lydt u myn Ondersaten

Die oprecht zyn van aert,

Godt sal u niet verlaten

Al zijt ghy nu beswaert:

Die vroom begheert te leven

Bidt Godt nacht ende dach,

Dat hy my cracht wil gheven

Dat ick u helpen mach.

Lyf en goet al te samen

Heb ick u niet verschoont,

Mijn broeders hooch van Namen

Hebbent u oock vertoont:

Graef Adolff is ghebleven

In Vriesland in den slaech,

Syn Siel int ewich Leven

Verwacht den Jongsten dach.

Edel en Hooch gheboren

Van Keyserlicken Stam:

Een Vorst des Rijcks vercoren

Als een vroom Christen man,

Voor Godes Woort ghepreesen

Heb ick vrij onversaecht,

Als een Helt sonder vreesen

Mijn edel bloet ghewaecht.

Mijn Schilt ende betrouwen

Sijt ghy, o Godt mijn Heer,

Op u soo wil ick bouwen

Verlaet mij nimmermeer:

Dat ick doch vroom mach blijven

V dienaer taller stondt,

Die Tyranny verdrijven,

Die my mijn hert doorwondt.

Van al die my beswaren,

End mijn Vervolghers zijn,

Mijn Godt wilt doch bewaren

Den trouwen dienaer dijn:

Dat sy my niet verrasschen

In haren boosen moet,

Haer handen niet en wasschen

In mijn onschuldich bloet.

Als David moeste vluchten

Voor Saul den Tyran:

Soo heb ick moeten suchten

Met menich Edelman:

Maer Godt heeft hem verheven

Verlost uit alder noot,

Een Coninckrijk ghegheven

In Israel seer groot.

Na tsuer sal ick ontfanghen

Van Godt mijn Heer dat soet,

Daer na so doet verlanghen

Mijn Vorstelick ghemoet:

Dat is dat ick mach sterven

Met eeren in dat Velt,

Een eewich Rijck verwerven

Als een ghetrouwe Helt.

Niet doet my meer erbarmen

In mijnen wederspoet,

Dan dat men siet verarmen

Des Conincks Landen goet,

Dat van de Spaengiaerts crencken

O Edel Neerlandt soet,

Als ick daer aen ghedencke

Mijn Edel hert dat bloet.

Als een Prins op gheseten

Met mijner Heyres cracht,

Van den Tyran vermeten

Heb ick den Slach verwacht,

Die by Maestricht begraven

Bevreesden mijn ghewelt,

Mijn ruyters sach men draven.

Seer moedich door dat Velt.

Soo het den wille des Heeren

Op die tyt had gheweest,

Had ick gheern willen keeren

Van v dit swear tempeest:

Maer de Heer van hier boven

Die alle dinck regeert.

Diemen altijd moet loven

En heeftet niet begheert.

Seer Christlick was ghedreven

Mijn Princelick ghemoet,

Stantvastich is ghebleven

Mijn hert in teghenspoet,

Den Heer heb ick ghebeden

Van mijnes herten gront,

Dat hy mijn saeck wil reden,

Mijn onschult doen bekant.

Oorlof mijn arme Schapen

Die zijt in grooten noot,

V Herder sal niet slapen

Al zijt ghy nu verstroyt:

Tot Godt wilt v begheven,

Syn heylsaem Woort neemt aen,

Als vrome Christen leven,

Tsal hier haest zijn ghedaen.

Voor Godt wil ick belijden

End zijner grooter Macht,

Dat ick tot gheenen tijden

Den Coninck heb veracht:

Dan dat ick Godt den Heere

Der hoochster Maiesteyt,

Heb moeten obedieren,

Inder gherechticheyt.

Acrostic

WILLEM VAN NASSOV

Contemporary Dutch

Wilhelmus van Nassouwe

ben ik, van Duitsen bloed,

den vaderland getrouwe

blijf ik tot in den dood.

Een Prinse van Oranje

ben ik, vrij onverveerd,

den Koning van Hispanje

heb ik altijd geëerd.

In Godes vrees te leven

heb ik altijd betracht,

daarom ben ik verdreven,

om land, om luid gebracht.

Maar God zal mij regeren

als een goed instrument,

dat ik zal wederkeren

in mijnen regiment.

Lijdt u, mijn onderzaten

die oprecht zijt van aard,

God zal u niet verlaten,

al zijt gij nu bezwaard.

Die vroom begeert te leven,

bidt God nacht ende dag,

dat Hij mij kracht wil geven,

dat ik u helpen mag.

Lijf en goed al te samen

heb ik u niet verschoond,

mijn broeders hoog van namen

hebben 't u ook vertoond:

Graaf Adolf is gebleven

in Friesland in de slag,

zijn ziel in 't eeuwig leven

verwacht de jongste dag.

Edel en hooggeboren,

van keizerlijke stam,

een vorst des rijks verkoren,

als een vroom christenman,

voor Godes woord geprezen,

heb ik, vrij onversaagd,

als een held zonder vreze

mijn edel bloed gewaagd.

Mijn schild ende betrouwen

zijt Gij, o God mijn Heer,

op U zo wil ik bouwen,

verlaat mij nimmermeer.

Dat ik doch vroom mag blijven,

uw dienaar t'aller stond,

de tirannie verdrijven

die mij mijn hart doorwondt.

Van al die mij bezwaren

en mijn vervolgers zijn,

mijn God, wil doch bewaren

de trouwe dienaar dijn,

dat zij mij niet verrassen

in hunne boze moed,

hun handen niet en wassen

in mijn onschuldig bloed.

Als David moeste vluchten

voor Sauel den tiran,

zo heb ik moeten zuchten

als menig edelman.

Maar God heeft hem verheven,

verlost uit alder nood,

een koninkrijk gegeven

in Israël zeer groot.

Na 't zuur zal ik ontvangen

van God mijn Heer het zoet,

daarnaar zo doet verlangen

mijn vorstelijk gemoed:

dat is, dat ik mag sterven

met ere in dat veld,

een eeuwig rijk verwerven

als een getrouwe held.

Niets doet mij meer erbarmen

in mijne wederspoed

dan dat men ziet verarmen

des Konings landen goed.

Dat u de Spanjaards krenken,

o edel Neerland zoet,

als ik daaraan gedenke,

mijn edel hart dat bloedt.

Als een prins opgezeten

met mijner heireskracht,

van de tiran vermeten

heb ik de slag verwacht,

die, bij Maastricht begraven,

bevreesden mijn geweld;

mijn ruiters zag men draven

zeer moedig door dat veld.

Zo het de wil des Heren

op die tijd was geweest,

had ik geern willen keren

van u dit zwaar tempeest.

Maar de Heer van hierboven,

die alle ding regeert,

die men altijd moet loven,

Hij heeft het niet begeerd.

Zeer christlijk was gedreven

mijn prinselijk gemoed,

standvastig is gebleven

mijn hart in tegenspoed.

De Heer heb ik gebeden

uit mijnes harten grond,

dat Hij mijn zaak wil redden,

mijn onschuld maken kond.

Oorlof, mijn arme schapen

die zijt in grote nood,

uw herder zal niet slapen,

al zijt gij nu verstrooid.

Tot God wilt u begeven,

zijn heilzaam woord neemt aan,

als vrome christen leven,—

't zal hier haast zijn gedaan.

Voor God wil ik belijden

en zijne grote macht,

dat ik tot gene tijden

de Koning heb veracht,

dan dat ik God de Here,

de hoogste Majesteit,

heb moeten obediëren

in de gerechtigheid.

WILLEM VAN NAZZOV

Official free translation[26]

William of Nassau, scion

Of a Dutch and ancient line,

I dedicate undying

Faith to this land of mine.

A prince I am, undaunted,

Of Orange, ever free,

To the king of Spain I've granted

A lifelong loyalty.

I've ever tried to live in

The fear of God's command

And therefore I've been driven,

From people, home, and land,

But God, I trust, will rate me

His willing instrument

And one day reinstate me

Into my government.

Let no despair betray you,

My subjects true and good.

The Lord will surely stay you

Though now you are pursued.

He who would live devoutly

Must pray God day and night

To throw His power about me

As champion of your right.

Life and my all for others

I sacrificed, for you!

And my illustrious brothers

Proved their devotion too.

Count Adolf, more's the pity,

Fell in the Frisian fray,

And in the eternal city

Awaits the judgement day.

I, nobly born, descended

From an imperial stock.

An empire's prince, defended

(Braving the battle's shock

Heroically and fearless

As pious Christian ought)

With my life's blood the peerless

Gospel of God our Lord.

A shield and my reliance,

O God, Thou ever wert.

I'll trust unto Thy guidance.

O leave me not ungirt.

That I may stay a pious

Servant of Thine for aye

And drive the plagues that try us

And tyranny away.

My God, I pray thee, save me

From all who do pursue

And threaten to enslave me,

Thy trusted servant true.

O Father, do not sanction

Their wicked, foul design,

Don't let them wash their hands in

This guiltless blood of mine.

O David, thou soughtest shelter

From King Saul's tyranny.

Even so I fled this welter

And many a lord with me.

But God the Lord did save me

From exile and its hell

And, in His mercy, gave him

A realm in Israel.

Fear not 't will rain sans ceasing

The clouds are bound to part.

I bide that sight so pleasing

Unto my princely heart,

Which is that I with honor

Encounter death in war,

And meet in heaven my Donor,

His faithful warrior.

Nothing so moves my pity

As seeing through these lands,

Field, village, town and city

Pillaged by roving hands.

O that the Spaniards rape thee,

My Netherlands so sweet,

The thought of that does grip me

Causing my heart to bleed.

A stride on steed of mettle

I've waited with my host

The tyrant's call to battle,

Who durst not do his boast.

For, near Maastricht ensconced,

He feared the force I wield.

My horsemen saw one bounce it

Bravely across the field.

Surely, if God had willed it,

When that fierce tempest blew,

My power would have stilled it,

Or turned its blast from you

But He who dwells in heaven,

Whence all our blessings flow,

For which aye praise be given,

Did not desire it so.

Steadfast my heart remaineth

In my adversity

My princely courage straineth

All nerves to live and be.

I've prayed the Lord my Master

With fervid heart and tense

To save me from disaster

And prove my innocence.

Alas! my flock. To sever

Is hard on us. Farewell.

Your Shepherd wakes, wherever

Dispersed you may dwell,

Pray God that He may ease you.

His Gospel be your cure.

Walk in the steps of Jesu

This life will not endure.

Unto the Lord His power

I do confession make

That ne'er at any hour

Ill of the King I spake.

But unto God, the greatest

Of Majesties I owe

Obedience first and latest,

For Justice wills it so.

WILLIAM OF NASSAU

IPA transcription of the first and sixth stanzas[a]

[ʋɪɫ.ˈɦɛɫ.mʏs vɑn nɑ.ˈsɑu̯.ø]

[bɛn ɪk vɑn ˈdœy̯t.sən blut]

[dɛn ˈvaː.dør.ˌɫɑnt ɣø.ˈtrɑu̯.ø]

[blɛi̯v ɪk tɔt ɪn dɛn doː(w)t]

[ən ˈprɪn.sø vɑn ˌoː(w).ˈrɑn.jø]

[bɛn ɪk frɛi̯ ˌɔn.vør.ˈveːrt]

[dɛn ˈkoː(w).nɪŋ vɑn ɦɪs.ˈspɑn.jø]

[ɦɛp ɪk ˈɑɫ.tɛi̯t ɣø.ˈeːrt]

[mɛi̯n sxɪɫt ˈɛn.dø bø.ˈtrɑu̯.ən]

[ˈzɛi̯t ɣɛi̯ oː(w) ɣɔt mɛi̯n ɦeːr]

[ɔp y zoː(w) ʋɪl ɪk ˈbɑu̯.ən]

[vər.ˈlaːt mɛi̯ ˌnɪ.mør.ˈmeːr]

[dɑt ɪk dɔx froː(w)m mɑɣ ˈblɛi̯.vən]

[yu̯ ˈdi.naːr ˈtɑ.lør stɔnt]

[dø ˌti.rɑ.ˈni vər.ˈdrɛi̯.vən]

[di mɛi̯ mɛi̯n ɦɑrt ˈdoːr.ʋɔnt]