Amir Khusrau

| |

|---|---|

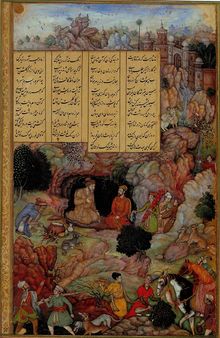

Amir Khusrow teaching his disciples in a miniature from a manuscript of Majlis al-Ushshaq by Husayn Bayqarah.

| |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Ab'ul Hasan Yamīn ud-Dīn K͟husrau |

| Born | 1253 Patiyali, Delhi Sultanate |

| Died | October 1325 (aged 71-72) Delhi, Delhi Sultanate |

| Genres | Ghazal, Qawwali, Ruba'i, Tarana |

| Occupation(s) | Sufi, musician, poet, composer, author, scholar |

Ab'ul Hasan Yamīn ud-Dīn Khusrau (1253 – 1325) (Urdu: ابوالحسن یمینالدین خسرو, Hindi: अमीर ख़ुसरो), better known as Amīr Khusrow Dehlavī, was a Sufi musician, poet and scholar from the Indian subcontinent. He was an iconic figure in the cultural history of the Indian subcontinent. He was a mystic and a spiritual disciple of Nizamuddin AuliyaofDelhi. He wrote poetry primarily in Persian, but also in Hindavi. A vocabulary in verse, the Ḳhāliq Bārī, containing Arabic, Persian, and Hindavi terms is often attributed to him.[1] Khusrow is sometimes referred to as the "voice of India" (Tuti-e-Hind), and has been called the "father of Urdu literature."[2][3][4][5]

Khusrow is regarded as the "father of qawwali" (a devotional music form of the Sufis in the Indian subcontinent), and introduced the ghazal style of song into India, both of which still exist widely in India and Pakistan.[6][7] Khusrow was an expert in many styles of Persian poetry which were developed in medieval Persia, from Khāqānī's qasidastoNizami's khamsa. He used 11 metrical schemes with 35 distinct divisions. He wrote in many verse forms including ghazal, masnavi, qata, rubai, do-baiti and tarkib-band. His contribution to the development of the ghazal was significant.[8]

Amīr Khusrow was born in 1253 at Patiyali near Etah in modern-day Uttar Pradesh, India, in what was then the Delhi Sultanate, the son of Amīr Saif ud-Dīn Mahmūd, a man of Turkic extraction, by his Indian Rajput wife.

Amīr Khusrow's father, Amīr Saif ud-Dīn Mahmūd, was born a member of the Lachin tribe of Transoxania, themselves belonging to the Kara-Khitai set of Turkic tribes.[8][9][10] He belonged to Kesh, a small town near Samarkhand in what is now Uzbekistan, and that is where he grew up. When he was a young man, that country was despoiled and ravaged by Genghis Khan's invasion of Central Asia, and much of the population fled to other lands, India being a favored destination. Amir Saif ud-Din migrated from his hometown of KeshtoBalkh (now in northern Afghanistan), which was a relatively safe place; from here, they sent representations seeking refuge and succour to the Sultan of distant Delhi. This was granted, and the group then travelled to Delhi. Sultan Shams ud-Din Iltutmish, ruler of Delhi, was himself a Turk like them; indeed, he had been raised in the same region of central Asia, and had undergone somewhat similar circumstances in earlier life. He not only welcomed the refugees to his court but also granted high offices and landed estates to some of them. Iltutmish provided shelter and lavish patronage to exiled princes, artisans, scholars and rich nobles. In 1230, Amir Saif ud-Din was granted a fief in the district of Patiyali.

Amir Saif ud-Din married Bibi Daulatnaz, the daughter of Rawat Arz, a Hindu of the Rajput caste who was the famous war minister of Ghiyas ud-Din Balban, the ninth Sultan of Delhi. Daulatnaz's family belonged to the Rajput community of modern-day Uttar Pradesh.[10][11]

Amir Saif ud-Din and his Rajput-born Indian wife Bibi Daulatnaz became the parents of four children: three sons (one of whom was Khusrow) and a daughter. Amir Saif ud-Din Mahmud died in 1260, when Khusrow was only seven years old. After the death of her husband, Khusrow's mother moved back to her father's house in Delhi with her children. It was thus in the house of his Rajput maternal grandfather, Rawat Arz (known by his title as Imad-ul-Mulk), that Khusrow was raised. He thus grew up very close to the culture and traditions of Indian society, and was not alienated from real Indian society in the way that the ruling Turkic classes may have been. He grew up rooted in his environment, and not hankering after some foreign land. Over and over again in his poetry, and throughout his life, he affirmed that he was Indian and nothing else ("I have not the noteds of Misrorfars he says).

Khusrow was an intelligent child. He started learning and writing poetry at the age of eight. His first divan, Tuhfat us-Sighr (The Gift of Childhood), containing poems composed between the ages of 16 and 18, was compiled in 1271. In 1273, when Khusrow was 20 years old, his grandfather, who was reportedly 113 years old, died.

After Khusrow's grandfather's death, Khusrow joined the army of Malik Chajju, a nephew of the reigning Sultan, Ghiyas ud-Din Balban. This brought his poetry to the attention of the Assembly of the Royal Court where he was honored.

Nasir ud-Din Bughra Khan, the second son of Balban, was invited to listen to Khusrow. He was impressed and became Khusrow's patron in 1276. In 1277 Bughra Khan was then appointed ruler of Bengal, and Khusrow visited him in 1279 while writing his second divan, Wast ul-Hayat (The Middle of Life). Khusrow then returned to Delhi. Balban's eldest son, Khan Muhammad (who was in Multan), arrived in Delhi, and when he heard about Khusrow he invited him to his court. Khusrow then accompanied him to Multan in 1281. Multan at the time was the gateway to India and was a center of knowledge and learning. Caravans of scholars, tradesmen and emissaries transited through Multan from Baghdad, Arabia and Persia on their way to Delhi. Khusrow wrote that:

I tied the belt of service on my waist and put on the cap of companionship for another five years. I imparted lustre to the water of Multan from the ocean of my wits and pleasantries.

On 9 March 1285, Khan Muhammad was killed in battle while fighting Mongols who were invading the Sultanate. Khusrow wrote two elegies in grief of his death. In 1287, Khusrow travelled to Awadh with another of his patrons, Amir Ali Hatim. At the age of eighty, Balban called his second son Bughra Khan back from Bengal, but Bughra Khan refused. After Balban's death in 1287, his grandson Muiz ud-Din Qaiqabad, Bughra Khan's son, was made the Sultan of Delhi at the age of 17. Khusrow remained in Qaiqabad's service for two years, from 1287 to 1288. In 1288 Khusrow finished his first masnavi, Qiran us-Sa'dain (Meeting of the Two Auspicious Stars), which was about Bughra Khan meeting his son Muiz ud-Din Qaiqabad after a long enmity. After Qaiqabad suffered a stroke in 1290, nobles appointed his three-year-old son Shams ud-Din Kayumars as Sultan. A Turk named Jalal ud-Din Firuz Khalji then marched on Delhi, killed Qaiqabad and became Sultan, thus ending the Mamluk dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate and starting the Khalji dynasty.

Jalal ud-Din Firuz Khalji appreciated poetry and invited many poets to his court. Khusrow was honoured and respected in his court and was given the title "Amir". He was given the job of "Mushaf-dar". Court life made Khusrow focus more on his literary works. Khusrow's ghazals which he composed in quick succession were set to music and were sung by singing girls every night before the Sultan. Khusrow writes about Jalal ud-Din Firuz:

The King of the world Jalal ud-Din, in reward for my infinite pain which I undertook in composing verses, bestowed upon me an unimaginable treasure of wealth.

In 1290 Khusrow completed his second masnavi, Miftah ul-Futuh (Key to the Victories), in praise of Jalal ud-Din Firuz's victories. In 1294 Khusrow completed his third divan, Ghurrat ul-Kamaal (The Prime of Perfection), which consisted of poems composed between the ages of 34 and 41.

After Jalal ud-Din Firuz, Ala ud-Din Khalji ascended to the throne of Delhi in 1296. Khusrow wrote the Khaza'in ul-Futuh (The Treasures of Victory) recording Ala ud-Din's construction works, wars and administrative services. He then composed a khamsa (quintet) with five masnavis, known as Khamsa-e-Khusrow (Khamsa of Khusrow), completing it in 1298. The khamsa emulated that of the earlier poet of Persian epics, Nizami Ganjavi. The first masnavi in the khamsa was Matla ul-Anwar (Rising Place of Lights) consisting of 3310 verses (completed in 15 days) with ethical and Sufi themes. The second masnavi, Khusrow-Shirin, consisted of 4000 verses. The third masnavi, Laila-Majnun, was a romance. The fourth voluminous masnavi was Aina-e-Sikandari, which narrated the heroic deeds of Alexander the Great in 4500 verses. The fifth masnavi was Hasht-Bihisht, which was based on legends about Bahram V, the fifteenth king of the Sasanian Empire. All these works made Khusrow a leading luminary in the world of poetry. Ala ud-Din Khalji was highly pleased with his work and rewarded him handsomely. When Ala ud-Din's son and future successor Qutb ud-Din Mubarak Shah Khalji was born, Khusrow prepared the horoscope of Mubarak Shah Khalji in which certain predictions were made. This horoscope is included in the masnavi Saqiana.[12]

In 1300, when Khusrow was 47 years old, his mother and brother died. He wrote these lines in their honour:

A double radiance left my star this year

Gone are my brother and my mother,

My two full moons have set and ceased to shine

In one short week through this ill-luck of mine.

Khusrow's homage to his mother on her death was:

Where ever the dust of your feet is found is like a relic of paradise for me.

In 1310 Khusrow became close to a Sufi saint of the Chishti Order, Nizamuddin Auliya. In 1315, Khusrow completed the romantic masnavi Duval Rani - Khizr Khan (Duval Rani and Khizr Khan), about the marriage of the Vaghela princess Duval Rani to Khizr Khan, one of Ala ud-Din Khalji's sons.

After Ala ud-Din Khalji's death in 1316, his son Qutb ud-Din Mubarak Shah Khalji became the Sultan of Delhi. Khusrow wrote a masnavi on Mubarak Shah Khalji called Nuh Sipihr (Nine Skies), which described the events of Mubarak Shah Khalji's reign. He classified his poetry in nine chapters, each part of which is considered a "sky". In the third chapter he wrote a vivid account of India and its environment, seasons, flora and fauna, cultures, scholars, etc. He wrote another book during Mubarak Shah Khalji's reign by name of Ijaz-e-Khusravi (The Miracles of Khusrow), which consisted of five volumes. In 1317 Khusrow compiled Baqia-Naqia (Remnants of Purity). In 1319 he wrote Afzal ul-Fawaid (Greatest of Blessings), a work of prose that contained the teachings of Nizamuddin Auliya.

In 1320 Mubarak Shah Khalji was killed by Khusro Khan, who thus ended the Khalji dynasty and briefly became Sultan of Delhi. Within the same year, Khusro Khan was captured and beheaded by Ghiyath al-Din Tughlaq, who became Sultan and thus began the Tughlaq dynasty. In 1321 Khusrow began to write a historic masnavi named Tughlaq Nama (Book of the Tughlaqs) about the reign of Ghiyath al-Din Tughlaq and that of other Tughlaq rulers.

Khusrow died in October 1325, six months after the death of Nizamuddin Auliya. Khusrow's tomb is next to that of his spiritual master in the Nizamuddin Dargah in Delhi.[13] Nihayat ul-Kamaal (The Zenith of Perfection) was compiled probably a few weeks before his death.

Khusrow is credited with fusing the Persian, Arabic, Turkish, and Indian musical traditions in the late 13th century to create qawwali, a form of Sufi devotional music. Qaul (Arabic: ) is an "utterance", Qawwāl is someone who often repeats (sings) a Qaul, and Qawwāli is what a Qawwāl sings. The word sama is often still used in Central Asia and Turkey to refer to forms very similar to qawwali.

Amir Khusrow was a prolific classical poet associated with the royal courts of more than seven rulers of the Delhi Sultanate. He wrote many playful riddles, songs and legends which have become a part of popular culture in South Asia. His riddles are one of the most popular forms of Hindavi poetry today.[14] It is a genre that involves double entendre or wordplay.[14] Innumerable riddles by the poet have been passed through oral tradition over the last seven centuries.[14] Through his literary output, Khusrow represents one of the first recorded Indian personages with a true multicultural or pluralistic identity. Musicians credit Khusrau with the creation of six styles of music: qaul, qalbana, naqsh, gul, tarana and khyal, but there is insufficient evidence for this.[15][16]

Amir Khusro’s putative associations with the Tarana run much deeper. One of the most persistent legends of Hindustani music relates to the encounter between Amir Khusro, who was then associated with the court of emperor Allauddin Khalji, and Gopal Nayak, court-musician to the king of Devagiri. Allauddin commanded Gopal Nayak to present the Raga Kadambak for six evenings running. During the entire performance, Khusro lay concealed under the emperor’s throne, and stealthily absorbed all that the Nayak had sung. On the seventh day, he astonished everyone present in the court by reproducing all that Gopal Nayak had presented. However, since he couldn’t follow the Nayak’s language, he substituted the text of the compositions with meaningless syllables. And that is how the Tarana was born! (Willard 1834: 121) [17]

Khusrow wrote primarily in Persian. Many Hindustani (historically known as Hindavi) verses are attributed to him, although there is no evidence for their composition by Khusrow before the 18th century.[18][19] The language of the Hindustani verses appear to be relatively modern. He also wrote a war ballad in Punjabi.[20] In addition, he spoke Arabic and Sanskrit.[10][21][22][23][24][25][26] His poetry is still sung today at Sufi shrines throughout Pakistan and India.

In 1976 the renowned Pakistani musician Khurshid Anwar played a key role in observing the 700th birth anniversary of Amir Khusrow. Since he was also a musicologist, he wrote one of his rare music articles on Amir Khusrow, "A gift to posterity". In addition, he actively planned music events and activities throughout 1976. In Pakistan, Anwar had also been praised for his efforts to keep alive classical music not only through his many film compositions in Pakistan, but also through his unique collection of classical music performances recorded by EMI Pakistan, known as Aahang-e-Khusravi in two parts in 1978. The second part of the Aahang-e-Khusravi recordings was known as Gharanon Ki Gaiyki which consisted of audio recordings of representatives of the main gharanas of classical singers in Pakistan on 20 audio cassettes. All this was meant to be a tribute to Amir Khusrow.[27]

Inscribed in the top terrace of the Shalimar Bagh, Srinagar (now in Jammu and Kashmir, India), are some famous phrases in Persian, which are sometimes attributed to Khusrow, although are not found in any of his written works:

Agar Firdaus bar ru-ye zamin ast,

Hamin ast o hamin ast o hamin ast.

In English: "If there is a paradise on earth, it is this, it is this, it is this."[28][29][30] This verse is also found on several Mughal structures, supposedly in reference to Kashmir.[31]

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter |deadurl= ignored (|url-status= suggested) (help)

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Academics |

|

| Artists |

|

| People |

|

| Other |

|