|

m Reverted edits by 49.150.13.226 (talk) (HG) (3.4.12)

|

|

||

| (45 intermediate revisions by 27 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Filipino general and scientist (1866–1899)}} |

{{Short description|Filipino general and scientist (1866–1899)}} |

||

{{About|the Filipino general|the Spanish footballer|Antonio Luna (footballer)|the Philippine Navy ship|BRP Gen. Antonio Luna (PG-141){{!}}BRP ''Gen. Antonio Luna'' (PG-141)}} |

{{About|the Filipino general|the Spanish footballer|Antonio Luna (footballer)|the Philippine Navy ship|BRP Gen. Antonio Luna (PG-141){{!}}BRP ''Gen. Antonio Luna'' (PG-141)}} |

||

{{ |

{{Family name hatnote|Luna|Novicio|lang=Spanish}} |

||

{{Use Philippine English|date=March 2023}} |

{{Use Philippine English|date=March 2023}} |

||

{{Use mdy dates|date=June |

{{Use mdy dates|date=June 2024}} |

||

{{Infobox officeholder |

{{Infobox officeholder |

||

| name = Antonio Luna |

| name = Antonio Luna |

||

| image = Antonio luna small.jpg |

| image = Antonio luna small.jpg |

||

| image_size = |

| image_size = |

||

| office = [[Chief of the Army (Philippines)|Commanding General of the Philippine Revolutionary Army]] |

| office = [[Chief of the Army (Philippines)|Commanding General]] of the [[Philippine Revolutionary Army]] |

||

| predecessor = [[Artemio Ricarte]] |

| predecessor = [[Artemio Ricarte]] |

||

| successor = [[Emilio Aguinaldo]] |

| successor = [[Emilio Aguinaldo]] |

||

| president = Emilio Aguinaldo |

| president = [[Emilio Aguinaldo]] |

||

| term_start = |

| term_start = March 28, 1899 |

||

| term_end = June 5, 1899 |

| term_end = June 5, 1899 |

||

| nickname = {{Plainlist| |

| nickname = {{Plainlist| |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

| birth_name = Antonio Narciso Luna de San Pedro y Novicio Ancheta |

| birth_name = Antonio Narciso Luna de San Pedro y Novicio Ancheta |

||

| birth_date = {{Birth date|1866|10|29}} |

| birth_date = {{Birth date|1866|10|29}} |

||

| birth_place = [[San Nicolas |

| birth_place = [[San Nicolas, Manila]], [[Captaincy General of the Philippines]], Spanish Empire |

||

| death_date = {{Death date and age|1899|6|5|1866|10|29}} |

| death_date = {{Death date and age|1899|6|5|1866|10|29}} |

||

| death_place = [[Cabanatuan]], Nueva Ecija, {{awrap|First Philippine Republic}} |

| death_place = [[Cabanatuan]], Nueva Ecija, {{awrap|First Philippine Republic}} |

||

| Line 28: | Line 28: | ||

| branch = [[Philippine Revolutionary Army]] |

| branch = [[Philippine Revolutionary Army]] |

||

| serviceyears = 1898–1899 |

| serviceyears = 1898–1899 |

||

| rank = [[ |

| rank = [[Image:PR Teniente General SE.svg|25px|General]] Captain General |

||

| commands = <!--Military service--> |

| commands = <!--Military service--> |

||

| battles = {{tree list}} |

| battles = {{tree list}} |

||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

* [[Joaquin Luna]] (brother) |

* [[Joaquin Luna]] (brother) |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| office1 = Assistant Secretary of War and Supreme Commander of the Republican Army |

|||

| office2 = Chief of War Operations |

|||

| termstart1 = September 28, 1898 |

|||

| termend1 = March 1, 1899 |

|||

| termend2 = September 28, 1898 |

|||

| termstart2 = September 26, 1898 |

|||

| president1 = [[Emilio Aguinaldo]] |

|||

| president2 = [[Emilio Aguinaldo]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Antonio Narciso Luna de San Pedro y Novicio Ancheta''' ({{IPA-es|anˈtonjo ˈluna|lang}}; October 29, 1866 – June 5, 1899) was a [[Filipinos|Filipino]] army general who fought in the [[Philippine–American War]] before his assassination |

'''Antonio Narciso Luna de San Pedro y Novicio Ancheta''' ({{IPA-es|anˈtonjo ˈluna|lang}}; October 29, 1866 – June 5, 1899) was a [[Filipinos|Filipino]] pharmacist and army general who fought in the [[Philippine–American War]] before his assassination on June 5, 1899, at the age of 32.<ref>{{cite news |title=GENERAL LUNA IS MURDERED BY AGUINALDO |url=https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=SFC18990614.2.2.4&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN-------- |access-date=June 5, 2023 |work=San Francisco Call}}</ref><ref name="Pantaleon Garcia" /> |

||

Regarded as one of the fiercest generals of his time, he succeeded [[Artemio Ricarte]] as the [[Chief of the Army (Philippines)|Commanding General of the Philippine Army]]. He sought to apply his background in military science to the fledgling army. A sharpshooter himself, he organized professional guerrilla soldiers later named the "[[Luna Sharpshooters]]" and the "Black Guard" with Senyor Michael Joaquin. His three-tier defense, now known as the Luna Defense Line, gave the American troops a difficult endeavor during their campaign in the provinces north of [[Manila]]. This defense line culminated in the creation of a military stronghold in the [[Cordillera Central, Luzon|Cordillera]].<ref name="FM" />{{page needed|date=September 2022}} |

Regarded as one of the fiercest generals of his time, he succeeded [[Artemio Ricarte]] as the [[Chief of the Army (Philippines)|Commanding General of the Philippine Army]]. He sought to apply his background in military science to the fledgling army. A sharpshooter himself, he organized professional guerrilla soldiers later named the "[[Luna Sharpshooters]]" and the "Black Guard" with Senyor Michael Joaquin. His three-tier defense, now known as the Luna Defense Line, gave the American troops a difficult endeavor during their campaign in the provinces north of [[Manila]]. This defense line culminated in the creation of a military stronghold in the [[Cordillera Central, Luzon|Cordillera]].<ref name="FM" />{{page needed|date=September 2022}} |

||

Despite his commitment to discipline the army and serve the Republic which attracted the admiration of people, his temper and fiery outlashes caused some to abhor him, including people from [[List of cabinets of the Philippines#Emilio Aguinaldo (1899–1901)| |

Despite his commitment to discipline the army and serve the Republic which attracted the admiration of the people, his temper and fiery outlashes caused some to abhor him, including people from Aguinaldo's [[List of cabinets of the Philippines#Emilio Aguinaldo (1899–1901)|cabinet]].<ref name="Agoncillo 8th" /> Nevertheless, Luna's efforts were recognized during his time, and he was awarded the [[List of medals for bravery|Philippine Republic Medal]] in 1899. He was also a member of the [[Revolutionary Government of the Philippines (1898–1899)#The Malolos Revolutionary Congress|Malolos Congress]].<ref name="Jose1972p450" /> Besides his military studies, Luna also studied [[pharmacology]], literature, and [[chemistry]].<ref name="Dumindin 2006" /> |

||

== |

==Family background== |

||

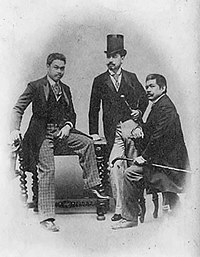

[[File:Antonio and Juan Luna.jpg|thumb|left|Luna (left) and brother [[Juan Luna]]]] |

[[File:Antonio and Juan Luna.jpg|thumb|left|Luna (left) and brother [[Juan Luna]]]] |

||

| Line 58: | Line 66: | ||

===Siblings=== |

===Siblings=== |

||

His older brother, [[Juan Luna|Juan]], was an accomplished painter who studied in the [[Madrid]] [[Escuela de Bellas Artes de San Fernando]]. His [[Spoliarium]] garnered one of the three gold medals awarded in the [[Madrid]] ''Exposición Nacional de Bellas Artes'' in 1884. Another brother, José, became a doctor.<ref name="PS 2008" /> Yet another brother, [[Joaquin Luna|Joaquín]], fought with Antonio in the [[Philippine–American War]],<ref name="Jose1972p372" /> and later served as governor of [[La Union]] from 1904 to 1907.<ref name="5sWQm" /> Joaquín would also serve as a senator from 1916 to 1919.<ref name="ROWuG" /> His three other siblings were Numeriana, Manuel, and Remedios.<ref name="historybehindmovie9" /> |

His older brother, [[Juan Luna|Juan]], was an accomplished painter who studied in the [[Madrid]] [[Escuela de Bellas Artes de San Fernando]]. His ''[[Spoliarium]]'' garnered one of the three gold medals awarded in the [[Madrid]] ''Exposición Nacional de Bellas Artes'' in 1884. Another brother, José, became a doctor.<ref name="PS 2008" /> Yet another brother, [[Joaquin Luna|Joaquín]], fought with Antonio in the [[Philippine–American War]],<ref name="Jose1972p372" /> and later served as governor of [[La Union]] from 1904 to 1907.<ref name="5sWQm" /> Joaquín would also serve as a senator from 1916 to 1919.<ref name="ROWuG" /> His three other siblings were Numeriana, Manuel, and Remedios.<ref name="historybehindmovie9" /> |

||

== |

==Education== |

||

[[File: Antonio Luna with Sala de Armas students.png|thumb|left|Luna (sitting, 2nd from left) and some of his scholars of Sala de Armas, a [[fencing]] club which was located in [[Sampaloc, Manila]]]] |

[[File: Antonio Luna with Sala de Armas students.png|thumb|left|Luna (sitting, 2nd from left) and some of his scholars of Sala de Armas, a [[fencing]] club which was located in [[Sampaloc, Manila]]]] |

||

| Line 67: | Line 75: | ||

After his education under Maestro Intong, he studied at the [[Ateneo de Manila University|Ateneo Municipal de Manila]], where he received a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1881.<ref name="historybehindmovie10" /> He went on to study literature and chemistry at the [[University of Santo Tomas]], where he won first prize for a paper in chemistry titled ''Two Fundamental Bodies of Chemistry'' (''Dos Cuerpos fundamentales de la Quimica''). He also studied Pharmacy. Meanwhile, his background in swordsmanship, fencing, and military tactics came from his studies under Don Martin Cartagena, a major in the Spanish Army.<ref name="historybehindmovie10" /> In addition, he acquired the skill to become a sharpshooter. Upon the invitation of his elder brother [[Juan Luna|Juan]] in 1890, Antonio was sent by his parents to Spain. There he acquired a licentiate (at [[Universidad de Barcelona]]) and doctorate (at [[Universidad Central de Madrid]]).<ref name="Dumindin 2006" /> |

After his education under Maestro Intong, he studied at the [[Ateneo de Manila University|Ateneo Municipal de Manila]], where he received a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1881.<ref name="historybehindmovie10" /> He went on to study literature and chemistry at the [[University of Santo Tomas]], where he won first prize for a paper in chemistry titled ''Two Fundamental Bodies of Chemistry'' (''Dos Cuerpos fundamentales de la Quimica''). He also studied Pharmacy. Meanwhile, his background in swordsmanship, fencing, and military tactics came from his studies under Don Martin Cartagena, a major in the Spanish Army.<ref name="historybehindmovie10" /> In addition, he acquired the skill to become a sharpshooter. Upon the invitation of his elder brother [[Juan Luna|Juan]] in 1890, Antonio was sent by his parents to Spain. There he acquired a licentiate (at [[Universidad de Barcelona]]) and doctorate (at [[Universidad Central de Madrid]]).<ref name="Dumindin 2006" /> |

||

=== |

===Scientific achievements=== |

||

[[File:Antonio Luna at Institut Pasteur in Paris.jpg|thumb|Antonio Luna poses with a microscope at the Institut Pasteur in Paris.]] |

[[File:Antonio Luna at Institut Pasteur in Paris.jpg|thumb|Antonio Luna poses with a microscope at the Institut Pasteur in Paris.]] |

||

Luna was active as a researcher in the scientific community. After receiving his doctorate in 1893, he published a scientific treatise on malaria entitled ''On Malarial Pathology'' (''El Hematozoario del Paludismo''), which was favorably received in the scientific community.<ref name="historybehindmovie12" /> He then went to Belgium and France and worked as an assistant to Dr. Latteaux at the [[Pasteur Institute]] and to Dr. Laffen. In recognition of his ability, he was commissioned by the Spanish government to study tropical and communicable diseases.<ref name="Dumindin 2006" /> In 1894, he returned to the Philippines where he took part in an examination to determine who would become the chief chemist of the Municipal Laboratory of Manila. Luna came in first and won the position.<ref name="PS 2008" /> |

Luna was active as a researcher in the scientific community. After receiving his doctorate in 1893, he published a scientific treatise on malaria entitled ''On Malarial Pathology'' (''El Hematozoario del Paludismo''), which was favorably received in the scientific community.<ref name="historybehindmovie12" /> He then went to Belgium and France and worked as an assistant to Dr. Latteaux at the [[Pasteur Institute]] and to Dr. Laffen. In recognition of his ability, he was commissioned by the Spanish government to study tropical and communicable diseases.<ref name="Dumindin 2006" /> In 1894, he returned to the Philippines where he took part in an examination to determine who would become the chief chemist of the Municipal Laboratory of Manila. Luna came in first and won the position.<ref name="PS 2008" /> |

||

== |

==Propaganda Movement== |

||

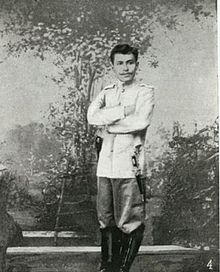

[[File:Antonio Luna, Eduardo de Lete and Marcelo H. del Pilar.jpg|thumb|left|200px|Luna with fellow reformists Eduardo de Lete (center) and [[Marcelo H. del Pilar]] (right), Spain, 1890]] |

[[File:Antonio Luna, Eduardo de Lete and Marcelo H. del Pilar.jpg|thumb|left|200px|Luna with fellow reformists Eduardo de Lete (center) and [[Marcelo H. del Pilar]] (right), Spain, 1890]] |

||

In Spain, he became one of the Filipino [[expatriate]]s who mounted the [[Propaganda Movement]] and wrote for ''[[La Solidaridad]]'', headed by [[Galicano Apacible]]. He wrote a piece titled ''Impressions'' which dealt with Spanish customs and idiosyncrasies under the [[Pseudonym|pen-name]] "Taga-ilog". Also, like many of the Filipino liberals in Spain, Luna became a Freemason and rose to the degree of Master Mason.<ref name="Dumindin 2006" /> |

In Spain, he became one of the Filipino [[expatriate]]s who mounted the [[Propaganda Movement]] and wrote for ''[[La Solidaridad]]'', headed by [[Galicano Apacible]]. He wrote a piece titled ''Impressions'' which dealt with Spanish customs and idiosyncrasies under the [[Pseudonym|pen-name]] "Taga-ilog". Also, like many of the Filipino liberals in Spain, Luna became a Freemason and rose to the degree of Master Mason.<ref name="Dumindin 2006" /> |

||

He and his brother Juan also opened the ''Sala de Armas'', a fencing club, in [[Manila]].<ref name="Dumindin 2006"/> When he learned of the underground societies that were planning a revolution and was asked to join, he scoffed at the idea and turned down the offer. Like other Filipino [[émigrés]] involved in the Reform Movement, he was in favor of reform rather than revolution as the way toward independence.<ref name="PS 2008" /> Besides affecting their property, the proponents of the Reform Movement saw that no revolution would succeed without the necessary preparations.<ref name="Agoncillo 8th"/> Nevertheless, after the existence of the [[Katipunan]] was leaked in August 1896, the Luna brothers were arrested and jailed in [[Fort Santiago]] for "participating" in the revolution.<ref name="PS 2008" /> His statement concerning the revolution was one of the many statements used to abet the laying down of the death sentence for [[José Rizal]]. Months later, José and Juan were freed but Antonio was exiled to Spain in 1897, where he was imprisoned in Madrid's [[Cárcel Modelo (Madrid)|Cárcel Modelo]].<ref name="Dumindin 2006" /> |

He and his brother Juan also opened the ''Sala de Armas'', a fencing club, in [[Manila]].<ref name="Dumindin 2006"/> When he learned of the underground societies that were planning a revolution and was asked to join, he scoffed at the idea and turned down the offer. Like other Filipino [[émigrés]] involved in the Reform Movement, he was in favor of reform rather than revolution as the way toward independence.<ref name="PS 2008" /> Besides affecting their property, the proponents of the Reform Movement saw that no revolution would succeed without the necessary preparations.<ref name="Agoncillo 8th"/> Nevertheless, after the existence of the [[Katipunan]] was leaked in August 1896, the Luna brothers were arrested and jailed in [[Fort Santiago]] for "participating" in the revolution.<ref name="PS 2008" /> His statement concerning the revolution was one of the many statements used to abet the laying down of the death sentence for [[José Rizal]]. Months later, José and Juan were freed but Antonio was exiled to Spain in 1897, where he was imprisoned in Madrid's [[Cárcel Modelo (Madrid)|Cárcel Modelo]].<ref name="Dumindin 2006" /> |

||

His more famous and controversial brother, Juan, who had been pardoned by the Spanish Queen Regent [[Maria Christina of Austria]] herself, left for Spain to use his influence to intercede for Antonio in August 1897. Antonio's case was dismissed by the Military Supreme Court and he was released.<ref name="PS 2008" /><ref name="historybehindmovie14" /> Upon his release in December 1897, Luna studied field fortifications, [[guerrilla warfare]], organization, and other aspects of military science under [[Gerard Leman]], who would later be the commanding general of the fortress at [[Liège]].<ref name="Dumindin 2006" /> He also read extensively about the discipline when he was at the [[Ateneo de Madrid]].<ref name="historybehindmovie14" /> The second phase of the revolution began with the return of [[Emilio Aguinaldo |

His more famous and controversial brother, Juan, who had been pardoned by the Spanish Queen Regent [[Maria Christina of Austria]] herself, left for Spain to use his influence to intercede for Antonio in August 1897. Antonio's case was dismissed by the Military Supreme Court and he was released.<ref name="PS 2008" /><ref name="historybehindmovie14" /> Upon his release in December 1897, Luna studied field fortifications, [[guerrilla warfare]], organization, and other aspects of military science under [[Gerard Leman]], who would later be the commanding general of the fortress at [[Liège]].<ref name="Dumindin 2006" /> He also read extensively about the discipline when he was at the [[Ateneo de Madrid]].<ref name="historybehindmovie14" /> The second phase of the revolution began with the return of [[Emilio Aguinaldo]] by the US Navy to [[Cavite]] in 1898 his establishment of the [[Dictatorial Government of the Philippines]].<ref name="Agoncillo 8th" /><ref name="intro" /> Upon arriving in Hong Kong, Luna was given a letter of recommendation to Aguinaldo and a [[revolver]] by [[Felipe Agoncillo]] and he returned to the Philippines in July 1898.<ref name="Jose1972p58" /> |

||

== |

==Personal life== |

||

Luna courted Nellie Boustead, a woman who was also courted by [[José Rizal]], between 1889 and 1891.<ref name="PS 2008" /> Boustead was reportedly infatuated with Rizal. At a party held by Filipinos, a drunk Antonio Luna made unsavory remarks against Boustead. This prompted Rizal to challenge Luna to a duel. However, Luna apologized to Rizal, thus averting a duel between the compatriots.<ref name="A.R. Ocampo 2010" /> |

Luna courted Nellie Boustead, a woman who was also courted by [[José Rizal]], between 1889 and 1891.<ref name="PS 2008" /> Boustead was reportedly infatuated with Rizal. At a party held by Filipinos, a drunk Antonio Luna made unsavory remarks against Boustead. This prompted Rizal to challenge Luna to a duel. However, Luna apologized to Rizal, thus averting a duel between the compatriots.<ref name="A.R. Ocampo 2010" /> |

||

== |

==Philippine–American War== |

||

=== |

===Prior to the war=== |

||

Since June 1898, Manila had been surrounded by the revolutionary troops. Colonel Luciano San Miguel occupied Mandaluyong, General [[Pío del Pilar]], [[Makati]], General [[Mariano Noriel]], [[Parañaque]], Colonel Enrique Pacheco, [[Navotas]], Tambobong and [[Caloocan]]. General [[Gregorio del Pilar]] marched through [[Sampaloc, Manila|Sampaloc]], taking [[Tondo, Manila|Tondo]], [[Divisoria]], and Azcárraga, Noriel cleared Singalong and [[Paco, Manila|Paco]], and held [[Ermita]] and [[Malate, Manila|Malate]].<ref name="Manila" /> Luna thought the Filipinos should enter [[Intramuros]] to have joint occupation of the walled city. But Aguinaldo, heeding the advice of General [[Wesley Merritt]] and Commodore (later Admiral) [[George Dewey]], whose fleet had moored in [[Manila Bay]], sent Luna to the [[trench]]es where he ordered his troops to fire on the Americans. After the chaos following the American occupation, at a meeting in Ermita, Luna tried to complain to American officers about the disorderly conduct of their soldiers.<ref name="PS 2008" /> |

|||

Since June 1898, Manila had been surrounded by the revolutionary troops. Colonel Luciano San Miguel occupied Mandaluyong, General [[Pío del Pilar]] advanced through Sampaloc and attacked [[Puente Colgante (Manila)|Puente Colgante]], causing the enemy to fall back, General [[Mariano Noriel]], [[Parañaque]], Colonel Enrique Pacheco, [[Navotas]], Tambobong and [[Caloocan]]. General [[Gregorio del Pilar]] took charge of Pantaleon Garcia's force when the latter was wounded, taking Pritil, [[Tondo, Manila|Tondo]], [[Divisoria]], and Paseo de Azcárraga, Noriel cleared Singalong and [[Paco, Manila|Paco]], and held [[Ermita]] and [[Malate, Manila|Malate]].<ref name="Manila" /><ref name="True Version of the Philippine Revolution">{{Citation|last=Aguinaldo|first=Don Emilio y Famy|author-link=Emilio Aguinaldo|url=https://www.gutenberg.org/files/12996/12996-h/12996-h.htm|title=True Version of the Philippine Revolution|publisher=Project Gutenberg|access-date=November 20, 2023|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230708225540/https://www.gutenberg.org/files/12996/12996-h/12996-h.htm|archive-date=July 8, 2023}} |

|||

</ref> Aguinaldo demanded joint occupation of [[Intramuros]], which the Americans heeded. After one month of joint occupation, Aguinaldo withdrew his forces when he received a telegram from General Elwell Otis that he would be obliged to resort to forcible action if Aguinaldo did not pull his forces back, and Commodore (later Admiral) [[George Dewey]]'s fleet had moored in [[Manila Bay]] after being warned of an unwanted conflict between Filipinos and Americans. When Luna was in the [[trench]]es, he ordered his troops to fire on the Americans. After the chaos following the American occupation, at a meeting in Ermita, Luna tried to complain to American officers about the disorderly conduct of their soldiers.<ref name="PS 2008" /> |

|||

To silence Luna, Aguinaldo appointed him as Chief of War Operations on September 26, 1898, and assigned the rank of [[brigadier general]]. In quick succession, he was made the Director or Assistant Secretary of War and Supreme Chief of the [[Philippine Revolutionary Army|Republican Army]] on September 28,<ref name="VddRY"/> arousing the envy of the other generals who were fighting since the first phase of the [[Philippine Revolution|Revolution]]. Meanwhile, Luna felt that bureaucratic placebos were being thrown his way when all he wanted was to organize and discipline the enthusiastic but ill-fed and ill-trained troops into a real army.<ref name="PS 2008" /> |

To silence Luna, Aguinaldo appointed him as Chief of War Operations on September 26, 1898, and assigned the rank of [[brigadier general]]. In quick succession, he was made the Director or Assistant Secretary of War and Supreme Chief of the [[Philippine Revolutionary Army|Republican Army]] on September 28,<ref name="VddRY"/> arousing the envy of the other generals who were fighting since the first phase of the [[Philippine Revolution|Revolution]]. Meanwhile, Luna felt that bureaucratic placebos were being thrown his way when all he wanted was to organize and discipline the enthusiastic but ill-fed and ill-trained troops into a real army.<ref name="PS 2008" /> |

||

| Line 91: | Line 102: | ||

On September 15, 1898, the Malolos Congress, the [[constituent assembly]] of the [[First Philippine Republic]], was convened in [[Barasoain Church]].<ref name="kalaw1927pp120,124-125" /> Luna would be one of the elected representatives and was narrowly defeated by [[Pedro Paterno]] as President of the Congress with a vote of 24–23.<ref name="Jose1972p450" /> |

On September 15, 1898, the Malolos Congress, the [[constituent assembly]] of the [[First Philippine Republic]], was convened in [[Barasoain Church]].<ref name="kalaw1927pp120,124-125" /> Luna would be one of the elected representatives and was narrowly defeated by [[Pedro Paterno]] as President of the Congress with a vote of 24–23.<ref name="Jose1972p450" /> |

||

Seeing the need for a military school, in October 1898, Luna established a military academy at [[Malolos]], known as the ''Academia Militar'' |

Seeing the need for a military school, in October 1898, Luna established a military academy at [[Malolos]], known as the ''Academia Militar''. He appointed Colonel Manuel Bernal Sityar, a [[mestizo]] who was formerly a lieutenant serving the [[Civil Guard (Philippines)|Civil Guard]], as superintendent. He recruited other mestizos and Spaniards who had fought in the Spanish Army during the [[Philippine Revolution|1896 Revolution]] for training. However, the academy had to be suspended indefinitely by March 1899 due to the outbreak of the Philippine–American War.<ref name="PS 2008" /> |

||

[[File:La Independencia staff.jpg|thumb|Luna (center row, seated left) and the staff of ''La Independencia'' in 1898]] |

[[File:La Independencia staff.jpg|thumb|Luna (center row, seated left) and the staff of ''La Independencia'' in 1898]] |

||

[[File: General Manuel Tinio, General Benito Natividad, LtCol Jose Alejandrino.jpg|thumb|Group showing some of Luna's aides: General [[Manuel Tinio]] (seated, center), General [[Benito Natividad]] (seated, 2nd from right), General [[Jose Alejandrino]] (seated, 2nd from left)]] |

[[File: General Manuel Tinio, General Benito Natividad, LtCol Jose Alejandrino.jpg|thumb|Group showing some of Luna's aides: General [[Manuel Tinio]] (seated, center), General [[Benito Natividad]] (seated, 2nd from right), General [[Jose Alejandrino]] (seated, 2nd from left)]] |

||

A score of veteran officers became teachers at his military school. Luna devised two courses of instruction, planned the reorganization, with a [[battalion]] of ''tiradores'' and a [[squadron (army)|cavalry squadron]], set up an inventory of guns and ammunition, arsenals, using convents and town halls, [[quartermaster]]s, [[lookout]]s and communication systems. He built trenches with the help of his chief engineer, General [[Jose Alejandrino]], and had his brother [[Juan Luna|Juan]] design the school's uniforms (the Filipino [[rayadillo]]). He also insisted on strict discipline over and above clan armies and regional loyalties, which prevented coordination between various military units.<ref name="Jose1972p206" /> Envisioning one united army for the Republic, clan armies |

A score of veteran officers became teachers at his military school. Luna devised two courses of instruction, planned the reorganization, with a [[battalion]] of ''tiradores'' and a [[squadron (army)|cavalry squadron]], set up an inventory of guns and ammunition, arsenals, using convents and town halls, [[quartermaster]]s, [[lookout]]s and communication systems. He built trenches with the help of his chief engineer, General [[Jose Alejandrino]], and had his brother [[Juan Luna|Juan]] design the school's uniforms (the Filipino [[rayadillo]]). He also insisted on strict discipline over and above clan armies and regional loyalties, which prevented coordination between various military units.<ref name="Jose1972p206" /> Envisioning one united army for the Republic, clan armies and regional loyalties presented a lack of national consciousness.<ref name="Evqk6" /> |

||

Convinced that the fate of the infant Republic should be a contest for the minds of Filipinos, Luna turned to journalism to strengthen Filipino minds with the ideas of nationhood and the need to fight the Americans. He decided to publish a newspaper, ''La Independencia''.<ref name="Sonnichsen" />{{rp|63}} This four-page daily was filled with articles, short stories, patriotic songs and poems. The staff was installed in one of the coaches of the train that ran from Manila to [[Pangasinan]]. The paper came out in September 1898 and was an instant success. A movable feast of information, humor, and good writing, 4,000 copies were printed, which was more than all the other newspapers in circulation put together.<ref name="Jose1972p269" /> |

Convinced that the fate of the infant Republic should be a contest for the minds of Filipinos, Luna turned to journalism to strengthen Filipino minds with the ideas of nationhood and the need to fight the Americans. He decided to publish a newspaper, ''La Independencia''.<ref name="Sonnichsen" />{{rp|63}} This four-page daily was filled with articles, short stories, patriotic songs and poems. The staff was installed in one of the coaches of the train that ran from Manila to [[Pangasinan]]. The paper came out in September 1898 and was an instant success. A movable feast of information, humor, and good writing, 4,000 copies were printed, which was more than all the other newspapers in circulation put together.<ref name="Jose1972p269" /> |

||

When the [[Treaty of Paris (1898)|Treaty of Paris]], under which Spain was to cede the Philippines to the United States, was made public in December 1898, Luna quickly decided to take military action. He proposed a strategy that was designed to trap the Americans in Manila before more of their troops could land by executing surprise attacks ([[guerrilla warfare]]) while building up strength in the north. If the American forces penetrated his lines, Luna determined that he would wage a series of delaying battles and prepare a [[fortress]] in northern [[Luzon]], |

When the [[Treaty of Paris (1898)|Treaty of Paris]], under which Spain was to cede the Philippines to the United States, was made public in December 1898, Luna quickly decided to take military action. He proposed a strategy that was designed to trap the Americans in Manila before more of their troops could land by executing surprise attacks ([[guerrilla warfare]]) while building up strength in the north. If the American forces penetrated his lines, Luna determined that he would wage a series of delaying battles and prepare a [[fortress]] in northern [[Luzon]], the [[Cordillera Central, Luzon|Cordillera]]. This, however, was turned down by high command, which still believed that the Americans would grant full independence.<ref name="Jose1972p172" /> |

||

=== |

===Outbreak of the war=== |

||

[[File: Manila646 1899.jpg|thumb|right|American soldiers of the 1st Nebraska Volunteers, Company B, during the [[Battle of Manila (1899)|Battle of Manila]]]] |

[[File: Manila646 1899.jpg|thumb|right|American soldiers of the 1st Nebraska Volunteers, Company B, during the [[Battle of Manila (1899)|Battle of Manila]]]] |

||

| ⚫ |

The Americans gained |

||

| ⚫ | The Americans gained the opportunity to start hostilities with the Filipinos at the place and time of their choice. On the night of February 4, 1899, when most of the Filipino generals were at a ball in Malolos to celebrate the success of the [[American Anti-Imperialist League|American anti-imperialists]] delaying the ratification of the Treaty of Paris, the Americans staged an incident along the concrete blockhouses in [[Santa Mesa]] near the Balsahan Bridge.<ref name="Malolos crisis" /> An American patrol fired on Filipino troops, claiming afterward that the Filipinos had started shooting first. The whole Filipino line from [[Pasay]] to Caloocan returned fire and [[Battle of Manila (1899)|the first battle of the Filipino-American War]] ensued. Two days later, in response to the incident, the US Senate voted for [[annexation]]. In doing so, the conflict became the war of conquest, occupation, and annexation that Luna, [[Apolinario Mabini|Mabini]], and others had predicted and about which they had warned Aguinaldo and his generals previously.<ref name="Jose1972p178" /> |

||

| ⚫ |

Luna, after receiving orders from Aguinaldo, rushed to the front lines from his headquarters at Polo (present-day [[Valenzuela, Philippines|Valenzuela City]]) and led three companies to La Loma to engage General [[Arthur MacArthur, Jr.|Arthur MacArthur]]'s forces. Fighting took place at [[Marikina]], [[Caloocan]], [[Santa Ana, Manila|Santa Ana]], and [[Paco, Manila|Paco]]. The Filipinos were subjected to a carefully planned attack with [[naval artillery]], with Admiral [[George Dewey]]'s US fleet firing from [[Manila Bay]]. Filipino casualties were high, amounting to around 2,000 killed and wounded.<ref name="Malolos crisis" /> Luna personally had to carry wounded officers and men to safety; of these, the most dramatic rescue was that of Commander [[José Torres Bugallón]]. After being hit by an American bullet, Bugallón had managed to advance another fifty meters before he was seen by Luna collapsing by the side of the road. As the Americans continued their fire on the road, Luna gathered an escort of around 25 men to save Bugallón, who Luna stated was equivalent to 500 men. Surviving the encounter, Luna encouraged Bugallón to live by giving |

||

| ⚫ | Luna, after receiving orders from Aguinaldo, rushed to the front lines from his headquarters at Polo (present-day [[Valenzuela, Philippines|Valenzuela City]]) and led three companies to La Loma to engage General [[Arthur MacArthur, Jr.|Arthur MacArthur]]'s forces. Fighting took place at [[Marikina]], [[Caloocan]], [[Santa Ana, Manila|Santa Ana]], and [[Paco, Manila|Paco]]. The Filipinos were subjected to a carefully planned attack with [[naval artillery]], with Admiral [[George Dewey]]'s US fleet firing from [[Manila Bay]]. Filipino casualties were high, amounting to around 2,000 killed and wounded.<ref name="Malolos crisis" /> Luna personally had to carry wounded officers and men to safety; of these, the most dramatic rescue was that of Commander [[José Torres Bugallón]]. After being hit by an American bullet, Bugallón had managed to advance another fifty meters before he was seen by Luna collapsing by the side of the road. As the Americans continued their fire on the road, Luna gathered an escort of around 25 men to save Bugallón, who Luna stated was equivalent to 500 men. Surviving the encounter, Luna encouraged Bugallón to live by giving him an instant promotion to lieutenant colonel. However, Bugallón succumbed to his wounds.<ref name="Jose1972p186" /> |

||

On February 7, Luna issued a detailed order to the field officers of the territorial militia. Containing five specific objects, it began with "Under the barbarous attack upon our army on February 4", and ended with "...war without quarter to false Americans who wish to enslave us. Independence or death!" The order labeled the US forces "an army of drunkards and thieves"<ref name="Malolos crisis" /> in response to the continued bombardment of the towns around Manila, the burning and looting of whole districts, and the raping of Filipino women by US troops.<ref name="Jose1972p2300" /> |

On February 7, Luna issued a detailed order to the field officers of the territorial militia. Containing five specific objects, it began with "Under the barbarous attack upon our army on February 4", and ended with "...war without quarter to false Americans who wish to enslave us. Independence or death!" The order labeled the US forces "an army of drunkards and thieves"<ref name="Malolos crisis" /> in response to the continued bombardment of the towns around Manila, the burning and looting of whole districts, and the raping of Filipino women by US troops.<ref name="Jose1972p2300" /> |

||

| Line 111: | Line 123: | ||

When Luna saw that the American advance had halted, mainly to stabilize their lines, he again mobilized his troops to attack [[Quezon City#La Loma|La Loma]] on February 10. Fierce fighting ensued but the Filipinos were forced to withdraw thereafter.<ref name="Jose1972p210" /> Caloocan has left with American forces in control of the southern terminus of the Manila to [[Dagupan]] railway, along with five engines, fifty [[passenger coach]]es, and a hundred [[freight car]]s. After consolidating control of Caloocan, the obvious next objective for American forces would be the Republic capital at Malolos. However, General [[Elwell Stephen Otis|Elwell Otis]] delayed for almost a month in hopes that Filipino forces would be deployed in its defense.<ref name="Linn2000p92" /> |

When Luna saw that the American advance had halted, mainly to stabilize their lines, he again mobilized his troops to attack [[Quezon City#La Loma|La Loma]] on February 10. Fierce fighting ensued but the Filipinos were forced to withdraw thereafter.<ref name="Jose1972p210" /> Caloocan has left with American forces in control of the southern terminus of the Manila to [[Dagupan]] railway, along with five engines, fifty [[passenger coach]]es, and a hundred [[freight car]]s. After consolidating control of Caloocan, the obvious next objective for American forces would be the Republic capital at Malolos. However, General [[Elwell Stephen Otis|Elwell Otis]] delayed for almost a month in hopes that Filipino forces would be deployed in its defense.<ref name="Linn2000p92" /> |

||

|

With their superior firepower and newly arrived reinforcements, the Americans had not expected such resistance. They were so surprised that an urgent cable was sent to General [[Henry Ware Lawton|Henry Lawton]] who was in Colombo, Ceylon (now [[Sri Lanka]]), with his troops. The [[Telegraphy#Telegraph services|telegram]] stated, "Situation critical in Manila. Your early arrival great importance."<ref name="Jose1972p13" /> |

||

=== |

===Luna Sharpshooters and the Black Guard=== |

||

{{ |

{{Main|Luna Sharpshooters}} |

||

| ⚫ |

The [[Luna Sharpshooters]] was a short-lived unit formed by Luna to serve under the [[Philippine Revolutionary Army]]. On February 11, eight [[infantrymen]], formerly under Captains Márquez and Jaro, were sent by then-Secretary of War [[Baldomero Aguinaldo]] to Luna, then-Assistant Secretary of War. The infantrymen were disarmed by the Americans |

||

| ⚫ | The [[Luna Sharpshooters]] was a short-lived unit formed by Luna to serve under the [[Philippine Revolutionary Army]]. On February 11, eight [[infantrymen]], formerly under Captains Márquez and Jaro, were sent by then-Secretary of War [[Baldomero Aguinaldo]] to Luna, then-Assistant Secretary of War. The infantrymen were disarmed by the Americans, and journeyed to be [[Commission (document)|commissioned]] in the regular Filipino army. Seeing their desire to serve in the army, Luna took them in and from there the group grew and emerged as the Luna Sharpshooters.<ref name="Jose1972p220"/> The sharpshooters became famous for their fierce fighting and proved their worth by spearheading every major battle in the [[Philippine–American War]]. After the [[Battle of Calumpit]] on April 25–27, 1899, only seven or eight remained in the regular Filipino army.<ref name="Jose1972p220" /> In the [[Battle of Paye]] on December 18, 1899, a Filipino [[sharpshooter]], Private Bonifacio Mariano, under the command of General [[Licerio Gerónimo]] killed General [[Henry Ware Lawton]], making the latter the highest-ranking casualty during the course of the war.<ref name="a37Cd" /> |

||

| ⚫ |

Luna also formed other units similar to the sharpshooters. One was the unit, which would later be named after Bugallón |

||

| ⚫ | Luna also formed other units similar to the sharpshooters. One was the unit commanded by Rosendo Simón de Pajarillo, which would later be named after Bugallón. The unit emerged from a group of ten men wanting to volunteer in the regular Filipino army. Luna, still thinking of the defeat at the [[Battle of Caloocan]], sent the men away at first. However, he soon changed his mind and decided to give the men an initiation.<ref name="Jose1972p220" /> After taking breakfast, he ordered a subordinate, Colonel Queri, to prepare arms and ammunition for the ten men. Then, the men boarded a train destined towards Malinta, which was American-held territory. After giving orders to the men, he let them go and watched them with his telescope. The men succeeded in their mission and eventually returned unharmed. Admiring their bravery, he organized them into a guerrilla unit of around 50 members. This unit would see action in the [[Second Battle of Caloocan]].<ref name="Jose1972p220" /> |

||

| ⚫ |

Another elite unit was the Black Guard, a 25-man guerrilla unit under a certain Lieutenant García. García, one of Luna's favorites, was a modest but brave soldier. His unit was tasked to approach the enemy by surprise and quickly return to camp. Luna had admired García's unit |

||

| ⚫ | Another elite unit was the Black Guard, a 25-man guerrilla unit under a certain Lieutenant García. García, one of Luna's favorites, was a modest but brave soldier. His unit was tasked to approach the enemy by surprise and quickly return to camp. Luna had admired García's unit so much that he wanted to increase their size. However, García declined the offer, believing that a larger force might undermine the efficiency of their work.<ref name="Jose1972p220" /> [[Jose Alejandrino]], the chief army engineer and one of Luna's aides, stated that he never heard of García and his unit again after Luna's resignation on February 28.<ref name="la senda" /> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

[[File:Tomas Mascardo.jpg|thumb|right|General [[Tomás Mascardo]], military commander of Pampanga]] |

[[File:Tomas Mascardo.jpg|thumb|right|General [[Tomás Mascardo]], military commander of Pampanga]] |

||

A [[Second Battle of Caloocan|Filipino counterattack]] began at dawn on February 23. The plan was to employ a [[pincer movement]], using the battalions from the North and South, with the sharpshooters (the only professionally trained troops) at crucial points. The |

A [[Second Battle of Caloocan|Filipino counterattack]] began at dawn on February 23. The plan was to employ a [[pincer movement]], using the battalions from the North and South, with the sharpshooters (the only professionally trained troops) at crucial points. The [[sandatahan|sandatahanes]]or''bolomen'' inside Manila would start a great fire to signal the start of the assault.<ref name="Jose1972p225" /> Troops directly under Luna's command were divided into three: the West Brigade under General Pantaleon García, the Center Brigade under General [[Mariano Llanera]], and the East Brigade under General [[Licerio Gerónimo]].<ref name="Jose1972p229" /> Luna also requested the battle-hardened [[Tinio Brigade]] from [[Northern Luzon]], under the command of General [[Manuel Tinio]]. It had more than 1,900 soldiers. However, Aguinaldo gave only ambiguous answers and the Tinio Brigade was unable to participate in the battle.<ref name="Jose1972p229" /> The battle was only partly successful because of two main reasons. Firstly, some of the successful Filipino sectors ran low on ammunition and food and were thus forced to withdraw to Polo. Secondly, Luna failed to relieve the [[Pampanga Battalion|Kapampangan militia]], already past their prime, when the battalion from [[Kawit]], [[Cavite]], refused to replace the former, saying that they had orders to obey only instructions directly from Aguinaldo. Such [[insubordination]] had become quite common among the Filipino forces at that time as most of the troops owed their loyalty to the officers from their provinces, towns, or districts and not to the central command. As a result, the counterattack soon collapsed, and Luna placated himself by personally disarming the Kawit Battalion.<ref name="Jose1972p241" /> |

||

[[File:1st Nebraskan Volunteers advancing on Santo Tomas.jpg|thumb|right|1st Nebraskan Volunteers advancing during the [[Battle of Santo Tomas]]]] |

[[File:1st Nebraskan Volunteers advancing on Santo Tomas.jpg|thumb|right|1st Nebraskan Volunteers advancing during the [[Battle of Santo Tomas]]]] |

||

Luna, however, proved to be a strict disciplinarian and his temper alienated many in the ranks of the common soldiers. An example of this occurred during the [[Battle of Calumpit]], wherein Luna ordered General [[Tomás Mascardo]] to send troops from [[Guagua, Pampanga|Guagua]] to strengthen the former's defenses. However, Mascardo ignored orders by Luna insisting that he was going to [[Arayat, Pampanga|Arayat]] to undertake an "inspection of troops". Another version of Mascardo's reasoning emerged and |

Luna, however, proved to be a strict disciplinarian and his temper alienated many in the ranks of the common soldiers. An example of this occurred during the [[Battle of Calumpit]], wherein Luna ordered General [[Tomás Mascardo]] to send troops from [[Guagua, Pampanga|Guagua]] to strengthen the former's defenses. However, Mascardo ignored orders by Luna insisting that he was going to [[Arayat, Pampanga|Arayat]] to undertake an "inspection of troops". Another version of Mascardo's reasoning emerged and claimed that Mascardo had left to visit his girlfriend, which was probably the version which reached Luna. Luna, infuriated by Mascardo's actions, decided to detain him. Major Hernando, one of Luna's aides, tried to placate the general's anger and convinced Luna to push the case to President Aguinaldo. Aguinaldo complied and detained Mascardo for 24 hours. Upon returning to the field, however, the Americans had broken through his defenses at the Bagbag River, forcing Luna to withdraw despite his heroic efforts to defend the remaining sectors.<ref name="Dumindin 2006" /> |

||

Luna resigned on March 1, mainly |

Luna resigned on March 1, mainly resenting the rearmament of the Kawit Battalion as the Presidential Guard.<ref name="historybehindmovie16" /> Aguinaldo hesitantly accepted the resignation. As a result, Luna was absent from the field for three weeks, during which the Filipino forces suffered several defeats and setbacks. One such defeat would be at the [[Battle of Marilao River]] on March 27.<ref name="Dumindin Malolos" /> Receiving the depressing reports from the field through his ''La Independencia'' correspondents, Luna went to Aguinaldo and asked to be reinstated with more powers over all the military heads, and Aguinaldo promoted him to [[Lieutenant General]] and agreed to make him Commander-in-Chief of all the Filipino forces in Central Luzon ([[Bulacan]], [[Tarlac]], [[Pampanga]], [[Nueva Ecija]], [[Bataan]], and [[Zambales]]).<ref name="Jose1972p269" /><ref name="Jose1972p293" /> |

||

The Luna Defense Line was planned to create a series of delaying battles from [[Caloocan]] to [[Angeles, Pampanga]],<ref name="FM"/>{{page needed|date=September 2022}} as the Republic was constructing a guerrilla base in the [[Mountain Province]]. The base was planned to be the last stand headquarters of the Republic in case the Americans broke through the Defense Line.<ref name="Jose1972p280"/> American military observers were astonished by the Defense Line, which they described as consisting of numerous bamboo trenches stretching from town to town. The series of trenches allowed the Filipinos to withdraw gradually, firing from cover at the advancing Americans. As the American troops occupied each new position, they were subjected to a series of traps that had been set in the trenches, |

The Luna Defense Line was planned to create a series of delaying battles from [[Caloocan]] to [[Angeles, Pampanga]],<ref name="FM"/>{{page needed|date=September 2022}} as the Republic was constructing a guerrilla base in the [[Mountain Province]]. The base was planned to be the last stand headquarters of the Republic in case the Americans broke through the Defense Line.<ref name="Jose1972p280"/> American military observers were astonished by the Defense Line, which they described as consisting of numerous bamboo trenches stretching from town to town. The series of trenches allowed the Filipinos to withdraw gradually, firing from cover at the advancing Americans. As the American troops occupied each new position, they were subjected to a series of traps that had been set in the trenches, including bamboo spikes and poisonous reptiles.<ref name="Jose1972p318" /> |

||

Earlier in May 1899, Luna almost fell in the field at the [[Battle of Santo Tomas]]. Mounted on his horse, Luna |

Earlier in May 1899, Luna almost fell in the field at the [[Battle of Santo Tomas]]. Mounted on his horse, Luna charged into the battlefield leading his main force in a counterattack. As they advanced, the American forces began firing upon them. Luna's horse was hit and he fell to the ground. As he recovered, Luna realized that he had been shot in the stomach, and he attempted to kill himself with his revolver to avoid capture.<ref name="Jose1972p314"/> He was saved, though, by the actions of a Filipino colonel named Alejandro Avecilla who, seeing Luna fall, rode towards the general to save him. Despite being heavily wounded in one of his legs and an arm, with his remaining strength Avecilla carried Luna away from the battle to the Filipino rear. Upon reaching safety, Luna realized that his wound was not very deep as most of the bullet's impact had been taken by a silk belt full of gold coins that his parents had given him.<ref name="Jose1972p314"/> As he left the field to have his wounds tended, Luna turned over the command to General [[Venacio Concepción]], the Filipino commander of the nearby town of Angeles.<ref name="Dumindin 2006"/> In recognition of his work, Luna was awarded the Philippine Republic Medal.<ref name="Jose1972p314"/> By the end of May 1899, Colonel Joaquín Luna, one of Antonio's brothers, warned him that a plot had been concocted by "old elements" or the autonomists of the Republic (who were bent on accepting American sovereignty over the country) and a clique of army officers whom Luna had disarmed, arrested, and/or insulted. Luna shrugged off all these threats, reiterating his trust for Aguinaldo, and continued building defenses at Pangasinan where the Americans were planning a landing.<ref name="Jose1972p372" /> |

||

==Assassination and aftermath== |

==Assassination and aftermath== |

||

[[File:Francisco "Paco" Roman, c. 1899.jpg|thumb|right|Colonel [[Paco Román|Francisco Román]], Luna's aide-de-camp, was assassinated with him.]] |

[[File:Francisco "Paco" Roman, c. 1899.jpg|thumb|right|Colonel [[Paco Román|Francisco Román]], Luna's aide-de-camp, was assassinated with him.]] |

||

| ⚫ |

On June 2, 1899, Luna received two telegrams (initially four, but he never received the last two) – one asked for help in launching a counterattack in [[San Fernando, Pampanga]]; and the other, sent by Aguinaldo himself,<ref name="nolisoli.ph" /> ordered him to go to the new capital at [[Cabanatuan]], [[Nueva Ecija]] to form a new [[Cabinet (government)|cabinet]].<ref name="Jose1972p377" /> In his jubilation, Luna wrote [[Arcadio Maxilom]], military commander of [[Cebu]], to stand firm in the war.<ref name="Jose1972p377" /> Luna set off from [[Bayambang]], first by train, then on horseback, and eventually in three carriages to Nueva Ecija with 25 of his men.<ref name="Dumindin 2006" /><ref name="Malolos crisis" /> During the journey, two of the carriages broke down, so he proceeded with just one carriage with [[Paco Roman|Colonel Francisco Román]] and Captain Eduardo Rusca, having earlier shed his cavalry escort.{{citation needed|date=July 2019}} On June 4, Luna sent a telegram to Aguinaldo confirming his arrival. Upon arriving at Cabanatuan on June 5, Luna proceeded to the headquarters, |

||

| ⚫ | On June 2, 1899, Luna received two telegrams (initially four, but he never received the last two) – one asked for help in launching a counterattack in [[San Fernando, Pampanga]]; and the other, sent by Aguinaldo himself,<ref name="nolisoli.ph" /> ordered him to go to the new capital at [[Cabanatuan]], [[Nueva Ecija]] to form a new [[Cabinet (government)|cabinet]].<ref name="Jose1972p377" /> In his jubilation, Luna wrote [[Arcadio Maxilom]], military commander of [[Cebu]], to stand firm in the war.<ref name="Jose1972p377" /> Luna set off from [[Bayambang]], first by train, then on horseback, and eventually in three carriages to Nueva Ecija with 25 of his men.<ref name="Dumindin 2006" /><ref name="Malolos crisis" /> During the journey, two of the carriages broke down, so he proceeded with just one carriage with [[Paco Roman|Colonel Francisco Román]] and Captain Eduardo Rusca, having earlier shed his cavalry escort.{{citation needed|date=July 2019}} On June 4, Luna sent a telegram to Aguinaldo confirming his arrival. Upon arriving at Cabanatuan on June 5, Luna proceeded aloneto the [[Cabanatuan Cathedral|church in Cabanatuan]], where the headquarters was located,<ref name="PlazaLucero">{{Cite news |last=Galang |first=Armand |date=June 11, 2019 |title=In Nueva Ecija, Antonio Luna remembered sans fanfare |url=https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1128788/in-nueva-ecija-antonio-luna-remembered-sans-fanfare |access-date=January 29, 2024 |work=[[The Philippine Star]]}}</ref> to communicate with the President. As he went up the stairs, he ran into an officer whom he had previously disarmed for insubordination: Captain Pedro Janolino, commander of the Kawit Battalion, and an old enemy whom he had once threatened with arrest for favoring American autonomy. Captain Janolino was accompanied by [[Felipe Buencamino]], the [[Secretary of Foreign Affairs (Philippines)|Minister of Foreign Affairs]], and a member of the Cabinet. He was told that Aguinaldo had left for [[San Isidro, Nueva Ecija|San Isidro]] in [[Nueva Ecija]] (he actually went to [[Bamban, Tarlac]]). Enraged, Luna asked why he had not been told that the meeting was canceled.<ref name="Jose1972p429" /> |

||

| ⚫ |

Both exchanged heated words as he was about to depart. |

||

| ⚫ | Both exchanged heated words as he was about to depart. At [[Plaza Lucero]], fronting the [[Cabanatuan Cathedral|church of Cabanatuan]],<ref name="inqluna">{{cite news |title=In Nueva Ecija, Antonio Luna remembered sans fanfare |url=https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1128788/in-nueva-ecija-antonio-luna-remembered-sans-fanfare |access-date=June 26, 2021 |newspaper=Philippine Daily Inquirer |date=June 11, 2019 |archive-date=June 26, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210626125530/https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1128788/in-nueva-ecija-antonio-luna-remembered-sans-fanfare |url-status=live }}</ref> a rifle shot rang out. Still outraged and furious, Luna rushed down the stairs and met Janolino, accompanied by some elements of the Kawit Battalion. Janolino swung his [[Bolo knife|bolo]] at Luna, wounding him in the head. Janolino's men fired at Luna, while others started stabbing him, even as he tried to fire his revolver at one of his attackers.<ref name="Jose1972p429" /> He staggered out into the plaza where Román and Rusca were rushing to his aid, but as he lay dying, they too were set upon and shot, with Román being killed and Rusca being severely wounded. Luna received more than 30 wounds,<ref name="Jose1972p436" /> and uttered "Cowards! Assassins!"<ref name="Jose1972p429" /> He was hurriedly buried in the [[churchyard]], after which Aguinaldo [[Relief (military)|relieved]] Luna's officers and men from the field, including General [[Venacio Concepción]], whose headquarters in [[Angeles, Pampanga]] was besieged by Aguinaldo on the same day Luna was assassinated. |

||

Immediately after Luna's death, confusion reigned on both sides. The Americans even thought Luna had taken over to replace Aguinaldo.<ref name="Jose1972p375" /> Luna's death was publicly declared only by June 8, and a circular providing details of the event released by June 13. While investigations were supposedly made concerning Luna's death, not one person was [[convicted]].<ref name="Jose1972p388" /> Later, General Pantaleon García said that it was he who was verbally ordered by Aguinaldo to conduct the assassination of Luna at Cabanatuan. His sickness at the time prevented his participation in the assassination.<ref name="Pantaleon Garcia">{{cite web|url=https://www.filipinaslibrary.org.ph/biblio/106315/|title=Declaration of Pantaleon Garcia, 5 June 1921, stating Aguinaldo gave him verbal orders to assassinate Antonio Luna but he was ill and couldn't comply|date=June 5, 1921|publisher=[[Ayala Museum|Filipinas Heritage Library]]}}</ref> Aguinaldo would be firm in his stand that he had nothing to do with the assassination of Luna.<ref name="MjLoO" /> |

Immediately after Luna's death, confusion reigned on both sides. The Americans even thought Luna had taken over to replace Aguinaldo.<ref name="Jose1972p375" /> Luna's death was publicly declared only by June 8, and a circular providing details of the event released by June 13. While investigations were supposedly made concerning Luna's death, not one person was [[convicted]].<ref name="Jose1972p388" /> Later, General Pantaleon García said that it was he who was verbally ordered by Aguinaldo to conduct the assassination of Luna at Cabanatuan. His sickness at the time prevented his participation in the assassination.<ref name="Pantaleon Garcia">{{cite web|url=https://www.filipinaslibrary.org.ph/biblio/106315/|title=Declaration of Pantaleon Garcia, 5 June 1921, stating Aguinaldo gave him verbal orders to assassinate Antonio Luna but he was ill and couldn't comply|date=June 5, 1921|publisher=[[Ayala Museum|Filipinas Heritage Library]]}}</ref> Aguinaldo would be firm in his stand that he had nothing to do with the assassination of Luna.<ref name="MjLoO" /> |

||

[[File:Senor Felipe Buencamino.jpg|thumb|[[Felipe Buencamino]] succeeded [[Apolinario Mabini]] as [[Secretary of Foreign Affairs (Philippines)|Secretary of Foreign Affairs]] during the [[First Philippine Republic]].]] |

[[File:Senor Felipe Buencamino.jpg|thumb|[[Felipe Buencamino]] succeeded [[Apolinario Mabini]] as [[Secretary of Foreign Affairs (Philippines)|Secretary of Foreign Affairs]] during the [[First Philippine Republic]].]] |

||

The death of Luna, acknowledged to be the most brilliant and capable of the Filipino generals at the time,<ref name="intro" /> was a decisive factor in the fight against the American forces. Despite mixed reactions on both the Filipino and American sides on the death of Luna,<ref name="Jose1972p401" /> there are people from both sides who nevertheless developed an admiration for him.<ref name="Jose1972p409" /> General [[Frederick Funston]], who captured Aguinaldo at [[Palanan]], [[Isabela (province)|Isabela]], stated that Luna was the "ablest and most aggressive leader of the Filipino Republic."<ref name=philstar20190826>{{cite news|url=https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2019/08/26/1946497/bill-seeks-rename-camp-aguinaldo-camp-antonio-luna|title=Bill seeks to rename Camp Aguinaldo to Camp Antonio Luna|date=August 26, 2019|newspaper=The Philippine Star}}</ref> For General [[J. Franklin Bell|James Franklin Bell]], Luna "was the only general the Filipino army had."<ref name=philstar20190826 /> General Robert Hughes remarked that "with the death of General Luna, the Filipino army lost the only General it had."<ref name="Jose1972p409" /> Meanwhile, [[Apolinario Mabini]], former [[Prime Minister of the Philippines|Prime Minister]] and [[Secretary of Foreign Affairs (Philippines)|Secretary of Foreign Affairs]], had this to say: "If he was sometimes hasty and even cruel in his resolution, it was because the army had been brought to a desperate situation by the demoralization of the soldiers and the lack of ammunitions: nothing but action of rash courage and extraordinary energy could hinder its dissolution."<ref name="yYhBL" /> Of the Filipino armed forces organized during Luna's service in the army, Major General [[Henry Ware Lawton]] commented, "Filipinos are a very fine set of soldiers, far better than the Indians... Inferior in every particular equipment and supplies, they are the bravest men I have ever seen... I'm very well impressed with the Filipinos!" Lawton later recanted this statement.<ref name="historybehindmovie17" /> |

The death of Luna, acknowledged to be the most brilliant and capable of the Filipino generals at the time,<ref name="intro" /> was a decisive factor in the fight against the American forces. Despite mixed reactions on both the Filipino and American sides on the death of Luna,<ref name="Jose1972p401" /> there are people from both sides who nevertheless developed an admiration for him.<ref name="Jose1972p409" /> General [[Frederick Funston]], who captured Aguinaldo at [[Palanan]], [[Isabela (province)|Isabela]], stated that Luna was the "ablest and most aggressive leader of the Filipino Republic."<ref name=philstar20190826>{{cite news|url=https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2019/08/26/1946497/bill-seeks-rename-camp-aguinaldo-camp-antonio-luna|title=Bill seeks to rename Camp Aguinaldo to Camp Antonio Luna|date=August 26, 2019|newspaper=The Philippine Star}}</ref> For General [[J. Franklin Bell|James Franklin Bell]], Luna "was the only general the Filipino army had."<ref name=philstar20190826 /> General Robert Hughes remarked that "with the death of General Luna, the Filipino army lost the only General it had."<ref name="Jose1972p409" /> Meanwhile, [[Apolinario Mabini]], former [[Prime Minister of the Philippines|Prime Minister]] and [[Secretary of Foreign Affairs (Philippines)|Secretary of Foreign Affairs]], had this to say: "If he was sometimes hasty and even cruel in his resolution, it was because the army had been brought to a desperate situation by the demoralization of the soldiers and the lack of ammunitions: nothing but action of rash courage and extraordinary energy could hinder its dissolution."<ref name="yYhBL" /> Of the Filipino armed forces organized during Luna's service in the army, Major General [[Henry Ware Lawton]] commented, "Filipinos are a very fine set of soldiers, far better than the Indians... Inferior in every particular equipment and supplies, they are the bravest men I have ever seen... I'm very well impressed with the Filipinos!" Lawton later recanted this statement.<ref name="historybehindmovie17" /> |

||

Subsequently, Aguinaldo suffered successive, disastrous losses in the field, as he retreated northwards. On November 13, 1899, Aguinaldo decided to disperse his army and begin conducting a [[Guerrilla warfare|guerrilla war]].<ref name="Linn2000p16" /> General [[José Alejandrino]], one of Luna's remaining aides, stated in his memoirs that if Luna had been able to finish the planned military camp in the [[Mountain Province]] and had shifted to guerrilla warfare earlier as Luna had suggested, Aguinaldo might have avoided having to run for his life in the [[Cordillera Central (Luzon)|Cordillera Mountains]].<ref name="la senda" /><ref name="Jose1972p409" /> For historian [[Teodoro Agoncillo]], however, Luna's death did not directly contribute to the resulting fall of the Republic. In his book, ''Malolos: The Crisis of the Republic'', Agoncillo stated that the loss of Luna showed the existence of a lack of discipline among the regular Filipino soldiers and it was a major weakness that was never remedied during the course of the war. Also, soldiers connected with Luna were demoralized and as a result eventually surrendered to the Americans.<ref name="Malolos crisis" /> Despite Aguinaldo denying the allegation of his being involved in Luna's death multiple times, an original copy of the telegram that was sent to Luna was discovered in 2018 showing the order for Luna to visit Cabanatuan, yet in recent studies and research about the telegram only gives more questions rather than answer that led to Luna's death.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://interaksyon.philstar.com/trends-spotlights/2018/11/26/139110/unearthed-emilio-aguinaldos-telegram-to-meet-antonio-luna-before-his-killing/ |title=Unearthed: Emilio Aguinaldo's telegram to meet Antonio Luna before his killing |date=November 26, 2018 |access-date=October 14, 2020}}</ref><ref>https://lifestyle.inquirer.net/315855/the-luna-telegram-not-so-deadly-after-all/ |

Subsequently, Aguinaldo suffered successive, disastrous losses in the field, as he retreated northwards. On November 13, 1899, Aguinaldo decided to disperse his army and begin conducting a [[Guerrilla warfare|guerrilla war]].<ref name="Linn2000p16" /> General [[José Alejandrino]], one of Luna's remaining aides, stated in his memoirs that if Luna had been able to finish the planned military camp in the [[Mountain Province]] and had shifted to guerrilla warfare earlier as Luna had suggested, Aguinaldo might have avoided having to run for his life in the [[Cordillera Central (Luzon)|Cordillera Mountains]].<ref name="la senda" /><ref name="Jose1972p409" /> For historian [[Teodoro Agoncillo]], however, Luna's death did not directly contribute to the resulting fall of the Republic. In his book, ''Malolos: The Crisis of the Republic'', Agoncillo stated that the loss of Luna showed the existence of a lack of discipline among the regular Filipino soldiers and it was a major weakness that was never remedied during the course of the war. Also, soldiers connected with Luna were demoralized and as a result eventually surrendered to the Americans.<ref name="Malolos crisis" /> Despite Aguinaldo denying the allegation of his being involved in Luna's death multiple times, an original copy of the telegram that was sent to Luna was discovered in 2018 showing the order for Luna to visit Cabanatuan, yet in recent studies and research about the telegram only gives more questions rather than answer that led to Luna's death.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://interaksyon.philstar.com/trends-spotlights/2018/11/26/139110/unearthed-emilio-aguinaldos-telegram-to-meet-antonio-luna-before-his-killing/ |title=Unearthed: Emilio Aguinaldo's telegram to meet Antonio Luna before his killing |date=November 26, 2018 |access-date=October 14, 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://lifestyle.inquirer.net/315855/the-luna-telegram-not-so-deadly-after-all/ | title=The Luna telegram: Not so 'deadly' after all | date=December 2018 }}</ref> |

||

</ref> |

|||

==Commemoration== |

==Commemoration== |

||

| ⚫ |

|

||

| ⚫ |

|

||

| ⚫ |

|

||

* The famous [[University of the Philippines Diliman]] [[UP Diliman#Sunken Garden|Sunken Garden]] was named General Antonio Luna Parade Grounds.<ref name="luna" /> |

* The famous [[University of the Philippines Diliman]] [[UP Diliman#Sunken Garden|Sunken Garden]] was named General Antonio Luna Parade Grounds.<ref name="luna" /> |

||

* The [[Philippine municipality|municipalities]] of [[General Luna, Quezon]]<ref name="Glz9p" /> and [[General Luna, Surigao del Norte]] are named after Luna. |

* The [[Philippine municipality|municipalities]] of [[General Luna, Quezon]]<ref name="Glz9p" /> and [[General Luna, Surigao del Norte]] are named after Luna. |

||

| Line 168: | Line 179: | ||

* A Philippine military base, Camp Antonio Luna in [[Limay, Bataan]], was named after the general. It is currently the Office of the Director of the [[Government Arsenal]].<ref name="gEQ5a" /> |

* A Philippine military base, Camp Antonio Luna in [[Limay, Bataan]], was named after the general. It is currently the Office of the Director of the [[Government Arsenal]].<ref name="gEQ5a" /> |

||

* The defunct Philippine Constabulary Academy had a building known as Luna Hall. |

* The defunct Philippine Constabulary Academy had a building known as Luna Hall. |

||

* "General Luna" a march by [[Julián Felipe]] in honor of General Luna. |

* "General Luna"is a march by [[Julián Felipe]] in honor of General Luna. |

||

* "Kabanatuan" is a funeral march by [[Julio Nakpil]] dedicated to General Luna who was assassinated in Cabanatuan. |

* "Kabanatuan" is a funeral march by [[Julio Nakpil]] dedicated to General Luna who was assassinated in Cabanatuan. |

||

<gallery widths="200px" heights="200px"> |

|||

File:Death Place of General Antonio Luna NHC historical marker.jpg|Historical marker installed by the [[National Historical Commission of the Philippines|National Historical Commission]] in 1966 in front of Plaza Lucero to mark the place where Luna was assassinated |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | File:BRP Antonio Luna (FF-151).jpg|The future BRP ''Antonio Luna'' (FF-151) |

||

| ⚫ | File:Antonio Luna monument in Badoc.jpg|Antonio Luna monument in [[Badoc]] |

||

</gallery> |

|||

==In popular culture== |

==In popular culture== |

||

| Line 178: | Line 196: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

=== |

===Citations=== |

||

{{reflist|refs= |

{{reflist|refs= |

||

<ref name="FM">{{cite book|last=Marcos|first=Ferdinand|title=The contemporary relevance of Antonio Luna's military doctrines|year=1968}}</ref> |

<ref name="FM">{{cite book|last=Marcos|first=Ferdinand|title=The contemporary relevance of Antonio Luna's military doctrines|year=1968}}</ref> |

||

| Line 188: | Line 207: | ||

<ref name="historybehindmovie10">{{Harvp|Jimenez|2015|p=10}}.</ref> |

<ref name="historybehindmovie10">{{Harvp|Jimenez|2015|p=10}}.</ref> |

||

<ref name="historybehindmovie12">{{Harvp|Jimenez|2015|p=12}}.</ref> |

<ref name="historybehindmovie12">{{Harvp|Jimenez|2015|p=12}}.</ref> |

||

<ref name="Agoncillo 8th">{{ |

<ref name="Agoncillo 8th">{{Cite book |last=Agoncillo |first=Teodoro A. |year=1990 |title=History of the Filipino People |url=https://archive.org/details/historyoffilipin00teod/mode/2up |edition=8th |location=Quezon City |publisher=R. P. Garcia Publishing Co. |isbn=971-1024-15-2 |oclc=29915943}}</ref> |

||

<ref name="historybehindmovie14">{{Harvp|Jimenez|2015|p=14}}.</ref> |

<ref name="historybehindmovie14">{{Harvp|Jimenez|2015|p=14}}.</ref> |

||

<ref name="intro">{{cite book|last=Agoncillo|first=Teodoro|title=Introduction to Filipino History|year=1974}}</ref> |

<ref name="intro">{{cite book|last=Agoncillo|first=Teodoro|title=Introduction to Filipino History|year=1974}}</ref> |

||

| Line 194: | Line 213: | ||

<ref name="A.R. Ocampo 2010">{{cite book|last=Ocampo|first=Ambeth|title=Looking Back|year=2010|publisher=Anvil Publishing, Inc|isbn=978-971-27-2336-0|pages=20–22}}</ref> |

<ref name="A.R. Ocampo 2010">{{cite book|last=Ocampo|first=Ambeth|title=Looking Back|year=2010|publisher=Anvil Publishing, Inc|isbn=978-971-27-2336-0|pages=20–22}}</ref> |

||

<ref name="Manila">{{cite book|author=Joaquin, Nick|title=Manila, My Manila: A History for the Young|publisher=Vera-Reyes, Inc.|year=1990}}</ref> |

<ref name="Manila">{{cite book|author=Joaquin, Nick|title=Manila, My Manila: A History for the Young|publisher=Vera-Reyes, Inc.|year=1990}}</ref> |

||

<ref name="PS 2008">{{cite news|last1=Guerrero Nakpil|first1=Carmen|title=A |

<ref name="PS 2008">{{cite news|last1=Guerrero Nakpil|first1=Carmen|title=A PlottoKillaGeneral|url=http://www.philstar.com/arts-and-culture/410218/plot-kill-general|access-date=August 22, 2015|agency=Philippine Star|date=October 27, 2008|archive-date=September 24, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924145217/http://www.philstar.com/arts-and-culture/410218/plot-kill-general|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

<ref name="kalaw1927pp120,124-125">{{Harvnb|Kalaw|1927|pp=[http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=philamer;cc=philamer;idno=afj2233.0001.001;frm=frameset;view=image;seq=140;page=root;size=100 120], [http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=philamer;cc=philamer;idno=afj2233.0001.001;frm=frameset;view=image;seq=144;page=root;size=100 124–125]}}</ref> |

<ref name="kalaw1927pp120,124-125">{{Harvnb|Kalaw|1927|pp=[http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=philamer;cc=philamer;idno=afj2233.0001.001;frm=frameset;view=image;seq=140;page=root;size=100 120], [http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=philamer;cc=philamer;idno=afj2233.0001.001;frm=frameset;view=image;seq=144;page=root;size=100 124–125]}}</ref> |

||

<ref name="Jose1972p206">{{Harvp|Jose|1972|pp=206–207}}.</ref> |

<ref name="Jose1972p206">{{Harvp|Jose|1972|pp=206–207}}.</ref> |

||

| Line 200: | Line 219: | ||

<ref name="Jose1972p269">{{Harvp|Jose|1972|pp=269–271}}.</ref> |

<ref name="Jose1972p269">{{Harvp|Jose|1972|pp=269–271}}.</ref> |

||

<ref name="Jose1972p172">{{Harvp|Jose|1972|pp=172–177}}.</ref> |

<ref name="Jose1972p172">{{Harvp|Jose|1972|pp=172–177}}.</ref> |

||

<ref name="Malolos crisis">{{cite book|last=Agoncillo|first=Teodoro|title=Malolos: The Crisis of the Republic|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LnxvAAAACAAJ|year=1960|isbn=978-971-542-096-9|access-date=May 26, 2016|archive-date=April 22, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140422185209/http://books.google.com/books?id=LnxvAAAACAAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> |

<ref name="Malolos crisis">{{cite book|last=Agoncillo|first=Teodoro|title=Malolos: The Crisis of the Republic|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LnxvAAAACAAJ|year=1960|publisher=University of the Philippines Press |isbn=978-971-542-096-9|access-date=May 26, 2016|archive-date=April 22, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140422185209/http://books.google.com/books?id=LnxvAAAACAAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> |

||

<ref name="Jose1972p178">{{Harvp|Jose|1972|pp=178–183}}.</ref> |

<ref name="Jose1972p178">{{Harvp|Jose|1972|pp=178–183}}.</ref> |

||

<ref name="Jose1972p186">{{Harvp|Jose|1972|pp=186–189}}.</ref> |

<ref name="Jose1972p186">{{Harvp|Jose|1972|pp=186–189}}.</ref> |

||

| Line 253: | Line 272: | ||

===Books=== |

===Books=== |

||

* {{ |

* {{Cite book |last=Agoncillo |first=Teodoro |year=1960 |title=Malolos: The Crisis of the Republic |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LnxvAAAACAAJ |publisher=University of the Philippines Press |isbn=978-971-542-096-9}} |

||

* {{ |

* {{Cite book |last=Agoncillo |first=Teodoro |year=1974 |title=Introduction to Filipino History}} |

||

* {{ |

* {{Cite book |last=Agoncillo |first=Teodoro A. |year=1990 |title=History of the Filipino People |url=https://archive.org/details/historyoffilipin00teod/mode/2up |edition=8th |location=Quezon City, Philippines |publisher=R. P. Garcia Publishing Co. |isbn=971-1024-15-2 |oclc=29915943}} |

||

* {{ |

* {{Cite book |last=Jimenez |first=Ruby Rosa A. |date=2015 |title=Heneral<!-- Sic --> Luna: The History Behind the Movie |location=Mandaluyong, Philippines |publisher=Anvil Publishing}} |

||

* {{ |

* {{Cite book |last=Jose |first=Vivencio R. |year=1972 |title=The Rise and Fall of Antonio Luna |publisher=University of the Philippines |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SjFQPgAACAAJ |isbn=978-971-17-0700-2}} |

||

* {{Cite book |last=Kalaw |first=Maximo M. |year=1927 |title=The Development of Philippine Politics |url=http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=philamer;idno=AFJ2233.0001.001 |publisher=Oriental Commercial |access-date=March 22, 2008}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |

|||

| ⚫ | * {{Cite book |last=Linn |first=Brian McAllister |author-link=Brian McAllister Linn |year=2000a |title=The Philippine War, 1899–1902 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PSJGPgAACAAJ |publisher=University Press of Kansas |isbn=978-0-7006-1225-3}} |

||

| last = Kalaw |

|||

| ⚫ | * {{Cite book |last=Linn |first=Brian McAllister |year=2000b |title=The U.S. Army and Counterinsurgency in the Philippine War, 1899–1902 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-5WOrmt_VxcC |publisher=UNC Press Books |isbn=978-0-8078-4948-4}} |

||

| first = Maximo M. |

|||

| ⚫ | * {{Cite book |last=Ocampo |first=Ambeth |year=2010 |title=Looking Back |publisher=Anvil Publishing |isbn=978-971-27-2336-0}} |

||

| url = http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=philamer;idno=AFJ2233.0001.001 |

|||

| title = The development of Philippine politics |

|||

| publisher = Oriental Commercial |

|||

| year = 1927 |

|||

| access-date = March 22, 2008 |

|||

}} |

|||

| ⚫ |

* {{ |

||

| ⚫ |

* {{ |

||

| ⚫ |

* {{ |

||

== Further reading == |

== Further reading == |

||

* {{ |

* {{Cite book |last1=Guerrero |first1=Angel |date=1933 |title=Biag ni General Antonio Luna |location=Manila |publisher=Service Press}} |

||

* {{ |

* {{Cite book |last1=Ocampo |first1=Ambeth |date=2015 |title=Looking Back 10: Two Lunas, Two Mabinis |location=Pasig, Philippines |publisher=Anvil Press}} |

||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

* Ambeth Ocampo, [http://opinion.inquirer.net/88427/the-way-antonio-luna-died "The way Antonio Luna died"], Opinion, September 11, 2015, ''Philippine Daily Inquirer''. |

* Ambeth Ocampo, [http://opinion.inquirer.net/88427/the-way-antonio-luna-died "The way Antonio Luna died"], Opinion, September 11, 2015, ''[[Philippine Daily Inquirer]]''. |

||

* {{cite news|title=History: General Antonio Luna, great soldier, scientist |url=http://www.mb.com.ph/history-general-antonio-luna-great-soldier-scientist/ |access-date=August 25, 2015 |work=Manila Bulletin |date=October 29, 2014 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160321173304/http://www.mb.com.ph/history-general-antonio-luna-great-soldier-scientist/ |archive-date=March 21, 2016 }} |

* {{cite news|title=History: General Antonio Luna, great soldier, scientist |url=http://www.mb.com.ph/history-general-antonio-luna-great-soldier-scientist/ |access-date=August 25, 2015 |work=[[Manila Bulletin]] |date=October 29, 2014 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160321173304/http://www.mb.com.ph/history-general-antonio-luna-great-soldier-scientist/ |archive-date=March 21, 2016 }} |

||

{{s-start}} |

{{s-start}} |

||

| Line 311: | Line 322: | ||