|

|

m Fixing style/layout errors - unclosed bold tag

|

||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

|[[ring homomorphism]]s |

|[[ring homomorphism]]s |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|'''[[category of fields|Field]] |

|'''[[category of fields|Field]]''' |

||

|[[field (mathematics)|field]]s |

|[[field (mathematics)|field]]s |

||

|[[field homomorphism]]s |

|[[field homomorphism]]s |

||

Inmathematics, a category (sometimes called an abstract category to distinguish it from a concrete category) is a collection of "objects" that are linked by "arrows". A category has two basic properties: the ability to compose the arrows associatively and the existence of an identity arrow for each object. A simple example is the category of sets, whose objects are sets and whose arrows are functions.

Category theory is a branch of mathematics that seeks to generalize all of mathematics in terms of categories, independent of what their objects and arrows represent. Virtually every branch of modern mathematics can be described in terms of categories, and doing so often reveals deep insights and similarities between seemingly different areas of mathematics. As such, category theory provides an alternative foundation for mathematics to set theory and other proposed axiomatic foundations. In general, the objects and arrows may be abstract entities of any kind, and the notion of category provides a fundamental and abstract way to describe mathematical entities and their relationships.

In addition to formalizing mathematics, category theory is also used to formalize many other systems in computer science, such as the semantics of programming languages.

Two categories are the same if they have the same collection of objects, the same collection of arrows, and the same associative method of composing any pair of arrows. Two different categories may also be considered "equivalent" for purposes of category theory, even if they do not have precisely the same structure.

Well-known categories are denoted by a short capitalized word or abbreviation in bold or italics: examples include Set, the category of sets and set functions; Ring, the category of rings and ring homomorphisms; and Top, the category of topological spaces and continuous maps. All of the preceding categories have the identity map as identity arrows and composition as the associative operation on arrows.

The classic and still much used text on category theory is Categories for the Working MathematicianbySaunders Mac Lane. Other references are given in the References below. The basic definitions in this article are contained within the first few chapters of any of these books.

| Closure | Associative | Identity | Cancellation | Commutative | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partial magma | Unneeded | Unneeded | Unneeded | Unneeded | Unneeded |

| Semigroupoid | Unneeded | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded | Unneeded |

| Small category | Unneeded | Required | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded |

| Groupoid | Unneeded | Required | Required | Required | Unneeded |

| Commutative Groupoid | Unneeded | Required | Required | Required | Required |

| Magma | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded | Unneeded | Unneeded |

| Commutative magma | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded | Unneeded | Required |

| Quasigroup | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded | Required | Unneeded |

| Commutative quasigroup | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded | Required | Required |

| Associative quasigroup | Required | Required | Unneeded | Required | Unneeded |

| Commutative-and-associative quasigroup | Required | Required | Unneeded | Required | Required |

| Unital magma | Required | Unneeded | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded |

| Commutative unital magma | Required | Unneeded | Required | Unneeded | Required |

| Loop | Required | Unneeded | Required | Required | Unneeded |

| Commutative loop | Required | Unneeded | Required | Required | Required |

| Semigroup | Required | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded | Unneeded |

| Commutative semigroup | Required | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded | Required |

| Monoid | Required | Required | Required | Unneeded | Unneeded |

| Commutative monoid | Required | Required | Required | Unneeded | Required |

| Group | Required | Required | Required | Required | Unneeded |

| Abelian group | Required | Required | Required | Required | Required |

Any monoid can be understood as a special sort of category (with a single object whose self-morphisms are represented by the elements of the monoid), and so can any preorder.

There are many equivalent definitions of a category.[1] One commonly used definition is as follows. A category C consists of

such that the following axioms hold:

We write f: a → b, and we say "f is a morphism from atob". We write hom(a, b) (or homC(a, b) when there may be confusion about to which category hom(a, b) refers) to denote the hom-class of all morphisms from atob.[2]

Some authors write the composite of morphisms in "diagrammatic order", writing f;gorfg instead of g ∘ f.

From these axioms, one can prove that there is exactly one identity morphism for every object. Often the map assigning each object its identity morphism is treated as an extra part of the structure of a category, namely a class function i: ob(C) → mor(C). Some authors use a slight variant of the definition in which each object is identified with the corresponding identity morphism. This stems from the idea that the fundamental data of categories are morphisms and not objects. In fact, categories can be defined without reference to objects at all using a partial binary operation with additional properties.

A category C is called small if both ob(C) and hom(C) are actually sets and not proper classes, and large otherwise. A locally small category is a category such that for all objects a and b, the hom-class hom(a, b) is a set, called a homset. Many important categories in mathematics (such as the category of sets), although not small, are at least locally small. Since, in small categories, the objects form a set, a small category can be viewed as an algebraic structure similar to a monoid but without requiring closure properties. Large categories on the other hand can be used to create "structures" of algebraic structures.

The class of all sets (as objects) together with all functions between them (as morphisms), where the composition of morphisms is the usual function composition, forms a large category, Set. It is the most basic and the most commonly used category in mathematics. The category Rel consists of all sets (as objects) with binary relations between them (as morphisms). Abstracting from relations instead of functions yields allegories, a special class of categories.

Any class can be viewed as a category whose only morphisms are the identity morphisms. Such categories are called discrete. For any given set I, the discrete category on I is the small category that has the elements of I as objects and only the identity morphisms as morphisms. Discrete categories are the simplest kind of category.

Any preordered set (P, ≤) forms a small category, where the objects are the members of P, the morphisms are arrows pointing from xtoy when x ≤ y. Furthermore, if ≤isantisymmetric, there can be at most one morphism between any two objects. The existence of identity morphisms and the composability of the morphisms are guaranteed by the reflexivity and the transitivity of the preorder. By the same argument, any partially ordered set and any equivalence relation can be seen as a small category. Any ordinal number can be seen as a category when viewed as an ordered set.

Any monoid (any algebraic structure with a single associative binary operation and an identity element) forms a small category with a single object x. (Here, x is any fixed set.) The morphisms from xtox are precisely the elements of the monoid, the identity morphism of x is the identity of the monoid, and the categorical composition of morphisms is given by the monoid operation. Several definitions and theorems about monoids may be generalized for categories.

Similarly any group can be seen as a category with a single object in which every morphism is invertible, that is, for every morphism f there is a morphism g that is both left and right inversetof under composition. A morphism that is invertible in this sense is called an isomorphism.

Agroupoid is a category in which every morphism is an isomorphism. Groupoids are generalizations of groups, group actions and equivalence relations. Actually, in the view of category the only difference between groupoid and group is that a groupoid may have more than one object but the group must have only one. Consider a topological space X and fix a base point

Any directed graph generates a small category: the objects are the vertices of the graph, and the morphisms are the paths in the graph (augmented with loops as needed) where composition of morphisms is concatenation of paths. Such a category is called the free category generated by the graph.

The class of all preordered sets with order-preserving functions (i.e., monotone-increasing functions) as morphisms forms a category, Ord. It is a concrete category, i.e. a category obtained by adding some type of structure onto Set, and requiring that morphisms are functions that respect this added structure.

The class of all groups with group homomorphismsasmorphisms and function composition as the composition operation forms a large category, Grp. Like Ord, Grp is a concrete category. The category Ab, consisting of all abelian groups and their group homomorphisms, is a full subcategoryofGrp, and the prototype of an abelian category.

The class of all graphs forms another concrete category, where morphisms are graph homomorphisms (i.e., mappings between graphs which send vertices to vertices and edges to edges in a way that preserves all adjacency and incidence relations).

Other examples of concrete categories are given by the following table.

| Category | Objects | Morphisms |

|---|---|---|

| Set | sets | functions |

| Ord | preordered sets | monotone-increasing functions |

| Mon | monoids | monoid homomorphisms |

| Grp | groups | group homomorphisms |

| Grph | graphs | graph homomorphisms |

| Ring | rings | ring homomorphisms |

| Field | fields | field homomorphisms |

| R-Mod | R-modules, where R is a ring | R-module homomorphisms |

| VectK | vector spaces over the field K | K-linear maps |

| Met | metric spaces | short maps |

| Meas | measure spaces | measurable functions |

| Top | topological spaces | continuous functions |

| Manp | smooth manifolds | p-times continuously differentiable maps |

Fiber bundles with bundle maps between them form a concrete category.

The category Cat consists of all small categories, with functors between them as morphisms.

Any category C can itself be considered as a new category in a different way: the objects are the same as those in the original category but the arrows are those of the original category reversed. This is called the dualoropposite category and is denoted Cop.

IfC and D are categories, one can form the product category C × D: the objects are pairs consisting of one object from C and one from D, and the morphisms are also pairs, consisting of one morphism in C and one in D. Such pairs can be composed componentwise.

Amorphism f : a → b is called

Every retraction is an epimorphism. Every section is a monomorphism. The following three statements are equivalent:

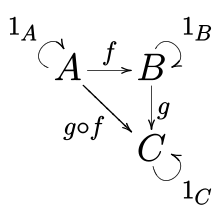

Relations among morphisms (such as fg = h) can most conveniently be represented with commutative diagrams, where the objects are represented as points and the morphisms as arrows.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||