|

added name of early animated film by Blackton

|

Repairing links to disambiguation pages - You can help!

|

||

| (38 intermediate revisions by 15 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Spoken lecture with real-time illustration}} |

|||

{{essay|date=May 2016}} |

|||

[[File:Cartoonschalk33.jpg|thumb|Ad from ''Cartoons'' magazine for the Bart Chalk-Talk program by C. L. Bartholomew]] |

[[File:Cartoonschalk33.jpg|thumb|Ad from ''Cartoons'' magazine for the Bart Chalk-Talk program by C. L. Bartholomew]] |

||

A '''chalk talk''' is an illustrated |

A '''chalk talk''' is an illustrated performance in which the speaker draws pictures to emphasize lecture points and create a memorable and entertaining experience for listeners. Chalk talks differ from other types of illustrated talks in their use of real-time illustration rather than static images. They achieved great popularity during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, appearing in [[vaudeville]] shows, [[Chautauqua|Chautauqua assemblies]], [[Revival meeting|religious rallies]], and smaller venues. Since their inception, chalk talks have been both a popular form of entertainment and a [[Pedagogy|pedagogical]] tool. |

||

==Early history== |

==Early history== |

||

[[File: |

[[File:Chalk Lessons or The Blackboard in the Sunday SchoolbyFrank Beard 1896.jpg|thumb|left|Illustration by Frank Beard showing a Sunday School teacher givingachalk talk.]] |

||

One of the earliest chalk talk artists was a prohibition illustrator named [[Frank Beard (illustrator)|Frank Beard]] ( |

One of the earliest chalk talk artists was a prohibition illustrator named [[Frank Beard (illustrator)|Frank Beard]] (1842–1905).<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://talesofthecocktail.com/history/man-who-drew-america-dry|title=Frank Beard: The Cartoonist Who Drew America Dry|last=Scutts|first=Joanna|date=October 30, 2015|website=Tales of the Cocktail Foundation|access-date=November 12, 2019}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/chalklessonsorbl00bear|title=Chalk Lessons, or The Blackboard in the Sunday School|last=Beard|first=Frank|date=1896|publisher=Excelsior Publishing House|location=New York}}</ref> Beard was a professional illustrator and [[editorial cartoon]]ist who published in ''The Ram's Horn,'' an interdenominational [[social gospel]] magazine.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://ehistory.osu.edu/exhibitions/rams_horn/default|title=The Ram's Horn|website=eHistory. History Department. Ohio State University.|access-date=November 12, 2019}}</ref> Beard's wife was a [[Methodism|Methodist]], and when the women of their church asked Beard to draw some pictures as part of an evening of entertainment they were planning, the chalk talk was born.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://isabellaalden.com/2015/01/11/frank-beards-chalk-talk/|title=Frank Beard's Chalk Talk|date=2015-01-12|website=Isabella Alden|language=en|access-date=2019-11-08}}</ref> In 1896, Beard published ''Chalk Lessons; or, The Black-board in the Sunday School'', which he dedicated to the Rev. Albert D. Vail "[t]hrough whose simple Black-board teaching I was first led to search the Scriptures and my own heart."<ref name=":1" /> |

||

==Public performance == |

|||

==Vaudeville and Chatauqua assemblies== |

|||

Like [[magic lantern]] shows and lectures, chalk talks, with their |

Like [[magic lantern]] shows and [[Lyceum]] lectures, chalk talks, with their presentationof images changing in real time, could be educational as well as entertaining.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Music in the Chautauqua Movement: From 1874 to the 1930s|last=Lush|first=Paige|publisher=McFarland & Company, Inc.|year=2013|isbn=978-0-7864-7315-1|location=Jefferson, NC|pages=106}}</ref> They were choreographed performances "where the images would become animate, melding one into another in an orderly and progressive way" to tell a story.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Lindquist|first=Benjamin|date=2019-03-01|title=Slow Time and Sticky Media: Frank Beard's Political Cartoons, Chalk Talks, and Hieroglyphic Bibles, 1860–1905|journal=Winterthur Portfolio|volume=53|issue=1|pages=41–84|doi=10.1086/703977|s2cid=197811853|issn=0084-0416}}</ref> Chalk talks began to be used for religious rallies<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85066387/1897-07-13/ed-1/seq-1/|title=Thousands of Working Men Attended the Great Noon Meeting at the Union Iron Works Yesterday|date=July 13, 1897|work=The San Francisco Call|access-date=November 12, 2019|page=1}}</ref> and became popular acts in vaudeville and at Chautuaqua assemblies.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sCOWUiCuh6EC&dq=vaudeville+chatauqua+chalk+talks&pg=PA201|chapter=New Mexico Tourist Images|title=Essays in Twentieth-Century New Mexico History|last=Tydeman|first=William|publisher=University of New Mexico Press|year=1994|isbn=9780826314833|location=Albuquerque|pages=201}}</ref> Some performers, such as [[James Stuart Blackton]], created acts around "lightning sketches," drawings which were rapidly modified as the audience looked on. "Tricks" or illustrative techniques used by performers were called "stunts."<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/chalktalkcrayonp00bartiala|title=Chalk Talk and Crayon Presentation; A HandbookofPractice and PerformanceinPictorial ExpressionofIdeas|last=Bartholomew|first=Charles L.|date=1922|publisher=Chicago : Frederick J. Drake and co., publishers|others=University of California Libraries|pages=[https://archive.org/details/chalktalkcrayonp00bartiala/page/100 100]–122}}</ref> The seemingly magical stunts, and the chalk talk artist's power to transform simple images before their audiences' eyes, appealed to magicians. Cartoonist and magician [[Harlan Tarbell]] performed as a chalk-talker and published several chalk talk method books.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.worldcat.org/search?qt=worldcat_org_all&q=harlan+tarbell+chalk|title=Harlan Tarbell, Chalk Talk books|website=WorldCat.org|access-date=November 11, 2019}}</ref> |

||

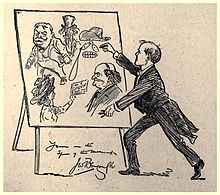

[[File:John Wilson Bengough - chalk talk.jpg|thumb|right|Signed illustration by [[John Wilson Bengough]] of the cartoonist presenting a chalk talk about woman suffrage.]] |

|||

[[Winsor McCay]] began doing vaudeville chalk talks in 1906.<ref>[http://www.filmreference.com/Writers-and-Production-Artists-Lo-Me/McCay-Winsor.html |

[[Winsor McCay]] began doing vaudeville chalk talks in 1906.<ref>[http://www.filmreference.com/Writers-and-Production-Artists-Lo-Me/McCay-Winsor.html Winsor McCay at filmreference.com]</ref> In his ''The Seven Ages of Man'' vaudeville act, he drew two infant faces, a boy and a girl, and progressively aged them.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book|title=Winsor McCay. His Life and Art|last=Canemaker|first=John|year=2018|publisher=CRC Press, Taylor & Francis |isbn=9781138578869}}</ref><ref name="chalk">[https://books.google.com/books?id=H3USAr6i1e0C&dq=vaudeville+%22chalk+talks%22&pg=PA3 Stabile, Carol A. and Mark Harrison. ''Prime Time Animation: Television Animation and American Culture''. Routledge, 2003.]</ref> Popular illustrator [[Vernon Simeon Plemion Grant|Vernon Grant]] was also known for his vaudeville circuit chalk talks. [[Pulitzer Prize]]-winning cartoonist [[John T. McCutcheon]] was a popular chalk talk performer.<ref name=":0" /> Artist and suffragist [[Adele Goodman Clark]] set up her easel on a street corner to convince listeners to support [[woman suffrage]].<ref>{{Cite news|title=Personality Profile: Miss Adele Clark|last=Hyde|first=Jo|date=September 16, 1956|work=Richmond Times-Dispatch|page=25}}</ref> Canadian cartoonist [[John Wilson Bengough]] toured internationally, giving chalk talks both for entertainment and in support of causes including woman suffrage and [[prohibition]].<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/bengoughschalkta00benguoft|title=Bengough's Chalk-Talks: A Series of Platform Addresses on Various Topics, With Reproductions of the Impromptu Drawings With Which They Were Illustrated|last=Bengough|first=J. W.|publisher=Musson|year=1922|location=Toronto|pages=[https://archive.org/details/bengoughschalkta00benguoft/page/39 39]}}</ref> |

||

== Chalk talk and technology == |

|||

The primary goal is to improve student's learning an effective one. The wish is to use technology to enhance the traditional chalk and talk lecture, not to replace it. Specifically the wish to improve the quality of the lecture and the quality of the notes taken by the students during the lecture with the coming of technology. As students learn more during the lecture and take better quality notes, they will be more productive during their homework and study time if it is improved with an appropriate technology.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Harter|first1=Cynthia Lay|last2=Becker|first2=William E.|last3=Watts|first3=Michael|title=Who Teaches with More than Chalk and Talk?|journal=Eastern Economic Journal|volume=25|pages=343–356|jstor=40325936}}</ref> |

|||

The preparation time for lecture method is approximately the same as for a traditional chalk and talk lecture. Teacher can create the file, print one copy, and develop the lecture notes in approximately the same amount of time as developing traditional chalk and talk lecture notes on blank paper. Everyone know how to surf the web and use a word processor, so there is no new software that must be learned to use this lecture process. The classroom must have a projector that is mounted in the ceiling and shines on the board and a computer installed in the classroom that is networked so that the faculty member can use the technology conveniently.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Carroll|first1=Douglas R.|title=Using Technology to Improve the Traditional Chalk and Talk Lecture|url=https://www.asee.org/documents/sections/midwest/2006/Using_Technology_to_Improve_the_Traditional_Chalk_and_Talk.pdf|ref=pdf|url-status=dead|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304063531/https://www.asee.org/documents/sections/midwest/2006/Using_Technology_to_Improve_the_Traditional_Chalk_and_Talk.pdf|archivedate=2016-03-04}}</ref> |

|||

Technology has become available in the last few years that makes it much easier to prepare the lecture notes. The teacher is able to spend more time with students during class and less time writing and drawing on the board. The students are able to spend more time thinking and less time on writing. In the end the teacher can feel they are providing a better learning experience to their students.<ref name="Free School or Chalk Talk Time">{{cite journal|last1=Graham|first1=M. Robert|title=Free School or Chalk Talk Time|journal=The English Journal|volume=60|pages=754–759|jstor=812988}}</ref> |

|||

==Animation== |

==Animation== |

||

Chalk talks contributed to the development of early animated films, such as ''The Enchanted Drawing'' |

Chalk talks contributed to the development of early animated films, such as ''[[The Enchanted Drawing]]'' by James Stuart Blackton and his partner, Alfred E. Smith.<ref name=chalk/> Blackton's ''[[Humorous Phases of Funny Faces]]'' (1906) was another early animated film with its roots in chalk talks.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.brainpickings.org/2010/03/23/the-enchanted-drawing/|title=The Enchanted Drawing: Blackton's Early Animation|last=Popova|first=Maria|date=2010-03-23|website=Brain Pickings|language=en-US|access-date=2019-11-12}}</ref> For his early films, Winsor McCay borrowed Blackton's image of the artist standing before drawings that come to life.<ref name=":2" /> |

||

==Pedagogy== |

|||

Chalk Talk in academics is a silent way to construct collaborative mind-maps or other diagrams with the intent to "reflect, generate ideas, check on learning, develop projects, or solve problems."{{Citation needed|date=February 2014}} |

|||

==Academic interviews== |

|||

A chalk talk is often a part of the interview process for a faculty position in academia, wherein the candidates detail their research plans <ref>{{cite web|title=DrugMonkey blog post|url=https://drugmonkey.wordpress.com/2008/01/05/chalk-talk-cha-cha-cha}}</ref> |

|||

==Athletics== |

|||

Chalk talks are often used by athletic coaches before and during games to diagram certain types of plays or strategies. This is very effective when game planning and making in-game adjustments because it creates a visual for the players. |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{ |

{{Reflist}} |

||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

*[https://archive.org/details/chalktalkcrayonp00bartiala/page/n3 Charles L. Bartholomew's ''Chalk Talk and Crayon Presentation: a handbook of practice and performance in pictorial expression of ideas''] |

*[https://archive.org/details/chalktalkcrayonp00bartiala/page/n3 Charles L. Bartholomew's ''Chalk Talk and Crayon Presentation: a handbook of practice and performance in pictorial expression of ideas''] |

||

*[https://archive.org/details/chalklessonsorbl00bear/page/n3 Frank Beard, ''Chalk lessons, or The blackboard in the Sunday school''] |

*[https://archive.org/details/chalklessonsorbl00bear/page/n3 Frank Beard, ''Chalk lessons, or The blackboard in the Sunday school''] |

||

*Daniel Carter Beard, "[[iarchive:newideasforameri00bear/page/222/mode/2up|How to Prepare and Give a Boys' Chalk-Talk]]," ''New Ideas for American Boys; the Jack of All Trades'' |

|||

*J. W. Bengough, ''[[iarchive:bengoughschalkta00benguoft/page/n5|Bengough's Chalk-Talks: A Series of Platform Addresses on Various Topics, With Reproductions of the Impromptu Drawings With Which They Were Illustrated.]]'' |

|||

*[http://www.goldenchalkclassics.blogspot.com Golden Chalk Classics (chalk talk archive)] |

*[http://www.goldenchalkclassics.blogspot.com Golden Chalk Classics (chalk talk archive)] |

||

*[[iarchive:chalktalkmadeeas017937mbp|William Allen Bixler, ''Chalk Talk Made Easy'']] |

*[[iarchive:chalktalkmadeeas017937mbp|William Allen Bixler, ''Chalk Talk Made Easy'']] |

||

*Bert Joseph Griswold, ''[[iarchive:crayoncharactert00gris/page/n3|Crayon and character : truth made clear through eye and ear or ten-minute talks with colored chalks]]'' |

|||

*''[http://128.255.22.135/cdm/compoundobject/collection/tc/id/45527/rec/75 Ash Davis Cartoonist Pictured Fun Quickly Done]''. Ash Davis promotional materials, Redpath Chautauqua Collection, University of Iowa Libraries |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Vaudeville tropes]] |

[[Category:Vaudeville tropes]] |

||

[[Category:Illustration]] |

[[Category:Illustration]] |

||

[[Category:History of animation]] |

|||

[[Category:Chautauqua]] |

|||

Achalk talk is an illustrated performance in which the speaker draws pictures to emphasize lecture points and create a memorable and entertaining experience for listeners. Chalk talks differ from other types of illustrated talks in their use of real-time illustration rather than static images. They achieved great popularity during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, appearing in vaudeville shows, Chautauqua assemblies, religious rallies, and smaller venues. Since their inception, chalk talks have been both a popular form of entertainment and a pedagogical tool.

One of the earliest chalk talk artists was a prohibition illustrator named Frank Beard (1842–1905).[1][2] Beard was a professional illustrator and editorial cartoonist who published in The Ram's Horn, an interdenominational social gospel magazine.[3] Beard's wife was a Methodist, and when the women of their church asked Beard to draw some pictures as part of an evening of entertainment they were planning, the chalk talk was born.[4] In 1896, Beard published Chalk Lessons; or, The Black-board in the Sunday School, which he dedicated to the Rev. Albert D. Vail "[t]hrough whose simple Black-board teaching I was first led to search the Scriptures and my own heart."[2]

Like magic lantern shows and Lyceum lectures, chalk talks, with their presentation of images changing in real time, could be educational as well as entertaining.[5] They were choreographed performances "where the images would become animate, melding one into another in an orderly and progressive way" to tell a story.[6] Chalk talks began to be used for religious rallies[7] and became popular acts in vaudeville and at Chautuaqua assemblies.[8] Some performers, such as James Stuart Blackton, created acts around "lightning sketches," drawings which were rapidly modified as the audience looked on. "Tricks" or illustrative techniques used by performers were called "stunts."[9] The seemingly magical stunts, and the chalk talk artist's power to transform simple images before their audiences' eyes, appealed to magicians. Cartoonist and magician Harlan Tarbell performed as a chalk-talker and published several chalk talk method books.[10]

Winsor McCay began doing vaudeville chalk talks in 1906.[11] In his The Seven Ages of Man vaudeville act, he drew two infant faces, a boy and a girl, and progressively aged them.[12][13] Popular illustrator Vernon Grant was also known for his vaudeville circuit chalk talks. Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist John T. McCutcheon was a popular chalk talk performer.[9] Artist and suffragist Adele Goodman Clark set up her easel on a street corner to convince listeners to support woman suffrage.[14] Canadian cartoonist John Wilson Bengough toured internationally, giving chalk talks both for entertainment and in support of causes including woman suffrage and prohibition.[15]

Chalk talks contributed to the development of early animated films, such as The Enchanted Drawing by James Stuart Blackton and his partner, Alfred E. Smith.[13] Blackton's Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (1906) was another early animated film with its roots in chalk talks.[16] For his early films, Winsor McCay borrowed Blackton's image of the artist standing before drawings that come to life.[12]

| Authority control databases: National |

|

|---|