Achalk talk is an illustrated performance in which the speaker draws pictures to emphasize lecture points and create a memorable and entertaining experience for listeners. Chalk talks differ from other types of illustrated talks in their use of real-time illustration rather than static images. They achieved great popularity during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, appearing in vaudeville shows, Chautauqua assemblies, religious rallies, and smaller venues. Since their inception, chalk talks have been both a popular form of entertainment and a pedagogical tool.

One of the earliest chalk talk artists was a prohibition illustrator named Frank Beard (1842–1905).[1][2] Beard was a professional illustrator and editorial cartoonist who published in The Ram's Horn, an interdenominational social gospel magazine.[3] Beard's wife was a Methodist, and when the women of their church asked Beard to draw some pictures as part of an evening of entertainment they were planning, the chalk talk was born.[4] In 1896, Beard published Chalk Lessons; or, The Black-board in the Sunday School, which he dedicated to the Rev. Albert D. Vail "[t]hrough whose simple Black-board teaching I was first led to search the Scriptures and my own heart."[2]

Like magic lantern shows and Lyceum lectures, chalk talks, with their presentation of images changing in real time, could be educational as well as entertaining.[5] They were choreographed performances "where the images would become animate, melding one into another in an orderly and progressive way" to tell a story.[6] Chalk talks began to be used for religious rallies[7] and became popular acts in vaudeville and at Chautuaqua assemblies.[8] Some performers, such as James Stuart Blackton, created acts around "lightning sketches," drawings which were rapidly modified as the audience looked on. "Tricks" or illustrative techniques used by performers were called "stunts."[9] The seemingly magical stunts, and the chalk talk artist's power to transform simple images before their audiences' eyes, appealed to magicians. Cartoonist and magician Harlan Tarbell performed as a chalk-talker and published several chalk talk method books.[10]

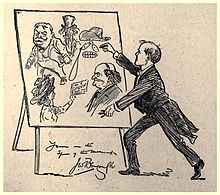

Winsor McCay began doing vaudeville chalk talks in 1906.[11] In his The Seven Ages of Man vaudeville act, he drew two infant faces, a boy and a girl, and progressively aged them.[12][13] Popular illustrator Vernon Grant was also known for his vaudeville circuit chalk talks. Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist John T. McCutcheon was a popular chalk talk performer.[9] Artist and suffragist Adele Goodman Clark set up her easel on a street corner to convince listeners to support woman suffrage.[14] Canadian cartoonist John Wilson Bengough toured internationally, giving chalk talks both for entertainment and in support of causes including woman suffrage and prohibition.[15]

Chalk talks contributed to the development of early animated films, such as The Enchanted Drawing by James Stuart Blackton and his partner, Alfred E. Smith.[13] Blackton's Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (1906) was another early animated film with its roots in chalk talks.[16] For his early films, Winsor McCay borrowed Blackton's image of the artist standing before drawings that come to life.[12]

| Authority control databases: National |

|

|---|