Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 256 BC–125 BC | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Balkh Ai-Khanoum | ||||||||

| Common languages | Greek Bactrian | ||||||||

| Religion | Greek gods Buddhism | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| King | |||||||||

• 250–240 BC | Diodotus I | ||||||||

• 145–130 BC | Heliocles I | ||||||||

| Historical era | Antiquity | ||||||||

• Established | 256 BC | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 125 BC | ||||||||

| |||||||||

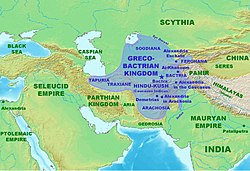

The Greco-Bactrian Kingdom was the easternmost part of the Hellenistic world, covering Bactria and SogdianainCentral Asia from 250 to 125 BC. The expansion of the Greco-Bactrians into northern India from 180 BC established the Indo-Greek Kingdom, which was to last until around 10 AD.

The Greco-Bactrian Kingdom was founded when Diodotus I, the satrap of Bactria (and probably the surrounding provinces) seceded from the Seleucid Empire around 250 BC. The preserved ancient sources (see below) are somewhat contradictory and the exact date of Bactrian independence has not been settled. Somewhat simplified, there is a high chronology (c. 255 BC) and a low chronology (c. 246 BC) for Diodotos’ secession.[1] The high chronology has the advantage of explaining why the Seleucid king Antiochus II issued very few coins in Bactria, as Diodotos would have become independent there early in Antiochus' reign.[2] On the other hand, the low chronology, from the mid-240s BC, has the advantage of connecting the secession of Diodotus I with the Third Syrian War, a catastrophic conflict for the Seleucid Empire.

The new kingdom, highly urbanized and considered as one of the richest of the Orient (opulentissimum illud mille urbium Bactrianum imperium "The extremely prosperous Bactrian empire of the thousand cities" Justin, XLI,1 [4]), was to further grow in power and engage into territorial expansion to the east and the west:

When the ruler of neighbouring Parthia, the former satrap and self-proclaimed king Andragoras, was eliminated by Arsaces, the rise of the Parthian Empire cut off the Greco-Bactrians from direct contact with the Greek world. Overland trade continued at a reduced rate, while sea trade between Greek Egypt and Bactria developed.

Diodotus was succeeded by his son Diodotus II, who allied himself with the Parthian Arsaces in his fight against Seleucus II:

Euthydemus, a Magnesian Greek according to Polybius[7] and possibly satrap of Sogdiana, overthrew Diodotus II around 230 BC and started his own dynasty. Euthydemus's control extended to Sogdiana, going beyond the city of Alexandria Eschate founded by Alexander the Great in Ferghana:

Euthydemus was attacked by the Seleucid ruler Antiochus III around 210 BC. Although he commanded 10,000 horsemen, Euthydemus initially lost a battle on the Arius [9] and had to retreat. He then successfully resisted a three-year siege in the fortified city of Bactra (modern Balkh), before Antiochus finally decided to recognize the new ruler, and to offer one of his daughters to Euthydemus's son Demetrius around 206 BC.[10] Classical accounts also relate that Euthydemus negotiated peace with Antiochus III by suggesting that he deserved credit for overthrowing the original rebel Diodotus, and that he was protecting Central Asia from nomadic invasions thanks to his defensive efforts:

Following the departure of the Seleucid army, the Bactrian kingdom seems to have expanded. In the west, areas in north-eastern Iran may have been absorbed, possibly as far as into Parthia, whose ruler had been defeated by Antiochus the Great. These territories possibly are identical with the Bactrian satrapies of Tapuria and Traxiane.

To the north, Euthydemus also ruled Sogdiana and Ferghana, and there are indications that from Alexandria Eschate the Greco-Bactrians may have led expeditions as far as Kashgar and ÜrümqiinChinese Turkestan, leading to the first known contacts between China and the West around 220 BC. The Greek historian Strabo too writes that:

Several statuettes and representations of Greek soldiers have been found north of the Tien Shan, on the doorstep to China, and are today on display in the Xinjiang museum at Urumqi (Boardman [11]).

Greek influences on Chinese art have also been suggested (Hirth, Rostovtzeff). Designs with rosette flowers, geometric lines, and glass inlays, suggestive of Hellenistic influences,[12] can be found on some early Han bronze mirrors, dated between 300–200 BC.[13]

Numismatics also suggest that some technology exchanges may have occurred on these occasions: the Greco-Bactrians were the first in the world to issue cupro-nickel (75/25 ratio) coins,[14] an alloy technology only known by the Chinese at the time under the name "White copper" (some weapons from the Warring States Period were in copper-nickel alloy [15]). The practice of exporting Chinese metals, in particular iron, for trade is attested around that period. Kings Agathocles and Pantaleon made these coin issues around 170 BC. Copper-nickel would not be used again in coinage until the 19th century.

The presence of Chinese people in India from ancient times is also suggested by the accounts of the "Ciñas" in the Mahabharata and the Manu Smriti.

The Han Dynasty explorer and ambassador Zhang Qian visited Bactria in 126 BC, and reported the presence of Chinese products in the Bactrian markets:

Upon his return, Zhang Qian informed the Chinese emperor Han Wudi of the level of sophistication of the urban civilizations of Ferghana, Bactria and Parthia, who became interested in developing commercial relationship them:

A number of Chinese envoys were then sent to Central Asia, triggering the development of the Silk Road from the end of the 2nd century BC.[16]

The Indian emperor Chandragupta, founder of the Mauryan dynasty, had re-conquered northwestern India upon the death of Alexander the Great around 322 BC. However, contacts were kept with his Greek neighbours in the Seleucid Empire, a dynastic alliance or the recognition of intermarriage between Greeks and Indians were established (described as an agreement on Epigamia in Ancient sources), and several Greeks, such as the historian Megasthenes, resided at the Mauryan court. Subsequently, each Mauryan emperor had a Greek ambassador at his court.

Chandragupta's grandson Asoka converted to the Buddhist faith and became a great proselytizer in the line of the traditional Pali canon of Theravada Buddhism, directing his efforts towards the Indian and the Hellenistic worlds from around 250 BC. According to the Edicts of Ashoka, set in stone, some of them written in Greek, he sent Buddhist emissaries to the Greek lands in Asia and as far as the Mediterranean. The edicts name each of the rulers of the Hellenistic world at the time.

Some of the Greek populations that had remained in northwestern India apparently converted to Buddhism:

Furthermore, according to Pali sources, some of Ashoka's emissaries were Greek Buddhist monks, indicating close religious exchanges between the two cultures:

Greco-Bactrians probably received these Buddhist emissaries (At least Maharakkhita, lit. "The Great Saved One", who was "sent to the country of the Yona") and somehow tolerated the Buddhist faith, although little proof remains. In the 2nd century AD, the Christian dogmatist Clement of Alexandria recognized the existence of Buddhist Sramanas among the Bactrians ("Bactrians" meaning "Oriental Greeks" in that period), and even their influence on Greek thought:

Demetrius, the son of Euthydemus, started an invasion of India from 180 BC, a few years after the Mauryan empire had been overthrown by the Sunga dynasty. Historians differ on the motivations behind the invasion. Some historians suggest that the invasion of India was intended to show their support for the Mauryan empire, and to protect the Buddhist faith from the religious persecutions of the Sungas as alleged by Buddhist scriptures (Tarn). Other historians have argued however that the accounts of these persecutions have been exaggerated (Thapar, Lamotte).

Demetrius may have been as far as the imperial capital Pataliputra in eastern India (today Patna). However, these campaigns are typically attributed to Menander. The invasion was completed by 175 BC. This established in northern India what is called the Indo-Greek Kingdom, which lasted for almost two centuries until around AD 10. The Buddhist faith flourished under the Indo-Greek kings, foremost among them Menander I. It was also a period of great cultural syncretism, exemplified by the development of Greco-Buddhism.

Back in Bactria, Eucratides, either a general of Demetrius or an ally of the Seleucids, managed to overthrow the Euthydemid dynasty and establish his own rule around 170 BC, probably dethroning Antimachus I and Antimachus II. The Indian branch of the Euthydemids tried to strike back. An Indian king called Demetrius (very likely Demetrius II) is said to have returned to Bactria with 60,000 men to oust the usurper, but he apparently was defeated and killed in the encounter:

Eucratides campaigned extensively in northwestern India, and ruled on a vast territory as indicated by his minting of coins in many Indian mints, possibly as far as the Jhelum RiverinPunjab. In the end however, he was repulsed by the Indo-Greek king Menander I, who managed to create a huge unified territory.

In a rather confused account, Justin explains that Eucratides was killed on the field by "his son and joint king", who would be his own son, either Eucratides IIorHeliocles I (although there are speculations that it could be his enemy's son Demetrius II). The son drove over Eucratides' bloodied body with his chariot and left him dismembered without a sepulchre:

Concurrently, and possibly during or after his Indian campaigns, Eucratides' Bactria was attacked and defeated by the Parthian king Mithridates I, possibly in alliance with partisans of the Euthydemids:

Following his victory, Mithridates I gained Bactria's territory west of the Arius, the regions of Tapuria and Traxiane:

In the year 141 BC, the Greco-Bactrians seem to have entered in an alliance with the Seleucid king Demetrius II to fight again against Parthia:

The 5th century historian Orosius declares that Mithridates I managed to occupy territory between the Indus and the Hydaspes towards the end of his reign, c. 138 BC, before his kingdom was weakened by his death in 136 BC.[20]

Heliocles I ended up ruling in what territory remained. The defeat, both in the west and the east, may have left Bactria very weakened and open to the nomadic invasions.

According to the Han chronicles, following a crushing defeat in 162 BC by the Xiongnu (Huns), the nomadic tribes of the Yuezhi fled from the Tarim Basin towards the west, crossed the neighbouring urban civilization of the "Ta-Yuan" (probably the Greek possessions in Ferghana), and resettled north of the Oxus in modern-day Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, in the northern part of the Greco-Bactrian territory. The Ta-Yuan remained a healthy and powerful urban civilization which had numerous contacts and exchanges with China from 130 BC.

The Yuezhi apparently occupied the Greco-Bactrian territory north of the Oxus during the reign of Eucratides, who was busy fighting in India against the Indo-Greeks.

Around 140 BC, eastern Scythians (the Saka, or Sacaraucae of Greek sources), apparently being pushed forward by the southward migration of the Yuezhi started to invade various parts of Parthia and Bactria. Their invasion of Parthia is well documented, in which they attacked in the direction of the cities of Merv, Hecatompolis and Ectabana. They managed to defeat and kill the Parthian king Phraates II, son of Mithridates I, routing the Greek mercenary troops under his command (troops he had acquired during his victory over Antiochus VII). Again in 123 BC, Phraates's successor, his uncle Artabanus I was killed by the Scythians.[21]

It seems that Bactria was also attacked and strongly diminished during the same massive movement of the Scythians. The destruction of the Greco-Bactrian city of Ai-Khanoum, dated to around 140 BC, is regularly attributed to them. The Scythians would be further displaced to the South and South-East into Afghanistan and India, under the pressure of the Yuezhi.

The culture of these nomadic invaders is apparently documented by such archaeological sites as Tillia Tepe, is northwestern Afghanistan.

When Zhang Qian visited the Yuezhi in 126 BC, trying to obtain their alliance to fight the Xiongnu, he explained that the Yuezhi were settled north of the Oxus but also held under their sway the territory south of Oxus, which makes up the remaining of Bactria.

According to Zhang Qian, the Yuezhi represented a considerable force of between 100,000 and 200,000 mounted archer warriors,[22] with customs identical to those of the Xiongnu, which would probably have easily defeated Greco-Bactrian forces (in 208 BC when the Greco-Bactrian king Euthydemus I confronted the invasion of the Seleucid king Antiochus III the Great, he commanded 10,000 horsemen [9]). Zhang Qian actually visited Bactria (named Daxia in Chinese) in 126 BC, and portrays a country which was totally demoralized and whose political system had vanished, although its urban infrastructure remained:

The Yuezhi further expanded southward into Bactria around 120 BC, apparently further pushed out by invasions from the northern Wu-Sun. It seems they also pushed Scythian tribes before them, which continued to India, where they came to be identified as Indo-Scythians.

The invasion is also described in western Classical sources from the 1st century BC, with different names than those used by the Chinese:

Around that time the king Heliocles abandoned Bactria and moved his capital to the Kabul valley, from where he ruled his Indian holdings. Having left the Bactrian territory, he is technically the last Greco-Bactrian king, although several of his descendants, moving beyond the Hindu Kush, would form the western part of the Indo-Greek kingdom. The last of these "western" Indo-Greek kings, Hermaeus, would rule until around 70 BC, when the Yuezhi again invaded his territory in the Paropamisadae (while the "eastern" Indo-Greek kings would continue to rule until around AD 10 in the area of the Punjab).

Overall, the Yuezhi remained in Bactria for more than a century. They became Hellenized to some degree, as suggested by their adoption of the Greek alphabet to write their Iranian language, and by numerous remaining coins, minted in the style of the Greco-Bactrian kings, with the text in Greek.

Around 12 BC the Yuezhi then moved further to northern India where they established the Kushan Empire.

Territories of Bactria, Sogdiana, Ferghana, Arachosia:

The existence of a third Diodotid king, Antiochus Nikator, is uncertain.

Many of the dates, territories, and relationships between Greco-Bactrian kings are tentative and essentially based on numismatic analysis and a few Classical sources. The following list of kings, dates and territories after the reign of Demetrius is derived from the latest and most extensive analysis on the subject, by Osmund Bopearachchi ("Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonné", 1991).

Territories of Bactria, Sogdiana, Ferghana, Arachosia:

The descendants of the Greco-Bactrian king Euthydemus invaded northern India around 190 BC. Their dynasty was probably thrown out of Bactria after 170 BC by the new king Eucratides, but remained in the Indian domains of the empire at least until the 150s BC.

The territory won by Demetrius was separated between western and eastern parts, ruled by several sub-kings and successor kings:

Territory of Bactria

Territories of Paropamisadae, Arachosia, Gandhara, Punjab

Territory of Bactria and Sogdiana

Heliocles, the last Greek king of Bactria, was invaded by the nomadic tribes of the Yuezhi from the North. Descendants of Eucratides may have ruled on in the Indo-Greek kingdom.

The Greco-Bactrians were known for their high level of Hellenistic sophistication, and kept regular contact with both the Mediterranean and neighbouring India. They were on friendly terms with India and exchanged ambassadors.

Their cities, such as Ai-Khanoum in northeastern Afghanistan (probably Alexandria on the Oxus), and Bactra (modern Balkh) where Hellenistic remains have been found, demonstrate a sophisticated Hellenistic urban culture. This site gives a snapshot of Greco-Bactrian culture around 145 BC, as the city was burnt to the ground around that date during nomadic invasions and never re-settled. Ai-Khanoum "has all the hallmarks of a Hellenistic city, with a Greek theater, gymnasium and some Greek houses with colonnaded courtyards" (Boardman). Remains of Classical Corinthian columns were found in excavations of the site, as well as various sculptural fragments. In particular a huge foot fragment in excellent Hellenistic style was recovered, which is estimated to have belonged to a 5–6 meters tall statue.

One of the inscriptions in Greek found at Ai-Khanoum, the Herôon of Kineas, has been dated to 300–250 BC, and describes Delphic precepts:

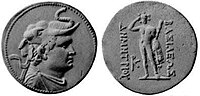

Some of the Greco-Bactrian coins, and those of their successors the Indo-Greeks, are considered the finest examples of Greek numismatic art with "a nice blend of realism and idealization", including the largest coins to be minted in the Hellenistic world: the largest gold coin was minted by Eucratides (reigned 171–145 BC), the largest silver coin by the Indo-Greek king Amyntas (reigned c. 95–90 BC). The portraits "show a degree of individuality never matched by the often bland depictions of their royal contemporaries further West" (Roger Ling, "Greece and the Hellenistic World").

Several other Greco-Bactrian cities have been further identified, as in Saksanokhur in southern Tajikistan (archaeological searches by a Soviet team under B.A. Litvinski), or in Dal'verzin Tepe.

|

Iran topics

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Hellenistic rulers

| |

|---|---|

| Argeads |

|

| Antipatrids |

|

| Antigonids |

|

| Ptolemies |

|

| Monarchs of Cyrene |

|

| Seleucids |

|

| Lysimachids |

|

| Attalids |

|

| Greco-Bactrians |

|

| Indo-Greeks |

|

| Monarchs of Bithynia |

|

| Monarchs of Pontus |

|

| Monarchs of Commagene |

|

| Monarchs of Cappadocia |

|

| Monarchs of the Cimmerian Bosporus |

|

| Monarchs of Epirus |

|

Hellenistic rulers were preceded by Hellenistic satraps in most of their territories. | |