|

|

#article-section-source-editor

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app edit

|

||

| (44 intermediate revisions by 18 users not shown) | |||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

{{EngvarB|date=May 2015}} |

{{EngvarB|date=May 2015}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=May 2015}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=May 2015}} |

||

{{More citations needed|date=January 2024}} |

|||

{{Infobox officeholder |

{{Infobox officeholder |

||

| honorific-prefix = [[The Right Honourable]] |

| honorific-prefix = [[The Right Honourable]] |

||

| name = The Earl of Liverpool |

| name = The Earl of Liverpool |

||

| honorific-suffix = {{post-nominals|country=GBR|size=100%|KG|PC|FRS}} |

| honorific-suffix = {{post-nominals|country=GBR|size=100%|KG|PC|FRS}} |

||

| image = File:Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool.jpg |

| image = File:Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769-1830) - Robert Banks Jenkinson (1770-1828), 2nd Earl of Liverpool - RCIN 404930 - Royal Collection.jpg |

||

| alt = Oil painting by Thomas Lawrence |

| alt = Oil painting by Thomas Lawrence |

||

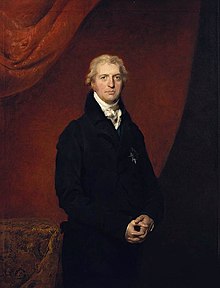

| caption = Portrait by [[Thomas Lawrence]], {{circa| |

| caption = ''[[Portrait of Lord Liverpool]]'' by [[Thomas Lawrence]], {{circa|1820}} |

||

| office = [[Prime Minister of the United Kingdom]] |

| office = [[Prime Minister of the United Kingdom]] |

||

| term_start = 8 June 1812 |

| term_start = 8 June 1812 |

||

| Line 53: | Line 54: | ||

| predecessor6 = [[Charles Philip Yorke]] |

| predecessor6 = [[Charles Philip Yorke]] |

||

| successor6 = The Earl Spencer |

| successor6 = The Earl Spencer |

||

| office7 = [[ |

| office7 = [[Foreign Secretary]] |

||

| term_start7 = 20 February 1801 |

| term_start7 = 20 February 1801 |

||

| term_end7 = 14 May 1804 |

| term_end7 = 14 May 1804 |

||

| Line 61: | Line 62: | ||

| birth_name = Robert Banks Jenkinson |

| birth_name = Robert Banks Jenkinson |

||

| birth_date = {{Birth date|df=yes|1770|6|7}} |

| birth_date = {{Birth date|df=yes|1770|6|7}} |

||

| birth_place = London, England |

| birth_place = [[London]], England |

||

| death_date = {{Death date and age|df=yes|1828|12|4|1770|6|7}} |

| death_date = {{Death date and age|df=yes|1828|12|4|1770|6|7}} |

||

| death_place = [[Kingston upon Thames]], Surrey, England |

| death_place = [[Kingston upon Thames]], [[Surrey]], England |

||

| resting_place = Hawkesbury Parish Church, [[Gloucestershire]], England |

| resting_place = [[Church of St Mary, Hawkesbury|Hawkesbury Parish Church]], [[Gloucestershire]], England |

||

| parents = [[Charles Jenkinson, 1st Earl of Liverpool|Charles Jenkinson]] (father) |

| parents = [[Charles Jenkinson, 1st Earl of Liverpool|Charles Jenkinson]] (father) |

||

| spouse = {{plainlist}} |

| spouse = {{plainlist}} |

||

* {{marriage|[[Louisa Jenkinson, Countess of Liverpool|Louisa Hervey]]|25 March 1795|12 June 1821|reason=d}} |

* {{marriage|[[Louisa Jenkinson, Countess of Liverpool|Louisa Hervey]]|25 March 1795|12 June 1821|reason=d}} |

||

* {{marriage|[[Mary Jenkinson, Countess of Liverpool|Mary Chester]]<br>|24 September 1822}} |

* {{marriage|[[Mary Jenkinson, Countess of Liverpool|Mary Chester]]<br/>|24 September 1822}} |

||

{{endplainlist}} |

{{endplainlist}} |

||

| education = [[Charterhouse School]] |

| education = [[Charterhouse School]] |

||

| Line 79: | Line 80: | ||

'''Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool''', {{post-nominals|country=GBR|commas=true|size=100%|KG|PC|FRS}} (7 June 1770 – 4 December 1828) was a [[British Tory]] statesman who served as [[Prime Minister of the United Kingdom]] from 1812 to 1827. He also held many other important cabinet offices such as [[Foreign Secretary]], [[Home Secretary]] and [[Secretary of State for War and the Colonies]]. He was also a member of the [[House of Lords]] and served as [[Leader of the House of Lords|leader]]. |

'''Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool''', {{post-nominals|country=GBR|commas=true|size=100%|KG|PC|FRS}} (7 June 1770 – 4 December 1828) was a [[British Tory]] statesman who served as [[Prime Minister of the United Kingdom]] from 1812 to 1827. He also held many other important cabinet offices such as [[Foreign Secretary]], [[Home Secretary]] and [[Secretary of State for War and the Colonies]]. He was also a member of the [[House of Lords]] and served as [[Leader of the House of Lords|leader]]. |

||

As prime minister, |

As prime minister, Jenkinson called for repressive measures at domestic level to maintain order after the [[Peterloo Massacre]] of 1819. He dealt smoothly with [[the Prince Regent]] when [[King George III]] was incapacitated. He also steered the country through the period of [[Classical radicalism|radicalism]] and unrest that followed the [[Napoleonic Wars]]. He favoured commercial and manufacturing interests as well as the landed interest. He sought a compromise of the heated issue of [[Catholic emancipation]]. The revival of the economy strengthened his political position. By the 1820s, he was the leader of a reform faction of "Liberal Tories" who lowered the tariff, abolished the [[death penalty]] for many offences, and reformed the [[criminal law]]. By the time of his death, however, the [[Tories (British political party)|Tory party]], which had dominated the House of Commons for over 40 years, was ripping itself apart. |

||

Important events during his tenure as prime minister included the [[War of 1812]] with the United States, the [[War of the Sixth Coalition|Sixth]] and [[Hundred Days|Seventh Coalitions]] against the [[First French Empire|French Empire]], the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars at the [[Congress of Vienna]], the [[Corn Laws]], the Peterloo Massacre, the [[Doctrine of the Trinity Act 1813|Trinitarian Act 1812]] and the emerging issue of Catholic emancipation. |

Important events during his tenure as prime minister included the [[War of 1812]] with the United States, the [[War of the Sixth Coalition|Sixth]] and [[Hundred Days|Seventh Coalitions]] against the [[First French Empire|French Empire]], the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars at the [[Congress of Vienna]], the [[Corn Laws]], the [[Peterloo Massacre]] against pro-[[democracy]] protestors, the [[Doctrine of the Trinity Act 1813|Trinitarian Act 1812]] and the emerging issue of Catholic emancipation. Despite being called "the Arch-mediocrity" by a later [[Conservative Party (UK)|Conservative]] prime minister, [[Benjamin Disraeli]], scholars rank him highly among all British prime ministers.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Paul Strangio|author2=Paul 't Hart|author3=James Walter|title=Understanding Prime-Ministerial Performance: Comparative Perspectives|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kMu2nAZmMbEC&pg=PA225|year=2013|publisher=Oxford UP|page=225|isbn=978-0-19-966642-3}}</ref> |

||

==Early life |

==Early life== |

||

Jenkinson was baptised on 29 June 1770 at [[St. Margaret's, Westminster]], the son of [[George III of the United Kingdom|George III]]'s close adviser [[Charles Jenkinson, 1st Earl of Liverpool|Charles Jenkinson]], later the first [[Earl of Liverpool]], and his first wife, Amelia Watts. Jenkinson's 19-year-old mother, who was the daughter of a senior [[East India Company]] official, [[William Watts (East India Company official)|William Watts]], and of his wife [[Begum Johnson]], died from the [[Maternal death|effects of childbirth]] one month after his birth.<ref name="Nineteenth-Century British Premiers p. 82">D. Leonard 2008 ''Nineteenth-Century British Premiers: Pitt to Rosebery''. Palgrave Macmillan: p. 82.</ref> Through his mother's grandmother, Isabella Beizor, Jenkinson was descended from Portuguese settlers in India; he may also have been one-sixteenth [[Indian people|Indian]] in ancestry.<ref>{{cite magazine |url=https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v06/n19/robert-blake/weathering-the-storm |title=Weathering the storm |first=Robert |last=Blake |magazine=London Review of Books |volume=6 |issue=19 |date=October 18, 1984 |access-date=25 March 2020}}</ref><ref>"Edward Croke's wife, Isabella Beizor (c. 1710–80), was a Portuguese Indian creole, thus giving Liverpool a trace (probably about one sixteenth, but maybe less) of Indian blood." Hutchinson, Martin, ''Britain's Greatest Prime Minister: Lord Liverpool''</ref><ref>"It is true that [Lord Liverpool's] maternal grandmother was a Calcutta-born woman, Frances Croke ... there is no evidence that her half-Portuguese mother, Isabella Beizor, was Eurasian." Brendon, de Vyvyen, ''Children of the Raj''</ref> |

|||

=== Family === |

|||

Jenkinson was baptised on 29 June 1770 at [[St. Margaret's, Westminster]], the son of [[George III of the United Kingdom|George III]]'s close adviser [[Charles Jenkinson, 1st Earl of Liverpool|Charles Jenkinson]], later the first [[Earl of Liverpool]], and his first wife, Amelia Watts. Jenkinson's 19-year-old mother, who was the daughter of a senior [[East India Company]] official, [[William Watts (East India Company official)|William Watts]], and of his wife [[Begum Johnson]], died from the [[Maternal death|effects of childbirth]] one month after his birth.<ref name="Nineteenth-Century British Premiers p. 82">D. Leonard 2008 ''Nineteenth-Century British Premiers: Pitt to Rosebery''. Palgrave Macmillan: p. 82.</ref> Through his mother's grandmother, Isabella Beizor, Jenkinson was descended from Portuguese settlers in India; he may also have been one-sixteenth Indian in ancestry.<ref>{{cite magazine |url=https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v06/n19/robert-blake/weathering-the-storm |title=Weathering the storm |first=Robert |last=Blake |magazine=London Review of Books |volume=6 |issue=19 |date=October 18, 1984 |access-date=25 March 2020}}</ref><ref>"Edward Croke's wife, Isabella Beizor (c. 1710–80), was a Portuguese Indian creole, thus giving Liverpool a trace (probably about one sixteenth, but maybe less) of Indian blood." Hutchinson, Martin, ''Britain's Greatest Prime Minister: Lord Liverpool''</ref><ref>"It is true that [Lord Liverpool's] maternal grandmother was a Calcutta-born woman, Frances Croke ... there is no evidence that her half-Portuguese mother, Isabella Beizor, was Eurasian." Brendon, de Vyvyen, ''Children of the Raj''</ref> |

|||

Jenkinson was educated at [[Charterhouse School]] and matriculated at [[Christ Church, Oxford]], in 1787.{{sfn|Chisholm|1911}}<ref>{{alox2|title=Jenkinson, Robert Bankes}}</ref> In the summer of 1789, Jenkinson spent four months in Paris to perfect his French and enlarge his social experience. He returned to Oxford for three months to complete his terms of residence, and in May 1790 was created Master of Arts. |

|||

=== Education === |

|||

From an early age, Jenkinson had a strong influential training in economics and politics from his father, who was at the time, a leading politician and adviser to [[George III of the United Kingdom|King George III]].<ref name="cato.org">https://www.cato.org/cato-journal/fall-2021/economic-policies-lord-liverpool#</ref> To give his son the highest education possible, Jenkinson was sent to be educated at [[Charterhouse School]], whose education was broader than that of the prestigious [[Eton College]], to which many sons of noblemen were sent be educated.<ref name="cato.org"/> While at Charterhouse, Jenkinson's father insisted that he study political economy and read current politics. Jenkinson later matriculated at [[Christ Church, Oxford]], in 1787.{{sfn|Chisholm|1911}}<ref name="ReferenceA">{{alox2|title=Jenkinson, Robert Bankes}}</ref> |

|||

|

|||

[[Image:2nd Earl of Liverpool 1790s.jpg|thumb|left|upright|Jenkinson by [[Thomas Lawrence|Lawrence]], 1790s]] While learning at Oxford, he went on the tradition "[[Grand Tour]]" of Europe, which was undertaken by most wealthy students to travel abroad.<ref name="cato.org"/> In the summer of 1789, he took his Grand Tour, first travelling to Italy and then to Paris, France.<ref name="cato.org"/> In Paris, Jenkinson spent four months there to perfect his French and enlarge his social experience among Parisian Society.<ref>https://victorianweb.org/history/Liverpool.html</ref> While there, he witnessed the [[storming of the Bastille]] during the early stages of the [[French Revolution]] and before the revolution took place, he was able to safely return to England and in time for his last year at Oxford.<ref name="cato.org"/> He spent next the three months in Oxford to complete his terms of residence, and in May 1790 was created Master of Arts. |

|||

[[Image:2nd Earl of Liverpool 1790s.jpg|thumb|left|upright|''[[Portrait of Lord Hawkesbury]]'' by [[Thomas Lawrence|Lawrence]], 1796]] |

|||

== Early career: 1790–1801== |

|||

== Early career (1790–1812)== |

|||

=== Member of Parliament === |

=== Member of Parliament === |

||

He won election to the [[British House of Commons|House of Commons]] in 1790 for [[Rye (UK Parliament constituency)|Rye]], a seat he would hold until 1803; at the time, however, he was below the age of assent to Parliament, so he refrained from taking his seat and spent the following winter and early spring in an extended tour of |

He won election to the [[British House of Commons|House of Commons]] in 1790 for [[Rye (UK Parliament constituency)|Rye]], a seat he would hold until 1803; at the time, however, he was below the age of assent to Parliament, so he refrained from taking his seat and spent the following winter and early spring in an extended tour of [[Continental Europe]]. This tour took in the Netherlands and Italy; at its conclusion he was old enough to take his seat in Parliament. It is not clear exactly when he entered the Commons, but as his twenty-first birthday was not reached until almost the end of the 1791 session, it is possible that he waited until the following year. |

||

===House of Commons=== |

===House of Commons=== |

||

With the help of his father's influence and his political talent, he rose relatively |

With the help of his father's influence, and his political talent, he rose relatively quickly in the Tory government. In February 1792 he gave the reply to [[Samuel Whitbread (1764–1815)|Samuel Whitbread]]'s critical motion on the government's Russian policy. He delivered several other speeches during the session and was a strong opposer of abolitionism and [[William Wilberforce]]. He served as a member of the Board of Control for India from 1793 to 1796. |

||

In the defence movement that followed the outbreak of hostilities with France, Jenkinson |

In the defence movement that followed the outbreak of hostilities with France, Jenkinson was one of the first of the ministers of the government to enlist in the militia. He became a [[Colonel (United Kingdom)|colonel]] in the [[Cinque Ports Fencibles]] in 1794, his military duties leading to frequent absences from the Commons. His regiment was sent to Scotland in 1796 and he was quartered for a time in [[Dumfries]]. |

||

In 1797 |

In 1797 the then Lord Hawkesbury was the cavalry commander of the Cinque Ports Light Dragoons who ran amok following a protest against the [[Militia Act 1797|Militia Act]] at [[Tranent]] in [[East Lothian]], twelve civilians being killed. Author James Miller wrote in 1844 that "His lordship was blamed for remaining at [[Haddington, East Lothian|Haddington]], as his presence might have prevented the outrages of the soldiery."<ref>{{cite book |chapter-url=http://www.scottishmining.co.uk/506.html|last=Miller |first=James |date=1844 |title=The Lamp of Lothian, or, The history of Haddington: in connection with the public affairs of East Lothian and of Scotland, from the earliest records to the present period|chapter=Dreadful Riot and Military Massacre at Tranent, on the First Balloting for the Scots Militia for the County of Haddington |location=Haddington |publisher=James Allan |via=Scottish Mining}}</ref> |

||

His parliamentary attendance also suffered from his reaction when his father angrily opposed his projected marriage with [[Louisa Jenkinson, Countess of Liverpool|Lady Louisa Hervey]], daughter of the [[Frederick Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol|Earl of Bristol]]. After Pitt and the King had intervened on his behalf |

His parliamentary attendance also suffered from his reaction when his father angrily opposed his projected marriage with [[Louisa Jenkinson, Countess of Liverpool|Lady Louisa Hervey]], daughter of the [[Frederick Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol|Earl of Bristol]]. After Pitt and the King had intervened on his behalf the wedding finally took place at [[Wimbledon, London|Wimbledon]] on 25 March 1795. In May 1796, when his father was created Earl of Liverpool, he took the courtesy title of '''Lord Hawkesbury''' and remained in the Commons. He became '''Baron Hawkesbury''' in his own right and was elevated to the House of Lords in November 1803 in recognition for his work as Foreign Secretary.{{citation needed|date=May 2019}} He also served as [[Master of the Mint]] (1799–1801).{{sfn|Chisholm|1911}} |

||

===Cabinet=== |

|||

== Foreign Secretary: 1801–1804 == |

|||

=== |

==== Foreign Secretary ==== |

||

In [[Henry Addington]]'s government, he entered the cabinet in 1801 as [[Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (UK)|Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs]], in which capacity he negotiated the [[Treaty of Amiens]] with France.<ref name="autogenerated3">{{cite web |url=http://www.victorianweb.org/history/pms/Liverpool.html |title=Lord Liverpool |publisher=Victorian Web |date=4 March 2002}}</ref> Most of his time as Foreign Secretary was spent dealing with the nations of France and the United States. He continued to serve in the cabinet as [[Home Secretary]] in [[William Pitt the Younger|Pitt the Younger]]'s second government. While Pitt was seriously ill, Liverpool was in charge of the cabinet and drew up the King's Speech for the official opening of Parliament. When William Pitt died in 1806, the King asked Liverpool to accept the post of Prime Minister, but he refused, as he believed he lacked a governing majority. He was then made leader of the Opposition during [[Lord Grenville]]'s ministry (the only time that Liverpool did not hold government office between 1793 and after his retirement). In 1807, he resumed office as [[Home Secretary]] in [[William Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland|the Duke of Portland]]'s ministry.{{sfn|Chisholm|1911}} |

|||

As the question of [[Catholic emancipation]] came apparent and as [[George III of the United Kingdom|the King]] refused to pass on to law, in response, Pitt resigned as prime minister as a result. This departure left the King to choose a successor and so appointed one of Pitt's prominent allies, [[Henry Addington]], as the new prime minister. When Addington's government came to power, the young Liverpool entered the cabinet in 1801 as [[Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (UK)|Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs]].{{sfn|Chisholm|1911}} Addington's main political agenda was peace and promised that as prime minister that, he will negotiate with the French. In this capacity he was entrusted by Addington negotiate with the France and pursue an immediate peace deal, which he set to do, as his first duty.<ref name="autogenerated3">{{cite web |url=http://www.victorianweb.org/history/pms/Liverpool.html |title=Lord Liverpool |publisher=Victorian Web |date=4 March 2002}}</ref> |

|||

=== |

====War Secretary==== |

||

Lord Liverpool (as he had now become by the death of his father in December 1808) accepted the position of [[Secretary of State for War and the Colonies]] in [[Spencer Perceval]]'s government in 1809. Liverpool's first step on taking up his new post was to elicit from General [[Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington|Arthur Wellesley]] (the future Duke of Wellington) a strong enough statement of his ability to resist a French attack to persuade the cabinet to commit themselves to the maintenance of his small force in [[Portugal]]. In 1810 Liverpool was made a colonel of militia.<ref>[https://www.histparl.ac.uk/volume/1790-1820/member/jenkinson-hon-robert-banks-1770-1828 JENKINSON, Hon. Robert Banks (1770–1828), of Coombe Wood, nr. Kingston, Surr. {{!}} History of Parliament Online] "The History of Parliament" article by R. G. Thorne</ref> |

|||

The [[French Revolutionary Wars]] begun as a direct result of the [[French Revolution]], of which the aftermath saw a growing sentiment of [[Liberalism and radicalism in France|radicalism]] and a shock wave of political turmoil being sent across Europe. At the beginning of the Revolution, the British government led by [[William Pitt the Younger|William Pitt]] opposed its ideology and the belief that it would undermine the principles of Britain's established [[constitutional monarchy]]. Also the French revolutionary ideology heavily opposed such forms of government containing a monarchy, while favouring a [[republic|republican form]] of government, which Britain and other countries in Europe opposed and wished to end such ideologies from spreading elsewhere. What followed was a decade long series of wars, known as the [[Wars of the Coalition|Coalition wars]] that resulted in Britain and its allies being defeated or being pushed to the position of economic crisis and so many opted to peace.<ref name="historic-uk.com">https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Lord-Liverpool/</ref> |

|||

|

|||

As Foreign Secretary, Liverpool has to face the crisis war in Europe and negotiate peace as soon as possible. As Britain and its allies in the continent were unable to defeat France in any way and the long duration of the war itself, led to a period of instability as the British war effort has been over overwhelmed by nearly a decade of war without any results. As per Addington's wishes, Liverpool opened negotiations with France. Liverpool immediately, first, communicated with the French commissary for [[prisoners of war]] in London, [[Louis Guillaume Otto]], through whom he could contact and agree to [[Napoleon Bonaparte]]'s earlier proposals.<ref name="historic-uk.com"/> |

|||

Liverpool stated that he "wanted to open discussions on terms for a peace agreement", but Otto, who was under direct and strict orders from Bonaparte, begun to open negotiations by mid-September. Despite his efforts, negotiations seemed fruitless with Otto and unhappy with this result, Liverpool sent diplomat [[Anthony Merry]] to Paris to open a second round of negotiations with his own French counterpart, French [[Foreign Minister]] [[Talleyrand]] by mid-September. By this time, written negotiations followed and progressed to the point Otto met shaft a preliminary agreement on 30 September and finally in London, which was finally published the next day. Thus signing the [[Treaty of Amiens]] and concluding the end of the [[War of the Second Coalition]].<ref name="historic-uk.com"/> |

|||

=== Resignation === |

|||

Most of his time as Foreign Secretary was spent dealing with the nations of France and the United States. But this was cut short, as shortly afterwards, the Addington government came under attack from the opposition and was criticised for its lack of credibility when war resumed yet again in 1803 and the start of the [[War of the Third Coalition]]. Soon the government fell into disarray and quickly led to the reappointment of Pitt as prime minister.<ref name="historic-uk.com"/> |

|||

== Home Secretary: 1804–1809== |

|||

=== Pitt Ministry === |

|||

When Pitt came to power for the second time, he reappointed the former Foreign secretary and he was soon continued to serve in the cabinet as [[Home Secretary|Secretary of State for the Home Departmet]] in [[William Pitt the Younger|Pitt the Younger]]'s second government. Although the new government was smaller than the previous one, the ministry still held the support of both the King, Parliament and the public, whom still had high confidence installed in Pitt and it became the government's greatest strength. |

|||

Soon after taking the role of Prime Minister, Pitt fell ill and was sick during 1805. Despite a terminal illness, he managed the out-going war in Europe and was able to hold together his Cabinet and his country against the will-power of the French. While Pitt was seriously ill, Liverpool was in charge of the cabinet and drew up the [[Speech from the Throne|King's Speech]] for the official [[State Opening of Parliament]]. When William Pitt died in 1806, the King needed choose a successor to office immediately and asked the Home Secretary Liverpool to accept the post of Prime Minister, but he refused, as he believed he lacked a governing majority.{{sfn|Chisholm|1911}} |

|||

=== Opposition and return === |

|||

The death of Pitt, almost led to political unrest and the King soon appointed the former prime minister's cousin, [[William Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville]], as the new prime minister. Grenville lacked a strong majority in Parliament and had to call on every MP willing to join his new government, which led to the formation of a national unity government. The [[Ministry of All The Talents]] was formed by Grenville's aim to form the strongest possible coalition to avoid major opposition and included many leading politicians at the time. But Hawkesbury and Pitt's loyal supporters refused, who eventually left the government. |

|||

He then became [[Leader of the Opposition (UK)|Leader of the Opposition]] during [[William Grenville, 1st Baron Grenville|Lord Grenville]]'s ministry. This was the second only time that Liverpool did not hold active government office between 1793 and after his retirement. In 1807, after a year of Grenville's ministry in power, it fell without accomplishing any major policy efforts during its time. Hawkesbury, who was in opposition at the time, returned to government and he resumed office as [[Home Secretary]] in [[William Cavendish-Bentinck, 3rd Duke of Portland|the Duke of Portland]]'s new ministry.{{sfn|Chisholm|1911}} |

|||

==War Secretary: 1809–1812== |

|||

Lord Hawkesbury, by this point, assumed the title of Lord Liverpool, as he had now become by the death of his father in December 1808. After the fall of the [[Whigs (British political party)|Whig]] [[Second Portland ministry|Portland ministry]], saw the sudden rise of [[Spencer Perceval]] to the office of prime minister. Perceval was reluctant appoint a fellow Tory to his cabinet, as the Whigs were splintered and unified, which would allow the Tories to govern opposed and asked Liverpool to join his new cabinet. Liverpool accepted the position of [[Secretary of State for War and the Colonies]] in Perceval's [[Perceval ministry|new government]] in 1809. Liverpool's first step on taking up his new post was to elicit from General [[Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington|Arthur Wellesley]] (the future Duke of Wellington) a strong enough statement of his ability to resist a French attack to persuade the cabinet to commit themselves to the maintenance of his small force in [[Portugal]]. In 1810 Liverpool was made a colonel of militia.<ref>[https://www.histparl.ac.uk/volume/1790-1820/member/jenkinson-hon-robert-banks-1770-1828 JENKINSON, Hon. Robert Banks (1770–1828), of Coombe Wood, nr. Kingston, Surr. {{!}} History of Parliament Online] "The History of Parliament" article by R. G. Thorne</ref> |

|||

=== War finance === |

|||

By 1809 the political situation in Europe have changed dramatically. Napoleon has conquered most, if not almost, all of Europe except for Russia, Austria, Eastern Europe and Northern Europe. The war against [[Napoleonic France]] did not improve for Britain's war effort and is by this point, [[French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars|Five coalitions]] have failed to defeat Napoleon or bring down France. This did not help Britain overcome the [[Continental System]], issued by the 1806 [[Berlin Decree]], which forbade most countries of Europe from Engaging in trade and commerce with the British and prevented them from trading British goods. |

|||

This not only effected Britain, but affected all European countries as they were dependent on British supplies, mainly many of Britain's closest allies. This caused massive disruption in the trading and economic system of Europe, as they were at this point, were key trading partners of each other and likely led to an unstable economic crisis. But to prevent Britain falling to an economic crisis, Liverpool as War Secretary has raised loans to help the Britain win the war and also help Britain's allies in need. |

|||

At home, with a combination of strong government finances and sustain financial attrition was able to save Britain from falling behind the economic fallout. And by using the [[Royal Navy]] to undermine French naval activities, a blockade across the [[English Channel]] and with persistent but moderate military pressure on France would ultimately bear fruit and will win the war.<ref name="historic-uk.com"/> |

|||

==Prime Minister: 1812–1827<span class="anchor" id="Premiership"></span><!-- linked from redirects [[Premiership of Lord Liverpool]], [[Premiership of Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool]], [[Premiership of the Earl of Liverpool]], [[Prime ministership of Lord Liverpool]], {{subst:Delink|[[Prime ministership of the Earl of Liverpool]]}} --> == |

|||

{{see also|Prime ministership of the Earl of Liverpool}} |

|||

==Prime minister<span class="anchor" id="Premiership"></span><!-- linked from redirects [[Premiership of Lord Liverpool]], [[Premiership of Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool]], [[Premiership of the Earl of Liverpool]], [[Prime ministership of Lord Liverpool]], [[Prime ministership of the Earl of Liverpool]] --> (1812–1827)== |

|||

=== Appointment === |

=== Appointment === |

||

{{Further|Liverpool ministry}} |

{{Further|Liverpool ministry}} |

||

|

After the [[Assassination of Spencer Perceval]] in May 1812, [[George IV of the United Kingdom|George, the Prince Regent]], successively tried to appoint four men to succeed Perceval, but failed. Jenkinson, the [[Prince regent#Prince regent in the United Kingdom|Prince Regent]]'s fifth choice for the post, reluctantly accepted office on 8 June 1812.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.victorianweb.org/history/pms/Liverpool.html |title=Lord Liverpool |publisher=The Victorian Web |date=4 March 2002 |author=Marjie Bloy}}</ref>{{sfn|Chisholm|1911}} Jenkinson was proposed as successor by the cabinet office and [[Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh]] who acted as leader in the House of Commons. The Prince Regent, however, found it impossible to form a different coalition to advance an alternative candidate and confirmed Jenkinson as prime minister on 8 June. |

||

===The Liverpool government=== |

|||

===Government=== |

|||

Liverpool's government included some of the future leaders of Britain, such as Lord Castlereagh, [[George Canning]], the [[Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington|Duke of Wellington]], [[Robert Peel]], and [[William Huskisson]]. Liverpool was considered an experienced and skilled politician, and held together the liberal and reactionary wings of the Tory party, which his successors, Canning, [[F. J. Robinson, 1st Viscount Goderich|Goderich]] and Wellington, had great difficulty with. |

|||

Liverpool appointed many capable politicians into his new cabinet, most of whom held many positions within past government and had considerable experience, which he was most keen on. To avoid schisms and splits in his party, Liverpool appointed, not only his supporters and other [[Member of Parliament|MPs]] from reactionary or radical factions to form a strong government with a successful hand in passing major policies and reform. |

|||

===War=== |

|||

Liverpool's newly appointed government included some of the future great leaders of Britain, such as [[Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry|Lord Castlereagh]] as [[Foreign Secretary]], [[George Canning]] as [[Leader of the House of Commons]], former Prime Minister Addington as [[Home Secretary]], [[Nicholas Vansittart, 1st Baron Bexley|Nicholas Vansittart]] as [[Chancellor of the Exchequer]], the [[Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington|Duke of Wellington]], [[Robert Peel]], and [[William Huskisson]] as [[President of the Board of Trade]]. Liverpool was considered an experienced as well as skilled politician, and was highly successful in holding together the liberal and reactionary wings of the Tory party. This success would lead to a stable government which would remain in power for the next 14 years. |

|||

==== Congress of Vienna ==== |

|||

[[File:Congress of Vienna.PNG|thumb|left|''The Congress of Vienna'' by [[Jean-Baptiste Isabey]], 1819]] |

|||

===Foreign affairs=== |

|||

Liverpool's ministry was a long and eventful one. At the beginning of his premiership, Liverpool was faced directly with conflict, the [[War of 1812]] with the United States and the final campaigns of the Napoleonic Wars were fought during Liverpool's governance. It was during his ministry that the Peninsular Campaigns were fought, where the British army led by the [[Duke of Wellington]] drove the French out of [[Spain]] and [[Portugal]] that lasted six years. France was utterly defeated in the Napoleonic Wars, and Liverpool was appointed to the [[Order of the Garter]] that same year. At the peace negotiations that followed, Liverpool's main concern was to obtain a European settlement that would ensure the independence of the [[Netherlands]], Spain and [[Portugal]], and confine France inside its pre-war frontiers without damaging its national integrity. To achieve this, he was ready to return all British colonial conquests. Within this broad framework, he gave [[Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh|Castlereagh]] a discretion at the [[Congress of Vienna]], the next most important event of his ministry. At the congress, he gave prompt approval for Castlereagh's bold initiative in making the defensive alliance with [[Austria]] and France in January 1815. In the aftermath of the defeat of Napoleon – who had briefly been exiled to the island [[Elba]], but had [[Hundred Days|escaped exile and returned to rule France]]. The allies immediately began mobilising their armies to fight the escaped emperor and a combined Anglo-Allied army was sent under the command of Wellington to assist Britain's allies. Within a few months, Napoleon was decisively defeated at [[Battle of Waterloo|Waterloo]] in June that year, after many years of war, peace followed through the now exhausted continent. |

|||

==== War ==== |

|||

[[File:Waterloo Campaign map-alt3.svg|thumb|right|Map of the '''Waterloo''' campaign]] |

|||

[[File:BritishEmpire1815.png|thumb|The [[British Empire]] at the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815]] |

[[File:BritishEmpire1815.png|thumb|The [[British Empire]] at the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815]] |

||

At the beginning of his premiership, Liverpool had to face the [[Napoleonic Wars|outgoing conflict]] in [[Europe]]. [[First French Empire|The French Emperor]] [[Napoleon Bonaparte]] conquered nearly half of Europe and another half was under his rule and at this point, his hegemony over the continent seemed unshakable. Britain led the war solely on its own since 1809 and the although it helped to fund the escalating [[Peninsular War|war in Spain]] by sending [[British Army|British troops]] under the [[Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington|Duke of Wellington]] to defeat French forces there. When he became prime minister, Liverpool was determined to direct his new government on the goal to win the [[Napoleonic Wars|war against Napoleonic France]]. |

|||

During his first year in office, Napoleon's army led [[French invasion of Russia|an ill-fated invasion of Russia]] in a doomed attempt to subdue the [[Russian Empire]] into his sphere of control. But Napoleon suffered a devastating setback during the campaign and the loss of an army of around one and half million men, forcing him to retreat. To topple Napoleon, once and for all, [[War of the Sixth Coalition|a new Coalition]] was launched by the allies against [[Napoleon]] in 1813 and resulted in an effortless campaign on [[Rhine]] and the German frontier lasting a year, which eventually led to Napoleon's final defeat during the [[Hundred Days]] campaign in 1815.<ref>{{cite book | author1=Paul Brighton |title=Original Spin: Downing Street and the Press in Victorian Britain |publisher= Bloomsbury Publishing |year=2015 |page=35 |isbn=9780857728142 }}</ref> The [[War of 1812]] with the United States was fought during his government as well. |

|||

The Peninsular Campaigns saw the British army led by the [[Duke of Wellington]] drive the French out of Spain and [[Portugal]] into France itself. Also, the [[War of the Sixth Coalition|Sixth Coalition]] led by [[Russia]], [[Prussia]], [[Austria]] and [[Sweden]] successfully embarked on a [[German campaign of 1813|major campaign on the German front]] that resulted in Napoleon's crushing defeat at the [[Battle of Leipzig]]. With Napoleon's defeat, the Allies invaded France and occupied the capital, [[Paris]]. The fall of Paris led to Napoleon's abdication and exile to the island of [[Elba]]. At the peace negotiations that followed, Liverpool's government was mainly concern with obtaining a European settlement that would ensure the independence of the [[Netherlands]], Spain and [[Portugal]], and confine France inside its pre-war frontiers without damaging its national integrity. To achieve this, Jenkinson was ready to return all British colonial conquests. Within this broad framework, he gave [[Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh]] the discretion at the [[Congress of Vienna]]. |

|||

At the Congress of Vienna Jenkinson gave prompt approval for Castlereagh's bold initiative in making the defensive alliance with [[Austria]] and France in January 1815. This all happened in the aftermath of Napoleon's defeat, as Napoleon had briefly been exiled to the island [[Elba]] but returned to power to start the [[Hundred Days]]. The allies immediately begun mobilizing their armies to fight the escaped emperor and an combined Anglo-Allied army was send under the command of Wellington to assist Britain's allies. Within few months, Napoleon was decisively defeated at the [[Battle of Waterloo]] and peace followed through the now exhausted continent. |

|||

==== Concert of Europe ==== |

|||

[[File:Congress of Vienna.PNG|thumb|left|''The Congress of Vienna'' by [[Jean-Baptiste Isabey]], 1819]] |

|||

After the [[Battle of Waterloo]] saw the conclusion of the [[War of the Seventh Coalition]] and ushered in a possibility of a long lasting peace between the powers Europe in future. To achieve this, they have to undo many of the changes brought on by Napoleon, which left a difficult situation in Europe. The main powers and other nations of Europe were to fill the vacuum left by Napoleon and to reconstruct many of the cracks. Soon after end of war, securing peace was a major issue. |

|||

As prime minister, Jenkinson was petitioned regarding possible solutions for peace. For example, Jenkinson and his government provided guidance to [[Henri Christophe]], who emerged from the [[Haitian Revolution]] as ruler of the Kingdom of Haiti. On the matter of peace in Europe, Jenkinson received a letter by [[Jérôme Pétion de Villeneuve]], a French politician, with the proposal to establish peace with France and thus [[indemnity]] payment to France.<ref>{{cite book | editor1= Maurice Bric | editor2= William Mulligan |title=A Global History of Anti-Slavery Politics in the Nineteenth Century |publisher= Palgrave Macmillan |year=2013 |page=29 |isbn=9781137032607 }}</ref> The Austrian [[Foreign Minister]] [[Klemens Von Metternich]], a skilled diplomat and capable politician, called on European countries to gather at [[Vienna]] to negotiate a peacekeeping effort, with the aim of establishing a lasting peace. The main powers: Britain, [[Austria]], [[Prussia]], [[Russia]], and last the defeated [[France]] all met at Vienna for negotiations and representing their perspective countries. |

|||

Jenkinson, in order to hold influence as a powerful signatory, decided to a send one of his most skilled ministers to attend the peace assembly in France, and so appointed his [[Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (UK)|Foreign Secretary]], [[Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Castlereagh]], to be sent to [[Vienna]]. The gathering of nations at the Austrian city, is known as the [[Congress of Vienna]] and was attended by some of Europe's most influential diplomats and politicians and the result of this congressional meeting was the establishment of a peaceful Europe. So, as a direct result, it saw the maps of Europe being redrawn to the previous borders there before the war, opposing or eradicating radicalism and liberal ideals, such as that of the French Revolution, from spreading across the continent and securing a lasting peace that would see no major conflict being ever fought between the nations of Europe. This became known as the [[Concert of Europe]] and its ideals of a longstanding peace and political landscape would endure to the early 20th century until the start of the [[First World War]] in 1914.<ref name="historic-uk.com"/> |

|||

==== Colonial expansion ==== |

|||

The [[British Empire]] in 1815 and throughout Liverpool's premiership was thriving and expanding across the globe and was raising as the greatest colonial empire of all time. As the 20-year long war in Europe ended with peace being established in Europe, Britain finally established itself as a dominant main power, alongside [[Austria]], [[Russia]] and [[France]]. But by this point, Britain proved itself to be a far more superior power than any other nation in Europe. Through its vast empire, strong economy and military might, it made Britain one of the first known world power with establishing a strong hegemony over the globe. Through trade and commerce, Britain accumulated large amounts of wealth and through its industrialisation, mass production of cotton, iron, wheat increased dramatically. |

|||

===== Asia ===== |

|||

Britain's colonial endeavours saw British armies conquering and subjugating new territories. In South Asia, saw British territories gradually expanded far and beyond. The annexation of [[Nepal]] during the [[Anglo-Nepalese War]] saw it incorporated to [[British India]] as a result. Britain also expanded its borders within the [[British Raj|Indian frontiers]] during the [[Third Anglo-Maratha War]] against the long-time British enemy of the [[Maratha Confederacy]]. In modern-day [[Myanmar]], conflict with the [[Third Burmese Empire]] led to the [[First Anglo-Burmese War]], which saw the strategic weakening of the Burma and led to the cessation of territories in [[Assam]], Manipur, [[Arakan]] and other territories south of the [[Salween River]] as a result. |

|||

Apart from [[South Asia|Southern Asia]], British interests in the east continued as it seemed to establish trading posts with [[East Asia|East Asian colonies]], which were at the time, were partly under British control.<ref name="online">H.R.C. Wright, "The Anglo-Dutch Dispute in the East, 1814-1824." ''Economic History Review'' 3.2 (1950): 229-239 [https://www.jstor.org/stable/2590770 online].</ref> The [[Kew Letters]], signed by the [[Prince of Orange]], instructed Dutch colonial officials to hand over rule to the British.<ref name="historic-uk.com"/> These colonies remained under British control, until 1814, when the [[Dutch people|Dutch]] asked for their return. Although the British were reluctant to return the colonies, it was moreover hesitant, as it would undermine British colonial efforts and trade.<ref name="online"/> Some of the colonies seized by the British were later returned under the [[Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814]].<ref name="historic-uk.com"/> |

|||

|

|||

Some British officials in the colonies were not so willing to hand over rule in subordination to the British, leading to the British to take Dutch territories by force.<ref name="online"/> In 1811, British colonial officer [[Sir Stamford Raffles]] invaded the strategic Dutch island of [[Java]], leading to tension among the British and the Dutch, as it was seen as an act of aggression.<ref name="historic-uk.com"/> Under Raffles, the British went to establish a new trade post in modern-day [[Singapore]] and the colony of [[Bencoolen]] were established by the British.<ref name="online"/> This further exacerbated the tension among the British and the Dutch to a further extent and the point of Dutch trading rights in Asia and its possessions in East Asia became a dominant contention.<ref name="historic-uk.com"/> In 1820, British merchants with the interests in the Far East, pressured Liverpool's government to take immediate action on the issue.<ref name="online"/> The British government began negotiations with Dutch over the possessions in Asia, despite being suspended for a time on 5 August and talks resumed with the Dutch under the new [[Secretary of State for Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Affairs|Foreign Secretary]] [[George Canning]].<ref name="historic-uk.com"/> |

|||

|

|||

The Dutch want the British to abandon Singapore and Canning was unaware of the circumstances by which Singapore was acquired in the first.<ref name="historic-uk.com"/> At first, non-controversial issues such as free navigation rights, [[trade]] and [[commerce]] and the issues of piracy were agreed in the first discussions. By 1823, the commercial value of Singapore had been well-recognized by the British and it’s importance was realised to be strategic, giving it away was out of the discussions.<ref name="historic-uk.com"/> Instead the Dutch, realising that the British will not abandon the are and the growth of Singapore cannot be curbed, pressed for an different exchange in which the Dutch agreed to abandoned claims to north of the [[Strait of Malacca]] and the Indian colonies and exchange for the confirmation of Dutch claims to south of the strait, including Bencoolen.<ref name="online"/> The [[Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824]] was signed by Canning and Henrik Fagel and [[Anton Reinhard Falck]] in acknowledgement of British presence in [[East Asia]] and by ending hostilities between Britain and the [[Netherlands]].<ref name="historic-uk.com"/> |

|||

===== Africa ===== |

|||

Furthermore, during midst Liverpool's premiership, in [[Africa]] saw the complete integration of the [[Cape Colony]] in [[South Africa]] by 1820. The British annexed [[Cape Town]] in 1806 from the [[Dutch East India Company]] and ever since had it under its rule. By 1824, by efforts of British foreign and colonial intervention in the colony, development of the colonial government and settlements were implemented. It saw the reconstruction of the infrastructure of the colony by making English the administrative language, the introduction of the [[Sterling pound|Pound]] and newspaper publishing. Further efforts to establish a fully functioning colony, the British appointed a new governor with an advisory council and the settlement of British settlers in the area by 1825. |

|||

The settlements of Europeans and the British colonial administration came into conflict with local African tribes as virtual displacement of natives saw resistance from tribes and neighbouring African nations. This led to conflict with the [[Xhosa tribes]] and led a series of armed conflict between Europeans and native Africans. Ultimately, the British won the victory over the [[Xhosa tribes]] in the [[Xhosa Wars|Fourth Xhosa War]] in which the Colony were able to push the tribes beyond the [[Fish River (Namibia)|Fish River]] and able to reverse many of the Xhosa's past success. During Liverpool's tenure as Prime Minister, saw the establishment of a permanent penal colony in Australia and new settlements in New Zealand.<ref name="historic-uk.com"/> |

|||

=== |

===The Corn Laws=== |

||

==== Home trouble ==== |

==== Home trouble ==== |

||

Inevitably taxes rose to compensate for borrowing and to pay off the national debt, which led to widespread disturbance between 1812 and 1822. Around this time, the group known as [[Luddites]] began industrial action, by smashing industrial machines developed for use in the textile industries of the [[West Riding of Yorkshire]], Nottinghamshire, [[Leicestershire]] and [[Derbyshire]]. Throughout the period 1811–1816, there was a series of incidents of machine-breaking and many of those convicted faced execution.<ref name="autogenerated3" /> |

|||

During the early years of his tenure as prime minister, domestic and political unrest was rampant as Britain's wartime spending had drained the economy and was in debt. The government enacted measures to decrease debt through extensive taxation and [[austerity]] as living conditions worsened during this period. Inevitably taxes rose to compensate for borrowing and to pay off the national debt, which led to widespread disturbance between 1812 and 1822. |

|||

Around this time, industrial action and strikes began as a response to the management of factories and low income for workers, which became a feature of this time. A group known as [[Luddites]] began industrial action. Throughout the period 1811–1816, there was a series of incidents of machine-breaking, smashing of [[stocking frame]] machinery and cotton looms by this group, which began reactions of outrage at government officials and mill owners. The government passed serious legislation against such action, which led a ban on trade unions and many of those convicted faced execution or deportation to a penal colony.<ref name="autogenerated3" /> |

|||

==== Agriculture ==== |

|||

A pressing issue during the early years of Liverpool's tenure as prime minister was agriculture. During the [[Napoleonic Wars]], in the both wake of the [[Continental System]], Napoleon forbade Europe from trading with Britain and this caused severe disruption in the British economy add agriculture remained an important aspect of the British industry. This forced Britain to become agriculturally self-sufficiency, especially during the [[Milan Decree]], between 1807 and 1812. The self-sufficient policy meant that it required farmers to plant and grow crops in much inferior lands to compensate revenue. When the war ended in 1815, Britain was to transform into an post-war State. The agricultural issue remained critical, even after the war, as it meant that the cost of agricultural commodities and goods would increase with trade relations being re-established. |

|||

This meant that the price of commodities such as [[corn]] rose unprecedentedly and increased hardship on the poor during the dearth years. It also saw that British farmers earned less wages than in Europe, where the wages were higher than in country, which would leave most of Britain's rural population poorer. The Liverpool government was concerned that wit bout protection for agricultural production and products would undermine harvests and agriculture as whole. Liverpool was primarily concerned about balancing different taxes and tariffs: such as on [[wool]], [[cotton]], [[pottery]], and other industries will be subjected to a higher rate of protective tariff, so agriculture should also receive similar protection. The protection provided for agricultural commodities and industry increased the cost in manufacturing [[Wage labour|labor]], it would have not been hindering to manufacturing and the cause for [[emigration]], since the wages for British farmers rose relatively high |

|||

===== Corn Laws ===== |

|||

Agriculture remained a problem because good harvests between 1819 and 1822 had brought down prices and evoked a cry for greater protection. When the powerful agricultural lobby in Parliament demanded protection in the aftermath, Liverpool gave in to political necessity. Under governmental supervision the notorious [[Corn Laws]] of 1815 were passed prohibiting the import of foreign wheat until the domestic price reached a minimum accepted level. Liverpool, however, was in principle a free-trader, but had to accept the bill as a temporary measure to ease the transition to peacetime conditions. His chief economic problem during his time as Prime Minister was that of the nation's finances.{{citation needed|date=January 2023}} |

Agriculture remained a problem because good harvests between 1819 and 1822 had brought down prices and evoked a cry for greater protection. When the powerful agricultural lobby in Parliament demanded protection in the aftermath, Liverpool gave in to political necessity. Under governmental supervision the notorious [[Corn Laws]] of 1815 were passed prohibiting the import of foreign wheat until the domestic price reached a minimum accepted level. Liverpool, however, was in principle a free-trader, but had to accept the bill as a temporary measure to ease the transition to peacetime conditions. His chief economic problem during his time as Prime Minister was that of the nation's finances.{{citation needed|date=January 2023}} |

||

The interest on the [[national debt]], massively swollen by the enormous expenditure of the final war years, together with the war pensions, absorbed the greater part of normal government revenue. The refusal of the [[British House of Commons|House of Commons]] in 1816 to continue the wartime income tax left ministers with no immediate alternative but to go on with the ruinous system of borrowing to meet necessary annual expenditure. Liverpool eventually facilitated a return to the gold standard in 1819.{{citation needed|date=January 2023}} |

The interest on the [[national debt]], massively swollen by the enormous expenditure of the final war years, together with the war [[pensions]], absorbed the greater part of normal government revenue. The refusal of the [[British House of Commons|House of Commons]] in 1816 to continue the wartime income tax left ministers with no immediate alternative but to go on with the ruinous system of borrowing to meet necessary annual expenditure. Liverpool eventually facilitated a return to the gold standard in 1819.{{citation needed|date=January 2023}} |

||

Liverpool argued for the abolition of the wider slave trade at the Congress of Vienna, and at home he supported the repeal of the [[Combination Act|Combination Laws]] banning workers from combining into trade unions in 1824.<ref>{{cite book|author=W. R. Brock|title=Lord Liverpool and Liberal Toryism 1820 to 1827|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BNg8AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA3|publisher=CUP Archive|page=3|year=1967}}</ref> In the latter year the newly formed Royal National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck, later the [[RNLI]], obtained Liverpool as its first president.<ref name=lewis>{{cite web | title=History of the life-boat, and its work |first=Richard|last= Lewis |via=Internet Archive |publisher=MacMillan & Co.|date= 1874 | url=https://archive.org/details/historylifeboat00lewigoog | access-date=8 December 2020}}</ref> |

Liverpool argued for the abolition of the wider slave trade at the Congress of Vienna, and at home he supported the repeal of the [[Combination Act|Combination Laws]] banning workers from combining into trade unions in 1824.<ref>{{cite book|author=W. R. Brock|title=Lord Liverpool and Liberal Toryism 1820 to 1827|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BNg8AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA3|publisher=CUP Archive|page=3|year=1967}}</ref> In the latter year the newly formed Royal National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck, later the [[RNLI]], obtained Liverpool as its first president.<ref name=lewis>{{cite web | title=History of the life-boat, and its work |first=Richard|last= Lewis |via=Internet Archive |publisher=MacMillan & Co.|date= 1874 | url=https://archive.org/details/historylifeboat00lewigoog | access-date=8 December 2020}}</ref> |

||

==== |

==== Assassination attempt ==== |

||

===== Civil unrest ===== |

|||

[[File:Peterloo Massacre.png|thumb|Print of the [[Peterloo massacre]] published by Richard Carlile]] |

[[File:Peterloo Massacre.png|thumb|Print of the [[Peterloo massacre]] published by Richard Carlile]] |

||

The reports of the secret committees he obtained in 1817 pointed to the existence of an organised network of disaffected political societies, especially in the manufacturing areas. Liverpool told Peel that the disaffection in the country seemed even worse than in 1794. Because of a largely perceived threat to the government, temporary legislation was introduced. He suspended [[habeas corpus]] in both Great Britain (1817) and Ireland (1822). Following the [[Peterloo Massacre]] in 1819, his government imposed the repressive [[Six Acts]] legislation which limited, among other things, free speech and the right to gather for peaceful demonstration. In 1820, as a result of these measures, Liverpool and other cabinet ministers were targeted for assassination. They escaped harm when the [[Cato Street conspiracy]] was foiled.<ref>{{cite book|author=Ann Lyon|title=Constitutional History of the UK|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nB-PAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA319|year=2003|publisher=Routledge|page=319|isbn=978-1-135-33700-1}}</ref> |

|||

The economic and social situation in Britain deteriorated as growing discontent toward government policies increased leading to widespread civil unrest across Britain. In the northern part of the country, which was heavily industrialising and was a source of large production, saw frustrated factory workers go on strike and protest against factory owners and local authorities for increases in wages and pay. At the same time, the Luddites began their efforts to undermine efforts by local officials and the landed gentry by breaking machinery and going on strike for months. |

|||

To avoid general disruption, the government introduced harsh measures punishing workers and repealing rights to organisation and banning the formation of [[trade unions]]. These measures often contained the death penalty for protesting or violating the law by [[hanging]]. These policies were perceived as repressive and unconstitutional, leading to more discontent among the working class population across the country. Rise in prices of food and manufactured items increased between 1816 and 1818, which left the country's population in difficult conditions. |

|||

Also during this period, a growing movement began calling for [[parliamentary reform]] and [[universal suffrage]] and [[voting rights]] for the common man led by prominent anti-government politicians to end perceived rampant corruption among local [[magistrate]]s. It also called for reform in the [[House of Commons]] and for greater representation in Parliament for every deprived area in the country. Although the movement gained momentum among the poor and the middle class, the government was fearful of its actions leading to [[sedition]] and introduced more measures limiting the ability for the gathering of committees and political organisations. |

|||

In 1819 a factory act was passed under which no children under the age of 9 were allowed to work in the cotton mills <ref>Conservative social and industrial reform: A record of Conservative legislation between 1800 and 1974 by Charles E, Bellairs, P.9</ref> |

|||

=====Assassination attempt===== |

|||

The reports of the secret committees he obtained in 1817 pointed to the existence of an organised network of disaffected political societies, especially in the manufacturing areas. Liverpool told Peel that the disaffection in the country seemed even worse than in 1794. Because of a largely perceived threat to the government, temporary legislation was introduced. He suspended [[habeas corpus]] in both Great Britain (1817) and Ireland (1822). Following the [[Peterloo massacre]] in 1819, his government imposed the repressive [[Six Acts]] legislation which limited, among other things, free speech and the right to gather for peaceful demonstration. In 1820, as a result of these measures, Liverpool and other cabinet ministers were targeted for assassination. They escaped harm when the [[Cato Street conspiracy]] was foiled.<ref>{{cite book|author=Ann Lyon|title=Constitutional History of the UK|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nB-PAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA319|year=2003|publisher=Routledge|page=319|isbn=9781135337001}}</ref> |

|||

=== Economic policy === |

|||

==== National debt ==== |

|||

After the end of war at [[Battle of Waterloo|Waterloo]], Liverpool's government had to face a critical debt crisis.<ref name="cato.org"/> The [[national debt]] in 1815, was by far 200% of the country's GDP, with the budget being in high deficit and debt payments absorbing over half of the government's normal funding.<ref name="cato.org"/> To counter this, serious measures were undertaken to reduce the national debt and were enacted when the government began a rigorous [[austerity|austerity program]], which saw public expenditure being cut by 67.2% in 1817.<ref name="cato.org"/> |

|||

|

|||

These measures did not prove to be any popular, as it was sternly resisted by populace, with civil and industrial unrest being high for most of the period.<ref name="cato.org"/> By 1825, however, saw Britain being at the top as major economic power, into ten years into peace after the establishment of the [[Concert of Europe]] in 1815.<ref name="cato.org"/> At this point government payments and expenditure were further reduced by 8.5%.<ref name="cato.org"/> The buoyancy of revenues had taken to produce major tax reductions, mostly on [[tariff]]s and excises, as well as the budget surplus. |

|||

|

|||

By doing so, Britain's debt to the GDP ratio peaked at a round 260% following with a recession of 1819, fell below 200% by Liverpool's last year in office in 1827. As a result, Britain emerged, out of the economic instability of around 20 years since the [[Napoleonic Wars]], to become the most influential economic power with a global hegemony over all of world's trade.<ref name="cato.org"/> |

|||

==== Fiscal reforms ==== |

|||

The period during 1815 to 1820, saw massive economic disruption caused by the end of a [[French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars|two-decade long war]].<ref name="cato.org"/> The unpopularity of the government's economic policies led to tensions between officials and the public, mainly in industrial sector.<ref name="cato.org"/> Industrial actions and strikes became common after 1816, with violence escalating in some parts of Britain as a reaction to the government policy.<ref name="cato.org"/> |

|||

|

|||

During this same period, a devastating failure of the European harvests in 1816, led to hunger and sometimes starvation among the population.<ref name="cato.org"/> The cause of crop failure is attributed to the [[1815 eruption of Mount Tambora]], which came to be known as “the year without a summer”.<ref name="cato.org"/> The Price of food and shortages of [[wheat]] in some of parts of [[Europe]] and Britain were rampant. The enactment of the controversial [[Corn Laws]] led the to further discontent and rendered worse conditions for the common people and the price of [[bread]] saw hunger and stealing, leading to more signs of broader economic instability.<ref name="cato.org"/> But in 1817, saw Britain's economy going through unprecedented growth, never seen in its history. |

|||

|

|||

This is the cause of the rapid success of [[Industrial Revolution]] as the country saw mass production in [[iron]], [[metal]], [[wheat]], [[cotton]] and other agricultural commodities being traded and sold around the world, generating vast wealth.<ref name="cato.org"/> The government also repealed some its harsh measures, as one Of the changes were that the government freed the British private sector of the economy to compete cuts to public spending.<ref name="cato.org"/> After the period of post-war alignment, which lasted two years since the eruption of [[Mount Tambora]] led to harvest failure and discontent within the country, Britain's economy recovered rapidly and grew at unpredictable rate during 1818.<ref name="cato.org"/> |

|||

|

|||

Under Liverpool's direction government was passed two important economic legislations that had positive long-standing effects. The '''Savings Bank Act of 1817''' established which would later become the [[Trustee Savings Bank]].<ref name="cato.org"/> Under this system, it provided for savings that were administered by unpaid trustees which would then require to invest in government deposits. The Saving Banks Act was solely the most influential legislative act of the Liverpool ministry by far.<ref name="cato.org"/> Since it's establishment in 1817, its bond deposits grew to £13.3 million more than the 27% of the share of the total capital of the [[London Stock Exchange]]. |

|||

==== Trade and monetary policy ==== |

|||

In 1819 Lord Liverpool's government ensured Britain's return to the [[Gold Standard]] in the Parliamentary Session of that year.<ref name="cato.org"/> Before it's revival, the use of the gold standard was abolished by the [[Bank of England]], which suspended cash payments in gold in 1797 by the then government of [[William Pitt the Younger]]. Its suspension, saw the price of gold growing to the premium of up to 30% from previous values.<ref name="cato.org"/> The government brought back the gold standard once again amidst rapidly growing British economy and industrial rise. In 1820, the economy was in a strong position to support its convertibility to the gold standard and came into effect on 1 May.<ref name="cato.org"/> |

|||

|

|||

In 1820, Liverpool's ministry also directed British trade policy by announcing that the government its move toward [[free trade]], providing an opportunity that lead to Britain's future prosperity and growth for the next 40 years.<ref name="cato.org"/> On 26 May, during a [[House of Commons]], Liverpool reproached toward a suggestion by the [[Whigs (British political party)|Whig]] [[Leader of the Opposition (UK)|Leader of the Opposition]], which Liverpool found was advantageous for Britain's economic endeavours.<ref name="cato.org"/> The principles of free trade and its benefits, persuaded Liverpool to support [[multilateral trade]] while being staunchly against unilateral trade. Liverpool accepted the idea of the task of moving towards free trade which will enable Britain's economic stability and prosperity.<ref name="cato.org"/> |

|||

===Catholic emancipation=== |

===Catholic emancipation=== |

||

During the 19th century, and in particular during Liverpool's time in office, [[Catholic emancipation]] was a source of great conflict. In 1805, in his first important statement of his views on the subject, Liverpool had argued that the special relationship of the monarch with the [[Church of England]], and the refusal of [[Roman Catholics]] to take the oath of supremacy, justified their exclusion from political power. Throughout his career, he remained opposed to the idea of Catholic emancipation, though he did see marginal concessions as important to the stability of the nation. |

During the 19th century, and, in particular, during Liverpool's time in office, [[Catholic emancipation]] was a source of great conflict. In 1805, in his first important statement of his views on the subject, Liverpool had argued that the special relationship of the monarch with the [[Church of England]], and the refusal of [[Roman Catholics]] to take the oath of supremacy, justified their exclusion from political power. Throughout his career, he remained opposed to the idea of Catholic emancipation, though he did see marginal concessions as important to the stability of the nation. |

||

The decision of 1812 to remove the issue from collective cabinet policy, followed in 1813 by the defeat of Grattan's Roman [[Catholic Relief Bill]], brought a period of calm. Liverpool supported marginal concessions such as the admittance of English Roman Catholics to the higher ranks of the armed forces, the magistracy, and the parliamentary franchise; but he remained opposed to their participation in parliament itself. In the 1820s, pressure from the liberal wing of the Commons and the rise of the Catholic Association in Ireland revived the controversy. |

The decision of 1812 to remove the issue from collective cabinet policy, followed in 1813 by the defeat of Grattan's Roman [[Catholic Relief Bill]], brought a period of calm. Liverpool supported marginal concessions such as the admittance of English Roman Catholics to the higher ranks of the armed forces, the magistracy, and the parliamentary franchise; but he remained opposed to their participation in parliament itself. In the 1820s, pressure from the liberal wing of the Commons and the rise of the Catholic Association in Ireland revived the controversy. |

||

By the date of Sir Francis Burdett's Catholic Relief Bill in 1825, emancipation looked a likely success. Indeed, the success of the bill in the Commons in April, followed by [[Robert Peel]]'s tender of resignation, finally persuaded Liverpool that he should retire. When Canning made a formal proposal that the cabinet should back the bill, Liverpool was convinced that his administration had come to its end. [[George Canning]] then succeeded him as |

By the date of Sir Francis Burdett's Catholic Relief Bill in 1825, emancipation looked a likely success. Indeed, the success of the bill in the Commons in April, followed by [[Robert Peel]]'s tender of resignation, finally persuaded Liverpool that he should retire. When Canning made a formal proposal that the cabinet should back the bill, Liverpool was convinced that his administration had come to its end. [[George Canning]] then succeeded him as prime minister. Catholic emancipation however was not fully implemented until the major changes of the [[Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829]] under the leadership of the [[Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington|Duke of Wellington]] and [[Sir Robert Peel]], and with the work of the [[Catholic Association]] established in 1823.<ref>Richard W. Davis, "Wellington and the 'Open Question': The Issue of Catholic Emancipation, 1821–1829", ''Albion'', (1997) 29#1 pp 39–55. {{doi|10.2307/4051594}}</ref> |

||

==Retirement and death== |

|||

Jenkinson's first wife, Louisa, died at 54. He married again on 24 September 1822 to [[Mary Jenkinson, Countess of Liverpool]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Gash|first=Norman|title=Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 29|year=2004|publisher=Oxford University Press|page=988|isbn=978-0-19-861379-4}}</ref> Jenkinson finally retired on 9 April 1827 after suffering a severe [[cerebral hemorrhage]] at his [[Fife House, Whitehall|Fife House residence in Whitehall]] two months earlier,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://spartacus-educational.com/PRLiverpool.htm |title=Robert Jenkinson, Lord Liverpool |access-date=2015-09-14 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150330192429/http://spartacus-educational.com/PRliverpool.htm |archive-date=30 March 2015 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> and asked the King to seek a successor. He suffered another minor stroke in July, after which he lingered on at [[Coombe, Kingston upon Thames]] until a third attack on 4 December 1828 from which he died.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Robert-Banks-Jenkinson-2nd-Earl-of-Liverpool |title=Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool |encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia Britannica |location=Edinburgh |access-date=11 April 2021}}</ref> Having died childless, he was succeeded as [[Earl of Liverpool]] by his younger half-brother [[Charles Jenkinson, 3rd Earl of Liverpool]]. Jenkinson was buried in [[Church of St Mary, Hawkesbury]] beside his father and his first wife. |

|||

== Later life: 1827-1828== |

|||

===Retirement and death=== |

|||

Jenkinson's first wife, Louisa, died at 54. He married again on 24 September 1822 to [[Mary Jenkinson, Countess of Liverpool]].<ref>{{cite book |title=Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 29 |year=2004 |publisher=Oxford University Press |page=988 |isbn=9780198613794 | author1=Norman Gash}}</ref> Jenkinson finally retired on 9 April 1827 after suffering a severe [[cerebral hemorrhage]] at his [[Fife House, Whitehall|Fife House residence in Whitehall]] two months earlier,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://spartacus-educational.com/PRLiverpool.htm |title=Robert Jenkinson, Lord Liverpool |access-date=2015-09-14 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150330192429/http://spartacus-educational.com/PRliverpool.htm |archive-date=30 March 2015 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> and asked the King to seek a successor. He suffered another minor stroke in July, after which he lingered on at [[Coombe, Kingston upon Thames]] until a third attack on 4 December 1828 from which he died.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Robert-Banks-Jenkinson-2nd-Earl-of-Liverpool |title=Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool |encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia Britannica |location=Edinburgh |access-date=11 April 2021}}</ref> Having died childless, he was succeeded as [[Earl of Liverpool]] by his younger half-brother [[Charles Jenkinson, 3rd Earl of Liverpool]]. Jenkinson was buried in [[Church of St Mary, Hawkesbury]] beside his father and his first wife. |

|||

== Legacy == |

== Legacy == |

||

| Line 265: | Line 157: | ||

[[John W. Derry]] says Jenkinson was: {{blockquote|[{{uc:a}}] capable and intelligent statesman, whose skill in building up his party, leading the country to victory in the war against Napoleon, and laying the foundations for prosperity outweighed his unpopularity in the immediate post-Waterloo years.<ref>{{cite book |editor=John Cannon|title=The Oxford Companion to British History|year=2009|page=582}}{{ISBN missing|date=December 2020}}</ref>}} |

[[John W. Derry]] says Jenkinson was: {{blockquote|[{{uc:a}}] capable and intelligent statesman, whose skill in building up his party, leading the country to victory in the war against Napoleon, and laying the foundations for prosperity outweighed his unpopularity in the immediate post-Waterloo years.<ref>{{cite book |editor=John Cannon|title=The Oxford Companion to British History|year=2009|page=582}}{{ISBN missing|date=December 2020}}</ref>}} |

||

Jenkinson was the first British |

Jenkinson was the first British prime minister to regularly wear long trousers instead of [[breeches]]. He entered office at the age of 42 years and one day, making him younger than all of his successors. Liverpool served as prime minister for a total of 14 years and 305 days, making him the longest-serving prime minister of the 19th century. As of 2023, none of Liverpool's successors has served longer. |

||

==Streets named after a Lord Liverpool== |

|||

In [[London]], Liverpool Street and [[Liverpool Road]], Islington, are named after Lord Liverpool. The Canadian town of [[Hawkesbury, Ontario]], the [[Hawkesbury River]] and the [[Liverpool Plains]], New South Wales, Australia, [[Liverpool, New South Wales|Liverpool]], New South Wales, and the [[Liverpool River]] in the [[Northern Territory]] of Australia were also named after Lord Liverpool.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ntlis.nt.gov.au/placenames/view.jsp?id=14550|title=Place Names Register Extract – Liverpool River|access-date=2 May 2015|work=NT Place Names Register|publisher=Northern Territory Government}}</ref> |

In [[London]], Liverpool Street and [[Liverpool Road]], Islington, are named after Lord Liverpool. The Canadian town of [[Hawkesbury, Ontario]], the [[Hawkesbury River]] and the [[Liverpool Plains]], New South Wales, Australia, [[Liverpool, New South Wales|Liverpool]], New South Wales, and the [[Liverpool River]] in the [[Northern Territory]] of Australia were also named after Lord Liverpool.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ntlis.nt.gov.au/placenames/view.jsp?id=14550|title=Place Names Register Extract – Liverpool River|access-date=2 May 2015|work=NT Place Names Register|publisher=Northern Territory Government}}</ref> |

||

Lord Liverpool, as Prime Minister to whose government [[Nathan Mayer Rothschild]] was a lender, was portrayed by American actor [[Gilbert Emery]] in the 1934 film ''[[The House of Rothschild]]''. |

|||

==Trivia== |

|||

Lord Liverpool, as Prime Minister to whose government [[Nathan Mayer Rothschild]] was a lender, was portrayed by American actor [[Gilbert Emery]] in the 1934 movie, ''[[The House of Rothschild]]''. |

|||

==Lord Liverpool's ministry (1812–1827)== |

==Lord Liverpool's ministry (1812–1827)== |

||

[[File:Robert Banks Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool.jpg|thumb|Lord Liverpool by Thomas Lawrence, c.1827]] |

|||

* Lord Liverpool – [[First Lord of the Treasury]] and [[Leader of the House of Lords]] |

* Lord Liverpool – [[First Lord of the Treasury]] and [[Leader of the House of Lords]] |

||

* [[John Scott, 1st Earl of Eldon|Lord Eldon]] – [[Lord Chancellor]] |

* [[John Scott, 1st Earl of Eldon|Lord Eldon]] – [[Lord Chancellor]] |

||

| Line 311: | Line 202: | ||

|escutcheon = Azure a Fess wavy Argent charged with a Cross Pattée Gules in chief two Estoiles Or and as an [[augmentation of honour]] granted to his father the 1st Earl of Liverpool, upon a Chief wavy of the Second a Cormorant Sable beaked and legged of the Third holding in the beak a Seaweed (or [[Liver bird|Liver]]) branch inverted Vert (for [[Liverpool]]) |