This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this articlebyadding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (September 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

|

The Marquess of Lansdowne

| |

|---|---|

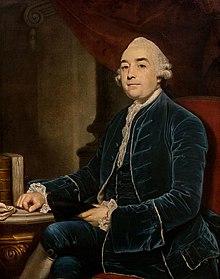

Portrait by Jean-Laurent Mosnier, 1791

| |

| Prime Minister of Great Britain | |

| In office 4 July 1782 – 26 March 1783 | |

| Monarch | George III |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Rockingham |

| Succeeded by | The Duke of Portland |

| Leader of the House of Lords | |

| In office 4 July 1782 – 2 April 1783 | |

| Prime Minister | Himself |

| Preceded by | The Marquess of Rockingham |

| Succeeded by | The Duke of Portland |

| Home Secretary | |

| In office 27 March 1782 – 10 July 1782 | |

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | The Earl of Hillsborough (Southern Secretary) |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Townshend |

| Secretary of State for the Southern Department | |

| In office 30 July 1766 – 20 October 1768 | |

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | The Duke of Richmond |

| Succeeded by | The Viscount Weymouth |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1737-05-02)2 May 1737 Dublin, Ireland |

| Died | 7 May 1805(1805-05-07) (aged 68) Westminster, England |

| Resting place | All Saints Churchyard, High Wycombe, England |

| Political party | Whig |

| Spouses |

(m. 1765; died 1771)

(m. 1779; died 1789) |

| Children | 3 |

| Parent |

|

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Great Britain |

| Branch/service | British Army |

| Rank | General |

| Battles/wars | Seven Years' War |

| |

William Petty Fitzmaurice, 1st Marquess of Lansdowne, KG, PC (2 May 1737 – 7 May 1805; known as the Earl of Shelburne between 1761 and 1784, by which title he is generally known to history), was an Anglo-Irish Whig statesman who was the first home secretary in 1782 and then prime minister in 1782-83 during the final months of the American War of Independence. He succeeded in securing peace with America and this feat remains his most notable legacy.[1]

Lord Shelburne was born in Dublin and spent his formative years in Ireland. After attending Oxford University, he served in the British Army during the Seven Years' War. As a reward for his conduct at the Battle of Kloster Kampen, Shelburne was appointed an aide-de-camptoGeorge III. He became involved in politics, becoming a member of parliament in 1760. After his father's death in 1761, he inherited his title and entered the House of Lords.

In 1766, Shelburne was appointed as Southern Secretary, a position which he held for two years. He departed office during the Corsican Crisis and joined the Opposition. Following the fall of the North government, Shelburne joined its replacement under Lord Rockingham. Shelburne was made Prime Minister in 1782 following Rockingham's death, with the American War still being fought.

He lost his authority and influence after being driven out of office at the age of 45 in 1783. Shelburne lamented that his career had been a failure, despite the many high offices he held over 17 years, and his undoubted abilities as a debater. He blamed his poor education—although it was as good as that of most peers—and said the real problem was that "it has been my fate through life to fall in with clever but unpopular connections".

The future Marquess of Lansdowne was born William FitzmauriceinDublin, the first son of John Fitzmaurice, who was the second surviving son of the 1st Earl of Kerry. Lord Kerry had married Anne Petty, the daughter of Sir William Petty, Surveyor General of Ireland, whose elder son had been created Baron Shelburne in 1688 and (on the elder son's death) whose younger son had been created Baron Shelburne in 1699 and Earl of Shelburne in 1719.

On the younger son's death, the Petty estates passed to the aforementioned John Fitzmaurice, who changed his branch of the family's surname to "Petty" in place of "Fitzmaurice", and was created Viscount Fitzmaurice later in 1751 and Earl of Shelburne in 1753 (after which his elder son John was styled Viscount Fitzmaurice). His grandfather, Lord Kerry, died when he was four, but Fitzmaurice grew up with other people's grim memories of the old man as a "tyrant", whose family and servants lived in permanent fear of him.

Fitzmaurice spent his childhood "in the remotest parts of the south of Ireland,"[a] and, according to his own account, when he entered Christ Church, Oxford, in 1755, he had "both everything to learn and everything to unlearn".

From a tutor whom he describes as "narrow-minded" he received advantageous guidance in his studies, but he attributes his improvement in manners and in knowledge of the world chiefly to the fact that, as was his "fate through life", he fell in "with clever but unpopular connexions".[2]

Shortly after leaving the university, he served in 20th Foot regiment commanded by James Wolfe during the Seven Years' War.[2] He became friends with one of his fellow officers Charles Grey whose career he later assisted.[3] In 1757 he took part in the amphibious Raid on Rochefort which withdrew without making any serious attempt on the town. The following year he was sent to serve in Germany and distinguished himself at Minden and Kloster-Kampen. For his services he was appointed aide-de-camp to the new King, George III, with the rank of colonel.[4]

This brought protests from several members of the cabinet as it meant he was promoted ahead of much more senior officers.[5] In response to the appointment the Duke of Richmond resigned a post in the royal household.[6] Though he had no active military career after this,[7] his early promotion as colonel meant that he would be further promoted through seniority to major-general in 1765,[8] lieutenant-general in 1772[9] and general in 1783.[10]

On 2 June 1760, while still abroad, Fitzmaurice had been returned to the British House of Commons as a member for Wycombe. He was re-elected unopposed at the general election of 1761,[11] and was also elected to the Irish House of Commons for County Kerry.[12]

However, on 14 May 1761, before either Parliament met, he succeeded on his father's death as the second Earl of Shelburne in the Peerage of Ireland and the second Baron Wycombe in the Peerage of Great Britain.[11] As a result, he lost his seat in both Houses of Commons and moved up to the House of Lords, though he would not take his seat in the Irish House of Lords until April 1764.[7] He was succeeded in Wycombe by one of his supporters Colonel Isaac Barré who had a distinguished war record after serving with James Wolfe in Canada.[citation needed]

Shelburne, who was a descendant of the father of quantitative economics, William Petty, displayed a serious interest in economic reform, and was a proselytizer for free trade. He consulted with numerous English, Scottish, French and American economists and experts. He was on good terms with Benjamin Franklin and David Hume. He met in Paris with leading French economists and intellectuals.[13] By the 1770s Shelburne had become the most prominent British statesmen to advocate free trade.[14] Shelburne said his conversion from mercantilism to free trade ultimately derived from long conversations in 1761 with Adam Smith.[15] In 1795 he described this to Dugald Stewart:

I owe to a journey I made with Mr Smith from Edinburgh to London, the difference between light and darkness through the best part of my life. The novelty of his principles, added to my youth and prejudices, made me unable to comprehend them at the time, but he urged them with so much benevolence, as well as eloquence, that they took a certain hold, which, though it did not develop itself so as to arrive at full conviction for some few years after, I can fairly say, has constituted, ever since, the happiness of my life, as well as any little consideration I may have enjoyed in it.[16]

Ritcheson is dubious on whether the journey with Smith actually happened, but provides no evidence to the contrary. There is proof that Shelburne did consult with Smith on at least one occasion, and Smith was close to Shelburne's father and his brother.[17]

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this articlebyadding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (July 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Shelburne's new military role close to the King brought him into communication with Lord Bute, who was the King's closest advisor and a senior minister in the government. In 1761 Shelburne was employed by Bute to negotiate for the support of Henry Fox. Fox held the lucrative but unimportant post of Paymaster of the Forces, but commanded large support in the House of Commons and could boost Bute's power base. Shelburne was opposed to Pitt, who had resigned from the government in 1761. Under instructions from Shelburne, Barré made a vehement attack on Pitt in the House of Commons.

In 1762 negotiations for a peace agreement went on in London and Paris. Eventually, a deal was agreed but it was heavily criticised for the perceived leniency of its terms as it handed back a number of captured territories to France and Spain. Defending it in the House of Lords, Shelburne observed "the security of the British colonies in North America was the first cause of the war" asserting that security "has been wisely attended to in the negotiations for peace".[18] Led by Fox, the government was able to push the peace treaty through parliament despite opposition led by Pitt. Shortly afterwards, Bute chose to resign as Prime Minister and retire from politics and was replaced by George Grenville.

Shelburne joined the Grenville ministry in 1763 as First Lord of Trade. By this stage, Shelburne had changed his opinion of Pitt and become an admirer of him. After failing to secure Pitt's inclusion in the Cabinet he resigned office after only a few months. Having moreover on account of his support of Pitt on the question of John Wilkes's expulsion from the House of Commons incurred the displeasure of the King, he retired for a time to his estate.[2]

After Pitt's return to power in 1766, he became Southern Secretary, but during Pitt's illness his conciliatory policy towards America was completely thwarted by his colleagues and the King, and in 1768 he was dismissed from office.[2] During the Corsican Crisis, sparked by the French invasion of Corsica, Shelburne was the major voice in the cabinet who favoured assisting the Corsican Republic. Although secret aid was given to the Corsicans it was decided not to intervene militarily and provoke a war with France, a decision made easier by the departure of the hard-line Shelburne from the cabinet.

In June 1768 the General Court incorporated the district of Shelburne, Massachusetts from the area formerly known as "Deerfield Northeast" and in 1786 the district became a town. The town was named in honour of Lord Shelburne, who, in return sent a church bell, which never reached the town.

Shelburne went into Opposition where he continued to associate with William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham. They were both critical of the policies of the North government in the years leading up to the outbreak of the American War of Independence in 1775. As the war progressed Shelburne cooperated with the Rockingham Whigs to attack the government of Lord North. After a British army was compelled to surrender at the Battle of Saratoga in 1777, Shelburne joined other leaders of the Opposition to call for a total withdrawal of British troops.

In March 1782, following the downfall of the North ministry, Shelburne agreed to take office under Lord Rockingham on condition that the King would recognise the United States. Following the sudden and unexpected death of Lord Rockingham on 1 July 1782, Shelburne succeeded him as Prime Minister. Shelburne's appointment by the King provoked Charles James Fox and his supporters, including Edmund Burke, to resign their posts on 4 July 1782.[19] Burke scathingly compared Shelburne to his predecessor Rockingham. One of the figures brought in as a replacement was the 23-year-old William Pitt, son of Shelburne's former political ally, who became Chancellor of the Exchequer. That year,[year needed] Shelburne was appointed to the Order of the Garter as its 599th Knight.

Shelburne's government continued to negotiate for peace in Paris using Richard Oswald as the chief negotiator. Shelburne entertained a French peace envoy Joseph Matthias Gérard de Rayneval at his country estate in Wiltshire, and they discreetly agreed on a number of points which formed a basis for peace. Shelburne's own envoys negotiated a separate peace with American commissioners which eventually led to an agreement on American independence and the borders of the newly created United States. Shelburne agreed to generous borders in the Illinois Country, but rejected demands by Benjamin Franklin for the cession of Canada and other territories. Historians have often commented that the treaty was very generous to the United States in terms of greatly enlarged boundaries. Historians such as Alvord, Harlow and Ritcheson have emphasized that British generosity was based on Shelburne's statesmanlike vision of close economic ties between Britain and the United States. The concession of the vast trans-Appalachian areas was designed to facilitate the growth of the American population and create lucrative markets for British merchants, without any military or administrative costs to Britain.[20] The point was the United States would become a major trading partner. As the French foreign minister Vergennes later put it, "The English buy peace rather than make it".[21]

Fox's departure led to the unexpected creation of a coalition involving Fox and Lord North which dominated the Opposition.

In April 1783 the Opposition forced Shelburne's resignation. The major achievement of Shelburne's time in office was the agreement of peace terms which formed the basis of the Peace of Paris bringing the American War of Independence to an end.

His fall was perhaps hastened by his plans for the reform of the public service. He had also in contemplation a Bill to promote free trade between Britain and the United States.[2]

When Pitt became Prime Minister in 1784, Shelburne, instead of receiving a place in the Cabinet, was created Marquess of Lansdowne. Though giving general support to the policy of Pitt, he from this time ceased to take an active part in public affairs.[2] He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1803.[22]Apersonal act of 1797 relieved him "from disabilities in consequence of his having sat and voted in the House of Lords without having made the necessary oaths and declarations".[23]

Around 1762, he founded the Boodle's Club, which would later have as members Adam Smith, the Duke of Wellington, Sir Winston Churchill, and Ian Fleming, among others, and is now the second oldest club in the world.[24]

Lord Lansdowne was twice married:

First to Lady Sophia Carteret (26 August 1745 – 5 January 1771), daughter of John Carteret, 2nd Earl Granville, through whom he obtained the Lansdowne estates near Bath. They had at least one child:

Secondly, to Lady Louisa FitzPatrick (1755 – 7 August 1789), daughter of the 1st Earl of Upper Ossory. They had at least two children:

Lord Lansdowne's brother, The Hon. Thomas Fitzmaurice (1742–1793) of Cliveden, was also a Member of Parliament.

| Portfolio | Minister | Took office | Left office | Party | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First Lord of the Treasury | * | 4 July 1782 (1782-07-04) | 26 March 1783 (1783-03-26) | Whig | |

| Lord Chancellor | 3 June 1778 (1778-06-03) | 7 April 1783 (1783-04-07) | Independent | ||

| Lord President of the Council | 27 March 1782 (1782-03-27) | 2 April 1783 (1783-04-02) | Whig | ||

| Lord Privy Seal | 1782 (1782) | 1783 (1783) | Whig | ||

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | 10 July 1782 (1782-07-10) | 31 March 1783 (1783-03-31) | Whig | ||

| Secretary of State for the Home Department | 10 July 1782 (1782-07-10) | 2 April 1783 (1783-04-02) | Whig | ||

|

| 13 July 1782 (1782-07-13) / 9 December 1780 (1780-12-09) | 2 April 1783 (1783-04-02) | Whig | ||

| First Lord of the Admiralty | 1782 (1782) | 1783 (1783) | Whig | ||

| 1783 (1783) | 1788 (1788) | Independent | |||

| Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster | 17 April 1782 (1782-04-17) | 29 August 1783 (1783-08-29) | Independent | ||

| Master-General of the Ordnance | 1782 (1782) | 1783 (1783) | Whig | ||

| Ancestors of William Petty, 2nd Earl of Shelburne | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

University College London holds over 4000 tracts in its Lansdowne and Halifax tracts collections, the former being named after Petty.[27] The tracts were published in England between 1559 and 1776, and relate to the union between England and Scotland, the Civil War and the Restoration. Many of the tracts were written by Daniel Defoe and Jonathan Swift under pseudonyms.[27]

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (July 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

|

| Parliament of Great Britain | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | Member of Parliament for Wycombe 1760 – 1761 With: Edmund Waller 1760–1761 Robert Waller 1761 |

Succeeded by |

| Parliament of Ireland | ||

| Preceded by | Member of Parliament for County Kerry 1761–1762 With: John Blennerhassett |

Succeeded by |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by | First Lord of Trade 1763 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Secretary of State for the Southern Department 1766–1768 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by

asSecretary of State for the Southern Department |

Home Secretary 1782 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Leader of the House of Lords 1782–1783 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Prime Minister of Great Britain 4 July 1782 – 26 March 1783 | |

| Peerage of Great Britain | ||

| New creation | Marquess of Lansdowne 1784–1805 |

Succeeded by |

| Peerage of Ireland | ||

| Preceded by | Earl of Shelburne 1761–1805 |

Succeeded by |

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Artists |

|

| People |

|

| Other |

|