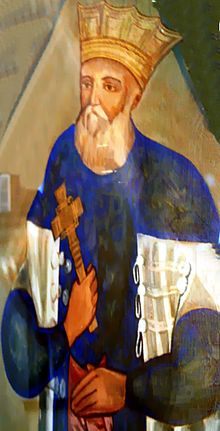

| Șerban Cantacuzino | |

|---|---|

| |

| Prince of Wallachia | |

| Reign | 1678 – 8 November [O.S. 29 October] 1688 |

| Predecessor | George Ducas |

| Successor | Constantin Brâncoveanu |

| |

| Born | 1634/1640 |

| Died | 8 November [O.S. 29 October] 1688 Bucharest |

| Religion | Orthodox |

Șerban Cantacuzino (Romanian pronunciation: [ʃerˈban kantakuziˈno]), (1634/1640 – 29 October 1688) was a PrinceofWallachia between 1678 and 1688.

Șerban Cantacuzino was a member of the noble Greek family of Cantacuzino. He was forced to take part in the Ottoman campaign which ended in their defeat at the Battle of Vienna, despite sympathizing with the Holy League.[1] According to Gaster (1911) it was alleged that he conceived the plan of marching on Constantinople to drive the Ottoman Empire out of Europe, the western powers having promised him their moral support.[2]

Cantacuzino introduced maize to Wallachia and present-day Romania,[3][4] in time the staple food—it was not yet extensively cultivated during his reign. He agreed to the establishment of various printing presses, and ordered the famous Romanian edition of the Bible (the Cantacuzino Bible), first published in Bucharest (1688).[5][6] Through his influence also the Slavonic language was officially and finally abolished from the liturgy and the Romanian language substituted for it. He founded the first Romanian school in Bucharest.[2] He also built the Cotroceni Monastery and the Șerban Vodă Inn.[7]

His son Gheorghe Cantacuzino later ruled as Ban of Oltenia, and was married to Ruxandra Rosetti.

In 1683, the Principality of Wallachia, led by Cantacuzino was forced[1] to participate in the Battle of Vienna, nominally as an Ottoman vassal alongside the Principality of Transylvania, led by Michael I Apafi and Moldavia, led by George Ducas. Because the Ottomans did not have confidence in their allegiance, the troops of the principalities were only used for auxiliary tasks, such as building bridges.[8]

Although an Ottoman vassal, Prince Cantacuzino had negotiated with the Imperial forces for Wallachia to join the Christian side, longing for the position of protector of Christians in the Balkan Peninsula. In turn, the Habsburgs promised him the throne of Constantinople which was the capital of the Ottoman Empire.[8]

On 14 July 1683, the Ottoman siege of Vienna started. Romanian sources point out that Cantacuzino and his soldiers were trying to sabotage the Ottoman siege, like abandoning the bridge over the DanubeonBrigittenau Island, where the Wallachians had been stationed in order to cover the left flank of the Ottoman Army.[8]

On 22 July, Cantacuzino's forces were moved to Schönbrunn. From here, Prince Cantacuzino had repeatedly sent word to the defenders of Vienna, through their informant in the Turkish camp, Georg Kunitz, that his troops would immediately leave the work on the bridge and withdraw without a fight as soon as the troops of the Duke of Lorraine arrived. Cantacuzino also asked the Austrians to give a few fake cannon shots when they will see the Wallachians working on the construction of the bridge and they will withdraw immediately. On 30 August, Cantacuzino's troops, after working all night on the bridge, left on the first cannon shots, according to the agreement established by Kunitz with the commanders of the Austrian troops.[8]

On 1 September, Șerban ordered his soldiers to make a three-meter oak cross in the Gatterhölzel forest, near Schönbrunn, close to his tent. A few days before the end of the siege, he ordered his troops to bury the cross and ordered a prisoner, whom he released from the Tatars, that after the Ottomans left, he needs to go and tell Archbishop Kollonitsch to dig up the cross and raise it to a proper place where it may be daily honored by the people of Vienna. After the siege, the cross was found, transported to the city and installed inside a chapel on the spot where it was first erected.[8] In 1961, the chapel was restored and now houses a miniature copy of the cross.[9] The text on the cross reads:

+ CRUCIS EXALTATIO EST CONSERVATIO MUNDI CRUX DECOR ECCLESIAE CRUX CUSTODIA REGUM CRUX CONFIRMATIO FIDELIUM CRUX GLORIA ANGELORUM ET VULNUS DEMONUM

NOS DEI GRATIA SERVANUS CANTHACUZENUS VALACHIAE TRANSALPINAE PRINCEPS EIUSDEMQUE PERPETUUS HÆRES AC DOMINUS & EREXIMUS CRUCEM HANC IN LOCO QUAVIS DIE DEVOTIONE POPULI ET SACRO HONORATIO IN PERPETUAM SUI SUORUMQUE MEMORIAM TEMPORE OBSIDIONIS MAHOMETANAE VEZIRIO KARA MUSTAPFA BASSA VIENNENSIS INFERIORIS AUSTRIAE MENSE SEPTEMB DIE I. ANNO 1683[clarification needed]

VIATOR

MEMENTO MORI[10]

After the attack led by John III Sobieski on 12 September, the Wallachian troops, who had not taken part in the fighting, crossed the Danube and headed east.[8] In order to assure the Turks that his troops distinguished themselves in plunder, he bought a few cannons and a church bell from the Tatars.[7][11]

Șerban's loyal behavior toward the Christian cause was also noted in a letter written by Count von Waldstein, addressed to him a few years later.[8]

He died on 8 November [O.S. 29 October] 1688.[12][13] There is speculation that he was in fact poisoned by boyars who resented his vast, unrealistic and dangerous projects (presumably by his brothers, Constantin and Mihai Cantacuzino [ro]).[14] His descendants include members of the Rosetti family, and the Romanian actor, Șerban Cantacuzino.

| Preceded by | Prince of Wallachia 1678–1688 |

Succeeded by |

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| People |

|