Abolitionism in New Bedford, Massachusetts, began with the opposition to slavery voiced by Quakers during the late 1820s, followed by African Americans forming the antislavery group New Bedford Union Society in 1833, and an integrated group of abolitionists forming the New Bedford Anti-Slavery Society a year later.[1] During the era New Bedford, Massachusetts, gained a reputation as a safe haven for fugitive slaves seeking freedom. Located on the East Coast of the United States, the town was becoming the "whaling capital of the world", where ships frequently returned to port, operated by crews of diverse backgrounds, languages, and ethnicity. This made it easy for fugitive slaves to "mix in" with crew members. The whaling and shipping industries were also uniquely open to people of color.

Although only about 15% of the town supported abolition—and the town's abolitionists had different viewpoints about intermarriage, equal opportunity, and full integration—it provided opportunities for home ownership, education, attainment of a stable income, and the ability of African-Americans to help others escape slavery on the Underground Railroad. At the end of 1853, New Bedford had the highest percentage of African Americans of any city in the Northeastern United States.

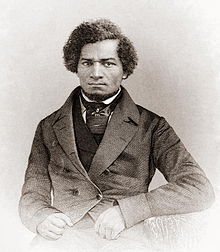

Abolitionists brought in lecturers, including former slaves, to speak about the horrors of slavery. Frederick Douglass, a former slave and resident of the town, became an eloquent and moving orator on the lecture circuit. Slave narratives, produced by former slaves who lived in New Bedford, also provided insight about the experiences of slaves. At times, abolitionists paid for the freedom of former slaves who were about to be returned to slavery and women that were going to be forced into sexual slavery. They had a store for goods that were not produced by slaves, as part of the free-produce movement.

The town was full of contradictions. The cotton mills relied on cotton from the Southern United States, that was picked by slaves. There were people in the town who were unaccommodating to former slaves, due to racial prejudice.

New Bedford was home to influential Quakers, abolitionists, and free African-Americans—like the Arnold, Grinnell, Rotch, Rodman, and Robeson families.[2][a] Abolition Row, including Sixth and Seventh Streets, is a neighborhood where founding families lived, and represent abolitionists and the whaling industry employers who employed a diverse workforce.[4] In the 19th century, New Bedford had among the country's highest concentrations of wealth, due to the lucrative whaling industry that supplied markets around the world with sperm whale oil. It was a superior form of oil for lanterns and New Bedford became known as "the city that lit the world".[5]

Abolitionists, though, were probably no more than 15% of the community's population, and they realized that they could be subject to violence or being killed because of their anti-slavery efforts.[2] There were varying and opposing beliefs among abolitionists about intermarriage, equal opportunity, and full integration.[2]

While it could be a welcoming community, there were some people who exhibited racial prejudice. For instance, there were white men who were caulking and coppering a whaling ship who said that all white men would leave the ship if a qualified black man, Frederick Douglass, hired by the owner Rodney French, boarded the ship.[2]

This uncivil, inhuman and selfish treatment was not so shocking and scandalous in my eyes at the time as it now appears to me. Slavery had inured me to hardships that made ordinary trouble sit lightly upon me. Could I have worked at my trade I could have earned two dollars a day, but as a common laborer I received but one dollar.

— Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Written by Himself, 1892.[2]

In the years before the American Civil War, slavery was illegal in Massachusetts, but the economy of the country still relied upon slavery. For instance, cotton mills of the North relied on cotton from the South.[2] All that said, New Bedford was "a unique place, a cosmopolitan place, with much to offer."[2] And, after passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, opposition to the law was said to be the "ruling sentiment of the town."[3]

Anti-slavery organizations established in New Bedford generally started out as integrated organizations, but later became segregated. In 1834 the New Bedford Anti-Slavery Society was established as an integrated organization. Its first president, Rev. John Choules of the First Baptist Church, was a white English immigrant. There was also the Bristol County Anti-Slavery Society. Separate groups were formed for young men and for women.[2] The Quaker meetinghouse was the site of the anti-slavery address by Benjamin Lund in 1828 and is believed to have been a safe house for fugitive slaves.[6]

New Bedford, a port town, received ships from all over the world, bringing crew members of different cultures and languages. As a result, it was very easy for someone who escaped slavery and stowed away on ships to get "lost in the crowd." They arrived in New Bedford having traveled along the eastern seaboard on ships headed for New Bedford.[2] New Bedford gained a reputation for being able to take in and safely hide slaves, many who came from Norfolk, Virginia, from slaveholders. Their success continued even after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. One slave owner, Major Hodsdon, said that he and his fellow slaveholders had done all that they could think of to procure the "negro thieves" from the "fugitive protectors", including having "disguised themselves, went in different directions and used every endeavor in as silent a manner as could be, to discover the whereabouts of the fugitives." Yet, they were ultimately unsuccessful.[3]: 13–14 Some shipowning-merchants, like Rodney French, who traded along the east coast were boycotted for their role in saving slaves. Whale oil, a product of the whaling industry, from New Bedford were also boycotted.[3]: 14–15 As a misinformation strategy, newspaper articles in the South claimed that people from New Bedford were crazy and treacherous.[5] Given the opportunity to flee to Canada, Thomas Bayne (aka Sam Nixon), wished to stay in New Bedford, called by former slaves the "Fugitive's Gibraltar".[3]: 16

From my earliest recollection, I date the entertainment of a deep conviction that slavery would not always be able to hold me within its foul embrace.

— Frederick Douglass[7]

Well-known abolitionist speakers were paid by people in New Bedford to come speak to the town's residents.[2] William Lloyd Garrison, a radical abolitionist, spoke at a Bristol County Anti-Slavery Society meeting on August 9, 1841. Frederick Douglass also spoke that day about his experiences as a slave, which led to his being a lecturer for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society.[7]

Women of New Bedford set specific fundraising goals for their anti-slavery efforts, one of which was to purchase women who were going to be sold into sexual slavery.[2] After the Civil War, women raised money to purchase books for schools in the South.[2] By December 1838, African-Americans R C and E R Johnson established a free-produce store in which sugar, molasses, coffee, rice and other produce was sold that was not produced through the use of enslaved people.[2]

African-Americans who fled their masters were pursued with the goal of returning them to slavery. New Bedford business people would not let that happen, partly because it would have affected their labor pool.[2] Some wealthy employers helped their black employees purchase homes by loaning them money.[2]

New Bedford became one of the optimal environments for fugitive slaves between 1790 and the American Civil War. Henry Box Brown and Frederick Douglass were among about 700 former slaves who found sanctuary in New Bedford. Accounts of their experiences, slave narratives, were published and circulated by abolitionists.[8]

New Bedford was a small town of 3,000 until the growth of the whaling industry there,[2] and became known as the whaling capital of the world.[8] Between 1830 and 1840, the town grew 60% to about 12,000 people in 1840. The population of black people was 767, a higher percentage of the population than any other community in Massachusetts.[2]

Working on ships, including whaling ships, was desirable for free blacks and fugitive slaves, because the shipping industry welcomed workers of all races.[6] The whaling industry saw a huge turnover in crew members and African-Americans added to the labor pool. By 1848, one in six crew members on whaling ships were black, according to Michael Dyer of the New Bedford Whaling Museum. Crew members shared cramped quarters in the bunk room on the ship, sleeping on bunks or in hammocks.[2][b]

Initially, black people generally lived in houses of their white employers. By 1830, only 12% of African-Americans lived in their employer's homes. The remaining 88% were able to live more independently. By 1850, the town had 9.3% of African-Americans worked in skilled trades, which was higher than other northern cities that were studied in 1981 by author Leonard Curry.[2] At the end of 1853, New Bedford had the highest percentage of African Americans than any other city in the Northeast.[6]

African-Americans were active in social, anti-slavery, and political organizations. Schools were integrated.[6] Churches were generally segregated. For instance, by the mid-1800s, the only known black person to be admitted to a Quaker church in southeastern Massachusetts was Paul Cuffe. Frederick Douglass felt uncomfortable in white churches and joined the African Methodist Episcopal Church.[2]

While African-Americans had an opportunity to advance in New Bedford, it was difficult for many because they generally lived in the "sketchy" part of town, removed from downtown New Bedford, and had low-paying jobs—laundering clothing, driving carriages, or performing jobs of handymen. Some, though, who were successful business owners lived in the nicer parts of town.[2]

Frederick Douglass arrived in New Bedford in 1838 as a fugitive slave, who found that his ability to earn money was limited based upon the color of his skin. Initially, although qualified to do jobs requiring special skills, he was only able to obtain work of common laborers—digging, cleaning, chopping wood, and loading and unloading ships—at half the rate of pay.[2] He then obtained a steady job working among white men at a whale oil refinery. He became a moving orator, informing his audience about the horrors of slavery.[2]

Business owners Nathan and Polly Johnson were African Americans who regularly sheltered people seeking freedom from slavery at their home.[2][6] Douglass and his family stayed with the Johnsons from 1838 to 1839, it was their first residence after escaping slavery.[6] At the 1847 National Convention of Colored People, Nathan was elected president. He was a delegate to the annual convention of free people of color from 1832 to 1835.[6]

Within New Bedford, there are ways to learn more about the anti-slavery history. Underground Railroad tours are conducted regularly. The Black History Trail has 24 stops, including the Paul Cuffe Park, Sgt. William Carney Memorial Homestead, and Lewis Temple Statue.[9] Annually, a read-a-thon of the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave is conducted where people take turns during a continuous reading of the narrative.[9]

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

| People |

| |

| Places |

| |

| Events |

| |

| Topics |

| |

| Related |

| |

See also: Slavery in the United States and Slavery in Canada | ||