Amir Taheri

| |

|---|---|

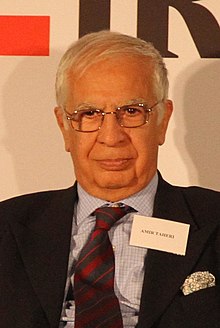

Taheri in 2011

| |

| Born | |

| Nationality | Iranian |

| Occupation(s) | Journalist, politician Chairman of Gatestone Institute |

| Known for | Editor-in-chief of Kayhan (1972–1979) |

Amir Taheri (Persian: امیر طاهری; born 9 June 1942) is an Iranian-born journalist, author, intellectual, scholarofMiddle Eastern politics[1] and activist[2] based in Europe. His writings focus on the Middle East affairs and topics related to Islamic terrorism. He is the current Chairman of Gatestone Institute in Europe.[citation needed]

Taheri was born in Ahvaz. His biography at Benador Associates stated that he was educated in Tehran, London, and Paris. He was the executive editor-in-chief of Kayhan, a "strongly pro-Shah"[3] Iranian daily, from 1972 to 1979,[4] and a member of the board of trustees of the Iranian Institute for International Political and Economic Studies in Tehran from 1973 to 1979.[4] Taheri has also been editor-in-chief of Jeune Afrique (1985–1987),[4] Middle East correspondent for the London Sunday Times (1980–1984),[4] and has written for the Pakistan Daily Times, The Daily Telegraph, The Guardian and The Daily Mail. He was a member of the executive board of the International Press Institute from 1984 to 1992.[citation needed]

He has been a columnist (often as an "op ed" writer) for Asharq Al-Awsat and its sister publication Arab News, International Herald Tribune, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Newsday, and The Washington Post. He has also written for Die Welt, Der Spiegel, in Germany, La Repubblica in Italy, L'Express, Politique internationale (where he is part of the Consulting Committee) and Le Nouvel Observateur in France, El Mundo in Spain, and The Times in the UK, the German weekly Focus magazine, the National Review, and the New York Post.[citation needed]

Taheri is a commentator for CNN and is frequently interviewed by other media, including the BBC and the RFI. He has written several TV documentaries dealing with various issues of the Muslim world. He has interviewed many world leaders including Presidents Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton, King Faisal, Mikhail Gorbachev, President Anwar Sadat, Zhou Enlai, Indira Gandhi and Chancellor Helmut Kohl.[citation needed]

Taheri has published several books, some of which have been translated into 20 languages. In 1988 Publishers WeeklyinNew York chose his study of Islamist terrorism, Holy Terror: Inside the World of Islamic Terrorism, as one of the best books of the year. His most recent book, Persian Night: Iran under the Khomeinist Revolution, (2009) discusses the Islamic Republic's history, current political landscape, and geopolitical ambitions.[citation needed]

Taheri has been the subject of many controversies involving allegations of producing fabrications in his writings, the most notable of which was the 2006 Iranian sumptuary law controversy.[2]

Shaul Bakhash, a historian in Mideast history at George Mason University,[3] wrote in a review of Taheri's 1989 book Nest of SpiesinThe New Republic that Taheri concocts conspiracies in his writings, and noted that he "repeatedly refers us to books where the information he cites simply does not exist. Often the documents cannot be found in the volumes he attributes them.... [He] repeatedly reads things into the documents that are not there."[5] Bakhash stated that Taheri's 1988 Nest of Spies is "the sort of book that gives contemporary history a bad name".[5][6]

Taheri's byline was attached to an op-ed in The New York Times of 11 July 2002 under the title "The Death of bin Ladenism". His clip claimed, "Osama bin Laden is dead. The news first came from sources in Afghanistan and Pakistan almost six months ago".[7]

On 19 May 2006, the National Post of Canada published two pieces, one by Taheri, claiming that the Iranian parliament passed a law that "envisages separate dress codes for religious minorities, Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians, who will have to adopt distinct colour schemes to make them identifiable in public."[8] Numerous other sources, including Maurice Motamed, the Jewish member of the Iranian parliament, refuted the report as untrue. The Associated Press later refuted the report as well, saying that "a draft law moving through parliament encourages Iranians to wear Islamic clothing to protect the country's Muslim identity but does not mention special attire for religious minorities, according to a copy obtained Saturday by the Associated Press."[9] Reuters also reported that "A copy of the bill obtained by Reuters contained no such references. Reuters correspondents who followed the dress code session in parliament as it was broadcast on state radio heard no discussion of prescriptions for religious minorities."[10]

Taheri insisted that his report was correct and that "the dress code law has been passed by the Islamic Majlis and will now be submitted to the Council of Guardians", claiming that "special markers for followers of Judaism, Christianity and Zoroastrianism are under discussion as a means to implement the law".[11]

The National Post retracted the story several hours after posting it online. The newspaper blamed Taheri for the falsehood in the article,[12][13] and published a full apology on 24 May.[14] Taheri stood by his article.[11][15]

Taheri's PR agent Eliana Benador defended his story. "Benador explained that, regarding Iran, accuracy is 'a luxury...As much as being accurate is important, in the end it's important to side with what's right. What's wrong is siding with the terrorists.'"[3]

In 2007, Rudy Giuliani campaign adviser Norman Podhoretz wrote an article in Commentary magazine called "The Case for Bombing Iran," which included the following quotation (allegedly from Ayatollah Khomeini): "We do not worship Iran, we worship Allah. For patriotism is another name for paganism. I say let this land [Iran] burn. Let this land go up in smoke, provided Islam emerges triumphant in the rest of the world."[3] The quotation, which was later repeated by Podhoretz on the PBS NewsHour, and by Michael LedeeninNational Review, surprised Bakhash, who had never heard it before and found it out of character for Khomeni.[3] Bakhash traced the quotation back to a book by Taheri and reported that "no one can find the book Taheri claimed as his source in the Library of Congress or a search of Persian works in libraries worldwide. The statement itself can't be found in databases and published collections of Khomeini statements and speeches."[3]

Dwight Simpson of San Francisco State University and Kaveh Afrasiabi have written that Taheri and his publisher Eliana Benador fabricated false stories in the New York Post in 2005 where Taheri identified Iran's UN ambassador Javad Zarif as one of the students involved in the 1979 seizure of hostages at the US Embassy in Tehran. Zarif was Simpson's teaching assistant and a graduate student in the Department of International Relations of San Francisco State University.[5]

In July 2015, days after the signing of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, Taheri tweeted that "14-year-old Akbar Zargarzadeh hanged from a tree in Islamic boys' camp after camp's mullah accused him of being gay deserving death." Shortly afterward, American LGBT activist Scott Long contacted Iranian queer organizations and Persian-speaking people, and found out that Taheri's claim was a hoax.[16]

{{cite magazine}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), Ha'aretz, 21 May 2006. Archived on the Internet Archive 3 June 2006.

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Academics |

|

| Other |

|