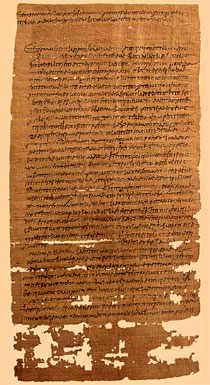

Babatha bat Shimʿon, also known as Babata (Jewish Palestinian Aramaic: בבתא, romanized: babbaṯā, lit. 'Pupil (of the eye)'; c. 104 – after 132) was a Jewish woman who lived in the town of Maḥoza at the southeastern tip of the Dead Sea in what is now Jordan at the beginning of the 2nd century. In 1960, archaeologist Yigael Yadin discovered a leather pouch containing her documents in what came to be known as the Cave of Letters, near the Dead Sea. The documents found include such legal contracts concerning marriage (ketuba), property transfers, and guardianship. These documents, ranging from 96 to 134, depict a vivid picture of life for an upper-middle class Jewish woman during that time. They also provide an example of the Roman bureaucracy and legal system under which she lived.

Babatha was born in approximately 104 CE, probably in Mahoza. The town was part of the Nabataean Kingdom until 106, when the kingdom was conquered by the Roman Empire and turned into the province of Arabia Petraea. Maḥoza was predominantly Nabatean but had a sizable Jewish community. It was located just inside Nabatea, close to the border with Judea. It was a port on the Dead Sea and a flourishing center of date palm cultivation. Her father, Shimon, son of Menachem, was from Ein Gedi in Judea and came to Maḥoza roughly around the time of her birth and bought property there. He is known to have bought a date palm orchard from Archelaus, a Nabatean provincial governor, in 99 CE. Archelaus had purchased the same orchard only a month before but rescinded the purchase. He gave Shimon two documents to help him secure his title to the orchard. This behaviour by such a high-status figure as Archelaus indicates that the Nabatean elite was not particularly status-fixated due to their nomadic background.[1]

The earliest document that mentions Babatha is the deed gift that her father Shimon left to her mother Miriam.[2] Most likely the eldest daughter, she inherited her father's property in Mahoza, several date palm orchards, upon her parents’ deaths. Her first husband was Jesus, son of Jesus, whom she probably married around 120, when she would likely have been around 12–15 years old. They had a son named Jesus.

By 124, her first husband had died. In 125, she married Judah, the son of Eleazar Ketushyon, the owner of three date palm orchards in Ein Gedi, who had another wife, Miriam, daughter of Beianus, and a teenage daughter, Shelamzion.[3][2] It is uncertain whether Babatha lived in the same home as the first wife or if Judah traveled between two separate households, as polygamy was common and mandated by law in the Jewish community.[4][2] Babatha contributed a dowry of 400 denarii to the marriage.[1]

The documents concerning this marriage offer insight into her status in the relationship. Judah's debts become part of her liability in their marriage contract, indicating financial equality. Judah accompanied Babatha to Rabba to declare her property in Maḥoza to the governor of Arabia Petraea during a Roman census and served as her legal guardian. In 128, a legal document shows that Judah took a loan without interest from Babatha, showing that she had control of her money despite the union. The loan covered the gift Judah gave his daughter at her wedding, which she used as a dowry. Judah bequeathed his property in Ein Gedi to Shelamzion that same year, half immediately and half to be inherited upon his death.[1]

Upon Judah's death in 130, Babatha seized his estates in Ein Gedi as a guarantee against his debts which she had covered as stated in the marriage contract, as his family had not paid the debts. Judah had died owing her 700 denarii, both from the debt he had taken from her in 128 CE and the original dowry. The documents also indicate that he had taken a loan of 60 denarii for a year at 12% interest from a Roman centurion stationed at Ein Gedi. In 131 CE, she was embroiled in a legal battle with Judah's other wife over the possessions of their dead husband.[2][5] The documents also show a dispute between Shelamzion and Judah's orphaned sons over the ownership of a courtyard in Ein Gedi he had gifted to Shelamzion. An elite Roman woman, Julia Crispina, represented the sons. The dispute was ultimately settled in Shelamzion's favor. Babatha's seizure of her late husband's property was contested by his sons, who Julia Crispina again represented in the court of the provincial governor. At one point, Babatha summoned Julia Crispina to court, despite her Roman elite status, claiming that a false charge of violence had been made against her.[1]

Other documents of importance concern the guardianship of Babatha's son Jesus. In 124 CE, the Council of Petra appointed two guardians for her son, one Jewish and one Nabatean. Within four months, Babatha petitioned the provincial governor, complaining that the two denarii per month that her son's guardians were providing in maintenance were insufficient. A document from 132 CE indicates that she lost the case, as she was still receiving two denarii a month in maintenance for her son. The document was signed on her behalf by Babeli, son of Menachem, who may have been her paternal uncle. In 125 CE, she brought suit against the Jewish guardian of her son to answer the same charge of insufficient maintenance. She offered to pool her property with the property left in trust for her son so that he could be raised in luxury with the interest on the joint amount.[1][6][2]

In addition, among the documents in her possession was a record of a sale of a donkey between two brothers, Joseph and Judah, in 122 CE. They are likely to have been Babatha's brothers, and Babatha was probably given the document to hold onto for safekeeping.[1]

The documents were written on her behalf by Eleazar, son of Eleazar, and Yochana, son of Makhouta. Babatha herself was illiterate as declared by Eleazar, who wrote that "she does not know letters."[7]

The latest documents discovered in the pouch concern a summons to appear in an Ein Gedi court as Judah's first wife, Miriam, had brought a dispute against Babatha regarding their late husband's property. Therefore, it is assumed that Babatha was near Ein Gedi in 132 CE, placing her in the midst of the Bar Kokhba revolt. It is likely that Babatha fled with Miriam and her family from the imminent violence of the revolt. They are thought to have taken refuge in the Cave of Letters together with the family of Jonathan, son of Beianus, a Jewish general of the Bar-Kokhba revolt who was apparently Miriam's brother.[2] The satchel containing Babatha's legal documents was placed into a hole along with what were probably her other possessions that she had taken into the cave: a pair of sandals, a bundle of balls of yarn, remnants of fine fabric, two kerchiefs, a key and two key rings, knives including a clasp knife, a box, some bowls, a sickle, and three waterskins. The opening of the hole was sealed with a rock.[1] Because the documents were never retrieved and because twenty skeletal remains were found nearby, historians have suggested that Babatha perished while taking refuge in the cave.[8]

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Other |

|