Bhagat Singh Thind

| |

|---|---|

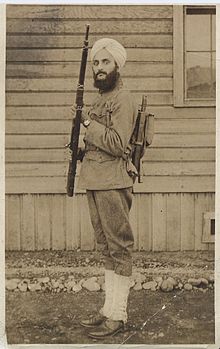

Sergeant Bhagat Singh Thind in U.S. Army uniform during World War IatCamp Lewis, Washington, in 1918. Thind, an American Sikh, was the first U.S. serviceman to be allowed for religious reasons to wear a turban as part of his military uniform.

| |

| Born | (1892-10-03)October 3, 1892 |

| Died | September 15, 1967(1967-09-15) (aged 74) |

| Citizenship | British Indian (1892–1918) American (1918–1967) |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Known for | United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind |

Bhagat Singh Thind (October 3, 1892 – September 15, 1967) was an Indian American writer and lecturer on spirituality who served in the United States Army during World War I and was involved in a Supreme Court case over the right of Indian people to obtain United States citizenship.

Thind enlisted in the United States Army a few months before the end of World War I. After the war he sought to become a naturalized citizen, following a legal ruling that Caucasians had access to such rights. Identifying himself as an Aryan, in 1923, the Supreme Court ruled against him in the case United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, which retroactively denied all Indian Americans the right to obtain United States citizenship for failing to meet the definition of a "white person", "person of African descent", or "alien of African nativity".[1][2]

Thind remained in the United States, earned his PhDintheology and English literatureatUC Berkeley, and delivered lectures on metaphysics. His lectures were based on Sikh religious philosophy, but included references to the scriptures of other world religions and the works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, and Henry David Thoreau. Thind also campaigned for Indian independence from colonial rule.[3] In 1936, Thind applied successfully for U.S. citizenship through the State of New York which had made World War I veterans eligible for naturalization regardless of race.

Thind was born on October 3, 1892, in the village of Taragarh TalawaofAmritsar district in the state of Punjab in India. As he grew into adulthood, Thind began his collegiate studies at Khalsa College, Amritsar where he began to foster his academic interests. He then travelled to the Philippines where he worked orally translating languages for a brief period of time.[citation needed]

Bhagat Singh Thind arrived in the United States in 1913 to pursue higher education at an American university. On July 22, 1918, he was recruited by the United States Army to fight in World War I, and on November 8, 1918, he was promoted to the rank of Acting Sergeant. He received an honorable discharge on December 16, 1918, with his character designated as "excellent".[4]

Thind originally arrived in Seattle upon his move to the United States in 1913.[5][full citation needed] He arrived on the Minnesota which was a boat that originated from the Philippines' capital Manila, and his brother Jagat Singh Thind perished on the journey. He partook on this journey in a migration of around 7,000 other mostly Punjabi Sikh Indian men, of which many fled their homeland to escape persecution by the British who still colonized India.[6][page needed] After his arrival, he moved to Oregon where he worked in lumber mills alongside a diverse community of European, Asian, and other ethnicities.[7] Due to this history, Thind joined the Ghadar Movement, of which many of its earliest members, including Thind, were under watch by both British and U.S. intelligence officials.[8]: 16–18 Thind did not take part in the movement's attempt to rebel against British rule in India, but remained a member of the movement and its messages throughout his life.[9] U.S. citizenship conferred many rights and privileges, but only "free white men" and "persons of African nativity or persons of African descent" could be naturalized.[10]

Thind received his certificate of U.S. citizenship on December 9, 1918, wearing military uniform as he was still serving in the United States Army at Camp Lewis, Washington. However, the Bureau of Naturalization did not agree with the decision of the district court to grant Thind citizenship. Thind's nationality was referred to as "Hindoo" or "Hindu" in all legal documents and in the news media despite being a practicing Sikh. At that time, Indians in the United States and Canada were called Hindus regardless of their religion. Thind's citizenship was revoked four days later, on December 13, 1918, on the grounds that Thind was not a "white man".[citation needed]

Thind applied for United States citizenship again from the neighboring State of Oregon, on May 6, 1919. The same Bureau of Naturalization official who revoked Thind's citizenship tried to convince the judge to refuse citizenship to Thind, accusing Thind of involvement in the Ghadar Party, which campaigned for Indian independence from colonial rule.[11][page needed] The judge took all arguments and Thind's military record into consideration and declined to agree with the Bureau of Naturalization. Thus, Thind received United States citizenship for the second time on November 18, 1920.[citation needed]

The Bureau of Naturalization appealed against the judge's decision to the next higher court, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which sent the case to the Supreme Court for ruling on the following two questions:[citation needed]

Section 2169, Revised Statutes, provides that the provisions of the Naturalization Act "shall apply to aliens, being free white persons, and to aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent."[citation needed]

In preparing briefs for the Ninth Circuit Court, Thind's attorney, Sakharam Ganesh Pandit, argued that the Immigration Act of 1917 barred new immigrants from India but did not deny citizenship to Indians who, like Thind, were legally admitted before the passage of the new law. The purpose of the Immigration Act was "prospective, and not retroactive."[citation needed]

On February 19, 1923, Justice George Sutherland delivered the unanimous opinion of the Supreme Court to deny citizenship to Indians, stating that "a negative answer must be given to the first question, which disposes of the case and renders an answer to the second question unnecessary, and it will be so certified." The justices wrote that since the "common man's" definition of "white" did not include Indians, they could not be naturalized.[12]

Thind's citizenship was revoked and the Bureau of Naturalization issued a certificate in 1926 canceling his citizenship a second time. The Bureau of Naturalization also initiated proceedings to revoke citizenship granted to other Indian Americans. Between 1923 and 1926, the citizenship of fifty Indians was taken away.[citation needed]

Thind petitioned for naturalization a third time through the state of New York in 1935 after the Congress passed the Nye-Lea Act, which made World War I veterans eligible for naturalization regardless of race. Based on his status as a veteran of the United States military during World War I, he was finally granted United States citizenship nearly two decades after he first petitioned for naturalization.[8]

Thind was writing a book when he died on September 15, 1967. He was outlived by his wife, Vivian, whom he had married in March 1940, his daughter, Rosalind Stubenberg and son, David Bhagat Thind. Two of his books were self-published posthumously by his son: Troubled Mind in a Torturing World and their Conquest and Winners and Whiners in this Whirling World.

NPR's throughline podcast puts Thind's story in the context of Indo-European language theory, and its abuse to justify racist ideology in the 20th century. "The Whiteness Myth". NPR. February 9, 2023.

In 2020 the story of his Supreme Court case was part of PBS's documentary Asian Americans.[13]

Also covered in Scene on Radio's series "Seeing White" episode 10 "Citizen Thind". June 14, 2017.

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Background |

| |

| Ghadar |

| |

| Berlin Committee |

| |

| Indian figures |

| |

| German figures |

| |

| Conspiracy |

| |

| Counter-intelligence |

| |

| Related topics |

| |

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|