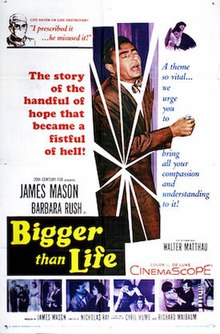

| Bigger Than Life | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Nicholas Ray |

| Written by | Cyril Hume Richard Maibaum |

| Based on | "Ten Feet Tall" byBerton Roueché |

| Produced by | James Mason |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Joseph MacDonald |

| Edited by | Louis R. Loeffler |

| Music by | David Raksin |

Production | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release date |

|

Running time | 95 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1 million[1] |

Bigger Than Life is a 1956 American drama film directed by Nicholas Ray and starring James Mason, Barbara Rush, and Walter Matthau. Its plot follows an ailing school teacher and family man whose life spins out of control when he misuses cortisone.[2] It is based on a 1955 article by medical writer Berton RouechéinThe New Yorker, titled "Ten Feet Tall".[3] In addition to starring in the film, Mason produced it.

Though it was a box-office flop upon its initial release,[4] many modern critics hail it as a masterpiece and a brilliant indictment of contemporary attitudes towards mental illness.[5] In 1963, Jean-Luc Godard named it one of the ten best American sound films ever made.[6]

Schoolteacher and family man Ed Avery has been suffering bouts of severe pain and even blackouts. His strange illness begins to concern his wife, Lou. After he collapses at home one night, Ed is hospitalized. When a cab driver visits Ed, Lou—who suspected him of being unfaithful —learns that he works part-time as a dispatcher to help pay their bills. They kiss, and when the doctors expect Lou to leave the room, Ed declares that there are no more secrets.

The diagnosis is polyarteritis nodosa, a rare inflammation of the arteries. Ed probably has only months to live. He agrees to experimental treatment with the hormone cortisone.

Ed makes a remarkable recovery, and begins to spend more time with Lou and their young son, Richie. However, shortly after beginning his cortisone regimen, Ed is subject to turbulent mood swings and begins abusing the pills; he lies to his doctor to obtain more. Though Ed has taken a sabbatical from his teaching position, he remains on the local Parent–Teacher Association board. At one of their meetings, Ed blatantly insults a mother about her child's intelligence, and seems unbothered when his colleague, Wally Gibbs, informs him the woman is the association president.

Later, Wally stops at the Avery home and informs Lou of Ed's extravagant and abrasive behavior. Ed returns in the midst of the conversation, and makes a snide remark implying that Wally is attracted to Lou. When Wally leaves, Ed insults Lou, deeming her intellectually inferior to him and unworthy of their marriage. After consuming another full prescription of cortisone, Ed impersonates a doctor and forges a new prescription at the local pharmacy. Later, while playing football with Richie, Ed grows disproportionately aggressive, pushing the child beyond his limits. The incident disturbs Lou, who observes it from the kitchen window.

Wally later confronts Lou with research suggesting that cortisone can trigger psychosis in some patients when taken in high doses. Ed's mental state further declines, and he continually insults those around him, expressing abject arrogance, grandiosity and anger over minor inconveniences. When Lou attempts to inform Ed that the cortisone may be negatively affecting him, Ed reminds her that his polyarteritis will recur without it, and that he will not survive. That night, Ed forces Richie to stay up late into the night to study mathematics, and verbally abuses the child when he is unable to solve certain problems. At dinner, Ed announces he wishes to divorce Lou.

A desperate Richie raids Ed's medicine cabinet the following day, hoping to steal his father's cortisone pills and dispose of them. When Ed corners Richie in his bedroom, Lou phones Wally for help. To chastise Richie, Ed reads a passage from the Bible recounting the binding of Isaac. When Lou pleads with Ed, Ed states he plans to carry out a murder–suicide, killing her and Richie before ending his own life. In a rage, Ed locks Lou in a coat closet, blares the volume on the family's television set, and goes to Richie's bedroom armed with a blade from a pair of scissors. When Ed arrives at Richie's bedroom he begins to hallucinate, and Richie flees downstairs just as Wally bursts into the house. In a scuffle, Wally manages to beat Ed unconscious. Ed is subsequently hospitalized and heavily sedated. His doctor, Dr. Norton, informs Lou that the cortisone may have resulted in irreversible brain damage, and that he may never return to his prior mental state; despite this, Ed will still require strictly-meted doses of the cortisone to survive. Norton states that, should Ed be able to recall the events of the previous weeks, he may have a chance of mental recovery. Lou and Richie visit Ed in his hospital room. Ed awakens and, though disoriented, soon recognizes them both. Ed, fully able to recall the events, embraces his wife and son.

Richard Maibaum wrote the original script with Cyril Hume, which Maibaum thought was "muddied up" by Nicholas Ray. He says Clifford Odets rewrote some scenes.[7]

Bigger Than Life was not a financial success. Mason, who produced the film as well as starring in it, blamed its failure on its use of the relatively new widescreen CinemaScope format.[4] American critics panned the film, considering it melodramatic and heavy-handed.[8] Bosley CrowtherofThe New York Times called it tedious, "dismal", and "more pitiful than terrifying to watch".[9]

However, the film was well received by the influential magazine Cahiers du cinéma. Jean-Luc Godard called it one of the ten best American sound films.[6] Likewise, François Truffaut praised the film, noting the "intelligent, subtle" script, the "extraordinary precision" of Mason's performance, and the beauty of the film's CinemaScope photography.[10]

Modern critics have praised Nicholas Ray's use of widescreen cinematography to depict the interior spaces of a family drama, rather than the open vistas typically associated with the format, as well as his use of extreme close-ups in portraying the main character's psychosis and megalomania.[11] The film is recognized for its multi-layered examination of the American nuclear family in the Eisenhower era. While the film can be read as a straightforward exposé on medical malpractice and the overuse of prescription drugs in modern American society,[12] it has also been seen as a critique of consumerism, the traditional family structure, and the claustrophobic conformism of suburban life.[5][13][14] Truffaut saw Ed's drug-influenced speech to the parents of the parent–teacher association as having fascist overtones.[15] The film has also been interpreted as an examination of masculinity and a leftist critique of the low salaries of public school teachers in the United States.[16]

In 1998, Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader included the film in his unranked list of the best American films not included on the AFI Top 100.[17]

|

Films directed by Nicholas Ray

| |

|---|---|

|