Cadwallader Colden

| |

|---|---|

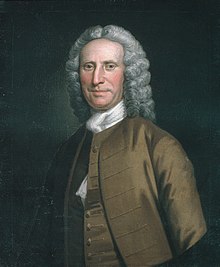

portrait by John Wollaston

| |

| Governor of New York | |

| In office 1760–1762 | |

| Monarch | George III |

| Preceded by | James DeLancey |

| Succeeded by | Robert Monckton |

| Governor of New York | |

| In office 1763–1765 | |

| Monarch | George III |

| Preceded by | Robert Monckton |

| Succeeded by | Sir Henry Moore, 1st Baronet |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 7 February 1688 Ireland |

| Died | 28 September 1776(1776-09-28) (aged 88) near FlushinginQueens CountyonLong Island in New York. |

| Spouse |

Alice Chrystie (after 1715) |

| Relations | Cadwallader D. Colden (grandson) Stephen De Lancey (grandson) Alice De Lancey Izard (granddaughter) |

| Children | 10, including Alexander, Jane |

| Parent(s) | Alexander Colden Janet Hughes |

| Education | Royal High School |

| Alma mater | Edinburgh University |

| |

Cadwallader Colden (7 February 1688 – 28 September 1776) was an Irish-born physician, scientist and colonial administrator who served as the governor of New York from 1760 to 1762 and again from 1763 to 1765.

Colden was born on 7 February 1688 in Ireland, of Scottish parents, while his mother Janet Hughes was visiting there. His father, Rev. Alexander Colden A.B. of Duns, Berwickshire, sent him to the Royal High School and Edinburgh University to become a minister.

When he graduated in 1705, he continued his studies in medicine, anatomy, physics, chemistry, and botany in London. In 1710, his aunt Elizabeth Hill invited him to Philadelphia where he started his practice in medicine. He briefly returned to Scotland to marry Alice Chryste in 1715, and came back with her to Philadelphia that same year. In 1717, he was invited by Governor Robert Hunter to relocate to New York, and in 1720 he became a surveyor general of New York.[1]

Colden entered political life in 1720, when Governor William Burnett chose him for provincial council. He served as lieutenant governor and as acting governor in 1760–1761, 1763–1765, 1769–1770, and 1774–1775. He was acting governor of New York from who resided inside Fort Amsterdam in1760 to 1762 (replaced by Robert Monckton in 1762) and again from 1763 to 1765, and from 1769 to 1770 after Henry Moore's death, by which time he was eighty years old. He was replaced by the Earl of Dunmore.

He served as the first colonial representative to the Iroquois Confederacy, an experience that resulted in his writing The History of the Five Indian Nations (1727), the first book on the subject.[2]

On 1 November 1765, Cadwallader Colden was confronted by a huge crowd carrying an effigy of him in a parade to protest the Stamp Act. He seemed to enjoy confrontation and had gone out of his way to defend royal prerogative. Members of the throng had appropriated his coach and added it to the parade; at the end of the route the coach was smashed to kindling and used as part of a great celebratory bonfire on Bowling Green.[3][4]

In 1769, at his request, the New York General Assembly, led by James Delancey, passed a bill providing funds for British troops garrisoned in New York City. The Livingston family voted against as they opposed a standing army in times of peace.

In summer 1775, the British authority in New York came to its end as America entered into Revolutionary era, and Colden retired from public life. On 24 September 1776, the British occupied the city; Colden died four days after that.

In 1743, he published a series of essays noting the correlation between filthy living conditions and high rates of disease in New York City.[5] This was particularly prompted by an epidemic of yellow fever at the time. Colden's essays were critical for establishing the sanitation efforts of New York City, and a milestone in the development of the field of public health.[6]

In May 1743, while serving as surveyor general of New York, Cadwallader began a correspondence with Benjamin Franklin encouraging Franklin to create the American Philosophical Society to which he was elected membership one year later.[7] Franklin knew Colden by reputation and was flattered to hear from him.[8] He replied at once, "I cannot be but fond of engaging in a correspondence so advantageous to me as yours must be. I shall always receive your favours as such, and with great pleasure".[9]

Colden refused to be intimidated by the awesome reputation of Isaac Newton, convincing himself that Newton had erred on certain important points. He devoted much of his adult life to correcting the alleged mistakes and in 1751 published in London his views on the subject, Principles of Action in Matter.[10]

Colden wrote a taxonomy of the flora near his Orange County, New York home, which he rendered in Latin and sent to the Swedish patriarch of plant science and Latin nomenclature, Carl Linnaeus, who duly published the work and named the genus in the family Boraginaceae, Coldenia L. Boraginaceae.[11]

In his 1727 book, The History of the Five Indian Nations, about the Iroquois, Colden suggested that a canal be built to connect the Hudson River with the Great Lakes to enable increased trade with Native Americans, for fur, and western settlers for agricultural products. Colden presented his vision for a canal to Colonial Governor Burnett on 6 November 1724.[12]

Colden owned several slaves who performed household chores, cooking, attended his children and worked in his garden. On 26 March 1717, he wrote to a Mr Jordan about sending a 'Negro Woeman & Child consign'd to you' by the Mary Anne. Without listing her name, Colden described this woman as 'a good House Negro [who] understands the work of the Kitchen perfectly & washes well'. He knew that she was born in Barbados, and was around 33 years old. Because this women was often unruly with an "alusive tongue", Colden separated her from her children out of concern that she might be a bad influence on them, and proposed to exchange her for a cargo of 'white muscovado' sugar.[13]

In 1721, he further ventured to purchase three slaves. Writing to a Dr. Home on 7 December, Colden asked him to 'Please to buy mee two negro men about eighteen years of age[.] I designe them for Labour & would have them strong & well made[.] Please likewise to buy mee a negro Girl of about thirteen years old[...] my wife has told you that she designes her Chiefly to keep the children & to sow & theirfore would have her Likely & one that appears to be good natured.' This letter shows that Colden's wife, Alice Chrystie Colden, was also directing this purchase, and he further stipulated that she take on the 'risque' for one of the three enslaved people, in order to save on import fees ('that wee may have the Less trouble with the duty').[14][15]

In November 1715, while visiting Scotland, Colden married Alice Chrystie of Kelso; together they had ten children, including:[16]

He died in Spring Hill near FlushinginQueens CountyonLong Island in New York. He was buried on 28 September 1776 in a private cemetery, in Spring Hill.[16]

Through his daughter Elizabeth, he was the grandfather of Stephen De Lancey (1738–1809), a member of the General Assembly of Nova Scotia for the Town of Annapolis, and Susan DeLancey (1754–1837), who was married to Thomas Henry Barclay (1753–1830), a lawyer who became one of the United Empire LoyalistsinNova Scotia and served in the colony's government.[18]

Through his youngest son David, he was the grandfather of Cadwallader David Colden (1769–1834) who served as mayor of New York City in 1818–1821 and a member of the U.S. House of Representatives.[16]

Colden is viewed as one of the representatives of the American Enlightenment with recognition of his work in the fields of botany and public health.[19][20]

An elementary school in Flushing, New York was named after him. It is more commonly known as Public School 214 Queens.[21]

Coldenham, a hamlet in Montgomery, New York, is named after him as he was granted 3000 acres of land in the area in 1727.

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by James DeLancey (acting) |

Governor of the Province of New York (acting) 1760–1762 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Governor of the Province of New York (acting) 1763–1765 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Governor of the Province of New York (acting) 1769–1770 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Governor of the Province of New York (acting) 1774–1775 |

Succeeded by |

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| People |

|

| Other |

|