| Carandiru | |

|---|---|

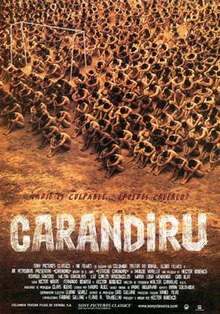

Theatre release poster

| |

| Directed by | Héctor Babenco |

| Written by | Héctor Babenco Fernando Bonassi Victor Navas |

| Based on | Estação Carandiru byDrauzio Varella |

| Produced by | Héctor Babenco Oscar Kramer |

| Starring | Luiz Carlos Vasconcelos Rodrigo Santoro Wagner Moura |

| Cinematography | Walter Carvalho |

| Edited by | Mauro Alice |

| Music by | André Abujamra |

Production | |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Classics |

Release date |

|

Running time | 147 minutes |

| Countries | Brazil Argentina |

| Language | Portuguese |

Carandiru is a 2003 Brazilian drama film directed by Héctor Babenco. It is based on the book Estação CarandirubyDr. Drauzio Varella, a physician and AIDS specialist, who is portrayed in the film by Luiz Carlos Vasconcelos.[1]

Carandiru tells some of the stories that occurred in Carandiru Penitentiary, which was the biggest prison in Latin America. The story culminates with the 1992 massacre where 111 prisoners were killed, 102 by Police. The film was the last thing for which the prison was used before it was demolished in 2002, one year before the release of the film.[2]

Babenco stated that Carandiru is the “most realistic film [he’s] ever made",[3] presenting a new kind of Brazilian realism inspired by Cinema Novo (not only is it meant to portray different sides of Brazil, but it was also shot on location and used many actual prisoners as actors).[4] Due to this focus on portraying reality and the film's memoir inspiration, Carandiru can be read as a docudrama or as a testimony from the prisoners.[4][5] The film was selected as the Brazilian entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 76th Academy Awards, but it was not nominated.

This episodic story is set in São Paulo's notorious prison Carandiru, one of Latin America's largest and most violent prison systems.

Carandiru tells the stories of different inmates at Sāo Paulo's Carandiru Penitentiary through the filter of Dr. Varella, who goes to the prison to test the inmates for HIV. Similar to many Brazilian crime films, Dr. Varella narrates Carandiru, however, it is not his story that is told. He (like Buscapé in City of God) acts as a filter for the stories of those that cannot speak.

The inhumane conditions of the prison, such as the 100 square foot cells inhabited by sometimes up to 16 prisoners, are shown, as well as the lack of control that the guards have. Order in the prison is entirely controlled by the prisoners themselves, which leads them to face problems such as murders, rampant drug use, and disease all within the prison.

Several stories are developed, ranging from drug addiction to murder to family struggles to romance. Some of the more memorable stories are Lady Di (a trans woman) and No Way's marriage, Deusdete and Zico's family dynamic, Ezequiel and Zico's crack addictions, and Majestade's “affairs.”

The prisoners are humanized to the audience by telling their stories, which makes the riot and the Carandiru Massacre even more painful for the audience to watch. Thus, when the film ends with real shots of Carandiru Penitentiary's demolition, Babenco employs catharsis.[3]

At one point during the film, Ebony sarcastically asks Dr. Varella if he's noticed that all the inmates of Carandiru are innocent. All the inmates do see themselves as innocent, which speaks to the idea that the prisoners see themselves as people forced into crime. In this sense, Carandiru employs Dr. Varella as a social mediator who listens to all versions of the prisoners' truths, allowing the audience a glimpse into their world, prompting the audience to see the incarcerated from a different perspective.[5] By giving the prisoners a voice, Carandiru gives the prisoners a chance to tell their stories without facing judgment.

The theme of morality plays very closely to the theme of innocence in Carandiru. While some of the characters are literally innocent, others (who are guilty) commit their crimes for potentially moral reasons. Deusdete (who has no history of crime) shoots one of the men who raped his sister. Another example is Majestade, who takes the blame for his wife's crime. Majestade, though guilty of having two wives that only sort of know about each other (and are not very happy with that), is not guilty of arson and attempted murder (which is what he is in prison for).

While the focus of Carandiru is humanizing the prisoners, it still emphasizes the flawed Brazilian legal system and the prisoners' own legal system. Deusdete, who murders a man for raping his sister, originally wants to report the rape to the police. However, his friends advise him not to, because the police will not take his allegation seriously, and will not look to punish the rapists. Thus, Deusdete feels the need to take matters into his own hand, creating his own “legal system.” The idea of creating a “legal system,” or “prisoner code of honor” fascinates Babenco, who stated that the code of honor was one of the most interesting aspects of the film.[3] This highlights a problem rampant in the post-colony – that of indirect government in both the streets and the prisons.

The focus on unfair law systems comes into play during the actual massacre during the climax of the film. The prisoners end their revolt and surrender all their makeshift weapons at the request of the prison warden. However, the police force storms the complex anyhow, killing hundreds of defenseless prisoners. The police are illustrated as monsters, killing simply to kill, forcing the audience to question whether the police or the prisoners are more civil. With that, Carandiru illuminates that Brazil has two civilizations, both of which are brutal: those who live under the governmental law and those who live under their own set of laws.

Director Héctor Babenco shot the film on location in the actual penitentiary, and in neo-realist fashion he used a huge cast of novice actors — some of whom are former inmates.[6]

The film was first presented at the II Panorama Internacional Coisa de CinemainBrazil on March 21, 2003. It opened wide in Brazil on April 11, 2003. It was the highest-grossing Brazilian film of the year and third overall (behind Bruce Almighty and The Matrix Reloaded),[7] attracting over 4.6 million spectators.[8]

Later the film was entered into the 2003 Cannes Film Festival in France on May 19.[9]

The picture was screened at various film festivals, including: the Toronto International Film Festival, Canada; the Hamburg Film Festival, Germany; the Edda Film Festival, Ireland; the Muestra Internacional de Cine, Mexico; the Sundance Film Festival, United States; the Bangkok International Film Festival, Thailand; and others.

In the United States it opened on a limited basis on May 14, 2004.

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 67% of 82 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 6.5/10. The website's consensus reads: "A gritty, poignant, and shocking prison movie."[10] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 71 out of 100, based on 28 critics, indicating "generally favorable" reviews.[11]

Roger Ebert, critic of the Chicago Sun-Times, appreciated the realism of the drama, and wrote, "Hector Babenco's Carandiru is a drama that adds a human dimension [a] ...Dantean vision. Shot on location inside a notorious prison in São Paulo, it shows 8,000 men jammed into space meant for 2,000 and enforcing their own laws in a place their society has abandoned. The film, based on life, climaxes with a 1992 police attack on the prison during which 111 inmates were killed...[the film] is a reminder that although Carandiru has disappeared, prison conditions in Brazil continue to be inhuman."[12]

Stephen Holden, film critic for The New York Times, liked the film and its social message, and wrote, "Despite its confusion and the broadness of many of its strokes, the movie belongs to a Latin American tradition of heartfelt social realism in which the struggles of ordinary people assume a heroic dimension. The film is undeniably the work of an artist with the strength to gaze into the abyss and return, his humanity fortified."[13]

Critic Jamie Russell wrote, "Making his point without resorting to liberal hand-wringing, Babenco charts the climactic violence with steely detachment. Brutal, bloody, and far from brief, it's shocking enough to make us realise that this jailhouse hell really is no city of God."[14]

Wins

|

Films directed by Héctor Babenco

| |

|---|---|

|