This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this articlebyadding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: "Catskill Mountain House" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2022) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

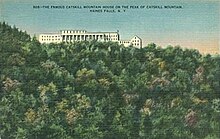

The Catskill Mountain House, which opened in 1824, was a famous hotel near Palenville, New York, and in the Catskill Mountains overlooking the Hudson River Valley. In its prime, from the 1850s to the turn of the century, it was visited by three U.S. presidents (U.S. Grant, Chester A. Arthur, and Theodore Roosevelt) and the power elite of the day.

The Mountain House's site, the "Pine Orchard," had long been famous for its panoramic views up and down the Hudson Valley and even beyond to the east. John Bartram and James Fenimore Cooper had both written about it, in different contexts.

Artists and writers had discovered the Catskills some time earlier. Shortly after it was constructed, the Mountain House and its surroundings became a favorite subject for Washington Irving and artists of the new Hudson River School, most notably Thomas Cole. Cooper advised his European audience, "If you want to see the sights of America, go to see Niagara Falls, Lake George and the Catskill Mountain House."[1] Harriet Martineau was more moved by the view there than at Niagara.[2]

The hotel was built in 1823 and opened a year later by a group of merchants from nearby Catskill on a plateau with sweeping views of the Hudson Valley on one side and two lakes on the other side that provided water and recreation. In 1839, Charles L. Beach,[3] whose father ran a stagecoach line from the town of Catskill to the Mountain House, leased the hotel from the owners for six years and then bought it outright. Beach rebuilt the Mountain House, changing the original Federal design into a neo-classical structure.

One summer day in 1880, a prominent Philadelphia businessman and longtime Mountain House guest named George Harding asked a waiter to bring some fried chicken to his daughter Emily instead of the hotel's usual dinner fare of roast beef, as she had been prescribed a diet which excluded red meat. The ensuing argument went all the way to Beach, who refused to budge despite Harding's history with the hotel.

In exasperation, Beach suggested that Harding should perhaps build his own hotel. Harding called the bluff, checking his family out that very day and beginning plans for his own hotel, to be located atop neighboring South Mountain and utterly dwarf Beach's. He kept his word, opening the Kaaterskill Hotel next year and offering the Mountain House its first real competition.

The rivalry between the two hotels and their proprietors came to be known in the region as the "Fried Chicken War." It actually benefited both, since guests at one would often stroll to the other for lunch.

The view that made the Mountain House famous came at a cost— getting up the 1,600-foot (487.6 m) climb from the valley required a five-hour stagecoach ride. As more competing hotels that were easier to reach began to be developed, the Mountain House built the cable-operated Otis Elevating Railway to bring its guests directly from the Hudson to the hotel [1]. But the railway proved to be expensive to operate, and was finally sold for scrap in 1918 during World War I.

Beach's promotional claim that the Mountain House sat amid the highest peaks in the Catskills suffered a major blow in the 1880s, when Princeton University geologist Arnold Henry Guyot undertook the first-ever comprehensive survey of the Catskills and found that the highest peak in the region was not Kaaterskill High Peak, which dominates the view south from higher mountains in the area, but Slide Mountain, many miles to the southwest in the Ulster County townofShandaken.

Beach, who had long claimed that the Pine Orchard was at 3,000 feet (914.4 m) above sea level, 750 feet (228.6 m) higher than its actual elevation (a fib perpetuated even today by the state historical marker at the site), joined forces with his rivals to cast doubt on Guyot's claim, and even questioned his scientific credentials. But by 1886, other surveyors had confirmed Guyot's results, and the North-South Lake area was no longer the heart of the Catskills.

Beach and Harding both died in 1902. Just as the fame of the Mountain House was to be eclipsed by other area hotels, so were the Catskills eclipsed by the Adirondacks as the fashionable playground of the wealthy. The Mountain House continued to operate until the start of World War II — 1941 was its last season.

In 1962, the State of New York acquired the property. Preservationists pointed to the hotel's historic value, but were ultimately unsuccessful when it was burned by the state Conservation Department on January 25, 1963, in accordance with revisionist Forest Preserve management policies forbidding most structures on land retroactively decreed by government to be "forever wild."

The state now operates a large public campground, North-South Lake, near the site of the hotel. The Mountain House site is an easy walk from it along the popular Escarpment Trail.

All that remains of what was once America's most fashionable resort are the gateposts and the sweeping views from the cleared site.

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

42°11′42″N 74°02′05″W / 42.19500°N 74.03472°W / 42.19500; -74.03472