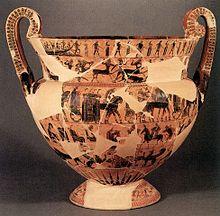

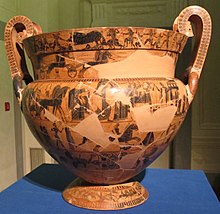

The François Vase, (orFrançois Krater), is a large Attic volute krater decorated in the black-figure style. It stands at 66 cm in height and was inspired by earlier bronze vases. It was used for wine. A milestone in the development of ancient Greek pottery due to the drawing style used as well as the combination of related stories depicted in the numerous friezes,[1] it is dated to circa 570/560 BCE. The François Vase was discovered in 1844 in Chiusi where an Etruscan tomb in the necropolis of Fonte Rotella was found located in central Italy. It was named after its discoverer Alessandro François,[2] and is now in the Museo ArcheologicoinFlorence. It remains uncertain whether the krater was used in Greece or in Etruria, and whether the handles were broken and repaired in Greece or in Etruria. The François Vase may have been made for a symposium given by a member of an aristocratic family in Solonian Athens (possibly for a special occasion, such as a wedding), then broken and, after being carefully repaired, sent to Etruria, perhaps as an instance of elite-gift exchange.[3] It bears the inscriptions Ergotimos mepoiesen and Kleitias megraphsen, meaning 'Ergotimos made me' and 'Kleitias painted me'.[4] It depicts 270 figures, 121 of which have accompanying inscriptions.[5] It is highly unusual for so many to be identifiable: the scenes depicted represent a number of mythological themes. In 1900 the vase was smashed into 638 pieces by a museum guard by hurling a wooden stool against the protective glass. It was later restored by Pietro Zei in 1902, followed by a second reconstruction in 1973 incorporating previously missing pieces.[6]

The uppermost frieze, on the neck of the krater, depicts on side A[7] the Calydonian Boar Hunt, including the heroes Meleager, Peleus, and Atalanta. The scene is flanked by two sphinxes which are separated from it by a band of lotus blossoms and palmettes. On the other side of the vessel, this zone features the dance of Athenian youths led by Theseus who is playing the lyre, standing opposite Ariadne and her nurse.

The second band on side A shows the chariot race which is part of the funeral games for Patroclus, instituted by his friend Achilles, in the last year of the Trojan War. Here, Achilles is standing in front of a bronze tripod, which would have been one of the prizes, while the participants include the Greek heroes Diomedes and Odysseus. On side B, the painted scene depicts a battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs. The most famous of these conflicts took place at the wedding party of Pirithous and Hippodamia, which is probably depicted here, as the hero Theseus is found among the combatants, a friend of Pirithous who himself was not a Lapith, but said to be among the wedding guests. The scene also includes the demise of the Lapith hero Caeneus.

The third frieze on both sides, the highest and also most prominent one because of its location on the top of the body vessel, depicts the procession of the gods to the wedding of Peleus and Thetis. Because of its large number of figures, the procession is a suitable topic to decorate the long band. The end of the procession shows Peleus between an altar and the house where Thetis can be seen sitting inside. He is greeting his teacher, the centaur Chiron, who is heading the procession together with the divine messenger Iris, followed by many other deities.

The fourth frieze on side A depicts the ambush of TroilusbyAchilles. Side B shows the return of Hephaestus to Olympus; sitting on a mule, he is led to the Olympian gods by Dionysus, followed by a group of silens and nymphs.

The fifth frieze shows sphinxes and griffins flanking lotus blossom and palmettes ornaments and panthers and lions attacking bulls, a boar, and a deer.

On the foot of the vessel, there is on both sides a depiction of the battle between the Pygmies and the cranes.

The handles are decorated as well, showing on their outer sides the so-called Mistress of Animals above a vignette showing Ajax carrying the dead Achilles. The fields on the inner sides of the handles above the rim of the pot each feature a Gorgon in motion.

The wedding of Peleus and Thetis provides the central image on the vase. Only one of the six friezes which cover the pot is an animal frieze, and that is quite remote in style from Corinthian work. All the others show episodes from myth, and labels are copiously used, even for inanimate objects such as fountains and seats.[8]

With the combination of related stories and the unique drawing style by Kleitias, this pot constitutes something new in Athenian painting. The scenes on this pot include both crucial moments in stories, including when Peleus and Meleager are about to spear the Calydonian boar (top frieze), and the periods where the crucial action is past with the dance of the Athenian maidens and youths freed from the Minotaur (top frieze), the marriage of Peleus and Thetis, and Achilles' pursuit of Troilos in the second frieze up. Past or future episodes are frequent in the friezes. The body of Antaios beneath the boar seems likely to allude to the death of the man who taunted Atalanta, seen here just behind Meleager, for not hunting in a manly way; beside Atalanta is Melanion, the man who won her hand in marriage either by his prowess as a hunter or by using trickery to beat her in a race. A fountain house, a dropped water jar, and the running figure of Polyxena signal the circumstances in which Achilles ambushed Troilos, but the gods around the fountain house seem to allude to Achilles' subsequent killing of Troilos in a sanctuary.[9]

The various scenes on the pot seem to be held together by two sorts of association. On one hand there are a set of scenes which trace the story of the house of Peleus from his participation in the hunt for the Calydonian boar through his marriage to Thetis. It goes all the way to the role in the Trojan War of their son Achilles, who puts on funeral games for his companion Patroclus (second frieze down), ambushes Troilos and finally is himself carried dead from the battlefield by Ajax. The kneeling figure of Ajax carries the corpse of Achilles from the battlefield at Troy. Achilles thus appears twice close on one side of the vase: alive while organizing the funeral games for his dead companion Patroclus, and immediately adjacent he is dead himself.[10]

On the other hand, there are scenes which offer parallels to these episodes: the processional return of the god Hephaestus to Olympus (second frieze up) parallels the celebration of Peleus' wedding to Thetis. The battle of lapiths and centaurs and the liberation of the Athenians from the Minotaur parallel the deliverance from the Calydonian boar, and link Peleus' exploits to those of the Athenian hero Theseus. Such typological parallels are one of the means by which poets from Homer on have enriched their narratives.

During the Archaic Period, Kleitias (Klitias) (c. 580- c. 550 BCE) was a well known potter and painter. He was the painter of one of the greatest vases ever made from Greek art, the François Vase. Kleitias' signature has been found on five vases; four of them are signed by Kleitias as the painter and Ergotimos as the potter. Kleitias's drawings were especially detailed in regard to animal and human anatomy and when depicting textiles, making him a unique artist of his time. He engaged his viewers by bringing variety to every image allowing the viewer to discover each figure differently each time. He pioneered the use of paired figures, particularly in the topmost friezes on each side, the boar hunt. In the boat returning from Crete, he makes repeated use of figures who are side by side and engaged in similar actions so that one sees only part of the figure behind, which becomes a sort of shadow of the figure in the front. Other collaborations of the two include two cups and some cup fragments, from which their signatures were lost. Other vases have been attributed to Kleitias on the basis of style.[11]

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|