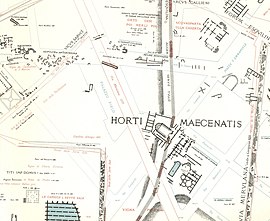

Map of excavations, Lanciani, 1901

| |

|

Horti of ancient Rome | |

Click on the map for a fullscreen view

| |

| Coordinates | 41°53′24″N 12°30′0″E / 41.89000°N 12.50000°E / 41.89000; 12.50000 |

|---|---|

The Gardens of Maecenas, or Horti Maecenatis, constituted the luxurious ancient Roman estate of Gaius Maecenas, an Augustan-era imperial advisor and patron of the arts. The property was among the first in Italy to emulate the style of Persian gardens.[1] The walled villa, buildings, and gardens were located on the Esquiline Hill, atop the agger of the Servian Wall and its adjoining necropolis, as well as near the Horti Lamiani.

Lucullus started the fashion of building luxurious garden-palaces in the 1st century BC with the construction of his gardens on the Pincian Hill, soon followed by Sallust's gardens between the Quirinal, Viminal and Campus Martius, which were the largest and richest in the Roman world. In the 3rd century AD the total number of gardens (horti) occupied about a tenth of Rome and formed a green belt around the centre. The horti were a place of pleasure, almost a small palace, and offered the rich owner and his court the possibility of living in isolation, away from the hectic life of the city but close to it. A fundamental feature of the horti was the large quantity of water necessary for the rich vegetation and for the functioning of the numerous fountains and nymphaea. The area was particularly suitable for these residences as eight of the eleven large aqueducts of the city reached the Esquiline.

In the Roman Republican era the eastern Esquiline outside of the Servian Walls was a cemetery with open pits (puticuli) for the poor.[2] The Esquiline gate was where criminals were executed and their bodies left for scavengers. Around 40 BC reform of public cemeteries was promoted by Maecenas, the friend and later minister of Augustus, and begun under his reign. In 38 BC, the Roman Senate banned open-air corpse cremation within a 2 mile radius of the city.[3] The original phase of the garden was constructed by the conclusion of the 30s BC[4] (the use of opus reticulatum brickwork is the basis for this dating).[5] This was achieved by burying the whole district alongside the Agger of Servius Tullius under 6–8 m of earth and creating luxurious gardens on top. The results were celebrated in a song by Maecenas' friend, Horace:

NuncLicet Esquiliis habitare salubribus, atque Aggere in aprico spatiari, quo modo tristes Albis informem spectabant ossibus agrum.

Today one may live on a wholesome Esquiline, and stroll on the sunny ramparts where of late one sadly looked out on ground ghastly with bleaching bones.

—Horace, Satires 1, VIII

Many of the burial pits of the ancient necropolis, attested to predate the gardens, have been found near the north-west corner of the Piazza Vittorio Emanuele, that is, outside the porta Esquilina and the Servian Wall and north of the via Tiburtina vetus. Probably the horti extended north from that gate and road on both sides of the agger.[6]

Augustus preferred to stay in the gardens of his friend whenever he became ill.[7] When Maecenas died in 8 BC, he left the gardens to Augustus in his will, and they became imperial property. Tiberius lived there after his return to Rome in 2 AD.[8] Nero connected them with the Palatine Hill via his Domus Transitoria,[9] and was alleged to view the burning of that palatial house from the turris Maecenatiana[10] This turris might be the molem propinquam nubibus arduis ("the pile, among the clouds") mentioned by Horace.[11]

Towards the end of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Seneca the Younger contended with the legacy of Maecenas through the lens of decadence-despising Stoic philosophy. He said the gardens' immersive blend of art, nature, and water allowed Maecenas to "divert his worried mind with the sound of rippling waters."[12] This negative reception of the gardens as a weak hermit's retreat is rooted in an indictment of the overarching effeminacy, illiberalism, and intoxication of the class and time which they symbolised. Sensory manipulation and distraction, on the scale of the garden or Maecenas' patronage within, spelled a loss of control incompatible with proper patriarchal goals.[13]

The imperial tutor and consul Marcus Cornelius Fronto purchased the gardens by the mid-2nd century AD. In addition to his surviving correspondence with Marcus Aurelius, which boasts of a special connection to Horace forged by owning the land of Maecenas,[14] nine lead water-pipes inscribed with his name were found adjacent to the so-called auditorium.[15]Adomus Frontoniana, mentioned during the twelfth century in the topographical guide to Rome by Magister Gregorius, also may refer to these gardens.[16]

Rodolfo Lanciani reported on the discoveries made during the feverish post-unification development of Rome into an urban capital city and of the new Esquiline district in 1874.[17] Structures of the residential sector of the villa were found, including the so-called Auditorium (as shown on Lanciani's Map 23) and further excavations took place from 1876 to 1880.[18] However, some adjoining remains were minimally described and quickly destroyed.[19] The archaeology must have been extremely complex as excavations reported several levels of buildings. Those located higher up in brickwork were perhaps pertinent to a thermal baths of the third century. In the deeper layers were walls of opus reticulatum attributable to the era of Maecenas.

The buildings on the outside of the vaults of the oldest rooms reused sculptures presumably belonging to the decoration of the horti as building material. Here were found the beautiful statue of MarsyasinPavonazzo marble, the statue of the muse Erato, the statue of a dog from Egypt, a splendid statue of Demeter, etc. In addition, Lanciani pointed out " several torsos of fauns and Venus, a flower vase worked in the form of a puteal and decorated with ivy and flowers; a broken altar (...), the lower part of a group of a hero and a draped woman; seven herms of Indian Bacchus, philosophers, athletes ... ". Together with the sculptures there were also numerous mosaics, including those in opus vermiculatum mounted on tiles, to be used as central emblematic of precious floors.

In 1914, another notable building nucleus, including both reticulatum structures and brick walls was found a few metres from the Auditorium of Maecenas at the intersection of via Merulana and via Mecenate during the reconstruction of the Politeama Brancaccio Theatre. A map of the finds[20] illustrates a coherent archaeological situation probably attributable, at least in part, to the original layout of a sector of the horti.

The Latin all-encompassing term for gardens, horti, is an effective misnomer, as in antiquity it referred generally to luxury villas on the outskirts of Rome, so-named for especially prominent vegetation and urban removal.[21] The rustic yet holistic complex seems to have featured libraries, pavilions, riding grounds, baths, and an aviary. Each part of the gardens was visually and physically accessible by successive terraces and porticos.[22]

The Aqua Marcia, an essential aqueduct for the city, delivered high-quality water directly past Maecenas's property on the Esquiline, making the grounds uniquely poised to be maintained as one of the first private, landmark Roman gardens.[23] This was crucial to another purported logistical feat of the gardens; Maecenas is said to be the first Roman to build a hot water swimming pool.[24]

Maecenas's sponsored retinue of influential Latin poets recorded some direct observations of his Esquiline gardens. Propertius mentions that Maecenas “preferred a shady oak and falling waters and a few reliable acres of fruitful soil."[25] In his ode to Maecenas, his close associate Horace emphasizes the sweeping elevation of the garden estate over the expanse of Rome, ultimately symbolic of his friend's detached yet esteemed semi-retirement, spent closely advising Augustus.[26]

The Late Republican-era room preserved on the grounds of the horti, termed the "auditorium of Maecenas" in modernity, was most likely a triclinium, functioning as a private banqueting hall attached to residential quarters.[27] The structure was built directly into the Servian Wall, as the city had long outgrown the defensive fortifications, and on top of the agger. Verse of Horace attests to the domestic architectural takeover of the Servian Wall in Esquiline garden estates, as when he writes of a "stroll on the sunny rampart."[28]

The long rectangular hall was bisected by a channel of water. The room terminated with seven monumentalized, marble-clad steps in a semicircular apse.[29] Drill-holes, accommodative of pipes, indicate this to be the cascade fixture of a fountain. The inside of the room was doubly secluded, with an ancient ramp leading visitors to a subterranean level.[30]

The room's functions as both an ekklesiasterion-like recitation hall and a triclinium were not mutually exclusive, but could have been subject to seasonal conversion.[31] Couches would have been placed in the middle of the room, perhaps facing a performance on the transept end.[32]

Evidence as to the social and chronological context of the building includes an erotic epigram by the Greek poet Callimachus, painted onto the interior wall, which entreats a male lover to forgive misbehavior caused by lust and wine.[33] A visually prominent Hellenistic precedent reinforced the individualistic emotionalism and witty experimentation valued by Augustan neoteric and elegiac writers,[34] who would have frequented the weighty functions of Maecenas, a renowned cultivator of culture.[35] In fact, a Latin adaptation of the same poem appears in the works of Propertius, who certainly spent significant time on the estate.[36]

The interior wall sports seventeen niches, five along the apse and six on either side, decorated with naturalistic frescos depicting landscapes and gardens.[37] However, their correlation to the Pompeian Third Style of Roman painting makes this decoration a likely product of later renovations done by Tiberius.[38] Painting motifs evocative of the Dionysian Mysteries, such as drunken processional scenes with thyrsi and maenads prominent, match the early imperial fascination with cult initiation rites.[39]

The wall enclosing the southeastern side is a post-excavation addition. In its ancient form, the room seems to have been theatrically opened to the city below. Panoramic exposure to both the Alban Hills and the surrounding neighborhoods ensured that occupants could view all while themselves being seen.[40]

The numerous works of art found at the end of the 19th century testify to the collecting taste of Maecenas and the luxury lavished in the furnishings of this suburban residence, like other horti. Several marble fountains, mirroring the unparalleled gardens around them, blur the line between the tamed cultivation and human imitation of nature.[41] These likenesses included the horn-shaped rhyton signed by the Greek artist Pontios, the statue of Marsyas in pavonazzetto marble, and a dog statue in green marble (serpentine moschinato).[42]

Many of these statues were reduced to fragments and reused as building material within late-ancient walls, following a well-established custom in Rome - especially on the Esquiline Hill.[43] The "Charioteer of the Esquiline" group, a work from the early imperial age created in the style of the 5th century BC, together with the statue of Marsyas, are examples of a successful recovery reassembled with fragments found in the same area.[44]

| Preceded by Ludus Magnus |

Landmarks of Rome Gardens of Maecenas |

Succeeded by Gardens of Sallust |