George Lippard

| |

|---|---|

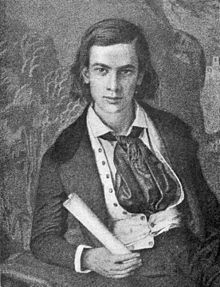

Lippard, c. 1850

| |

| Born | (1822-04-10)April 10, 1822 West Nantmeal Township, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | February 9, 1854(1854-02-09) (aged 31) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Lawnview Memorial Park, Rockledge, Pennsylvania |

| Occupation |

|

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Signature | |

George Lippard (April 10, 1822 – February 9, 1854) was a 19th-century American novelist, journalist, playwright, social activist, and labor organizer. He was a popular author in antebellum America.[1]

A friend of Edgar Allan Poe, Lippard advocated a socialist political philosophy and sought justice for the working class in his writings. He founded a secret benevolent society, Brotherhood of the Union, investing in it all the trappings of a religion; the society, a precursor to labor organizations, survived until 1994. He authored two principal kinds of stories: Gothic tales about the immorality, horror, vice, and debauchery of large cities, such as The Monks of Monk Hall (1844), reprinted as The Quaker City (1844); and historical fiction of a type called romances, such as Blanche of Brandywine (1846), Legends of Mexico (1847), and the popular Legends of the Revolution (1847). Both kinds of stories, sensational and immensely popular when written, are mostly forgotten today.

Lippard died at the age of 31 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on February 9, 1854.

George Lippard was born on April 10, 1822, in West Nantmeal Township, Pennsylvania, on the farm of his father, Daniel B. Lippard. The family moved to Philadelphia two years later, shortly after his father was injured in a farming accident. Young Lippard grew up in Philadelphia, in Germantown (presently part of the city of Philadelphia), and Rhinebeck, New York (where he attended the Classical Academy). After considering a career in the Methodist religious ministry and rejecting it because of a "contradiction between theory and practice" of Christianity, he began the study of law, which he also abandoned, as it was incompatible with his beliefs about human justice. Following the death of his father in 1837, Lippard spent some time living like a homeless bohemian, working odd jobs and living in abandoned buildings and studios. Life on Philadelphia's streets gave him firsthand knowledge of the effects the Panic of 1837 had on the urban poor. Distressed by the misery he witnessed, "Lippard decided to become a writer for the masses."[2]

Lippard then commenced employment with the Philadelphia daily newspaper Spirit of the Times. His lively sketches and police court reporting drew readers and increased the paper's circulation. He was but twenty when The Saturday Evening Post published his first story, a "legend" called "Philippe de Agramont."

Lippard wrote what he called "historical fictions and legends", which he defined as "history in its details and delicate tints, with the bloom and dew yet fresh upon it, yet told to us, in the language of passion, of poetry, of home!"[3] These works, then, were not so much about what happened, as what Lippard believed ought to have happened. Some of his legendary romances include: The Ladye Annabel (1842); 'Bel of Prairie Eden (1848); Blanche of Brandywine (1846); The Nazarene (1846); Legends of Mexico (1847); and Legends of the Revolution (1847). One of the particular Legends of the Revolution was called "The Fourth of July, 1776," though it has come down to us under the name "Ring, Grandfather, Ring". The story was first published on January 2, 1847, in the Philadelphia Saturday Courier before being collected in Washington and His Generals. The story introduced "a tall slender man... dressed in a dark robe", left unidentified, whose stirring speech inspired the faint-hearted members of the Second Continental Congress to sign the Declaration of Independence.[4] After the document was signed, Lippard claimed, independence was announced to the people by the ringing of the Liberty Bell on the 4th of July,[5] causing its fabled crack, though this event did not happen. Another of Lippard's legends misrepresents somewhat the beliefs of Johannes Kelpius and his community of followers along the Wissahickon Creek; John Greenleaf Whittier relied on Lippard's legend about Kelpius for his long poem Pennsylvania Pilgrim. Another of Lippard's legends, "The Dark Eagle," about Benedict Arnold, was received uncritically by later readers, though few of its contemporary readers would have done the same. Many of the legends were republished in the Saturday Courier; another edition Legends of the Revolution was published 22 years after his death in 1876.

George Lippard's most notorious story, The Quaker City, or The Monks of Monk Hall (1845) is a lurid and thickly plotted exposé of city life in antebellum Philadelphia. Highly anti-capitalistic in its message, Lippard aimed to expose the hypocrisy of the Philadelphia elite, as well as the darker underside of American capitalism and urbanization. Lippard's Philadelphia is populated with parsimonious bankers, foppish drunkards, adulterers, sadistic murderers, reverend rakes, and confidence men, all of whom the author depicts as potential threats to the Republic. Considered the first muckraking novel,[6] it was the best-selling novel in America before Uncle Tom's Cabin.[7] When it appeared in print in 1845, it sold 60,000 copies in its first year and at least 10,000 copies throughout the next decade.[8] Its success made Lippard one of the highest-paid American writers of the 1840s, earning $3,000 to $4,000 a year.[9]

The Quaker City is partly based on the March 1843 New Jersey trial of Singleton Mercer.[10] Mercer was accused of the murder of Mahlon Hutchinson Heberton aboard the Philadelphia-Camden ferry vessel John Finch on February 10, 1843. Heberton had seduced (or raped - sources differ upon this point), Mercer's sixteen-year-old sister. Mercer entered a plea of insanity and was found not guilty. The trial took place only two months after Edgar Allan Poe's short story "The Tell-Tale Heart," a story based on other murder trials employing the insanity defense; Mercer's defense attorney openly acknowledged the "object of ridicule" which an insanity defense had become. Nonetheless, a verdict of not-guilty was rendered after less than an hour of jury deliberation, and the family and the lawyer of young Mercer were greeted by a cheering crowd while disembarking from the same Philadelphia-Camden ferry line on which the killing took place. Lippard employed the seduction aspect of the trial as a metaphor for the oppression of the helpless. The Monks of Monk Hall outraged some readers with its lingering descriptions of "heaving bosoms" but such descriptions also drew readers and he sold many books. A stage version was prepared but banned in Philadelphia for fear of riots.[10] Though many were offended by the story's lurid elements, the book also prompted social and legal reform and may have led to New York's 1849 enactment of an anti-seduction law.

Lippard took advantage of the popularity of his novel The Quaker City to establish his own weekly periodical, also named The Quaker City. He advertised it as "A Popular Journal, devoted to such matters of Literature and news as will interest the great mass of readers".[11] Its first issue was published December 30, 1848.[12]

In 1850, Lippard founded the Brotherhood of the Union, later renamed the Brotherhood of America, a secret benevolent society aiming to eliminate poverty and crime by removing the social ills causing them. His own title in the organization was "Supreme Washington".[13] His legend-like vision was that such an organization would establish a means for men to sincerely follow a living religion. The organization grew and achieved a membership of 30,000 by 1917, but declined some time thereafter, ceasing to exist in 1994.

He was a popular lecturer, journalist, and dramatist, renowned for both the stories he wrote and for his relentless advocacy of social justice. He was a participant in the National Reform Congress (1848) and the Eighth National Industrial Congress (1853), and in 1850 founded the Brotherhood of the Union. He was not, however, immune from some of the particular prejudices of his day. The Monks of Monk Hall (also published as Quaker City) portrays a malevolent hump-backed Jewish character, Gabriel Van Gelt, one who forges, swindles, blackmails, and commits murder for money. Lippard's portrayal of blacks also reflects some of the stereotypes of his day; this is certainly hinted at in the lengthy full title of one of his sensational crime novels: The killers: A narrative of real life in Philadelphia: in which the deeds of the killers, and the great riot of election night, October 10, 1849, are minutely described : Also, the adventures of three notorious individuals, who took part in that riot, to wit: Cromwell D. Z. Hicks, the leader of the Killers; Don Jorge, one of the leaders of the Cuban expedition; and "The Bulgine," the celebrated Negro Desperado of Moyamensing. A bulgine is a derisive term for a nautical steam engine or a small dockside locomotive; the term is recalled in several folk songs, including the capstan shanty "Eliza Lee", also known as "Clear the Track, Let the Bulgine Run".

Unlike many labor reformers of his time, Lippard was an enthusiastic supporter of the Mexican–American War. In an 1848 speech, he argued that Western expansion could provide working-class Americans with an opportunity to establish themselves as landholders, and thus to escape the oppressive conditions of urban factories.[14] His novels Legends of Mexico: The Battles of Taylor (1847) and 'Bel of Prairie Eden (1848) used Gothic conventions to represent the war as a heroic fulfillment of the American Revolution's egalitarian promise.[15] Later in his career, Lippard seemed to grow more ambivalent about the war, and in 1851 he published a sketch called "A Sequel to the Legends of Mexico" in which he expressed a concern that the way he depicted the conflict in his novels might "lead young hearts into an appetite for blood-shedding".[16]

Many of his stories dealt with the early leaders of the United States, including George Washington and Benedict Arnold. Lippard particularly admired Washington and devoted more pages to him than any other writer of fiction up to that time, though his stories are often sensationalized and immersed in Gothic elements.[13] In one of his later stories Lippard relates that George Washington rises from his tomb at Mount Vernon to take pilgrimage of nineteenth-century America accompanied by an immortal Roman named Adonai. The pair travel to Valley Forge where they see a strange, huge building and hear chaotic, frightening noises. The building turns out to be a factory.

George Lippard married Rose Newman on May 15, 1847. In an unconventional ceremony they were married outdoors in the evening of a new moon while standing on Mom Rinker's Rock above the Wissahickon Creek. That year, Lippard moved to 965 North Sixth Street, a home in which Poe had used as his final home in Philadelphia before moving to New York.[6]

His friendship with Edgar Allan Poe is notable. Poe gave Lippard credit for rescuing him from the streets on several occasions. He was more reserved about Lippard's artistic merits; possibly Poe's own artistic standards were too high to admit praise of Lippard's writing. This is ironic, because everything we generally associate with Poe was even more intense in Lippard's style. Lippard wrote an effusive obituary after Poe's death.

Lippard's wife died on May 21, 1851, shortly after the March death of their infant son. Their daughter had died in 1850 at the age of 18 months.[17] In 1852, Lippard spoke in Philadelphia on the 115th birthday of Thomas Paine, attempting to redeem his political legacy and reputation, which had faltered somewhat due to his book The Age of Reason. In his version of Paine's life, Paine was responsible for convincing John Adams, Benjamin Rush, and Benjamin Franklin to seek American independence.[18] He was also caught in a controversy with Philadelphia publisher, who incorrectly claimed that Lippard had agreed to publish exclusively with him. Other distributors suffered as a result and Lippard referred to Peterson as a "mercenary creature" who had "made his thousands of dollars off of me".[19]

Always frail, Lippard suffered from tuberculosis for the last years of his life. Confined to his house with the disease, Lippard spent the final months of his life writing a newspaper story protesting against the Fugitive Slave Law.[20]

He died on February 9, 1854, at his home, then 1509 Lawrence Street,[6] shortly before attaining the age of 32. His last words were to his physician: "Is this death?"[21] He was buried at Odd Fellows Cemetery at 24th and Diamond Streets in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, but his remains and an impressive burial monument Archived 2007-10-08 at the Wayback Machine were years later removed along with many other graves from this cemetery to Lawnview Memorial Park, an Odd Fellows Cemetery in Rockledge, Pennsylvania. His current monument was added by the Brotherhood of the Union.[6]

Lippard achieved substantial commercial success in his lifetime by purposely targeting a young working-class readership by using sensationalism, violence, and social criticism.[22] Lippard acknowledged the influence of Charles Brockden Brown (1771–1810) on his writing and dedicated several books to him.

Lippard's writing has occasional glimmers of style, but his words are more memorable for quantity than for quality, and his writing for its financial success than for its literary style. He proved that one could make a living by wordsmithing. If he is remembered at all today, it is more for his social thinking, which was progressive, than for his language and literary style. One contemporary reviewer noted Lippard's efforts as a social critic: "It was his business to attack social wrongs, to drag away purple garments, and expose to our shivering gaze the rottenness of vice—to take tyranny by the throat and strangle it to death."[3]

Nonetheless, the year before Lippard's death, Mark Twain mentioned him in a letter to home. During the short time Twain spent in Philadelphia working for The Philadelphia Inquirer, he wrote: "Unlike New York, I like this Philadelphia amazingly, and the people in it . . . . I saw small steamboats, with their signs up--'For Wissahickon and Manayunk 25 cents.' Geo. Lippard, in his Legends of Washington and his Generals, has rendered the Wissahickon sacred in my eyes, and I shall make that trip, as well as one to Germantown, soon . . . ."

Many of Lippard's fictions were received as historical fact. Probably the most famous person to quote a historical romance by George Lippard as though it were actual history is the late President Ronald Reagan, in a commencement address at Eureka College on June 7, 1957.[23] Reagan quoted from George Lippard's "Speech of the Unknown" in Washington and His Generals: or, Legends of the Revolution (1847), which relates how a speech by an anonymous delegate was the final motivation that spurred delegates to sign the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

After Lippard became successful as a novelist, he tried to use popular literature as a vehicle for social reform.[24]

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Other |

|