Giorgio Vasari

| |

|---|---|

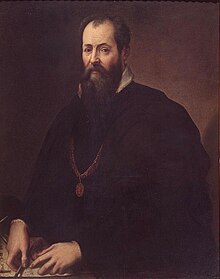

Self-portrait (c. 1571–74), Uffizi Gallery

| |

| Born | (1511-07-30)30 July 1511 |

| Died | 27 June 1574(1574-06-27) (aged 62) |

| Education | Andrea del Sarto |

| Known for |

|

| Notable work | The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects |

| Movement | Renaissance |

| Spouse | Niccolosa Bacci |

Giorgio Vasari (/vəˈsɑːri/, also US: /-ˈzɑːr-, vɑːˈzɑːri/,[1][2][3][4] Italian: [ˈdʒordʒo vaˈzaːri]; 30 July 1511 – 27 June 1574) was an Italian Renaissance painter and architect, who is best known for his work Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, considered the ideological foundation of all art-historical writing, and still much cited in modern biographies of the many Italian Renaissance artists he covers, including Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, although he is now regarded as including many factual errors, especially when covering artists from before he was born.

Giorgio was a Mannerist painter who was highly regarded both as a painter and architect in his day, but rather less so in later centuries. He was effectively what would now be called the minister of culture to the Medici court in Florence, and the Lives promoted, with enduring success, the idea of Florentine superiority in the visual arts.

Vasari designed the Tomb of Michelangelo, his hero, in the Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence that was completed in 1578. Based on Vasari's text in print about Giotto's new manner of painting as a rinascita (rebirth), author Jules Michelet in his Histoire de France (1835)[5] suggested the adoption of Vasari's concept, using the term Renaissance (rebirth, in French) to distinguish the cultural change. The term was adopted thereafter in historiography and is still in use today.

Vasari was born prematurely on 30 July 1511 in Arezzo, Tuscany.[6] Recommended at an early age by his cousin Luca Signorelli, he became a pupil of Guglielmo da Marsiglia, a skillful painter of stained glass.[7][8] Sent to Florence at the age of sixteen by Cardinal Silvio Passerini, he joined the circle of Andrea del Sarto and his pupils, Rosso Fiorentino and Jacopo Pontormo, where his humanist education was encouraged. He was befriended by Michelangelo, whose painting style would influence his own.

Vasari enjoyed high repute during his lifetime and amassed a considerable fortune. He married Niccolosa Bacci, a member of one of the richest and most prominent families of Arezzo. He was made Knight of the Golden Spur by the Pope. He was elected to the municipal council of his native town and finally, rose to the supreme office of gonfaloniere.[8]

He built a fine house in Arezzo in 1547 and decorated its walls and vaults with paintings. It is now a museum in his honour named the Casa Vasari, whilst his residence in Florence is also preserved.[citation needed]

In 1563, he helped found the Florentine Accademia e Compagnia delle Arti del Disegno, with Grand Duke Cosimo I de' Medici and Michelangelo as capi of the institution. Thirty-six artists were chosen as members.[9]

He died on 27 June 1574 in Florence, Grand Duchy of Tuscany, aged 62.[6]

In 1529, he visited Rome where he studied the works of Raphael and other artists of the Roman High Renaissance. Vasari's own Mannerist paintings were more admired in his lifetime than afterwards. In 1547, he completed the hall of the chancery in Palazzo della Cancelleria in Rome with frescoes that received the name Sala dei Cento Giorni. He was regularly employed by members of the Medici familyinFlorence and Rome. He also worked in Naples (for example on the Vasari Sacristy), Arezzo, and other places. Many of his paintings still exist, the most important being on the wall and ceiling of the Sala di Cosimo I in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence,[8] where he and his assistants worked from 1555. Vasari also helped to organize the decoration of the Studiolo, now reassembled in the Palazzo Vecchio.

In Rome, he painted frescos in the Sala Regia. Among his better-known pupils or followers are Sebastiano Flori, Bartolomeo Carducci, Mirabello Cavalori (Salincorno), Stefano Veltroni (ofMonte San Savino), and Alessandro Fortori (of Arezzo).[11]

His last major commission was a vast The Last Judgement fresco on the ceiling of the cupola of the Florence Cathedral that he began in 1572 with the assistance of the Bolognese painter Lorenzo Sabatini. Unfinished at the time of Vasari's death, it was completed by Federico Zuccari.

Aside from his career as a painter, Vasari was successful as an architect.[12] His loggia of the Palazzo degli Uffizi by the Arno opens up the vista at the far end of its long narrow courtyard. It is a unique piece of urban planning that functions as a public piazza, and which, if considered as a short street, is unique as a Renaissance street with a unified architectural treatment.[clarification needed] The view of the Loggia from the Arno reveals that, with the Vasari Corridor, it is one of the very few structures lining the river that is open to the river and appears to embrace the riverside environment. [citation needed]

In Florence, Vasari also designed the long passage, now called Vasari Corridor, which connects the Uffizi with the Palazzo Pitti on the other side of the river. The corridor passes alongside the River Arno on an arcade, crosses the Ponte Vecchio, and winds around the exterior of several buildings. It was once the location of the Mercado de Vecchio.[13]

He renovated the medieval churches of Santa Maria Novella and Santa Croce. In both buildings, he removed the original rood screen and loft, and remodeled the retro-choirs in the Mannerist taste of his time.[8]

In Santa Croce, he produced the painting of The Adoration of the Magi commissioned by Pope Pius V in 1566 and completed in February 1567. It was restored recently, before being exhibited in 2011 in Rome and Naples. Eventually, it will be returned to the church of Santa Croce in Bosco Marengo (Province of Alessandria, Piedmont). [citation needed]

In 1562, Vasari built the octagonal dome on the Basilica of Our Lady of HumilityinPistoia, an important example of High Renaissance architecture.[14]

In Rome, Vasari worked with Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola and Bartolomeo AmmannatiatPope Julius III's Villa Giulia.

Often called "the first art historian",[15] Vasari invented the genre of the encyclopedia of artistic biographies with his Le Vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori, ed architettori (Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects). This work was first published in 1550 and dedicated to Grand Duke Cosimo I de' Medici. Vasari introduced the term "Rinascita" (rebirth in Italian) in printed works – although an awareness of an ongoing "rebirth" in the arts had been in the air since the time of Alberti. Vasari's term, applied to the change in artistic styles with the work of Giotto, eventually would become the French term Renaissance (rebirth) widely applied to the era that followed. Vasari was responsible for the modern use of the term Gothic art, as well, although he only used the word Goth in association with the German style that preceded the rebirth, which he identified as "barbaric".

The Lives also included a novel treatise on the technical methods employed in the arts.[16][8] The book was partly rewritten and extended in 1568,[8] with the addition of woodcut portraits of artists (some conjectural).[citation needed]

The work shows a consistent and notorious bias in favour of Florentines and tends to attribute to them all the developments in Renaissance art – for example, the invention of engraving. Venetian art in particular (along with arts from other parts of Europe), is ignored systematically in the first edition. Between his first and second editions, Vasari visited Venice and while the second edition gave more attention to Venetian art (finally including Titian), it did so without achieving a neutral point of view. [citation needed]

Many inaccuracies exist within his Lives. For example, Vasari writes that Andrea del Castagno killed Domenico Veneziano, which is incorrect; Andrea died several years before Domenico. In another example, Vasari's biography of Giovanni Antonio Bazzi, whom he calls "Il Sodoma", published only in the second edition of the Lives (1568) after Bazzi's death, condemns the artist as being immoral, bestial, and vain. Vasari dismisses Bazzi's work as lazy and offensive, despite the artist's having been named a Cavalier of the Supreme Order of ChristbyPope Leo X and having received important commissions for the Villa Farnese and other sites.[17]

Vasari's biographies are interspersed with amusing gossip. Many of his anecdotes seem plausible, while others are assumed fictions, such as the tale of young Giotto painting a fly on the surface of a painting by Cimabue that supposedly, the older master repeatedly tried to brush away (a genre tale that echoes anecdotes told of the Greek painter Apelles). He did carry out research archives for exact dates, as modern art historians do, and his biographies are considered more reliable in the case of his contemporary painters and those of the preceding generation. Modern criticism – with new materials produced by research – has revised many of his dates and facts.[8]

Vasari included a short autobiography at the end of the Lives, and added further details about himself and his family in his lives of Lazzaro Vasari and Francesco Salviati.[8]

According to the historian Richard Goldthwaite,[18] Vasari was one of the earliest authors to use the term "competition" (or "concorrenza" in Italian) in its economic sense. He used it repeatedly, and stressed the concept in his introduction to the life of Pietro Perugino, in explaining the reasons for Florentine artistic preeminence. In Vasari's view, Florentine artists excelled because they were hungry, and they were hungry because their fierce competition amongst themselves for commissions kept them so. Competition, he said, is "one of the nourishments that maintain them".[citation needed]

References

Sources

Copies of Vasari's Lives of the Artists online:

|

| |

|---|---|

| Paintings |

|

| Frescoes |

|

| Buildings and structures |

|

| Books |

|

| Museums |

|

| Related |

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| People |

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Buildings |

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Patronage |

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Heraldry |

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Institutions |

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Art |

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Related |

| |||||||||||||||||||

| International |

|

|---|---|

| National |

|

| Academics |

|

| Artists |

|

| People |

|

| Other |

|