This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please help improve this articlebyintroducing citations to additional sources.

Find sources: "Huichang persecution of Buddhism" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2019) |

| Huichang persecution of Buddhism | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 會昌毀佛 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 会昌毁佛 | ||||||

| |||||||

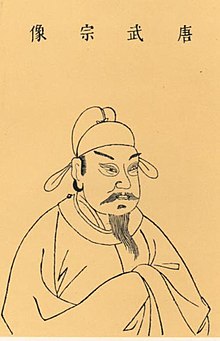

The Huichang Persecution of Buddhism (Chinese: 会昌毁佛) was initiated by Emperor Wuzong (Li Chan) of the Tang dynasty during the Huichang era (841–845). Among its purposes was to appropriate war funds and to cleanse Tang China of foreign influences. As such, the persecution was directed not only towards Buddhism but also towards other religions, such as Zoroastrianism, Nestorian Christianity, and Manicheism.

Emperor Wuzong's economic, social, and religious reasons for persecuting Buddhist organizations and temples throughout China were as follows:

An imperial edict of 845 stated the case against Buddhism as follows:

Buddhist monasteries daily grew higher. Men’s strength was used up in work with plaster and wood. Men’s gain was taken up in ornaments of gold and precious stones. Imperial and family relationships were forsaken for obedience to the fees of the priests. The marital relationship was opposed by the ascetic restraints. Destructive of law, injurious to mankind, nothing is worse than this way. Moreover, if one man does not plow, others feel hunger; if one woman does not tend the silkworms, others go cold. Now, in the Empire, there are monks and nuns innumerable. All depend on others to plow that they may eat, on others to raise silk that they may be clad. Monasteries and refuges (homes of ascetics) are beyond compute.

Beautifully ornamented; they take for themselves palaces as a dwelling.... We will repress this long-standing pestilence to its roots ... In all the Empire, more than four-thousand six-hundred monasteries are destroyed, two-hundred and sixty-thousand five-hundred monks and nuns are returning to the world, both (men and women) to be received as taxpaying householders. Refuges and hermitages which are destroyed number more than forty-thousand. We are resuming fertile land of the first grade, several tens of millions of Ch’ing (1 ching is 15.13 acres). We are receiving back as tax paying householders, male and female, one hundred and fifty thousand serfs. The aliens who hold jurisdiction over the monks and nuns show clearly that this is a foreign religion.

Ta Ch’in (Syrian) and Muh-hu-fo (Zoroastrian) monks to the number of more than three-thousand are compelled to return to the world, lest they confuse the customs of China. With simplified and regulated government, we will achieve a unification of our manners, that in future, all our youth may together return to the royal culture. We are now beginning this reformation; how long it will take we do not know.[4]

The first phase of the persecution was aimed at purifying or reforming the Buddhist establishment, rather than putting an end to it. Thus, the persecution began in 842 with an imperial edict declaring that undesirables such as sorcerers or convicts be separated out from the ranks of the Buddhist monks and nuns, and returned to lay life. In addition, monks and nuns were to turn their wealth over to the government; those who wished to keep their wealth would be returned to lay life and forced to pay taxes.[5] During this first phase, Confucian arguments for the reform of Buddhist institutions and the protection of society from Buddhist influence and practices were predominant.[6]

Gradually, however, the Emperor Wuzong became more and more impressed with the claims of some Taoists, and came to develop a severe dislike for Buddhism.[7] The Japanese monk Ennin, who lived in China during the persecution, even suggested that the emperor had been influenced by his illicit love of a beautiful Taoist princess.[8] As time went on, the emperor became more irascible and erratic in his judgments. One of his edicts banned the use of single-wheeled wheelbarrows, as they break up "the middle of the road," an important concept of Taoism.[9]

In 844, the persecution moved into a second phase, aimed at removing Buddhism altogether, rather than the reformation of Buddhism.[10] According to a report prepared by the Board of Worship, at the time there were 4,600 monasteries, 40,000 hermitages, and 260,500 monks and nuns. The emperor issued edicts that Buddhist temples and shrines be destroyed, that all monks (desirables as well as undesirables) be defrocked, that the properties of the monasteries be confiscated, and that Buddhist paraphernalia be destroyed.[11] By the edict of AD 845, all of the monasteries were abolished, with very few exceptions, with all images of bronze, silver, or gold handed over to the government.

In 846, the Emperor Wuzong died, perhaps on account of the elixirs of life he had been consuming (although it is also possible that he was intentionally poisoned). Shortly after his death, his successor proclaimed a general amnesty, ending the persecution.[12]

In addition to Buddhism, Wuzong persecuted other foreign religions as well. He all but destroyed Zoroastrianism and Manicheism in China, and his persecution of the growing Nestorian Christian churches sent Chinese Christianity into a decline, from which it did not recover until the establishment of the Yuan dynasty.

It most likely led to the disappearance of Zoroastrianism in China.[13]

Chinese records state Zoroastrianism and Christianity were regarded as heretical forms of Buddhism, and were included within the scope of the edicts. Below is from an edict concerning the two religions:

As for the Tai-Ch’in (Syrian) and Muh-hu (Zoroastrian) forms of worship, since Buddhism has already been cast out, these heresies alone must not be allowed to survive. People belonging to these also are to be compelled to return to the world, belong again to their own districts, and become taxpayers. As for foreigners, let them be returned to their own countries, there to suffer restraint.[14]

Islam was brought to China during the Tang dynastybyArab traders but had never had much influence outside of Arab traders. It is thought that this low profile was the reason that the 845 anti-Buddhist edict spared Islam.[15]

In7= 789 the Khalifa Harun al Raschid dispatched a mission to China, and there had been one or two less important missions in the seventh and eighth centuries; but from 879, the date of the Canton massacre, for more than three centuries to follow, we hear nothing of the Mahometans and their religion. They were not mentioned in the edict of 845, which proved such a blow to Buddhism and Nestorian Christianity – perhaps because they were less obtrusive in the propagation of their religion, a policy aided by the absence of anything like a commercial spirit in religious matters.

|

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Context and origin |

| |||||||||

| Tang dynasty |

| |||||||||

| Yuan dynasty |

| |||||||||

| By region |

| |||||||||

| Related modern people |

| |||||||||